Reasons for Visiting Destinations Motives Are Not Motives for Visiting — Caveats and Questions for Destination Marketers Leonardo A.N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Decnet-Plusftam and Virtual Terminal Use and Management

VSI OpenVMS DECnet-Plus FTAM and Virtual Terminal Use and Management Document Number: DO-FTAMMG-01A Publication Date: June 2020 Revision Update Information: This is a new manual. Operating System and Version: VSI OpenVMS Integrity Version 8.4-2 VSI OpenVMS Alpha Version 8.4-2L1 VMS Software, Inc., (VSI) Bolton, Massachusetts, USA DECnet-PlusFTAM and Virtual Terminal Use and Management Copyright © 2020 VMS Software, Inc. (VSI), Bolton, Massachusetts, USA Legal Notice Confidential computer software. Valid license from VSI required for possession, use or copying. Consistent with FAR 12.211 and 12.212, Commercial Computer Software, Computer Software Documentation, and Technical Data for Commercial Items are licensed to the U.S. Government under vendor's standard commercial license. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. The only warranties for VSI products and services are set forth in the express warranty statements accompanying such products and services. Nothing herein should be construed as constituting an additional warranty. VSI shall not be liable for technical or editorial errors or omissions contained herein. HPE, HPE Integrity, HPE Alpha, and HPE Proliant are trademarks or registered trademarks of Hewlett Packard Enterprise. Intel, Itanium and IA-64 are trademarks or registered trademarks of Intel Corporation or its subsidiaries in the United States and other countries. UNIX is a registered trademark of The Open Group. The VSI OpenVMS documentation set is available on DVD. ii DECnet-PlusFTAM and Virtual -

Inter-Autonomous-System Routing: Border Gateway Protocol

Inter-Autonomous-System Routing: Border Gateway Protocol Antonio Carzaniga Faculty of Informatics University of Lugano May 18, 2010 © 2005–2007 Antonio Carzaniga 1 Outline Hierarchical routing BGP © 2005–2007 Antonio Carzaniga 2 Routing Goal: each router u must be able to compute, for each other router v, the next-hop neighbor x that is on the least-cost path from u to v v x3 x4 u x2 x1 © 2005–2007 Antonio Carzaniga 3 Network Model So far we have studied routing over a “flat” network model 14 g h j 4 1 1 2 3 9 d e f 1 2 1 1 1 3 4 a b c Also, our objective has been to find the least-cost paths between sources and destinations © 2005–2007 Antonio Carzaniga 4 More Realistic Topologies © 2005–2007 Antonio Carzaniga 5 Even More Realistic ©2001 Stephen Coast © 2005–2007 Antonio Carzaniga 6 An Internet Map ©1999 Lucent Technologies © 2005–2007 Antonio Carzaniga 7 Higher-Level Objectives Scalability ◮ hundreds of millions of hosts in today’s Internet ◮ transmitting routing information (e.g., LSAs) would be too expensive ◮ forwarding would also be too expensive Administrative autonomy ◮ one organization might want to run a distance-vector routing protocol, while another might want to run a link-state protocol ◮ an organization might not want to expose its internal network structure © 2005–2007 Antonio Carzaniga 8 Hierarchical Structure Today’s Internet is organized in autonomous systems (ASs) ◮ independent administrative domains Gateway routers connect an autonomous system with other autonomous systems An intra-autonomous system routing protocol runs within an autonomous system (e.g., OSPF) ◮ this protocol determines internal routes ◮ internal router ↔ internal router ◮ internal router ↔ gateway router ◮ gateway router ↔ gateway router © 2005–2007 Antonio Carzaniga 9 Hierarchical Structure 32 25 24 AS3 31 21 23 35 AS2 33 22 34 11 42 13 12 AS4 43 14 AS1 41 © 2005–2007 Antonio Carzaniga 10 Inter-AS Routing An inter-autonomous system routing protocol determines routing at the autonomous-system level AS3 AS2 AS4 AS1 At AS3: AS1 → AS1; AS2 → AS2; AS4 → AS1. -

Towards Coordinated, Network-Wide Traffic

Towards Coordinated, Network-Wide Traffic Monitoring for Early Detection of DDoS Flooding Attacks by Saman Taghavi Zargar B.Sc., Computer Engineering (Software Engineering), Azad University of Mashhad, 2004 M.Sc., Computer Engineering (Software Engineering), Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the School of Information Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2014 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF INFORMATION SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Saman Taghavi Zargar It was defended on June 3, 2014 and approved by James Joshi, Ph.D., Associate Professor, School of Information Sciences David Tipper, Ph.D., Associate Professor, School of Information Sciences Prashant Krishnamurthy, Ph.D., Associate Professor, School of Information Sciences Konstantinos Pelechrinis, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, School of Information Sciences Yi Qian, Ph.D., Associate Professor, College of Engineering, Dissertation Advisors: James Joshi, Ph.D., Associate Professor, School of Information Sciences, David Tipper, Ph.D., Associate Professor, School of Information Sciences ii Copyright c by Saman Taghavi Zargar 2014 iii Towards Coordinated, Network-Wide Traffic Monitoring for Early Detection of DDoS Flooding Attacks Saman Taghavi Zargar, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2014 DDoS flooding attacks are one of the biggest concerns for security professionals and they are typically explicit attempts to disrupt legitimate users' access to services. Developing a com- prehensive defense mechanism against such attacks requires a comprehensive understanding of the problem and the techniques that have been used thus far in preventing, detecting, and responding to various such attacks. In this thesis, we dig into the problem of DDoS flooding attacks from four directions: (1) We study the origin of these attacks, their variations, and various existing defense mecha- nisms against them. -

A Logical Approach to Representing and Reasoning About Interdomain Routing Policies

A Logical Approach to Representing and Reasoning About Interdomain Routing Policies Anduo Wang and Zhijia Chen Temple University Abstract. The Internet paths connecting independently operated networks, also called domains or autonomous systems (ASes), are driven by semantically rich policies: the interdomain routing protocol that computes the Internet paths allows the ASes to influence path selection with their local policies, such as economic concerns or operational constraints. An AS can promote a policy compliant but globally longer path by carefully tweaking lower level path attributes that are used in the routing protocol. Such operational policies are notoriously complex and hard to understand. This paper takes a step back and asks whether a more principled logical approach can lead to AS policies that are easier to under- stand, reuse, evolve, and coexist. To this end, we propose to represent policies by database integrity constraints, in the form of headless datalog rules about what are the acceptable Internet paths. The simple datalog expression unifies a wide spectrum of AS policies, ranging from classic examples seen in today’s routing practice to futuristic ones proposed in various extensions to Internet routing. More importantly, by leveraging datalog’s connection to the theorem proving technique called the residue method, we developed a new technique for understanding the interactions among the policies — whether a policy can inadvertly affect another, and how to resolve the conflict. We also evaluated our logical policies, show- ing promising result with small overhead for conflict resolution on realistic large networks. 1 Introduction The Internet today is more than connecting remote hosts with valid paths. -

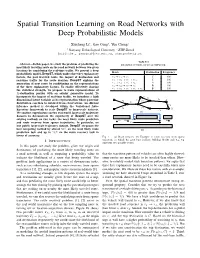

Spatial Transition Learning on Road Networks with Deep Probabilistic Models

Spatial Transition Learning on Road Networks with Deep Probabilistic Models Xiucheng Liy, Gao Congy, Yun Chengz y Nanyang Technological Univeristy, z ETH Zurich fxli055@e., [email protected], [email protected] TABLE I Abstract—In this paper, we study the problem of predicting the EXAMPLE OF TRIPS ON ROAD NETWORK. most likely traveling route on the road network between two given locations by considering the real-time traffic. We present a deep Route Destination Frequency probabilistic model–DeepST–which unifies three key explanatory factors, the past traveled route, the impact of destination and r3 ! r2 ! r4 C 400 real-time traffic for the route decision. DeepST explains the r3 ! r2 ! r5 ! r10 C 100 generation of next route by conditioning on the representations r1 ! r2 ! r5 ! r6 A 100 of the three explanatory factors. To enable effectively sharing r1 ! r2 ! r7 ! r8 B 100 r ! r ! r ! r ! r B 100 the statistical strength, we propose to learn representations of 1 2 5 6 9 K-destination proxies with an adjoint generative model. To incorporate the impact of real-time traffic, we introduce a high C r<latexit sha1_base64="(null)">(null)</latexit> 10 r<latexit sha1_base64="(null)">(null)</latexit> dimensional latent variable as its representation whose posterior r<latexit sha1_base64="(null)">(null)</latexit> 4 6 A r<latexit sha1_base64="lQIphb3ZxX5RFxPPJ2+0wE0HOKM=">AAAB6nicbZBNS8NAEIYn9avWr6hHL4tF8FQSEfRY9OKxov2ANpTNdtMu3WzC7kQooT/BiwdFvPqLvPlv3LY5aOsLCw/vzLAzb5hKYdDzvp3S2vrG5lZ5u7Kzu7d/4B4etUySacabLJGJ7oTUcCkUb6JAyTup5jQOJW+H49tZvf3EtRGJesRJyoOYDpWIBKNorQfd9/tu1at5c5FV8AuoQqFG3/3qDRKWxVwhk9SYru+lGORUo2CSTyu9zPCUsjEd8q5FRWNugny+6pScWWdAokTbp5DM3d8TOY2NmcSh7YwpjsxybWb+V+tmGF0HuVBphlyxxUdRJgkmZHY3GQjNGcqJBcq0sLsSNqKaMrTpVGwI/vLJq9C6qPmW7y+r9ZsijjKcwCmcgw9XUIc7aEATGAzhGV7hzZHOi/PufCxaS04xcwx/5Hz+AAKOjZo=</latexit> -

User Manual Workbench

User Manual Workbench Create and Customize User Interfaces for Router Control www.s-a-m.com WorkBench User Manual Issue1 Revision 5 Page 2 © 2017 SAM WorkBench User Manual Information and Notices Information and Notices Copyright and Disclaimer Copyright protection claimed includes all forms and matters of copyrightable material and information now allowed by statutory or judicial law or hereinafter granted, including without limitation, material generated from the software programs which are displayed on the screen such as icons, screen display looks etc. Information in this manual and software are subject to change without notice and does not represent a commitment on the part of SAM Limited. The software described in this manual is furnished under a license agreement and can not be reproduced or copied in any manner without prior agreement with SAM Limited, or their authorized agents. Reproduction or disassembly of embedded computer programs or algorithms prohibited. No part of this publication can be transmitted or reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission being granted, in writing, by the publishers or their authorized agents. SAM operates a policy of continuous improvement and development. SAM reserves the right to make changes and improvements to any of the products described in this document without prior notice. Contact Details Customer Support For details of our Regional Customer Support Offices and contact details please visit the SAM web site and navigate to Support/247-Support. www.s-a-m.com/support/247-support/ Customers with a support contract should call their personalized number, which can be found in their contract, and be ready to provide their contract number and details. -

Does Migration Destination Affect the Mortality Advantage of Mexican Immigrants? a Comparison of Traditional, New, and Emerging Destinations

Does Migration Destination Affect the Mortality Advantage of Mexican Immigrants? A comparison of Traditional, New, and Emerging Destinations Andrew Fenelon1 1National Center for Health Statistics, 3311 Toledo Road, Hyattsville, MD 20782 Abstract Health declines for immigrants with greater exposure to the United States, but the specific characteristics of the migration and assimilation processes that contribute to this pattern are less clear. As the Mexican population in the US has grown, it has expanded outside traditional gateways in California and Texas to new destinations throughout the US. This study examines the mortality of Mexican immigrants in Traditional versus New and Emerging destinations in the US. Using National Health Interview Survey data between 1989 and 2009 the analysis finds that Mexican immigrants in New and Emerging destinations have a significant survival advantage over their counterparts in traditional established destinations. This advantage may reflect selective migration to new destinations, superior employment prospects, or slower behavioral assimilation. US-born Mexicans do not benefit from this advantage. The results suggest that the spatial characteristics of the assimilation process are important when considering the health of immigrants. Introduction The Hispanic mortality advantage refers to the finding that the Hispanic-origin population in the United States experiences lower adult mortality rates than the non-Hispanic white population, despite lower average socioeconomic status among Hispanics. The “Hispanic Paradox” calls attention to the fact that Hispanics resemble African-Americans in terms of socioeconomic indicators but non-Hispanic whites in health and mortality indicators (Hummer, et al., 2000, Markides and Eschbach, 2011). In many studies, Hispanics exhibit higher life expectancy than non-Hispanic whites, as well as more favorable profiles with respect to non-fatal conditions such as cancer incidence and severity, heart disease, and hypertension (Eschbach, et al., 2005, Singh and Siahpush, 2002). -

601 Automated Pipetting System Operation

™ EzMate 401 / 601 Automated Pipetting System Operation Manual Ver. 2.2 Trademarks: Beckman®, Biomek® 3000 ( Beckman Coulter Inc.); Roche®, LightCycler® 480 ( Roche Group); DyNAmo™ ( Finnzyme Oy); SYBR® (Molecular Probes Inc.); Invitrogen™, Platinum® ( Invitrogen Corp.), MicroAmp® ( Applied Biosystems); Microsoft® , Windows® 7 (Microsoft Corp.). All other trademarks are the sole property of their respective owners. Copyright Notice: No part of this manual may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, for any purpose, without prior written permission of Arise Biotech Corp. Notice: This product only provides pipetting functionality. Arise Biotech Corp. does not guarantee the performance and results of the assay and reagent. Table of Contents 1. Safety Precautions ............................................................................... 1 2. Product Introduction ........................................................................... 3 2.1 Features .................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Hardware Overview ................................................................................................. 4 2.2.1 Outlook ........................................................................................................ 4 2.2.2 Control Notebook Computer........................................................................ 6 2.2.3 Automated Pipetting Module (APM).......................................................... -

The Experiential Value of Cultural Tourism Destinations Hung, Kuang-Peng; Peng, Norman; Chen, Annie

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchOnline@GCU Incorporating on-site activity involvement and sense of belonging into the Mehrabian- Russell model – The experiential value of cultural tourism destinations Hung, Kuang-peng; Peng, Norman; Chen, Annie Published in: Tourism Management Perspectives Publication date: 2019 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication in ResearchOnline Citation for published version (Harvard): Hung, K, Peng, N & Chen, A 2019, 'Incorporating on-site activity involvement and sense of belonging into the Mehrabian-Russell model – The experiential value of cultural tourism destinations', Tourism Management Perspectives, vol. 30, pp. 43-52. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please view our takedown policy at https://edshare.gcu.ac.uk/id/eprint/5179 for details of how to contact us. Download date: 29. Apr. 2020 Incorporating On-site Activity Involvement and Sense of Belonging into the Mehrabian-Russell Model - The Experiential Value of Cultural Tourism Destinations 1. INTRODUCTION Cultural products are important to post-modern society and the economy (Throsby, 2008). Among a range of different cultural products, cultural tourism destinations are significant because they provide opportunities to present a snapshot of a region’s image and history, symbolize a community’s identity, and increase the vibrancy of local economies (Chen, Peng, & Hung, 2015; Hou, Lin, & Morais, 2005; Wansborough & Mageean, 2000). -

Constructive Resistance

Constructive Resistance Lilja_9781538146484.indb 1 12/19/2020 4:22:19 PM OPEN ACCESS The author is grateful to the Swedish Research Council (VR), which has provided funds for this study. This book publishes results from three different VR projects: (1) Reconciliatory Heritage: Reconstructing Heritage in a Time of Violent Fragmentations (2016-03212); (2) The Futures of Genders and Sexualities. Cultural Products, Transnational Spaces and Emerging Communities (2014-47034); and (3) A Study of Civic Resistance and Its Impact on Democracy (2017-00881).’ Lilja_9781538146484.indb 2 12/19/2020 4:22:19 PM Constructive Resistance Repetitions, Emotions, and Time Mona Lilja ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London Lilja_9781538146484.indb 3 12/19/2020 4:22:19 PM Published by Rowman & Littlefield An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www .rowman .com 6 Tinworth Street, London SE11 5AL, United Kingdom Copyright © 2021 by Mona Lilja All photographs © Ola Kjelbye All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Control Number: 2020948897 ISBN 9781538146484 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781538146491 (epub) ∞ ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum -

Copyright by Di Wu 2016

Copyright by Di Wu 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Di Wu Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Understanding Consumer Response to the Olympic Visual Identity Designs Committee: Thomas M. Hunt, Supervisor Matthew Bowers Darla M. Castelli Marlene A. Dixon Tolga Ozyurtcu Janice S. Todd Understanding Consumer Response to the Olympic Visual Identity Designs by Di Wu, B.MAN.S.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2016 Dedication To my beloved daughter Evelyn. Acknowledgements I want to thank my parents, Weixing Wu and Jie Gao, for their unconditional love and support. I appreciate everything you have done for me. To my husband Andy Chan, thank you for your support through this journey! You are a great husband and father! To my baby girl Evelyn, you are the light and joy of my life. I love you all very much! Dr. Hunt, I can’t thank you enough for your help, encouragement, and advice that helped me to carry on and complete this long journey. Your advice and guidance of being a scholar and a parent mean so much to me. Thank you for believing in me. I am very fortunate to have you as my advisor. I also want to thank my dissertation committee members— Dr. Matt Bowers, Dr. Darla Castelli, Dr. Marlene Dixon, Dr. Tolga Ozyurtcu, and Dr. Jan Todd, for their encouragement and valuable advice. -

Robots with Lights: Overcoming Obstructed Visibility Without Colliding

Robots with Lights: Overcoming Obstructed Visibility Without Colliding G. A. Di Luna1, P. Flocchini2, S. Gan Chaudhuri3, N. Santoro4, and G. Viglietta2 1 Dipartimento di Ingegneria Informatica, Automatica e Gestionale Antonio Ruberti, Universita` degli Studi di Roma “La Sapienza”, Rome, Italy, [email protected] 2 School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, University of Ottawa, Ottawa ON, Canada, [email protected], [email protected] 3 Department of Information Technology, Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India, [email protected] 4 School of Computer Science, Carleton University, Ottawa ON, Canada, [email protected] Abstract. Robots with lights is a model of autonomous mobile computational entties operating in the plane in Look-Compute-Move cycles: each agent has an externally visible light which can assume colors from a fixed set; the lights are persistent (i.e., the color is not erased at the end of a cycle), but otherwise the agents are oblivious. The investigation of computability in this model, initially suggested by Peleg, is under way, and several results have been recently estab- lished. In these investigations, however, an agent is assumed to be capable to see through another agent. In this paper we start the study of computing when visibility is obstructable, and investigate the most basic problem for this setting, Complete Visibility: The agents must reach within finite time a configuration where they can all see each other and terminate. We do not make any assumption on a-priori knowledge of the number of agents, on rigidity of movements nor on chirality. The local coordinate system of an agent may change at each activation.