Jmn Consultant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

MINMAP South-West Region

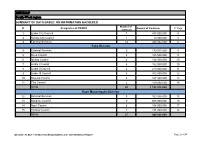

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Limbe City Council 7 475 000 000 4 2 Kumba City Council 1 10 000 000 5 3 External Services 14 440 032 000 6 Fako Division 4 External Services 9 179 015 000 8 5 Buea Council 5 125 500 000 9 6 Idenau Council 4 124 000 000 10 7 Limbe I Council 4 152 000 000 10 8 Limbe II Council 4 219 000 000 11 9 Limbe III Council 6 102 500 000 12 10 Muyuka Council 6 127 000 000 13 11 Tiko Council 5 159 000 000 14 TOTAL 43 1 188 015 000 Kupe Muanenguba Division 12 External Services 5 100 036 000 15 13 Bangem Council 9 605 000 000 15 14 Nguti Council 6 104 000 000 17 15 Tombel Council 7 131 000 000 18 TOTAL 27 940 036 000 MINMAP / PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION Page 1 of 34 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Lebialem Division 16 External Services 5 134 567 000 19 17 Alou Council 9 144 000 000 19 18 Menji Council 3 181 000 000 20 19 Wabane Council 9 168 611 000 21 TOTAL 26 628 178 000 Manyu Division 18 External Services 5 98 141 000 22 19 Akwaya Council 6 119 500 000 22 20 Eyomojock Council 6 119 000 000 23 21 Mamfe Council 5 232 000 000 24 22 Tinto Council 6 108 000 000 25 TOTAL 28 676 641 000 Meme Division 22 External Services 5 85 600 000 26 23 Mbonge Council 7 149 000 000 26 24 Konye Council 1 27 000 000 27 25 Kumba I Council 3 65 000 000 27 26 Kumba II Council 5 83 000 000 28 27 Kumba III Council 3 84 000 000 28 TOTAL 24 493 600 000 MINMAP / PUBLIC CONTRACTS -

MINMAP South-West Region

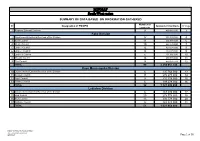

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Regional External Services 9 490 982 000 3 Fako Division 2 Départemental External Services of the Division 17 352 391 000 4 3 Buea Council 11 204 778 000 6 4 Idenau Council 10 224 778 000 7 5 Limbe I Council 12 303 778 000 8 6 Limbe II Council 13 299 279 000 9 7 Limbe III Council 6 151 900 000 10 8 Muyuka Council 16 250 778 000 11 9 Tiko Council 14 450 375 748 12 TOTAL 99 2 238 057 748 Kupe Muanenguba Division 10 Départemental External Services of the Division 6 135 764 000 13 11 Bangem Council 11 572 278 000 14 12 Nguti Council 9 215 278 000 15 13 Tombel Council 6 198 278 000 16 TOTAL 32 1 121 598 000 Lebialem Division 14 Départemental External Services of the Division 6 167 474 000 17 15 Alou Council 20 278 778 000 18 16 Menji Council 13 306 778 000 20 17 Wabane Council 12 268 928 000 21 TOTAL 51 1 021 958 000 PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION /MINMAP Page 1 of 36 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts Manyu Division 18 Départemental External Services of the Division 9 240 324 000 22 19 Akwaya Council 10 260 278 000 23 20 Eyumojock Council 6 195 778 000 24 21 Mamfe Council 7 271 103 000 24 22 Tinto Council 7 219 778 000 25 TOTAL 39 1 187 261 000 Meme Division 23 Départemental External Services of the Division 4 82 000 000 26 24 Konye Council 5 171 533 000 26 25 Kumba -

South West Assessment

Cameroon Emergency Response – South West Assessment SOUTH WEST CAMEROON November 2018 – January 2019 - i - CONTENTS 1 CONTEXT ..................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 The crisis in numbers:.................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Overall Objectives of SW Assessment ........................................................................... 5 1.3 Area of Intervention ...................................................................................................... 6 2 METHODOLOGY .......................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Assessment site selection: ............................................................................................ 8 2.2 Configuration of the assessment team: ........................................................................ 8 2.3 Indicators of vulnerability verified during the rapid assessment: ................................ 9 2.3.1 Nutrition and Health ............................................................................................. 9 2.3.2 WASH ..................................................................................................................... 9 3.1.1 Food Security ......................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Sources of Information ............................................................................................... -

2017/2018 Annual Report

Service to humanity TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 ACRONYMS .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENT ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 1. OVERVIEW OF AJESH ................................................................................................................................................. 6 1.1 Organisation Background .................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1 Vision ............................................................................................................................................................ 6 1.1.2 Mission ......................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1.3 Global objective .......................................................................................................................................... -

206 Villages Burnt in the North West and South West Regions

CHRDA Email: [email protected] Website: www.chrda.org Cameroon: The Anglophone Crisis 206 Villages burnt in the North West and South West Regions April 2019 SUMMARY The Center for Human Rights and Democracy in Africa (CHRDA) has analyzed data from local sources and identified 206 villages that have been partially, or completely burnt since the beginning of the immediate crisis in the Anglophone regions. Cameroon is a nation sliding into civil war in Africa. In 2016, English- speaking lawyers, teachers, students and civil society expressed “This act of burning legitimate grievances to the Cameroonian government. Peaceful protests villages is in breach of subsequently turned deadly following governments actions to prevent classical common the expression of speech and assembly. Government forces shot peaceful article 3 to the Four protesters, wounded many and killed several. Geneva Convention 1949 and the To the dismay of the national, regional and international communities, Additional Protocol II the Cameroon government began arresting activists and leaders to the same including CHRDA’s Founder and CEO, Barrister Agbor Balla, the then Convention dealing President of the now banned Anglophone Consortium. Internet was shut with the non- down for three months and all forms of dissent were stifled, forcing international conflicts. hundreds into exile. Also, the burning of In August 2017, President Paul Biya of Cameroon ordered the release of villages is in breach of several detainees, but avoided dialogue, prompting mass protests in national and September 2017 with an estimated 500,000 people on the streets of international human various cities, towns and villages. The government’s response was a rights norms and the brutal crackdown which led to a declaration of independence on October host of other laws” 1, 2017. -

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN ************** Paix – Travail

REPUBLIQUE DU REPUBLIC OF CAMEROUN CAMEROON ************** **************** Paix – Travail – Patrie Peace – Work – Fatherland **************** **************** REGION DE SUD OUEST SOUTH WEST REGION **************** *************** DEPARTEMENT DU LEBIALEM DIVISION LEBIALEM ************** *************** BANGEM COUNCIL COMMUNE DE BANGEM SURVEY REPORT MECHANISM OF CITIZEN CONTROL OF THE PUBLIC ACTION IN THE COUNCIL OF BANGEM May 2018 Technical and financial support of the National Community-Driven Development Program (NCDDP) in collaboration with the National Institute of Statistics (INS) Realised by: AJEMALEBU SELF HELP (AJESH) TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................. i LIST OF ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................. iv LIST OF TABLES .......................................................................................................................... v LIST OF CHARTS (FIGURES) .................................................................................................... vi LIST OF MAPS ............................................................................................................................. vi FOREWORD ................................................................................................................................ vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ -

Investors Had 38 Another One, Also Anonymously, Said: “Since They Withdrawn and the Company Was in Financial Trouble

1 2 SGSOC’S SOCIAL INVESTMENTS: A CEMETERY OF BROKEN PROMISES Summary In 2009, Sithe Global Sustainable Oils Cameroon Moreover, dozens of them were terminated before their (SGSOC) signed an agreement to develop an oil palm term, without notice or compensation. plantation in Cameroon’s Southwest region. At the time, the project was known as Herakles Farms – the SGSOC did not construct schools or hospitals, nor did name of the US investor which withdrew in 2015. it sustainably improve roads or provide access to water or electricity. SGSOC was granted a three years temporary grant by Presidential Decree on 25 November 2013. In In this report, Greenpeace Africa exposes the stark Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) and common contrast between SGSOC’s promises, and the reality commitments, the company promised to implement on the ground. Discontent is growing amongst villages a range of social investments in the villages whose in the concession area: last October, seven chiefs customary lands are included in the concession. The wrote to the President of Cameroon to announce the company would, amongst other things, provide long withdrawal of their support for and consent to the term sustainable employment, build schools and project. Moreover, 244 farmers recently filed a complaint hospitals, provide access to water and electricity, against the company for trespass to land. pay taxes to the government and ‘‘stipends’’ to local Greenpeace Africa adds its voice to these communities communities. Lack of transparency by the company to put an end to an oil palm project that has used and government bodies seriously limits the possibility fake promises and, allegedly, bribery since it started to independently assess the performance of the operating, as exposed in the Greenpeace Africa report company. -

Programming of Public Contracts Awards and Execution for the 2020

PROGRAMMING OF PUBLIC CONTRACTS AWARDS AND EXECUTION FOR THE 2020 FINANCIAL YEAR CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING LOGBOOK OF DEVOLVED SERVICES AND OF REGIONAL AND LOCAL AUTHORITIES SOUTH-WEST REGION 2021 FINANCIAL YEAR SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Regional External Services 6 219 193 000 3 2 Kumba City Council 1 100 000 000 4 Fako Division 3 Divisional External Services 6 261 261 000 5 4 Buea Council 10 215 928 000 5 5 Idenau Council 10 360 000 000 6 6 Limbe I Council 12 329 000 000 7 7 Limbe II Council 9 225 499 192 8 8 Limbe III Council 13 300 180 000 9 9 Muyuka Council 10 303 131 384 10 10 Tiko Council 8 297 100 000 11 TOTAL 78 2 292 099 576 Kupe Manenguba Division 11 Divisional External Services 2 47 500 000 12 12 Bangem Council 9 267 710 000 12 13 Nguti Council 8 224 000 000 13 14 Tombel Council 10 328 050 000 13 TOTAL 29 867 260 000 Lebialem Division 15 Divisional External Services 1 32 000 000 15 16 Alou Council 13 253 000 000 15 17 Menji Council 4 235 000 000 16 18 Wabane Council 10 331 710 000 17 TOTAL 28 851 710 000 Manyu Division 19 Divisional External Services 1 22 000 000 18 20 Akwaya Council 7 339 760 000 18 21 Eyumojock Council 8 228 000 000 18 22 Mamfe Council 10 230 000 000 19 23 Tinto Council 9 301 760 000 20 TOTAL 35 1 121 520 000 MINMAP/Public Contracts Programming and Monitoring Division Page 1 of 30 SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts Meme Division 24 -

Cameroon - South-West Region ! H Administrative Breakdowns NIGER

Cameroon - South-West Region ! h Administrative Breakdowns NIGER CHAD N N " NIGERIA " 0 0 ' !Mfom ' 0 0 3 3 ° ° 6 ! Iyahe 6 !Akumaye !Ngale !Wum CAMEROON CAR !Nkim EQUATORIAL GUINEA GABON CONGO NIGERIA NORTH-WEST AKWAYA !Bafut N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 !Acha Tugui 0 ° ° 6 6 !Ikom !Bamenda !Bali Baliben MANYU ! ! Mamfe Ayukaba ! Bachuo Akagbe ! WABANE EYUMODJOCK UPPER BAYANG LEBIALEM !Mbouda MAMFE ALOU N N " Bamougo!um " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 3 3 ° ° 5 5 ! Dschang FONTEM ! WEST ! Old Dunlop Town ! !Oban Company NGUTI ! KUPE-MANENGUBA TOKO !Kekem !Bafang !Melong SOUTH-WEST BANGEM !Passim N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 5 Calabar MUNDEMBA 5 ! !Nkongsamba !Ikot Offiong KONYE NDIAN TOMBEL !Manjo !Oron ! ISANGELE Tombel DIKOME BALUE ! Loum CAMEROON KUMBA ! KOMBO ITINDI EKONDO TITI 2ND Penja !Kumba ! KOMBO MEME !Ekondo Titi ABEDIMO KUMBA 3RD KUMBA 1ST N N " " 0 0 ' !Mbanga CENTRE ' 0 Longtoka 0 3 IDABATO ! 3 ° ° 4 BAMUSSO 4 !Ndokbélé !Mweli LITTORAL MBONGE MBONGE MUYUKA !Muyuka !Kaké !\ National capital FAKO !! Major Town WEST-COAST Bomono Gare ! BUEA ! Intermediate Town ! !Bonépoupa II ! Bomono Ba Buea ! Mbengué Small Town Mutengene ! TIKO ! International boundary Tiko Douala LIMBE !! LIMBE 2ND ! N N " 1ST Region boundary " 0 0 ' Limbe ' 0 0 ° ° 4 LIMBE 3RD 4 Department boundary Commune boundary ± River 0 10 20 E40QUATORIAL Surface Waterbody Kilometres !Edéa 8°30'0"E GUINEA 9°0'0"E 9°30'0"E 10°0'0"E Date Created: 20 Dec 2018 - Contact: [email protected] Data sources: Boundaries: OCHA, The designations employed and the presentation of material in the map(s) do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of WFP concerning Website: www.logcluster.org - Prepared by: HQ, OSE GIS ©OpenStreetMap Contributors © World Food Programme 2018 the legal or constitutional status of any country, territory, city or sea, or Map Reference: CMR_ADMIN_SudOuest_A3P_20181128 Populated places: GeoNames concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.. -

In Southwest and Littoral Regions of Cameroon

UNIVERSITY OF BUEA FACULTY OF SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES MARKETS AND MARKET CHAIN ANALYSIS FOR ERU (Gnetum spp.) IN SOUTH WEST AND LITTORAL REGIONS OF CAMEROON BY Ndumbe Njie Louis BSc. (Hons) Environmental Science A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Science of the University of Buea in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Master of Science (M.Sc.) in Natural Resources and Environmental Management July 2010 ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to the Almighty God who gave me the ability to carryout this project. To my late father Njie Mojemba Maximillian I and my beloved little son Njie Mojemba Maximillian II. iii iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the following people: Dr A. F. Nkwatoh, of the University of Buea, for his supervision and guidance; Verina Ingram, of CIFOR, for her immense technical guidance, supervision and support; Abdon Awono, of CIFOR, for guidance and comments; Jolien Schure, of CIFOR, for her comments and field collaboration. I also wish to thank the following organisations: Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), the Netherlands Development Organization (SNV), the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) and the Commission des Forets d‟Afrique Centrale (COMIFAC) for the opportunity to work within their framework and for the team spirit and support. I am also very grateful to the following collaborators: Ewane Marcus of University of Buea; Ghislaine Bongers of Wageningen University, The Netherlands and Georges Nlend of University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland for their collaboration in the field. Thanks also to Agbor Demian of Mamfe. -

CAMEROON, FIRST QUARTER 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

CAMEROON, FIRST QUARTER 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 CAMEROON, FIRST QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 162 92 263 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 111 50 316 Development of conflict incidents from March 2018 to March 2020 2 Strategic developments 39 0 0 Protests 23 1 1 Methodology 3 Riots 14 4 5 Conflict incidents per province 4 Explosions / Remote 10 7 22 violence Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 359 154 607 Disclaimer 5 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from March 2018 to March 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 CAMEROON, FIRST QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known.