DOCUMENT RESUME Creative America. a Report to the President

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

You Can Double Your Gift to Extra Mile Education Foundation. Many Companies Will Match Their Employee's Contribution. Below I

You can double your gift to Extra Mile Education Foundation. Many companies will match their employee’s contribution. Below is a partial list of corporations and business who provide matching gifts. Please contact your Human Resource representative to help support children and their families seeking a values-based quality education. CBS GE Fund 3M CIGNA Foundation Gannett CNA Insurance Company Gap Foundation ADC Telecommunications, Inc. CNG General Electric AES Beaver Valley CR Bard General Mills AK Steel Corporation Cadence General Motors AMD Matching Gifts Program Design Systems, Inc. Gillette Company AMGEN Foundation (The) Capital Group Companies Charitable GlaxoSmithKline Foundation AT&T Casey Matching Gift Program Goldman, Sachs & Company Alcatel-Lucent Certain Teed Goodrich Corporation Alcoa Channel Craft Google Allegheny Energy Co., Inc. Chevron Texaco Corporation Allegheny Power Chicago Title & Trust Company H.J. Heinz Company Allegheny Technologies, Inc. Chubb & Son, Inc. Hamilton Sundstrand Alliant Techsystems Citigroup Harcourt, Inc. Altria Group, Inc. Citizens Bank Harsco Corporation Altria Program Cleveland H. Dodge Foundation, Inc. Hartford Steam Boiler Computer Associates International, Inc. American Express Financial Advisors Hewlett Packard Company Corning Incorporated American International Group Highmark Cyprus Amax Ameritech Hillman Company (The) Ameriprise Financial Home Depot, Inc. Del Monte Foods Company Aramark Honeywell Houghton Mifflin Deluxe Corporation Arco Chemical Company Dictaphone Corporation ARCO IBM Corporation Dominion Foundation Armco, Inc. International Minerals & Chemical Co. Astorino EQT Corporation Automatic Data Processing J.P. Morgan Chase ERICSSON AXA Financial/Equitable John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance. Co. East Suburban Medical Supply Johnson & Johnson Eaton Corporation B.F. Goodrich Johnson Controls Eli Lilly Company BNY Mellon Juniper Networks (The) Emerson Electric BP America Erie Insurance Group Baxter Allegiance Kaplan, Inc. -

Membership Directory Is Designed to Help Connect You with AMI Staff and with Others in the Industry Who Have Also Chosen to Invest in the Institute

SPRING 2010 Membership D i r e c t o r y AMERICAN MEAT INSTITUTE AMERICAN MEAT INSTITUTE J. Patrick Boyle President and CEO Dear AMI Member, For more than a century, the American Meat Institute (AMI) has strived to provide effective representation in Washington before Congress and the regulatory agencies. We also speak on behalf of the industry to the media, professional organizations and in other public forums. Our experts manage a comprehensive research agenda, advocate for free and open trade, and organize a host of educational and networking opportunities. While many things have changed in the 104 years since our founding, there are some constants too, like our commitment to represent this great industry of ours honestly and effectively in Washington DC. We are proud that the Institute is the industry’s oldest and largest trade association. Our longevity and our size can be attributed to the diversity amongst our member companies. While we are fortunate to represent many large, multi-national companies, our greatest strength and political credibility comes from our many small and medium sized companies who call AMI their association. In fact, 80 percent of our members are actually small and medium sized companies. We believe the industry benefits when diverse companies with unique ideas and expertise collaborate to make our industry better and our Institute stronger. This AMI membership directory is designed to help connect you with AMI staff and with others in the industry who have also chosen to invest in the Institute. We believe that we succeed when you succeed. Please let us know how we may be of service to you. -

The History of Wake Forest University (1983–2005)

The History of Wake Forest University (1983–2005) Volume 6 | The Hearn Years The History of Wake Forest University (1983–2005) Volume 6 | The Hearn Years Samuel Templeman Gladding wake forest university winston-salem, north carolina Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication data Names: Gladding, Samuel T., author. Title: History of Wake Forest University Volume 6 / Samuel Templeman Gladding. Description: First hardcover original edition. | Winston-Salem [North Carolina]: Library Partners Press, 2016. | Includes index. Identifiers: ISBN 978-1-61846-013-4. | LCCN 201591616. Subjects: LCSH: Wake Forest University–History–United States. | Hearn, Thomas K. | Wake Forest University–Presidents–Biography. | Education, Higher–North Carolina–Winston-Salem. |. Classification: LCCLD5721.W523. | First Edition Copyright © 2016 by Samuel Templeman Gladding Book jacket photography courtesy of Ken Bennett, Wake Forest University Photographer ISBN 978-1-61846-013-4 | LCCN 201591616 All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction, in whole or in part, in any form. Produced and Distributed By: Library Partners Press ZSR Library Wake Forest University 1834 Wake Forest Road Winston-Salem, North Carolina 27106 www.librarypartnerspress.org Manufactured in the United States of America To the thousands of Wake Foresters who, through being “constant and true” to the University’s motto, Pro Humanitate, have made the world better, To Claire, my wife, whose patience, support, kindness, humor, and goodwill encouraged me to persevere and bring this book into being, and To Tom Hearn, whose spirit and impact still lives at Wake Forest in ways that influence the University every day and whose invitation to me to come back to my alma mater positively changed the course of my life. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Elynor Williams

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Elynor Williams Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Williams, Elynor, 1946- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Elynor Williams, Dates: April 19, 2012 Bulk Dates: 2012 Physical 7 uncompressed MOV digital video files (3:19:26). Description: Abstract: Corporate executive Elynor Williams (1946 - ) became Sara Lee Corporation’s first African American corporate officer serving as vice president for public responsibility. Williams was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on April 19, 2012, in Chicago, Illinois. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2012_048 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Corporate executive Elynor A. Williams was born on October 27, 1946 in Baton Rouge, Louisiana to Albert and Naomi Williams. She graduated from Central Academy in Palatka, Florida before receiving her B.A. degree in home economics from Spelman College in 1966. Williams then joined Eugene Butler High School in Jacksonville, Florida as a home economics teacher. In 1968, she became an editor and publicist for General Foods Corporation in White Plains, New York. Williams received her M.A. degree in communication arts from Cornell University in 1973. At Cornell, she worked as a tutor for special education projects. Following the completion of her education, Williams became a communication specialist for North Carolina Agricultural Extension Service. In 1977, she became a senior public relations specialist for Western Electric Company in Greensboro, North Carolina. Williams served as director of corporate affairs for Sara Lee Corporation’s Hanes Group in Winston-Salem, North Carolina from 1983 to 1986 and director of public affairs for the Sara Lee Corporation in Chicago, Illinois from 1985 to 1990. -

Networks, Institutions, Strategy, and Structure

How did we get The Coming from here… …to here… Collapse of the Corporation …and where Prof. Jerry Davis do we Chinese Economists Society 15 March 2015 go next? 1889-2012* ~2007-2011 The high water mark of corporate capitalism in the United States: 1973 The golden era of corporate society • “The big enterprise is the true symbol of our social order…In the industrial enterprise the structure which actually underlies all our society can be seen…” (Drucker, 1950) • “The whole labor force of the modern corporation is, insofar as possible, turned into a corps of lifetime employees, with great emphasis on stability of employment” and thus “Increasingly, membership in the modern corporation becomes the single strongest social force shaping its career members…” (Kaysen, 1957) • “Organizations are the key to society because large organizations have absorbed society. They have vacuumed up a good part of what we have always thought of as society, and made organizations, once a part of society, into a surrogate of society” (Perrow, 1991) 3 1 Some premises of the corporate-centered society 1. The typical corporation makes tangible products 2. Corporate ownership is broadly dispersed 3. Corporate control is concentrated 4. Corporations aim to grow bigger in assets and 1.The typical corporation makes number of employees 5. Corporations live a long time tangible products 5 6 Manufacturing employment is increasingly rare The largest employers have shifted from manufacturing to retail and other services 10 Largest US Corporate Employers, 1960-2010 Since January 2001, the US has shed 5 1960 1980 2010 million jobs in GM AT&T WAL-MART Wal-Mart now manufacturing– AT&T GM TARGET employs roughly ~ one in three FORD FORD UPS GE GE KROGER as many US STEEL SEARS SEARS HLDGS Americans as the As of March 2009, SEARS IBM “AT&T” 20 largest more Americans were A&P ITT HOME DEPOT manufacturers unemployed than EXXON KMART WALGREEN combined Proportion of US private labor force employed in were employed in BETH. -

NEA Chronology Final

THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS 1965 2000 A BRIEF CHRONOLOGY OF FEDERAL SUPPORT FOR THE ARTS President Johnson signs the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act, establishing the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, on September 29, 1965. Foreword he National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act The thirty-five year public investment in the arts has paid tremen Twas passed by Congress and signed into law by President dous dividends. Since 1965, the Endowment has awarded more Johnson in 1965. It states, “While no government can call a great than 111,000 grants to arts organizations and artists in all 50 states artist or scholar into existence, it is necessary and appropriate for and the six U.S. jurisdictions. The number of state and jurisdic the Federal Government to help create and sustain not only a tional arts agencies has grown from 5 to 56. Local arts agencies climate encouraging freedom of thought, imagination, and now number over 4,000 – up from 400. Nonprofit theaters have inquiry, but also the material conditions facilitating the release of grown from 56 to 340, symphony orchestras have nearly doubled this creative talent.” On September 29 of that year, the National in number from 980 to 1,800, opera companies have multiplied Endowment for the Arts – a new public agency dedicated to from 27 to 113, and now there are 18 times as many dance com strengthening the artistic life of this country – was created. panies as there were in 1965. -

TYSON FOODS, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter) ______

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K [X] Annual Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the fiscal year ended October 1, 2016 [ ] Transition Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the transition period from to 001-14704 (Commission File Number) ______________________________________________ TYSON FOODS, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) ______________________________________________ Delaware 71-0225165 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) incorporation or organization) 2200 West Don Tyson Parkway, Springdale, Arkansas 72762-6999 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (479) 290-4000 Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Class A Common Stock, Par Value $0.10 New York Stock Exchange Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: Not Applicable Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes [ ] No [ X ] Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes [ ] No [X] Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Sara Lee Now. Sara Lee Corporation

254 Pg 89 IBC_BC_Spine R3:Layout 8/26/09 8:51 PM Page 90 254254 Pg Sara89 IBC_BC_Spine Lee 09AR R7:Layout R3:Layout 1 8/26/09 8:368:51 PM Page c191 2009 Annual Report Sara Lee now. Sara Lee Corporation 2009 Annual Report Sara Lee Corporation 3500 Lacey Road Downers Grove, IL 60515-5424 + 1.800.SARA.LEE + 1.630.598.6000 www.saralee.com 254 Sara Lee 09AR R7:Layout 1 8/26/09 8:36 PM Page c2 254 Pg 89 IBC_BC_Spine R4:Layout 9/1/09 7:09 PM Page 89 Financial highlights Investor information Corporate Information 2009 Annual Meeting of Stockholders Sara Lee Corporation’s 2009 annual report and proxy statement Thursday, October 29, 2009 together contain substantially all the information presented in the 9:30 – 10:30 a.m. Central Time (CDT) corporation’s annual report on Form 10-K filed with the Securities Chicago Marriott Downtown Magnificent Mile 1 1 Dollars in millions except per share data Years ended June 27, 2009 June 28, 2008 % Change and Exchange Commission. Individuals interested in receiving the 540 North Michigan Avenue Results of Operations Form 10-K, investor packets or other corporate literature, as well Chicago, IL 60611 Continuing operations as our latest quarterly earnings announcement, via first-class mail Net sales $12,881 $13,212 (2.5) % should call or write to the Investor Relations Department. This Stock Listing Income before income taxes 588 160 NM information also is available via the Internet with links to our Sara Lee Corporation’s common stock is listed under the symbol Income (loss) 364 (41) NM brand and division Web sites. -

Matching Gift Companies American Express Company American International Group, Inc

Matching Gift Companies American Express Company American International Group, Inc. Matching Gifts are a vital part of our fundraising efforts. You can increase your contribution to American Nuclear Insurers ASH if your company has a Matching Gifts American Ref-Fuel Company Program. If your company is listed below American Trading and please contact your personnel office to obtain a Production Corporation matching gift form and return it with your Ameriprise Financial, Inc contribution, or contact the Development AmerUs Group Company Office at 504-269-1210 Amgen, Inc. Amica Companies Thank you for your support! AmSouth BanCorp Foundation Anadarko Petroleum Corporation List of Participating Companies Anchor Brewing Co. A & E Television Networks Anchor Capital Advisors, LLC Abbott Laboratories Anchor Russell Capital Abell-Hanger Foundation Advisors, Inc. Aboda, Inc. Andersons, Inc., The Acco Brands Corporation Andrew Corporation ACE Group Anheuser- Busch Acxiom Corporation Apache Corporation Adaptec Inc APC - MGE (American Power Conversion) ADC Telecommunications, Inc. Applera Corporation Administaff, Inc. Arch Chemicals Inc. Adobe Systems, Inc. Archer-Daniels Midland Advanced Financial Services, Inc. Argonaut Group, Inc. Advanced Micro Devices Arkwright Foundation Advanta Corp. Armstrong World Industries Advisor Technologies Art Technology Group, Inc. AES Corporation, The Arthur J. Gallagher & Co. Aetna, Inc. Aspect Software, Inc. AIG Assent LLC Air Liquide USA LLC Assurant Employee Benefits AK Steel Holding Corporation Assurant Health Albemarle Corporation Assurant, Inc. Alliant Energy Corporation AT&T Alliant Energy Corporation (retirees) Autodesk, Inc. Alliant Techsystems, Inc. Autoliv North America Allianz Global Risks US Autozone Insurance Company Automatic Data Processing, Inc. Allied World Assurance (U.S.) Inc Aviva USA Altria Group, Inc. -

Sara Lee Annual Report

GIVING 1998| 1999 Cover: Lemons on a Pewter Plate (Les citrons au plat d’étain) by Henri Matisse, (1926, reworked 1929). A Millennium Gift of Sara Lee Corporation given to The Art Institute of Chicago. Our GIVING is focused on three areas: the arts, women and the special needs of those who are hungry, homeless and living in disadvantaged circumstances. In this way, Sara Lee is truly helping to nourish mind, spirit & body SARA LEE GIVING Contents Awakening our Mind page 7 Renewing our Spirit page 15 Energizing our Body page 23 Grant Recipient List page 29 Matching Grants List page 37 SARA LEE GIVING Sara Lee Corporation is a global manufacturer and marketer of high-quality, brand-name products for consumers throughout the world. Headquartered in Chicago, Sara Lee has operations in 40 countries and markets its products in more than 140 nations. Its 138,000 employees are committed to creating shareholder value and improving the quality of life in their communities. www.saralee.com The Sara Lee Foundation is the philanthropic arm of Sara Lee Corporation and is operated as a separate entity with its own board of directors. Through the Foundation, Sara Lee is committed to making a lasting and positive impact on the communities where its employees live and work. This is accomplished by giving at least 2% of Sara Lee Corporation’s annual U.S. pretax income, in cash and product contributions, to nonprofit organizations. www.saraleefoundation.org 2 Sara Lee Corporation 1998|1999 e at Sara Lee Corporation are fortunate to be part of a successful W enterprise that has ongoing profitable growth and loyal customers who enjoy our family of brands. -

National Companies Matching Grants

National Companies Matching Grants Check with your employer to determine whether they will match your contribution 3M Foundation Baxter Healthcare Abbott Laboratories Best Foods ACE USA Group BF Goodrich Aerospace ADP Black & Decker Corporation AETNA The Boeing Company AIG (American Intl Group) Bridgestone/Firestone Air Products and Chemicals Burlington Northern Santa Fe Alcoa Cable One Alliance Capital Management Cadence Allstate Carter-Wallace Altria/Phillip Morris Cendant Corp AMD/Adv. Micro Devices Charles Schwab Corp. Ameren Corporation Chevron/Texaco American Express Citgo Petroleum American Electric Power CitiGroup American International Group, Inc CAN (Insurance & Financial) American Standard Foundation Coca-Cola Company AON Corporation Compaq Computer APS ConocoPhillips Argonaut Group Costco ATMI Countrywide Financial AT&T Delta Air Lines Automatic Data Processing Inc. Dial Corp Auto Nation DirectTV Auto Owners Insurance Duetsche Bank/Alex Brown Avon Products Dunn & Bradstreet AXA Financial Dupont Bank of America Eli Lily & Company Bank One Enterprise Rent Car Bard Medical Equifax Barnes Group Equitable BAX Global ExxonMobil Fannie Mae L’eggs Farmers Group (Insurance) Lehman Brothers Investments FedEx Lockheed Martin First Data Lowes Home Improvements Follett Corporation Lojack Ford Foundation Macy’s West Fortune Brands March & McLennan Frito Lay Corporation MassMutual Financial Insurance Gannett MasterCard International Gap Stores May Company General Dynamics Maytag General Electric Mazda North America General Mills McDonald’s General Motors McKesson (Phoenix) Gillett company Medtronic Glaxo SmithKline Merrill Lynch Harcourt Met Life Harris Trust Microsoft Corporation Hewlett Packard Mitsubishi International Home Depot Mobil Retiree Program Honeywell Hometown Solutions Monsanto Household International Morgan Stanley IBM Motorola IKON Office Solutions Nabisco In-N-Out Burger National Computer Systems Intel Neiman Marcus Group International Paper Company Nokia ITW/Illinois Tool Works Northern Trust John Hancock Life Ins. -

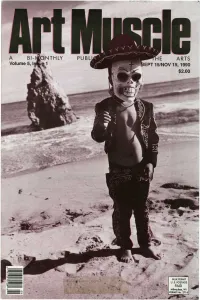

Art Muscle's Fourth Anniversary, Or, If Your Prefer, the Start Nathan Guequierre of Its Fifth Year

Editor-in-Chief Debra Brehmer Associate Editor Calendar Editor Business Manager Mary Therese Gantz Associate Editor-Music Bobby DuPah from t h e e d t o r Associate Editor This issue marks Art Muscle's fourth anniversary, or, if your prefer, the start Nathan Guequierre of its fifth year. Did I really just type that? It doesn't seem possible that we've been doing this for four years. What a significant chunk of time. (If s the longest job I've ever held). And although we've certainly had our trials, it Photo Editor remains fun. To reminisce just a bit—Art Muscle was launched without any Francis Ford investment money. We'd sell enough ads to pay for each issue, scrimping along, constantly worrying that we might not make it from issue to issue. Four Design years later, we don't worry quite as much. (For the first time in my life, I have Chris Bleiler fingernails on one hand. If s a start). We've surfaced from enough near- disasters to know that the magazine has acquired some durability. It won't just go away in the wake of an unsuccessful issue. The magazine has become Editorial Assistant an integral part of the art community. I would hate to see Milwaukee without Judith Ann Moriarty a solid, alternative vehicle for arts criticism. Arts coverage by the popular press in all cities is usually scant and we feel Art Muscle truly fills a void and Sales speaks to a unique audience. Lisa Mahan This upcoming fifth year will be a telling one.