Imagining “Law-Stuff” at the Newark Earthworks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newark Earthworks Center - Ohio State University and World Heritage - Ohio Executive Committee INDIANS and EARTHWORKS THROUGH the AGES “We Are All Related”

Welcoming the Tribes Back to Their Ancestral Lands Marti L. Chaatsmith, Comanche/Choctaw Newark Earthworks Center - Ohio State University and World Heritage - Ohio Executive Committee INDIANS AND EARTHWORKS THROUGH THE AGES “We are all related” Mann 2009 “We are all related” Earthen architecture and mound building was evident throughout the eastern third of North America for millennia. Everyone who lived in the woodlands prior to Removal knew about earthworks, if they weren’t building them. The beautiful, enormous, geometric precision of the Hopewell earthworks were the culmination of the combined brilliance of cultures in the Eastern Woodlands across time and distance. Has this traditional indigenous knowledge persisted in the cultural traditions of contemporary American Indian cultures today? Mann 2009 Each dot represents Indigenous architecture and cultural sites, most built before 1491 Miamisburg Mound is the largest conical burial mound in the USA, built on top of a 100’ bluff, it had a circumference of 830’ People of the Adena Culture built it between 2,800 and 1,800 years ago. 6 Miamisburg, Ohio (Montgomery County) Picture: Copyright: Tom Law, Pangea-Productions. http://pangea-productions.net/ Items found in mounds and trade networks active 2,000 years ago. years 2,000 active networks trade and indicate vast travel Courtesy of CERHAS, Ancient Ohio Trail Inside the 50-acre Octagon at Sunrise 8 11/1/2018 Octagon Earthworks, Newark, OH Indigenous people planned, designed and built the Newark Earthworks (ca. 2000 BCE) to cover an area of 4 square miles (survey map created by Whittlesey, Squier, and Davis, 1837-47) Photo Courtesy of Dan Campbell 10 11/1/2018 Two professors recover tribal knowledge 2,000 years ago, Indigenous people developed specialized knowledge to construct the Octagon Earthworks to observe the complete moon cycle: 8 alignments over a period of 18 years and 219 days (18.6 years) “Geometry and Astronomy in Prehistoric Ohio” Ray Hively and Robert Horn, 1982 Archaeoastronomy (Supplement to Vol. -

Archaeologist Volume 41 No

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 41 NO. 4 FALL 1991 Published by THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF OHIO The Archaeological Society of Ohio MEMBERSHIP AND DUES Annual dues to the Archaeological Society of Ohio are payable on the first of January as follows: Regular membership $15.00; husband and TERM wife (one copy of publication) $16.00; Life membership $300.00. A.S.O. OFFICERS EXPIRES Subscription to the Ohio Archaeologist, published quarterly, is included President James G. Hovan, 16979 South Meadow Circle, in the membership dues. The Archaeological Society of Ohio is an Strongsville, OH 44136, (216) 238-1799 incorporated non-profit organization. Vice President Larry L. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue SE, East Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 BACK ISSUES Exec. Sect. Barbara Motts, 3435 Sciotangy Drive, Columbus, OH 43221, (614) 898-4116 (work) (614) 459-0808 (home) Publications and back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist: Recording Sect. Nancy E. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue Ohio Flint Types, by Robert N. Converse $ 6.00 SE, East Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 Ohio Stone Tools, by Robert N. Converse $ 5.00 Treasurer Don F. Potter, 1391 Hootman Drive, Reynoldsburg, Ohio Slate Types, by Robert N. Converse $10.00 OH 43068, (614)861-0673 The Glacial Kame Indians, by Robert N. Converse $15.00 Editor Robert N. Converse, 199 Converse Dr., Plain City, OH Back issues—black and white—each $ 5.00 43064,(614)873-5471 Back issues—four full color plates—each $ 5.00 Immediate Past Pres. Donald A. Casto, 138 Ann Court, Lancaster, OH 43130, (614) 653-9477 Back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist printed prior to 1964 are generally out of print but copies are available from time to time. -

FREE Trial Issue (PDF)

ANCIENTANCIENTANCIENT AMERICANAMERICANAMERICAN© ArchaeologyArchaeology ofof thethe AmericasAmericas BeforeBefore ColumbusColumbus A Mysterious Discovery Beneath the Serpent’s Head Burrows Cave Marble Stone isIs RecentlyRecently Carved Copper Ingots Manufactured in Louisiana Stonehenge Compared to the Earthworks of the Ohio Burial Mounds of the Upper Mississippi Glozel Tablets Reviewed DDwwaarrffiissmm Ancient Waterways Revealed on Burrows Cave iinn AAnncciieenntt Mapstone MMeessooAAmmeerriiccaa VVooll..uummee 1144 •• IIssssuuee NNuummbbeerr 8899 •• $$77..9955 1993-94 Ancient American Six Issues in Original Format Now Available: 1 thru 6 • AA#1. Petroglyphs of Gorham • AA#2. Burrows Cave: Fraud or Find of the Century • AA#3. Stones of Atlantis • AA#4. Face of Asia • AA#5. Archives of the Past: Stone, Clay, Copper • AA#6. Vikings Any 2 for $30.00 + 2.50 $19.95 ea. plus 2.50 post Windows and MacIntosh Two or more $15.00 ea. 1994-95 Ancient American Six Issues in Original Format Now Available: 7 thru 12 • AA#7. Ruins of Comalcalco • AA#8. Ancient Egyptians Sail to America • AA#9. Inca Stone • AA#10. Treasure of the Moche Lords • AA#11. The Kiva: Gateway for Man • AA#12. Ancient Travelers to the Americas All 3 for $45.00 + 3.00 $19.95 ea. plus 2.50 post Two or more $15.00 ea. Windows and MacIntosh Mystic Symbol Mark of the Michigan Mound Builders The largest archaeological tragedy in the history of the USA. Starting in the 1840’s, over 10,000 artifacts removed from the earth by pioneers clearing the land in Michigan. Stone, Clay and Copper tablets with a multitude of everyday objects, tools and weapons. -

Glenford Stone “Fort” and Other Stone Constructions in Ohio and Beyond

GLENfoRD STONE “FORT” AND OTHER STONE CONSTRUCTIONS IN OHIO AND BEYOND Norman Muller When we think of the ancient history of Ohio, the tant study of aboriginal stone wall sites in Georgia and Mound Builders come to mind, particularly the spec- neighboring states, listed six stone wall sites in Ohio, tacular geometric earthen mounds that the Hopewell four of which were built with a mixture of earth and Indians constructed two thousand years ago in and stone. They were: Butler County site near the Great around the town of Newark. Except for the Great Miami River, Miami County site on the left bank of Circle and the Octagon, the latter of which is part of the Great Miami River, Fort Hill, and the Spruce Hill a municipal golf course and was preserved because of Works. Two other sites did not make Smith’s list: the it, nearly all of the other features within Newark and Stone Fort on Flint Ridge, and the Pollock Site. First, beyond were obliterated in the nineteenth century for though, let us look at Spruce Hill Works and Fort Hill agricultural purposes. Less well known are those struc- in a bit more detail: tures and walls built completely of stone or a composite Spruce Hill Works in Ross County (Figure 1) is a of earth and stone. Glenford “Fort” was constructed en- large 140-acre hilltop with a two-and-a-quarter mile long tirely of stone, and it is the main subject of this paper. stone wall around the perimeter, which was originally But we find other structures in Ohio also built of stone, some wholly and others partly. -

Public Works Projects at Serpent Mound State Memorial

NEW DEAL, NEW SERPENT: PUBLIC WORKS PROJECTS AT SERPENT MOUND STATE MEMORIAL Rory Krupp Abstract Archival research has identified documents at the Ohio History Connection related to Serpent Mound archaeology. The current understanding of the site is that Frederic W. Putnam restored Serpent Mound in the 1880s and converted the surrounding property into a public park. The Ohio History Connection’s State Archives series and New Deal agency records indicate that the Serpent Mound was again restored in 1934–1935. Consequently, today’s Serpent Mound and its surrounding landscape are in reality a New Deal construct based largely on landscaping principles developed by the National Park Service in the 1920s and 1930s. Depression-era agencies’ financial prioritization on wages and not materials seems to indicate that fill used in the restoration originated in the park to save money and may have been associ- ated with restroom construction in 1934–1935. Consequently, the Fort Ancient Baum Focus material located in the Serpent Mound appears to originate from elsewhere within the park and is in the mound as a result of the New Deal restoration. Background suffered from wandering cattle and looters who failed to backfill while looking for artifacts. These Serpent Mound was first recorded by actions, exacerbated by rain, had promoted the Ephraim G. Squier and Dr. Edwin Davis in 1846, mound’s erosion. and it was included in their Ancient Monuments Prompted by Putnam, who was alarmed by the of the Mississippi Valley in 1848 (Squier and Da- mound’s rapid deflation, a group of Boston soci- vis 1848). -

Archaeologist Volume 50 No

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 50 NO. 2 SPRING 2000 PUBLISHED BY THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF OHIO The Archaeological Society of Ohio MEMBERSHIP AND DUES Annual dues to the Archaeological Society of Ohio are payable on the first of TERM January as follows: Regular membership $20.00; husband and wife (one copy EXPIRES A.S.O. OFFICERS of publication) $21.00; Individual Life Membership $300. Husband and wife Life Membership $500. Subscription to the Ohio Archaeologist, published 2000 Interim President Carmel "Bud" Tackett, 906 Charleston Pike, quarterly, is included in the membership dues. The Archaeological Society of Chillicothe, OH 45601 (740) 772-5431. Ohio is an incorporated non-profit organization. 2000 Vice President Walt Sperry, 6910 Range Line Road, BACK ISSUES Mt. Vernon, OH (740) 393-2314. Publications and back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist: 2000 Treasurer Gary Kapusta, 3294 Herriff Rd., Ravenna, OH 44266 Ohio Flint Types, by Robert N. Converse $40.00 add $4.50 P-H 2287, (330) 296-2287. Ohio Stone Tools, by Robert N. Converse $ 8.00 add $1.50 P-H 2000 Executive Secretary Len Weidner, 13706 Robins Road, Ohio Slate Types, by Robert N. Converse $15.00 add $1.50 P-H Westerville, OH 43081 (740) 965-2868. The Glacial Kame Indians, by Robert N. Converse$20.00 add $2.50 P-H 1980's & 1990's $ 6.00 add $1.50 P-H 2002 Editor Robert N. Converse, 199 Converse Drive, Plain City, 1970's $ 8.00 add $1.50 P-H OH 43064, (614)873-5471. 1960's $10.00 add $1.50 P-H 2000 Technical Advisor Jane Weidner, 13706 Robins Road, Back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist printed prior to 1964 are gener Westerville, OH 43081, (740) 965-2868. -

Place and Phenomenology

Place and Phenomenology Edited by Janet Donohoe ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD INTERNATIONAL I London • Neiv York I Contents Introduction vii PART I: PLACE AND THE EXISTENTIAL 1 1 The Openness of Places Edward Relph 3 2 The Double Gift—Place and Identity Robert Miigerauer 17 3 The Idea of an Existential Ecology Boh Sandmeyer 39 PARTH: SACRED PLACES 57 4 Nature, Place, and the Sacred Anne Buttimer 59 5 From the Land Itself: The Himalayas as Sacred Landscape John Cameron 75 6 The Ambiguity of "Sacred Space": Superabundance, Contestation, and Unpredictability at the Earthworks of Newark, Ohio Lindsay Jones 97 PART HI: PLACE, EMBODIMENT, AND HOME 125 7 The Living Arena of Existential Health: Space, Autonomy, and Embodiment Kirsten Jacobson 127 vi Contents 8 Environed Embodiment and Geometric Space Adam Konopka 143 9 Nature as Home: A Gendered Phenomenology of Place Trish Glazebrook 163 PART IV: PLACES REDISCOVERED 185 10 Intraterrestrials: Landing Sites David Wood 187 11 Indeterminacy in Place: Rivers as Bridge and Meandering as Metaphor Irene J. Klaver 209 12 Lifeworld Transit Difference Jonathan Maskit 227 PARTV: PLACE AND PHENOMENOLOGICAL LIMITS 245 13 Architecture, Place, and Phenomenology: Buildings as Lifeworlds, Atmospheres, and Environmental Wholes David Seamon 247 14 Genetic Phenomenology and the Erasure of Place Janet Donohoe 265 15 Unprecedented Experience and Levinas's Heideggerian Idolatry of Place Bruce B. Jam 281 Bibliography 297 Index 319 List of Contributors 325 Chapter Six The Ambiguity of "Sacred Space" Superabundance, Contestation, and Unpredictability at the Earthworks of Newark, Ohio Lindsay Jones Few places demonstrate more vividly than the Earthworks of Newark, Ohio, that claims to the "sacredness" of a place are made with far greater frequency than rigor, precision, or consistency. -

Local and “Global” Perspectives on the Middle Woodland Southeast

Archived version from NCDOCKS Institutional Repository http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/asu/ Local and ‘‘Global’’ Perspectives on the Middle Woodland Southeast By: Alice P. Wright Abstract During the Middle Woodland period, from 200 BC to AD 600, south-eastern societies erected monuments, interacted widely, and produced some of the most striking material culture of the pre-Columbian era, but these developments are often overshadowed by the contemporaneous florescence of Hopewell culture in Ohio. I argue that the demonstrable material links between the Middle Woodland Southeast and Midwest demand that we cease to analyze these regional archaeological records in isolation and adopt multiscalar perspectives on the social fields that emerged from and impacted local Middle Woodland societies. In synthesizing recent research on Middle Woodland settlement, monumentality, interaction, and social organization, I make explicit comparisons between the Middle Woodland Southeast and Ohio Hopewell, revealing both commonalities and contrasts. New methodological approaches in the Southeast, including geophysical survey techniques, Bayesian chronological modeling, and high-resolution provenance analyses, promise to further elucidate site-specific histories and intersite connectivity. By implementing theoretical frameworks that simultaneously consider these local and global dimensions of Middle Woodland sociality, we may establish the southeastern Middle Woodland period as an archaeological context capable of elucidating the deep history of the Eastern Woodlands -

Hopewell Conference Final Program and Abstracts.Pdf

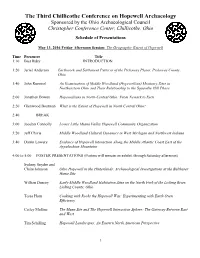

The Third Chillicothe Conference on Hopewell Archaeology Sponsored by the Ohio Archaeological Council Christopher Conference Center, Chillicothe, Ohio Schedule of Presentations May 13, 2016 Friday Afternoon Session: The Geographic Extent of Hopewell Time Presenter Title 1:10 Bret Ruby INTRODUCTION 1:20 Jerrel Anderson Earthwork and Settlement Patterns of the Pickaway Plains, Pickaway County, Ohio 1:40 John Rummel An Examination of Middle Woodland (Hopewellian) Mortuary Sites in Northeastern Ohio and Their Relationship to the Squawkie Hill Phase 2:00 Jonathan Bowen Hopewellians in North-Central Ohio: From Newark to Esch 2:20 Glenwood Boatman What is the Extent of Hopewell in North Central Ohio? 2:40 BREAK 3:00 Jocelyn Connolly Lower Little Miami Valley Hopewell Community Organization 3:20 Jeff Chivis Middle Woodland Cultural Dynamics in West Michigan and Northwest Indiana 3:40 Darrin Lowery Evidence of Hopewell Interaction Along the Middle Atlantic Coast East of the Appalachian Mountains 4:00 to 5:00 POSTER PRESENTATIONS (Posters will remain on exhibit through Saturday afternoon) Sydney Snyder and Claire Johnson Ohio Hopewell in the Hinterlands: Archaeological Investigations at the Balthaser Home Site Willian Dancey Early-Middle Woodland Habitation Sites on the North Fork of the Licking River, Licking County, Ohio Tessa Horn Cooking with Rocks the Hopewell Way: Experimenting with Earth Oven Efficiency Cailey Mullins The Mann Site and The Hopewell Interaction Sphere: The Gateway Between East and West Tim Schilling Hopewell Landscapes: An -

Ritualised Craft Production at the Hopewell Periphery: New Evidence from the Appalachian Summit

Archived version from NCDOCKS Institutional Repository http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/asu/ Ritualised Craft Production at The Hopewell Periphery: New Evidence From The Appalachian Summit By: Alice P. Wright & Erika Loveland Abstract Ritual items made of thin mica sheet are among the most spectacular of the special objects from the Hopewell sites of the Ohio Valley. Hitherto it has generally been believed that the mica was imported in raw material form from sources in the Appalachian Summit and cut into shape in the Hopewell core. Recent excavations at Garden Creek, a ritual enclosure on the margin of the source area, throws doubt on this model through extensive evidence for mica-working at this site. The Garden Creek community may have been drawn into the Hopewell sphere through its proximity to the mica sources, and the people of Garden Creek may have carried cut mica and crystal quartz as offerings to the major Hopewell centres in the course of pilgrimage. Alice P. Wright & Erika Loveland (2015) "Ritualised Craft Production at The Hopewell Periphery: New Evidence From The Appalachian Summit" Antiquity 89 pp. 137-153 Version of Record Available From (www.cambridge.org) Ritualised craft production at the Hopewell periphery: new evidence from the Appalachian Summit Alice P. Wright & Erika Loveland Ritual items made of thin mica sheet 0 km 1000 are among the most spectacular of the special objects from the Hopewell sites of N the Ohio Valley. Hitherto it has generally been believed that the mica was imported Washington, D.C. in raw material form from sources in the Appalachian Summit and cut into shape Garden Creek in the Hopewell core. -

1 Religious Innovation at the Emerald Acropolis

Religious Innovation at the Emerald Acropolis: Something New under the Moon Timothy R. Pauketat and Susan M. Alt Submitted for Something New under the Sun: Perspectives on the Interplay of Religion and Innovation, edited by D. Yerxa, Bloomsbury Press, London. Among the ancients, a city was never formed by degrees, by the slow increase in the number of men and houses. They founded the city at once, all entire in a day … [and it] was always a religious act. (Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges, 1864) Fundamental relationships between religion and innovation, specifically as these were intertwined at the founding moments of ancient cities, are poorly understood. In the last twenty years, religion has become a focus of considerable concern in archaeology (Insoll 2011). But many archaeologists assume that religion is best defined as a set of codified conservative beliefs that endure despite the actions of people and the turnings of the world. Certain archaeological approaches to religion are even ethnocentric, hung up on religions as institutions and orthodoxies, swaying analysts to ignore the unofficial, Quotidian, magical and spiritual practices of people less often depicted in official art and iconography (following Scott 1990). Formal, belief-bound, institutional definitions of religion inhibit considering the religious dimensions of many kinds of relationships between people, places, things, and more. This is 1 particularly problematic in non-modern historical eras where people related to the world as if their histories, identities, and futures were bound to non-human sentient beings or other animate powers (Alberti, et al. 2011; Bird-David 1999; Harvey 2006). In those times and places, people lived and breathed their religions daily. -

MONUMENTAL GRANDEUR of the MISSISSIPPI VALLEY” by MEGAN C

The Mounds of Native North America “MONUMENTAL GRANDEUR of the MISSISSIPPI VALLEY” BY MEGAN C. KASSABAUM 6 EXPEDITION Volume 57 Number 2 arthen mounds have been constructed in the eastern United States for well over 5,000 years. From early beginnings in the Lower Mississippi Valley through the ongoing mound building ceremonies of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, mounds have always played important roles in the ritual, social, and Epolitical lives of Native American groups. They vary widely in terms of form and function and many archaeologists have dedicated their careers to understanding the various meanings the mounds have had both through time and across space. Artist’s interpretation of the mounds at Watson Brake in Ouachita Parish, Louisiana. The tallest mound, at the north end of the site, is a 25-foot- tall conical mound. Another tall conical mound sits to the south, while most of the others are relatively low, dome-shaped mounds. Rendering by Steven N. Patricia. EXPEDITION Fall 2015 7 Te Mississippi River forms the 4th largest watershed in the world, running over 2,300 miles from Minnesota to Louisiana. When the river became known to Euro- MINNEESSOTA peans in 1541, it had already been a center of Native American resource procurement, trade, communication, WISCONSIN and travel for over 12,000 years. Due to its natural abun- dance, the Mississippi Valley was able to support large MICHIGAN Effigy Mounds prehistoric populations and, beginning in the Middle Archaic period (6000–2000 BCE), these groups signaled IOWA the river’s importance by building earthen monuments Newark throughout the region.