Roleplaying,” June 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONJECTURE GAMES PRESENTS: Conjectural Roleplaying Gamemaster

CONJECTURE GAMES PRESENTS: CRGE conjectural roleplaying gamemaster emulator By Zach Best Artwork by Matthew Vasey The Helldragon (order #6976544) “If everyone is thinking alike, then somebody isn’t thinking.” – George S. Patton Dedicated to Katie. Who shares every step with me. Written by Zach Best Artwork by Matthew Vasey Published by Conjecture Games (www.conjecturegames.com) Special Thanks to Alex Yari, Francis Flammang, David Dankel, Nicky Tsouklais, Matthew Mooney, Aaron Zeitler, Kenny Norris, Jimmy Williams, and Deathworks for playtesting, editing, and general commenting. Very Special Thanks to Chris Stieha for being the first and most thorough playtester an indie game designer could ever ask for. All text is © Zach Best (2014). All artwork is © Matthew Vasey (2014) and used with permission for this work. The mention of or reference to any company or product in these pages is not a challenge to the trademark or copyright concerned. 2 The Helldragon (order #6976544) Table of Contents What is CRGE? pg. 4 Loom of Fate – Binary GM Emulator, pg. 6 The Surge Count, pg. 8 Unexpectedly Explanations, pg. 10 Loom of Fate Examples, pg. 11 Loom of Fate Tutorial, pg. 13 Conjured Threads – Story Indexing Game Engine, pg. 14 Stage of the Scene, pg. 16 CRGE Scene Setup, pg. 18 Bookkeeping, pg. 18 Storyspinning – Frameworks for CRGE, pg. 20 Vignette Framework, pg. 21 Vignette Framework Tutorial, pg. 23 Tapestry –Multiplayer CRGE Module, pg. 24 Appendix I (Tables), pg. 27 Appendix II (Vignette Framework Tutorial Example), pg. 28 3 The Helldragon (order #6976544) What is CRGE? Conjecture The Conjectural Roleplaying Gamemaster “Is the door locked?” This is a very simple Emulator (“CRGE”) is a supplement for any pen question applicable to many RPG adventures. -

A Sense of Presence: Mediating an American Apocalypse

religions Article A Sense of Presence: Mediating an American Apocalypse Rachel Wagner Department of Philosophy and Religion, Ithaca College, Ithaca, NY 14850, USA; [email protected] Abstract: Here I build upon Robert Orsi’s work by arguing that we can see presence—and the longing for it—at work beyond the obvious spaces of religious practice. Presence, I propose, is alive and well in mediated apocalypticism, in the intense imagination of the future that preoccupies those who consume its narratives in film, games, and role plays. Presence is a way of bringing worlds beyond into tangible form, of touching them and letting them touch you. It is, in this sense, that Michael Hoelzl and Graham Ward observe the “re-emergence” of religion with a “new visibility” that is much more than “simple re-emergence of something that has been in decline in the past but is now manifesting itself once more.” I propose that the “new awareness of religion” they posit includes the mediated worlds that enchant and empower us via deeply immersive fandoms. Whereas religious institutions today may be suspicious of presence, it lives on in the thick of media fandoms and their material manifestations, especially those forms that make ultimate promises about the world to come. Keywords: apocalypticism; Orsi; enchantment; fandom; video games; pervasive games; cowboy; larp; West 1. Introduction Michael Hoelzl and Graham Ward observe the “re-emergence” of religion today with a “new visibility” that is “far more complex and nuanced than simple re-emergence of something that has been in decline in the past but is now manifesting itself once more” (Hoelzl and Ward 2008, p. -

Platf Orm Game First Person Shooter Strategy Game Alternatereality Game

First person shooter Platform game Alternate reality game Strategy game Platform game Strategy game The platform game (or platformer) is a video game genre Strategy video games is a video game genre that emphasizes characterized by requiring the player to jump to and from sus- skillful thinking and planning to achieve victory. They empha- pended platforms or over obstacles (jumping puzzles). It must size strategic, tactical, and sometimes logistical challenges. be possible to control these jumps and to fall from platforms Many games also offer economic challenges and exploration. or miss jumps. The most common unifying element to these These games sometimes incorporate physical challenges, but games is a jump button; other jump mechanics include swing- such challenges can annoy strategically minded players. They ing from extendable arms, as in Ristar or Bionic Commando, are generally categorized into four sub-types, depending on or bouncing from springboards or trampolines, as in Alpha whether the game is turn-based or real-time, and whether Waves. These mechanics, even in the context of other genres, the game focuses on strategy or tactics. are commonly called platforming, a verbification of platform. Games where jumping is automated completely, such as The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, fall outside of the genre. The platform game (or platformer) is a video game genre characterized by requiring the player to jump to and from sus- pended platforms or over obstacles (jumping puzzles). It must be possible to control these jumps and to fall from platforms or miss jumps. The most common unifying element to these games is a jump button; other jump mechanics include swing- ing from extendable arms, as in Ristar or Bionic Commando, or bouncing from springboards or trampolines, as in Alpha Waves. -

The No-Prep Gamemaster Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Random Tables

The No-Prep Gamemaster Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Random Tables Sample file Matt Davids 1 Edited By Ryan Thompson Layout & Design By Matt Davids Patrons Scott Frega, Heath Baxter & Andrew Nagy Thanks Mik Calow, Jeff Gatlin & JE Melton Published by dicegeks. Contents copyright © 2019 dicegeeks and Matt Davids. All rights reserved. Some artwork © 2015 Dean Spencer, used with permission. All rights reserved. SampleCover image from iStock. Used under license. file www.dicegeeks.com 2 Get Free Dungeon Maps and More dicegeeks.com/free Sample file 3 Table of Contents Glossary........................................................................5 Introduction.................................................................6 ARCANA Gamemaster Evolution................................................8 True Role of the GM....................................................11 The No‐Prep Approach...............................................18 THREE KEYS Fill Yourself with Stories..............................................21 Don't Set Dungeons in Stone......................................31 Random Tables...........................................................35 ARROWS IN THE QUIVER Best Case/Worse Case.................................................45 Don't Create Everything.............................................48 List of Names..............................................................51 Listen to the Table......................................................54 Players Can Help Create..............................................57 -

Mud Connector

Archive-name: mudlist.doc /_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/ /_/_/_/_/ THE /_/_/_/_/ /_/_/ MUD CONNECTOR /_/_/ /_/_/_/_/ MUD LIST /_/_/_/_/ /_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/ o=======================================================================o The Mud Connector is (c) copyright (1994 - 96) by Andrew Cowan, an associate of GlobalMedia Design Inc. This mudlist may be reprinted as long as 1) it appears in its entirety, you may not strip out bits and pieces 2) the entire header appears with the list intact. Many thanks go out to the mud administrators who helped to make this list possible, without them there is little chance this list would exist! o=======================================================================o This list is presented strictly in alphabetical order. Each mud listing contains: The mud name, The code base used, the telnet address of the mud (unless circumstances prevent this), the homepage url (if a homepage exists) and a description submitted by a member of the mud's administration or a person approved to make the submission. All listings derived from the Mud Connector WWW site http://www.mudconnect.com/ You can contact the Mud Connector staff at [email protected]. [NOTE: This list was computer-generated, Please report bugs/typos] o=======================================================================o Last Updated: June 8th, 1997 TOTAL MUDS LISTED: 808 o=======================================================================o o=======================================================================o Muds Beginning With: A o=======================================================================o Mud : Aacena: The Fatal Promise Code Base : Envy 2.0 Telnet : mud.usacomputers.com 6969 [204.215.32.27] WWW : None Description : Aacena: The Fatal Promise: Come here if you like: Clan Wars, PKilling, Role Playing, Friendly but Fair Imms, in depth quests, Colour, Multiclassing*, Original Areas*, Tweaked up code, and MORE! *On the way in The Fatal Promise is a small mud but is growing in size and player base. -

Mathematics and Role-Playing Games

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences Faculty/Staff Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences 2012 Coming Out of the Dungeon: Mathematics and Role-Playing Games Kris H. Green St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub Part of the Mathematics Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Publication Information Green, Kris H. (2012). "Coming Out of the Dungeon: Mathematics and Role-Playing Games." Mathematics in Popular Culture: Essays on Appearances in Film, Fiction, Games, Television and Other Media , 99-113. Please note that the Publication Information provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub/19 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Coming Out of the Dungeon: Mathematics and Role-Playing Games Abstract After hiding it for many years, I have a confession to make. Throughout middle school and high school my friends and I would gather almost every weekend, spending hours using numbers, probability, and optimization to build models that we could use to simulate almost anything. That’s right. My big secret is simple. I was a high school mathematical modeler. Of course, our weekend mathematical models didn’t bear any direct relationship to the models we explored in our mathematics and science classes. -

Mu's Unbelievably Long and Disjointed Ramblings About RPG Design

Mu's Unbelievably Long and Disjointed Ramblings About RPG Design Mu's Unbelievably Long and Disjointed Ramblings About RPG Design 1 / 101 Copyright 2001-Now by Howard Collins . Mu's Unbelievably Long and Disjointed Ramblings About RPG Design 1 Foreword .........................................................................................................................................6 2 General Topics ................................................................................................................................7 2.1 Holistic Game Design .............................................................................................................7 2.2 The Grandfather Clause of Stupidity ......................................................................................8 2.3 Paths Unlimited ......................................................................................................................9 2.4 Design from Tech or Tech from Design ...............................................................................10 2.5 Roleplaying = Fighting..........................................................................................................11 2.6 Limiting Player Power...........................................................................................................13 2.7 Segregating Player Power....................................................................................................15 2.8 The No Numbers Concept....................................................................................................16 -

Definitions of “Role-Playing Games”

This is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Routledge in Role- Playing Game Studies: Transmedia Foundations on April 4, 2018, available online: https://www.routledge.com/Role-Playing-Game-Studies-Transmedia-Foundations/Deterding-Zagal/p/book/9781138638907 Please cite as: Zagal, José P. and Deterding, S. (2018). Definitions of “Role-Playing Games”. In Zagal, José P. and Deterding, S. (eds.), Role-Playing Game Studies: Transmedia Foundations. New York: Routledge, 19-51. 2 Definitions of “Role-Playing Games” José P. Zagal; Sebastian Deterding For some, defining “game” is a hopeless task (Parlett 1999). For others, the very idea that one could capture the meaning of a word in a list of defining features is flawed, because language and meaning-making do not work that way (Wittgenstein 1963). Still, we use the word “game” every day and, generally, understand each other when we do so. Among game scholars and professionals, we debate “game” definitions with fervor and sophistication. And yet, while we usually agree with some on some aspects, we never seem to agree with everyone on all. At most, we agree on what we disagree about – that is, what disagreements we consider important for understanding and defining “games” (Stenros 2014). What is true for “games” holds doubly for “role-playing games”. In fact, role- playing games (RPGs) are maybe the most contentious game phenomenon: the exception, the outlier, the not-quite-a-game game. In their foundational game studies text Rules of Play, Salen and Zimmerman (2004, 80) acknowledge that their definition of a game (“a system in which players engage in an artificial conflict, defined by rules, that results in a quantifiable outcome”) considers RPGs a borderline case. -

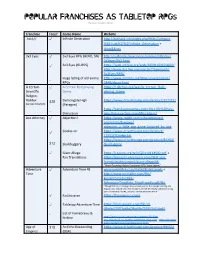

POPULAR FRANCHISES AS TABLETOP RPGS Revision 10 (Apr.2021)

POPULAR FRANCHISES AS TABLETOP RPGS Revision 10 (Apr.2021) Franchise Free? Game Name Website .hack// ✓ Infinite Generation http://dothack.info/index.php?title=Category %3A.hack%2F%2FInfinite_Generation + Odds&Ends 3x3 Eyes ✓ 3x3 Eyes RPG (HERO, SN) http://surbrook.devermore.com/worldbooks/ 3x3eyes/3x3.html ✓ 3x3 Eyes (GURPS) https://web.archive.org/web/20001109020600/ http://www.dca.fee.unicamp.br/~henriqmh/ 3x3Eyes/RPG/ Huge listing of old anime http://www.oocities.org/timessquare/arena/ - RPGs 2448/about.html A Certain ✓ A Certain Roleplaying https://1d4chan.org/wiki/A_Certain_Role- Scientific Game playing_Game Railgun, Raildex $20 Demongate High https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/127312/ See also Smallville. (Paragon) https://yarukizerogames.com/2011/02/10/role- - Discussion play-this-a-certain-scientific-railgun/ Ace Attorney ✓ Abjection! https://www.reddit.com/r/AceAttorney/ comments/8zwgwa/ abjection_a_little_rpg_game_inspired_by_ace ✓ Cookie Jar https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/ 115517/Cookie-Jar https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/84260/ $12 Skullduggery Skulduggery ✓ Giant Allege: https://i.4pcdn.org/tg/1520114144592.pdf + Fan Translations https://projects.inklesspen.com/fatal-and- friends/professorprof/giant-allege/#6 “Heart-Pounding Robot Courtroom RPG" from Japan!” Adventure ✓ Adventure Time 4E www.mediafire.com/?ia9628cdx6zacwb + Time http://www.mediafire.com/file/ kmxkml5mzduc994/ AdventureTimeBeta_PrintFriendly.pdf/file “Though I’m not releasing a new version just for this, people reading this original post should -

The Personality Module

The Personality Module How Can Personality Affect Agents In a Turn-Based Strategy Game? THESIS By Arild Johan Jensen and Håvard Nes Department of Information Science and Media Studies University of Bergen Spring 2008 I Acknowledgements Firstly and mostly we must thank Aleksander Krzywinski and Arne S. Helgesen for their excellent work on the Caeneus Agent and StateCraft and Weiqin Chen for her supervision and guidance. Secondly, we would like to thank all the testers for spending so much of their time with our game and in discussions with us. In addition to Arne, the testers were Ronny Simon Mo, Jarl Helge Utvik, Mannaf Haque, Espen Halvorsen and Dag Christian Weløy. Tomas H. Ekeli, who gave us the idea to use StateCraft as test environment also deserves our gratitude. Last, but not least, Arild Johan would like to thank his significant other, Hanne Beth Borge, for her support and patience. II Table of Contents Acknowledgements.............................................................................................................II Table of Contents.............................................................................................................. III List of figures..................................................................................................................... V List of tables...................................................................................................................... VI List of code excerpts ........................................................................................................VII -

The Tviews Table Role-Playing Game

Journal of Virtual Reality and Broadcasting, Volume 5(2008), no. 8 The TViews Table Role-Playing Game Ali Mazalek, Basil Mironer, Elijah O’Rear, Dana Van Devender Synaesthetic Media Lab, GVU Center Georgia Institute of Technology 85 5th Street NW, TSRB 209, Atlanta, GA 30332 +1 404 385 3179, email: [email protected] www: synlab.gatech.edu Abstract 1 Introduction The TViews Table Role-Playing Game (TTRPG) is People across all cultures and age groups engage in a digital tabletop role-playing game that runs on the different forms of gameplay and storytelling, in both TViews table, bridging the separate worlds of tradi- analog and digital form. As pastimes, games and sto- tional role-playing games with the growing area of rytelling offer various kinds of benefits, such as en- massively multiplayer online role-playing games. The tertainment, relaxation, skill building, and competitive TViews table is an interactive tabletop media platform challenges. Many games incorporate storytelling ele- that can track the location of multiple tagged objects in ments, and certain stories also unfold in a game-like real-time as they are moved around its surface, provid- form. ing a simultaneous and coincident graphical display. One form of storytelling gameplay that has gained In this paper we present the implementation of the first appeal since the 1970s are role-playing games, com- version of TTRPG, with a content set based on the tra- monly referred to as RPGs. In RPGs, the players take ditional Dungeons & Dragons rule-set. We also dis- on the roles of fictional characters that they themselves cuss the results of a user study that used TTRPG to have created, and work together to tell a story within explore the possible social context of digital tabletop a given system of rules. -

WEST END Ijlgames

WEST END u iJlGAMES GAMEMASTER HANDBOOK FOR SECOND EDITION Paul Daly Trautmann, Chuck Truett • Development and Editing: Bill Smith Graphics: Cathleen Hunter • Cover Art: Lucasfilm Ltd. Interior Art: Paul Daly, Mike Jackson, David Plunkett Publisher: Daniel Scott Palter • Associate Publisher/Treasurer: Denise Palter Associate Publisher/Sales Manager: Richard Hawran Senior Editor: Greg Farshtey • Editors: Bill Smith, Ed Stark • Art Director: Stephen Crane Graphic Artists: Cathleen Hunter, John Paul Lona • Sales Assistant: Bill Olmesdahl Licensing Manager: Ron Seiden • Warehouse Manager: Ed Hill V _____________________________ __________________________________/ Published by WXJWEST \ * ^ G A M E 5 RR 3 Box 2345 Honesdale PA 18431 40065 ® .,M and © 1993 Lucaslilm. Ltd. (LFL). All Rights Reserved. Trademarks of LFL used by West End Games under authorization. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction............................... Bill Smith- Beginning Adventures.......... Chuck Truett • The Star Wars Adventure..... Chuck Truett Settings.......v................... .......... Chuck TruettV y GaniemasteiyCharacters........-. Steven fd. Lorenz . V Encounters .................. Chuck Truett \ Equipment An d Artifacts....... Eric Trautmann Props........ t.... ...................... ...... \ \ S t $ v e n H. Lorenz Improvisation..... .................... Steven H. Lorenz / . \ ' Campaigns ....................... .......... • John Terra Tales of the Smoking Blaster Adventure by Bill Smith Star Wars Rules Questions .... 'The Star Wars Questionnaire __ STAR.