FINANCING REGIONAL RAIL TRANSIT WITHOUT RAISING TAXES April 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mill Creek Watershed Scenario Project Report

Comprehensive Planning Workshop Spring 2010 Niehoff Urban Studio 2008-2010 Mill Creek Watershed Scenario Project Spring 2010 Executive Summary This report is a collective presentation of the studio process undertaken by the University of Cincinnati’s School of Planning 2010 Spring Comprehensive Workshop. The focus of the workshop was the Mill Creek Watershed, a 166 square mile area in southwestern Ohio. The Watershed has reached a critical state due to a multitude of both internal and external factors including industrial flight, environmental degradation, building vacancies, unemployment, auto dependence, and a worsening national economy. While numerous organizations construct and implement plans for the future of the Watershed, a lack of regional collaboration often results in little progress. Over the past century, the Mill Creek brought industry and increased population to the Watershed area. Today, the Mill Creek still remains a valuable natural asset. Urbanization has taken its toll, however, and both water quality and riparian corridor health have suffered. Another area of concern is the loss of population in the City of Cincinnati, and corresponding redistribution to the suburbs. Limited transportation options have worsened this outmigration by encouraging auto dependence. Social and environmental justice issues coincide with declining economic and environmental conditions in the Mill Creek Watershed. Due to its uncertain future, planning in the Mill Creek Watershed requires the consideration of multiple possibilities for how the area will transform. This Workshop used the scenario planning approach to establish four plausible outcomes for the Watershed. Scenario planning seeks to open discussions about how things may unfold, providing the opportunity for individuals and organizations to look beyond their individual plans and concerns for the future. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction......................................................................................................................1 1.0 Project Approach .......................................................................................................3 2.0 Recommendations.....................................................................................................5 3.0 Status of Corridor Study Recommendations..............................................................6 Light Rail Corridors ......................................................................................................7 Streetcar Service........................................................................................................18 Commuter Rail Corridors ...........................................................................................22 4.0 Alignment Details and Station Locations .................................................................28 Capital Cost Estimates...............................................................................................28 Operations and Maintenance Cost Estimates ............................................................29 Light Rail Alignments .................................................................................................30 Streetcar ....................................................................................................................46 Commuter Rail ...........................................................................................................50 -

La Metropole En Reference

LA METROPOLE EN REFERENCE Patrice Godier, Thierry Oblet, Guy Tapie 1 INTRODUCTION Patrice Godier, Thierry Oblet LA METROPOLE MOBILE Une fabrique de la conscience métropolitaine : la politique des transports urbains. Thierry Oblet Brève histoire de l'offre des transports urbains sur bordeaux Les axes d’un système de mobilité durable à l’échelle de la métropole bordelaise Les compromis d’un système de mobilité durable à l’échelle de la métropole bordelaise Conclusion Bordeaux métropole en gares : les promesses de l'intermodalité Patrice Godier L’intégration opérationnelle : sites et situations d’intermodalité L’intégration territoriale : les quartiers de gare L’intégration cognitive et servicielle : pratiques des flux et pratiques des lieux Des signaux faibles de la conscience métropolitaine LA METROPOLE CREATIVE Economie de la connaissance, économie créative et stratégies urbaines bordelaises : Guy Tapie Territoires Classe créative Politiques publiques Conclusion Projets créatifs et dynamiques métropolitaines : Darwin et Terres-Neuves :Guy Tapie Terres – Neuves, l’image et la tribu Du projet Darwin à l’éco-système de la caserne Niel Conclusion LA METROPOLE EN PERSPECTIVE 2 Bordeaux ou la possibilité d'une métropole campagne ? Carole Pourchez(Propos recueillis par Patrice Godier et Thierry Oblet) Vers une métropolisation participative ? Evolutions engagées et courants contrairesAurélie Couture L’inflexion du système communautaire Pour une métropolisation maitrisée Conclusion Cultures de la mobilité : leçons d'une comparaison, Cincinnati -

6.0 Public Involvement and Agency

Cincinnati Streetcar Project Environmental Assessment 6.0 PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT AND AGENCY COORDINATION Public outreach activities for the Cincinnati Streetcar project have occurred through the project website, mailings, news articles, meetings and presentations with stakeholders and citizens since 2007. A public involvement program for the Cincinnati Streetcar project was initiated for the Cincinnati Streetcar Feasibility Study (July 2007). The City of Cincinnati will continue to develop and implement this program throughout all phases of the project to keep citizens informed and engaged in the streetcar project. 6.1 Videos and Website The City of Cincinnati developed a video of the proposed modern streetcar, which was distributed throughout the community and posted on www.youtube.com. The City also developed an enhanced streetcar website found at www.cincinnati-oh.gov. This website contains a wide range of information about the streetcar and its benefits to Cincinnati and the region. The website is updated to reflect the latest information associated with the project. 6.2 Mailings The City of Cincinnati distributes project information through mass mailings to citizens within the study area. In February 2011, approximately 6,000 postcards were mailed to citizens and businesses within a three block radius of the streetcar route. This postcard promoted the benefits of the streetcar and provided an opportunity for citizens to sign up for project updates and construction news. 6.3 Community Briefings and Presentations The following is a list -

Affordable Housing

2015 - 2019 Consolidated Plan 2015 Action Plan Hamilton County Consolidated Plan Consolidated Plan Section Page Number Executive Summary ES-05 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 The Process PR-05 Lead & Responsible Agencies ......................................................................................................... .4 PR-10 Consultation ................................................................................................................................... .5 PR-15 Citizen Participation ...................................................................................................................... 23 Needs Assessment NA-05 Overview ....................................................................................................................................... 27 NA-10 Housing Needs Assessment .......................................................................................................... 28 NA-15 Disproportionately Greater Need: Housing Problems .................................................................. 38 NA-20 Disproportionately Greater Need: Severe Housing Problems ...................................................... 44 NA-25 Disproportionately Greater Need: Housing Cost Burdens ............................................................ 50 NA-30 Disproportionately Greater Need: Discussion .............................................................................. 51 NA-35 -

Climate Protection Action Plan: the Green Cincinnati Plan

CITY OF CINCINNATI CLIMATE PROTECTION ACTION PLAN The Green Cincinnati Plan June 19, 2008 (Version 4.0) Office of Environmental Quality Two Centennial Plaza 805 Central Avenue, Suite 320 Cincinnati, OH 45202 Phone (513) 352-6991 http://www.cincinnati-oh.gov/cmgr/pages/-17659-/ June 19, 2008 (V 4.0) Climate Protection Action Plan Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................... 1-3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4-9 Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 10-13 Cincinnati’s Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions Inventory............................................... 14-17 Cincinnati’s Emission Reduction Goals ............................................................................... 18-19 Emissions Reduction Measures ............................................................................................ 20-23 Transportation Task Team Recommendations ................................................................. 24-25 Energy Task Team Recommendations ............................................................................. 26-29 Waste Task Team Recommendations ................................................................................ 30-31 Land Use Task Team Recommendations ......................................................................... -

Section 3.0 Alternatives

Cincinnati Streetcar Project Environmental Assessment 3.0 ALTERNATIVES The Cincinnati Streetcar project would involve the construction and operation of a modern streetcar system and a maintenance and storage facility. This section describes the alternatives under consideration and explains how the two Build Alternatives are the result of coordination and integration of various transportation projects and studies over a span of 12 years. This section also conceptually describes the trackway, stations, vehicles, traction power substations, and maintenance and storage facility. The two Build Alternatives have been developed to a level of detail to enable a reasonable comparison of each alternative. For comparative purposes, a No Build Alternative is also evaluated. Based on the analysis presented in this Environmental Assessment, Build Alternative 1 is the recommended preferred alternative. 3.1 No Build Alternative The No Build Alternative is retained as a baseline for evaluation of the Build Alternatives. It includes existing and programmed improvements in the Ohio Kentucky Indiana Regional Council of Governments (OKI), Fiscal Year 2008-2011 Transportation Improvement Plan (TIP) for transit and roadways in the Cincinnati Streetcar project study area, specifically Freedom Way and additional roads, sidewalks, signals and lighting within The Banks street grid project. 3.2 Build Alternatives 3.2.1 Alternatives from Previous Studies Many transit alternatives have been considered for the study area, as part of regional studies and central core-focused studies dating back to 1998 (Appendix A). In addition to highway improvements, improved bus service, light rail transit, and a circulator for the central area of Cincinnati have been studied and proposed. Several of the transportation infrastructure projects over the past 12 years made recommendations for a light rail and/or streetcar system to be utilized in the City of Cincinnati’s core area. -

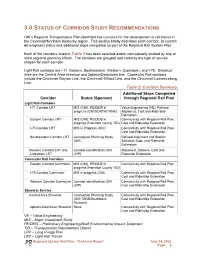

3.0 Status of Corridor Study Recommendations

3.0 STATUS OF CORRIDOR STUDY RECOMMENDATIONS OKI’s Regional Transportation Plan identified five corridors for the development of rail transit in the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky region. This section briefly describes each corridor, its current development status and additional steps completed as part of the Regional Rail System Plan. Each of the corridors listed in Table 2 has been selected and/or conceptually studied by one or more regional planning efforts. The corridors are grouped and listed by the type of service chosen for each corridor: Light Rail corridors are I-71, Eastern, Southeastern, Western, Crosstown, and I-75. Streetcar lines are the Central Area streetcar and Uptown/Downtown line. Commuter Rail corridors include the Cincinnati-Dayton Line, the Cincinnati-Milford Line, and the Cincinnati-Lawrenceburg Line. Table 2: Corridor Summary Additional Steps Completed Corridor Status (Sponsor) through Regional Rail Plan Light Rail Corridors I-71 Corridor LRT MIS (OKI), PE/DEIS in Value Engineering (VE), Refined progress (OKI/SORTA/TANK) Alignment, Cost and Ridership Estimation Eastern Corridor LRT MIS (OKI), PE/DEIS in Connectivity with Regional Rail Plan, progress (Hamilton County TID) Cost and Ridership Estimation I-75 Corridor LRT MIS in Progress (OKI) Connectivity with Regional Rail Plan, Cost and Ridership Estimation Southeastern Corridor LRT Conceptual Planning Study Refined Alignment and Station (OKI) Selection Cost, and Ridership Estimation Western Corridor LRT and Corridor Identification (OKI Alignment, Stations, Cost and -

Over-The-Rhine Community Housing

Over-the-Rhine C o m p r e h e n s i v e P l a n June 2002 The Over-the-Rhine Comprehensive Plan A consensus-based plan by people who care Mayor Charlie Luken Prepared for the Over-the-Rhine Community Valerie A. Lemmie, City Manager Prepared by the City of Cincinnati City Planning Department in collaboration with City Council Minette Cooper OTR Community Council David Crowley OTR Coalition Paul Booth ABCD Resident’s Table John Cranley Other Community Stakeholders Pat DeWine Chris Monzel City of Cincinnati David Pepper Department of Community Development Alicia Reece Department of Transportation and Engineering James Tarbell Cincinnati Recreation Commission Cincinnati Park Board Division of Employment and Training Design consulting by Kenneth Cunningham and Associates, Inc. in association with the University of Cin- cinnati Community Design Center and Olika Design Table of Contents Credits iii Executive Summary 1 Introduction 19 Existing Conditions 25 Housing 35 Economic Development 65 Safety 87 Transportation 99 Quality of Life 119 Implementation 145 Appendix A: The Community Design Process 171 Appendix B: List of Demographics 235 Appendix C: Buildings on the National Register 237 Appendix D: Social Service Organizations 239 Appendix E: Financing for Housing Development 243 i ii Credits Planning Steering Committee Linda Brock, ABCD Resident Jim Moll, OTR Coalition Mary Burke,OTR Housing Network Bonnie Neumeier, OTR Community Council Pat Clifford, Drop Inn Center Judith Osborn, OTR Chamber of Commerce, Business Representative Vanteen Coates, St. Mary Baptist Church, OTR Coalition Walter Reinhaus, At Large Resident Elaine Coffy-Vinson, ABCD Resident Al Rohs, Rohs Hardware, Business Representative Darrick Dansby, Smart Money, Dave Rohs, Rohs Hardware, Business Representative Wade Dent, The Electronic Ark, Stephen Rohs, Business Representative Chuck Downton, OTR Coalition Marva Royal, ABCD Resident Tom Dutton, OTR Housing Network Kathy Schwab, Downtown Cincinnati Inc. -

Proposal of Alternate Route to Mount Auburn Tunnel in Cincinnati by Light Rail

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________October 8, 2007 I, _________________________________________________________,Bhoomi Vala hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master in Community Planning in: It is entitled: Proposal of Alternate Route to Mount Auburn Tunnel in Cincinnati by Light Rail This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________Dr. Xinhao Wang _______________________________Dr. Carla Chifos _______________________________Prof. John Niehaus _______________________________ _______________________________ Proposal of Alternate Route to Mount Auburn Tunnel in Cincinnati by Light Rail PROPOSAL OF ALTERNATE ROUTE TO MOUNT AUBURN TUNNEL IN CINCINNATI BY LIGHT RAIL A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER IN COMMUNITY PLANNING School of Planning College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning 2008 By: Bhoomi Vala B. Arch, Maharaja Sayajirao University, India, 2004 Thesis Committee Chair: Dr. Xinhao Wang Faculty: Dr. Carla Chifos Reader: Prof. John Niehaus ii Bhoomi Vala Proposal of Alternate Route to Mount Auburn Tunnel in Cincinnati by Light Rail ABSTRACT In November 1993, the Ohio-Kentucky-Indiana Council of Governments (OKI) proposed light rail in Cincinnati along the six corridors namely I-71, I – 75, Westside alignment along I – 74, Eastside alignment, I – 471, and Crosstown route. Of the six corridors the I-71light rail corridor was identified as the highest priority transportation corridor and was planned to connect Florence in Kentucky to Kings Mill in Cincinnati, Ohio. The starter segment of the I-71 light rail corridor was planned to connect the Downtown Covington in Kentucky to Blue Ash in Cincinnati. As the Downtown of Cincinnati and the University of Cincinnati in Uptown are the major employment centers of Cincinnati, the connection of Uptown to Downtown was planned as a part of the I-71 Corridor light rail. -

TANK Transit Network Study FINAL

TRANSIT NETWORK STUDY | FINAL Transit Authority of Northern Kentucky TANK Transit Network Study FINAL December 2013 TRANSIT NETWORK STUDY | FINAL Transit Authority of Northern Kentucky Table of Contents Page 1 Executive Summary .........................................................................................................1-1 2 Existing Transit Services ..................................................................................................2-1 System Overview ................................................................................................................................... 2-1 Frequency and Span ............................................................................................................................. 2-4 Historical Trends ..................................................................................................................................... 2-7 Productivity Measures ........................................................................................................................... 2-8 3 Document Review ............................................................................................................3-1 TANK Documents .................................................................................................................................... 3-1 External Documents................................................................................................................................ 3-2 4 Land Use and Demographic Characteristics .....................................................................4-1 -

Section 2.0 Study Area Characteristics

Cincinnati Streetcar Project Environmental Assessment 2.0 STUDY AREA CHARACTERISTICS This chapter describes the characteristics of the populations, neighborhoods, employment centers, activity centers, and transportation facilities and services within the project study area. A discussion of the project’s consistency with local transportation plans developed for the City of Cincinnati, Southwest Ohio Regional Transit Agency (SORTA), and regional entities is also discussed in this chapter. The Cincinnati Streetcar is designed to serve the core of the urban region, which includes the Downtown, Over-the-Rhine (OTR), and Uptown neighborhoods of Cincinnati (Figure 1). These three areas, which are immediately adjacent to one another, comprise the largest and most densely developed employment and activity center in the Greater Cincinnati region. The street network that connects the three areas is constrained by traffic and a significant change in elevation between Downtown and OTR and the Uptown area. Downtown and OTR sit in the basin and are just north of the Ohio River. Uptown’s elevation is a few hundred feet higher. Although interstate highways bracket Downtown and Uptown, they do not allow for connectivity between the three areas. A street grid exists on Downtown and OTR but the street patterns in Uptown are less regular, and feature several “superblocks.” All three areas include sidewalks and are pedestrian-oriented. 2.1 Demographics 2.1.1 Existing Population The study area is a relatively narrow corridor within the larger Downtown, OTR and Uptown areas. The population within the project study area corridor was estimated to be 4,169 in 2009 (Claritas Inc., 2009). This is approximately one percent of the population of the City of Cincinnati, with a population of 331,285.