Why Can't Pakistani Children Read?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

132Kv Gadap Grid Station and 132Kv Transmission Line Maymar to Gadap Grid Station

Environmental Impact Assessment of 132kV Gadap Grid Station and 132kV Transmission Line Maymar to Gadap Grid Station Final Report July, 2014 global environmental management services 2nd Floor, Aiwan-e-Sanat, ST-4/2, Sector 23, Korangi Industrial Area, Karachi Ph: (92-21) 35113804-5; Fax: (92-21) 35113806; Email: [email protected] EIA FOR K-ELECTRIC KARACHI, SINDH EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report discusses the Environmental and Socio-economic impact assessment of the proposed linked projects for electricity power supply infrastructure. The project consists of addition of 132 kV Grid having capacity of 40MVA at existing 66kV Gadap Grid Station. This power will be served from Maymar Grid Station through Single Circuit Overhead and Underground transmission line. Underground cable will loop out from Maymar Grid Station along the main road till Northern By-Pass Road at an approximate length of 1 km. That point forward, through PLDP, Overhead transmission network will begin and end at the Gadap Grid Station which is about 20 km in length. The project is proposed to fulfill the electricity requirements of the city by improvement of transmission networks. PROPONENT INTRODUCTION K-Electric Limited formerly known as Karachi Electric Supply Company Limited (KESC) is at present the only vertically-integrated power utility in Pakistan that manages the generation, transmission and distribution of electricity to the city of Karachi. The Company covers a vast area of over 6,500 square kilometers and supplies electricity to all the industrial, commercial, agricultural and residential areas that come under its network, comprising over 2.2 million customers in Karachi and in the nearby towns of Dhabeji and Gharo in Sindh and Hub, Uthal, Vindar and Bela in Balochistan. -

The Land of Five Rivers and Sindh by David Ross

THE LAND OFOFOF THE FIVE RIVERS AND SINDH. BY DAVID ROSS, C.I.E., F.R.G.S. London 1883 Reproduced by: Sani Hussain Panhwar The land of the five rivers and Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 1 TO HIS EXCELLENCY THE MOST HONORABLE GEORGE FREDERICK SAMUEL MARQUIS OF RIPON, K.G., P.C., G.M.S.I., G.M.I.E., VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, THESE SKETCHES OF THE PUNJAB AND SINDH ARE With His Excellency’s Most Gracious Permission DEDICATED. The land of the five rivers and Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 2 PREFACE. My object in publishing these “Sketches” is to furnish travelers passing through Sindh and the Punjab with a short historical and descriptive account of the country and places of interest between Karachi, Multan, Lahore, Peshawar, and Delhi. I mainly confine my remarks to the more prominent cities and towns adjoining the railway system. Objects of antiquarian interest and the principal arts and manufactures in the different localities are briefly noticed. I have alluded to the independent adjoining States, and I have added outlines of the routes to Kashmir, the various hill sanitaria, and of the marches which may be made in the interior of the Western Himalayas. In order to give a distinct and definite idea as to the situation of the different localities mentioned, their position with reference to the various railway stations is given as far as possible. The names of the railway stations and principal places described head each article or paragraph, and in the margin are shown the minor places or objects of interest in the vicinity. -

Alif Ailaan Pakistan District Education Rankings 2014

Alif Ailaan Pakistan District Education Rankings 2014 2 Table of Contents Foreword ...................................................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. Table of Contents .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 The Education Score ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Mapping change since last year ................................................................................................................... 5 Scope ............................................................................................................................................................... 5 Education Score............................................................................................................................................. 6 Access ......................................................................................................................................................... 6 Attainment ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Achievement ............................................................................................................................................. -

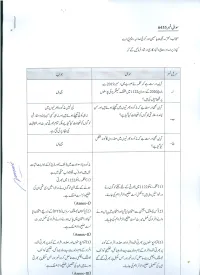

Balochistan Education Program End-Line Evaluation Report

Mmm 2 3 APR j Balochistan Education Program End-Line Evaluation Report Submitted to Save the Children Netherlands by Dr. Sarah Tirmazi March 10. 2015 Acronyms ADE Associate Diploma in Education ADEO Assistant District Education Officer AJK Azad Jammu and Kashmir Alif Ailaan An education research non-government organization (NGO) ASER Annual Status of Education Report BEP Balochistan Education Program BEMIS Balochistan Education Management Information System BESP Balochistan Education Sector Plan BoC Bureau of Curriculum CC Child Club C&W Construction and Works Department CFHE Child Focused Health Education Chowkidar Guard CRM Child Rights Movement DAC Development Assistance Committee DBDM Data Based Decision Making DDEO Deputy District Education Officer DDR Disaster Risk Reduction DEO District Education Officer or Office DEMIS District Education Management Information System ECC Early Childhood Care ECD Early Childhood Development ECE Early Childhood Education ED-LINKS Links to Learning; Education Support to Pakistan (USAID) EKN Embassy of the Kingdom of Netherlands ELM Education Leadership and Management EMIS Education Management Information Systems FATA Federally Administered Tribal Areas FGD Focus Group Discussion GB Gilgit-Baltistan GER Gross enrolment ratio GGMS Government Girls Middle School GoB Government of Balochistan HDI Human Development Index H&H Health and Hygiene ICT Islamabad Capitol Territory ICTD Information and Communication Technologies for Development IDO Innovative Development Organization IDSP Institute for Development -

State of Education in Sindh: Budgetary Analysis (FY 2010-11 to FY 2014-15)

December 2015 State of Education in Sindh: Budgetary Analysis (FY 2010-11 to FY 2014-15) Author: Dr. Shahid Habib Disclaimer Manzil Pakistan is a Karachi based think tank dedicated to developing and advocating public policy that contributes to the growth and development of Pakistan. It is registered as a Trust, no. 158 (16/5/2013). Reproduction and dissemination of any information in this report cannot be done without acknowledging Manzil Pakistan as the source. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and based on the review of primary and secondary research. All inadvertent errors in the report are those of the authors. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Education at all levels can shape the world of tomorrow, equipping individuals and societies with the skills, perspectives, knowledge and values to live and work in a sustainable manner. Therefore, quality education plays a vital role in the sustainable development as well as nation building. In nutshell, we can say, “no nation can survive without modern and quality education”. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) guarantees the right of education for all children without any discrimination. Pakistan is a member to the international accord, Universal Primary Education (UPE) and under EFA 2015 frameworks Pakistan has been assigned a target to achieve 100 percent primary school enrollment rate within 2015. Beside this, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) of the United Nation Development Program also focuses on education for all and both federal & provincial governments have a responsibility to achieve education related MDGs targets by 2015. The 1973 Constitution of Pakistan also guarantees the open access and free education to every member of the state. -

Unheard Voices: Engaging Youth of Gilgit-Baltistan

January 2015 Unheard voices: engaging youth of Gilgit-Baltistan Logo using multiply on layers Syed Waqas Ali and Taqi Akhunzada Logo drawn as seperate elements with overlaps coloured seperately Contents Executive summary 3 Introduction 5 Background and recent political history 6 1974-2009: Journey towards democratic rule 6 Gilgit-Baltistan Empowerment and Self-Governance Order 2009 7 Methodology 8 Participants 8 Questions of identity 9 Desire for provincial status 9 Counter-narrative 9 Relationship with Azad Jammu and Kashmir 10 Governance 11 How young people view the current set-up 12 Democratic deficit 12 Views on local politics and political engagement 13 Sectarianism 14 Young people’s concerns 14 Possible ways to defuse tensions 15 Education 16 Quality issues 16 Infrastructure and access 16 Further and higher education 17 Role of Aga Khan Educational Services 17 Overall perspectives on education 18 Economic issues 18 Young people’s perspectives 18 Cross LoC links and economic integration 20 Tourism potential 20 Community development 21 Conclusion 22 Cover photo: Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan © Naseer Kazmi 2 • Conciliation Resources Map of Jammu and Kashmir region © Kashmir Study Group Executive summary This research seeks to explore the sociopolitical This research explored attitudes to identity, and economic factors affecting the young people governance (including the latest political of Gilgit-Baltistan in the context of its undefined settlement established through the Gilgit-Baltistan status and the conflict over Jammu and Kashmir. Empowerment and Self-Governance Order 2009), This paper aims to highlight the largely unheard sectarianism, education and economic development voices of young people of Gilgit-Baltistan. It is based and opportunities. -

Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, As Amended

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 07/17/2013 12:53:25 PM OMB NO. 1124-0002; Expires February 28, 2014 «JJ.S. Department of Justice Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended For Six Month Period Ending 06/30/2013 (Insert date) I - REGISTRANT 1. (a) Name of Registrant (b) Registration No. Pakistan Tehreek e Insaf 5975 (c) Business Address(es) of Registrant 315 Maple street Richardson TX, 75081 Has there been a change in the information previously furnished in connection with the following? (a) If an individual: (1) Residence address(es) Yes Q No D (2) Citizenship Yes Q No Q (3) Occupation Yes • No D (b) If an organization: (1) Name Yes Q No H (2) Ownership or control Yes • No |x] - (3) Branch offices Yes D No 0 (c) Explain fully all changes, if any, indicated in Items (a) and (b) above. IF THE REGISTRANT IS AN INDIVIDUAL, OMIT RESPONSE TO ITEMS 3,4, AND 5(a). 3. If you have previously filed Exhibit C1, state whether any changes therein have occurred during this 6 month reporting period. Yes D No H If yes, have you filed an amendment to the Exhibit C? Yes • No D If no, please attach the required amendment. I The Exhibit C, for which no printed form is provided, consists of a true copy of the charter, articles of incorporation, association, and by laws of a registrant that is an organization. (A waiver of the requirement to file an Exhibit C may be obtained for good cause upon written application to the Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division, U.S. -

Alif Ailaan Update

Alif Ailaan Update February 2014 February at Alif Ailaan • Celebrating one year of Alif Ailaan • It’s In Our Hands: a campaign to highlight the stories of Pakistan’s education heroes • Expanding our reach in Sindh: building bipartisan political consensus for education reform • Deepening our ties in Balochistan: encouraging local government to take ownership of education • Endorsing the Meesaq-e-Ilm, a charter for teaching in Pakistan • Working with parents and communities on the ground 2 2 It’s In Our Hands One year of Alif Ailaan For the past year Alif Ailaan has talked about the urgency of Pakistan’s national education crisis and we have been successful in highlighting that there is a problem. To mark our first anniversary we want to inject a message of hope and purpose into the national education discourse. It’s In Our Hands is a coordinated media campaign to showcase the successes of Pakistan’s education heroes. 3 3 It’s In Our Hands Stories selected from all over Pakistan We selected 31 stories that encompass a wide range of successes, are scalable and replicable, represent public- and private-sector initiatives, and highlight exemplary individual contributions. Sham Baba – Swat . Adam Foundation . NAMAL – Mianwali . ASER . DIL Network . PCE . Sheikh Ijaz – MPA . Master Ayub PML-N . RSPN . Roshan Pakistan . Ilm Ideas – Resources for deaf children . EDO – DG Khan . HEC . Rasoolpur - Rajanpur . Insaan Dost . The Citizens . SOS Children’s Foundation (TCF) Village . Minhaj Education . Alif Laila Book Bus Society Society . Humaira Bachal’s . Umer Saif’s E- Street School Learning Project . Spelling Bee . Archdiocese . Ida Rieu . -

Spatio-Temporal Distribution of Aerosol and Cloud Properties Over Sindh Using MODIS Satellite Data and a HYSPLIT Model

Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 15: 657–672, 2015 Copyright © Taiwan Association for Aerosol Research ISSN: 1680-8584 print / 2071-1409 online doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2014.09.0200 Spatio-Temporal Distribution of Aerosol and Cloud Properties over Sindh Using MODIS Satellite Data and a HYSPLIT Model Fozia Sharif1, Khan Alam2,3*, Sheeba Afsar1 1 Department of Geography, University of Karachi, Karachi 75270, Pakistan 2 Institute of Space and Planetary Astrophysics, University of Karachi, Karachi 75270, Pakistan 3 Department of Physics, University of Peshawar, Peshawar 25120, Pakistan ABSTRACT In this study, aerosols spatial, seasonal and temporal variations over Sindh, Pakistan were analyzed which can lead to variations in the microphysics of clouds as well. All cloud optical properties were analyzed using Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) data for 12 years from 2001 to 2013. We also monitored origin and movements of air masses that bring aerosol particles and may be considered as the natural source of aerosol particles in the region. For this purpose, the Hybrid Single Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory (HYSPLIT) model was used to make trajectories of these air masses from their sources. Aerosol optical depth (AOD) high values were observed in summer during the monsoon period (June–August). The highest AOD values in July were recorded ranges from 0.41 to 1.46. In addition, low AOD values were found in winter season (December–February) particularly in December, ranges from 0.16 to 0.69. We then analyzed the relationship between AOD and Ångström exponent that is a good indicator of the size of an aerosol particle. -

6455.Pdf, PDF, 1.27MB

Overall List Along With Domicile and Post Name Father Name District Post Shahab Khan Siraj Khan PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Sana Ullah Muhammad Younas Lower Dir 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Mahboob Ali Fazal Rahim Swat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Tahir Saeed Saeed Ur Rehman Kohat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Owais Qarni Raham Dil Lakki Marwat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Ashfaq Ahmad Zarif Khan Charsadda 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Saud Khan Haji Minak Khan Khyber 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Qamar Jan Syed Marjan Kurram 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Kamil Khan Wakeel Khan PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Waheed Gul Muhammad Qasim Lakki Marwat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Tanveer Ahmad Mukhtiar Ahmad Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muhammad Faheem Muhammad Aslam PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muslima Bibi Jan Gul Dera Ismail Khan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muhammad Zahid Muhammad Saraf Batagram 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Riaz Khan Muhammad Anwar Lower Dir 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Bakht Taj Abdul Khaliq Shangla 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Hidayat Ullah Fazal Ullah Swabi 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Wajid Ali Malang Jan Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Sahar Rashed Abdur Rasheed Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Afsar Khan Afridi Ghulam Nabi PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Adnan Khan Manazir Khan Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Liaqat Ali Malik Aman Charsadda 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Adnan Iqbal Parvaiz Khan Mardan 01. -

ADB Review: News from the ADB Pakistan Resident Mission

Pakistan Resident Mission January 2020 New ADB President Masatsugu Asakawa Assumes Office "I am honored to assume the role of ADB in Fukuoka, Japan. Furthermore, in the President and to begin working in close immediate aftermath of the Global Financial cooperation with our 68 members. ADB has Crisis, he took part in the rst G20 Leaders’ been a trusted partner of the region for more Summit Meeting in his capacity as Executive than half a century, supporting strong growth that Assistant to the then Prime Minister Taro Aso. has improved the lives of people across Asia and Mr. Asakawa has had frequent engagement with the Pacic. I will strive to ensure ADB remains the Organisation for Economic Co-operation the preferred choice of its clients and partners," and Development, including as Chair of the Mr. Asakawa said. Committee on Fiscal Affairs from 2011 to 2016. Mr. Asakawa succeeds Mr. Takehiko Mr. Asakawa’s extensive international Nakao, who stepped down on 16 January 2020. experience includes service as Chief Advisor to In a career spanning close to four decades, ADB President Mr. Kimimasa Tarumizu between Mr. Asakawa has held a range of senior positions 1989 and 1992, during which he spearheaded at the Ministry of Finance of Japan, including Vice the creation of a new ofce in ADB focused on Minister of Finance for International Affairs, and strategic planning. gained diverse professional experience in Mr. Asakawa served as a Visiting Professor development policy, foreign exchange markets, at the University of Tokyo from 2012 to 2015 Masatsugu Asakawa assumes ofce as the and international tax policy. -

Girls' Education In

Girls’ education in SINDH 6.4 children in Sindh MILLION are out of school1. in Sindh There are MORE THAN 4.8 HALF MILLION 38,132 primary schools of out-of-school are missing out on children are middle or secondary and just 291 higher GIRLS2. education3. secondary schools4. Of all boys and girls aged 5–16 in Sindh5: 34% 25% are able to read a sentence BOYS GIRLS in Urdu and Sindhi. 26% 19% are able to read words BOYS GIRLS in English. 32% 24% are able to do BOYS GIRLS subtraction in arithmetic. Overview Though Sindh’s Education Sector Plan (ESP) commits to improving equity, access, quality, accountability and financing in the province, there has been little progress for girls. While the total education budget in Sindh increased by 39% between 2014–15 and 2017–18, there has not been a significant accompanying increase in school enrolment numbers. Lack of secondary schools means dropout rates remain high. Most of Sindh’s education budget is currently allocated to recurring expenses such as teachers’ salaries, which leaves little room for capital investment in infrastructure. Financial inefficiency and governance issues mean funds are not released on time and often remain unused at the district and school level. For the year 2015–2016, Rs. 134 billion of the allocated Rs. 148 billion were spent. We are calling on the Sindh The benefits of educating all girls for 12 years: government to: • Reform education sector policies to • Doubling the percentage of students finishing rectify the balance between secondary school could cut the risk of conflict in half.