Assessing the Strategic Evolution of U.S. Low-Cost Carriers in the Post-9/11 Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southwest Airlines 1996 Annual Report

1996 Annual Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Consolidated Highlights 2 Introduction 3 Letter to Shareholders 4 People and Planes 6 Southwest Spirit 8 THE Low Fare Airline 10 Productivity 12 Ontime Performance 14 Customer Satisfaction 16 Mintenance and Safety 18 What’s Next? 20 Financial Review 22 Management’s Discussion and Analysis 22 Consolidated Financial Statements 31 Report of Independent Auditors 49 Quarterly Financial Data 50 Common Stock Price Ranges and Dividends 50 Corporate Data 51 Directors and Officers 52 Ten Year Summary 55 CONSOLIDATED HIGHLIGHTS (DOLLARS IN THOUSANDS PERCENT EXCEPT PER SHARE AMOUNTS) 1996 1995 CHANGE Operating revenues $3,406,170 $2,872,751 18.6 Operating expenses $3,055,335 $2,559,220 19.4 Operating income $350,835 $313,531 11.9 Operating margin 10.3% 10.9% (0.6)pts. Net income $207,337 $182,626 13.5 Net margin 6.1% 6.4% (0.3)pts. Net income per common and common equivalent share $1.37 $1.23 11.4 Stockholders’ equity $1,648,312 $1,427,318 15.5 Return on average stockholders’ equity 13.5% 13.7% (0.2)pts. Debt as a percentage of invested capital 28.3% 31.7% (3.4)pts. Stockholders’ equity per common share outstanding $11.36 $9.91 14.6 Revenue passengers carried 49,621,504 44,785,573 10.8 Revenue passenger miles (RPMs)(000s) 27,083,483 23,327,804 16.1 Available seat miles (ASMs)(000s) 40,727,495 36,180,001 12.6 Passenger load factor 66.5% 64.5% 2.0 pts. Passenger revenue yield per RPM 12.07¢ 11.83¢ 2.0 Operating revenue yield per ASM 8.36¢ 7.94¢ 5.3 Operating expenses per ASM 7.50¢ 7.07¢ 6.1 Number of Employees at yearend 22,944 19,933 15.1 NET INCOME (in millions) $207 $179 $183 250 $154 200 $97 150 100 50 0 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 2 NET INCOME PER SHARE $1.37 $1.22 $1.23 1.40 $1.05 1.20 1.00 $.68 0.80 0.60 0.40 0.20 0.00 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 SOUTHWEST AIRLINES CO. -

David Neeleman

David Neeleman David Neeleman is that rarest of entrepreneurs, a man who has created and launched four successful, independent airlines, including the USA’s JetBlue and Morris Air, Canada’s WestJet and Brazil’s Azul. Azul, just seven years old, has already boarded tens of millions of customers. Born in Brazil while his father was Reuter’s São Paulo Bureau Chief, David has always had a deep love for the country. After his family moved to Utah while he was still a child, David would return to Brazil many times throughout his life. A dual citizen, David today relishes the dream before him to make flying cheaper and easier for Brazilians, giving access to air travel for many who have never experienced the opportunity before. Azul serves more than 100 destinations with an operating fleet of more than 140 aircraft, including Brazilian-built Embraer E-190 and E-195 jets, and ATR-72s. Just as JetBlue in the US before it, Azul is the first airline in Latin America to offer LiveTV inflight TV programming via satellite. It has been named Best Low Cost Airline in South America for the last five years at the Skytrax World Airline Awards. In June 2015, it was announced that the Gateway consortium, led by David, had won the bidding to acquire a stake in Portugal’s national carrier TAP. Gateway’s investment represents 50% of the airline. With the new investment, TAP is taking delivery of A330s and inaugurated new daily service from both Boston’s Logan airport and New York’s John F Kennedy International in June and July, respectively. -

Monthly Statistics Report

Monthly Statistics Report To: Tom Jones, Aviation Director; Tim O’Krongley, Deputy Director From: Brian Pratte, Air Service Administrator Copies: San Antonio Regional Stakeholders Subject: July 2016 Monthly Statistics Date: August 26, 2016 SUMMARY Calendar year-to-date (CYTD) traffic continued its growth, up 0.56%, representing a total of 5,003,408 total passengers. This represents the largest CYTD traffic on record through July, the first time the total passenger count has exceeded 5 million in the first seven months of the year. The San Antonio International Airport served 802,345 total passengers in July 2016, a slight decrease of (0.9%) when compared to July 2015. The decrease must be viewed in context. In July 2015, the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventist Church was held in San Antonio. This convention, one of the largest conventions to be held in San Antonio, brought an estimated 65,000 attendees. Approximately 60% (~78,000) of those conventioneers arrived and departed via air travel. If last year’s convention were excluded from the year over year comparison, total passengers would have increased approximately 8.7%. Domestic traffic for the month was up 0.5%, while international traffic experienced a decline of (17.5%). Again, context is important. The rate of decline in international passengers has decreased and is in line with the year-over-year reduction in capacity. In October 2015, Southwest Airlines opened their new international terminal at Houston Hobby Airport. In order to expand international service at Hobby, and to maximize the available slots into Mexico City (MEX), the SAT-MEX flight was negatively impacted and eliminated. -

Breeze Airways Announces Debut

UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL MAY 21, 2021 AT 8AM ET: Breeze Airways Announces Debut Service from 16 Cities including Tampa Bay, Charleston, Norfolk and New Orleans; 95% of New Breeze Routes are Without Existing Nonstop Service Today -- New “Low Fare, High Flex” Airline is David Neeleman’s Fifth Airline Start-up, 20 Years After JetBlue’s Launch -- Salt Lake City, UT (May 21, 2021) – Breeze Airways, the new “Seriously Nice” U.S. carrier from JetBlue founder David Neeleman, today unveiled its debut network, comprising 39 nonstop routes between 16 cities in the Southwest, Midwest, Southeast and Eastern US. The first flights will operate between Charleston, SC, Tampa, FL and Hartford, CT, starting May 27, with remaining destinations to be added each week through July 22, 2021. Flights are now on sale at www.flybreeze.com and the Breeze app, starting at just $39* one way. Breeze is Mr Neeleman’s fifth airline start-up, after JetBlue, Brazil’s Azul, Canada’s WestJet, and Utah-based Morris Air, which was later purchased by Southwest Airlines. Headquartered in Salt Lake City, UT, Breeze will focus most flights from four main airports: Tampa, FL; Charleston, SC; New Orleans, LA; and Norfolk, VA. Joined by an experienced team of industry veterans, Mr Neeleman set out to build an airline that offers a great experience, with low fares and high flexibility: “Together, we created Breeze as a new airline merging technology with kindness. Breeze provides nonstop service between underserved routes across the U.S. at affordable fares. A staggering 95 percent of Breeze routes currently have no airline serving them nonstop. -

Eastern Sierra Air Service Strategic Plan NOVEMBER 2017

Eastern Sierra Air Service Strategic Plan NOVEMBER 2017 Mammoth Lakes Contents 1 Introduction 1.1 6 Economic Impact Analysis 6.1 2 Industry Trends 2.1 7 Peer Review 7.1 3 Airport Characteristics 3.1 8 Next Steps 8.1 4 Existing Air Service 4.1 Appendix A: Glossary A.1 5 Air Service Opportunities 5.1 Eastern Sierra Air Service Strategic Plan Mammoth Lakes 1 Introduction As home to Mammoth Mountain and as the eastern gateway to Yosemite National Park, local, commercial air service is important in supporting the more than 1.6 million annual visitors. In addition, the business community and residents need local access to air service to avoid the more than three-hour drive from Reno-Tahoe International Airport, the closest alternate commercial service airport. While existing Alaska Airlines and United Airlines services are valued by the community, reliability issues have impacted use of local air service. Mammoth Lakes 1.1 The primary objective of the “Eastern Sierra Air Service Strategic Plan is to provide the information and recommendations necessary to guide air service development efforts over the next five to 10 years to achieve the air service goals. ” Air Service Goal Strategic Plan Objectives Local Partners The primary air service goal is to provide reliable, The primary objective of the Eastern Sierra Air Service Mammoth Lakes Tourism works in cooperation with the sustainable and successful air service to the Eastern Strategic Plan is to provide the information and Town of Mammoth Lakes to provide marketing and sales Sierra by growing existing air service via increasing flight recommendations necessary to guide air service promotion outreach for local, commercial air service. -

Redalyc.Engineering and Strategy: Returning to the Case of Southwest

Revista Escuela de Administración de Negocios ISSN: 0120-8160 [email protected] Universidad EAN Colombia Berrío Zapata, Cristian Engineering and strategy: returning to the case of southwest airlines, an analysis in production and technology management Revista Escuela de Administración de Negocios, núm. 73, julio-diciembre, 2012, pp. 209-217 Universidad EAN Bogóta, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=20625032013 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Casos empresariales ENGINEERING AND STRATEGY: RETURNING TO THE CASE OF SOUTHWEST AIRLINES, AN ANALYSIS IN PRODUCTION AND TECHNOLOGY MANAGEMENT Cristian Berrío Zapata 1. INTRODUCTION ome company cases let us see what was a network that makes every part of it shake, when any done to produce business model innovation component is touched. This network, immersed into Sthat creates ruptures in the market, changing the environment evolution, is a complete systemic the rules of competition. One of these cases is the unit, where paradigm changes must be supported with story of Southwest Airlines (SWA). This article tries to operational actions so innovation becomes a living demonstrate that engineering operational excellence is force that changes competing profiles. This virtuous fruitless without a compatible moving in other conceptual cycle between thought and action, when successful axes like service, finances, administration and human in producing adaptative and innovative competing resources. The areas of a company are bounded into structures, revolves the markets and generates new rules for competition. -

Southwest Airlines Celebrates 15 Years of Denver Service Southwest First Launched Flights from Denver International Airport on Jan

DEN Media Contact Southwest Media Contact Emily Williams Initial or breaking media inquiries: +01 (214) 792-7675 or [email protected] [email protected] 24/hr. Media Line: 720-583-5758 Visit the Southwest Newsroom at swamedia.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Southwest Airlines Celebrates 15 Years of Denver Service Southwest first launched flights from Denver International Airport on Jan. 3, 2006 DENVER – January 4, 2021 – Southwest Airlines celebrates 15 years of serving Denver International Airport (DEN) in 2021. The carrier inaugurated service in the Mile High City on Jan. 3, 2006, with 13 daily departures to three destinations – Chicago-Midway (MDW), Las Vegas (LAS) and Phoenix (PHX). Today Denver is the largest operation in the Southwest network, averaging 174 departures a day in 2020 and connecting Denver nonstop to more than 70 destinations in 36 U.S. states and Mexico. “For 15 years Southwest has been a great partner and we’re so pleased the airline continues to grow in Denver, offering nonstop service to more than 70 destinations,” said DEN CEO Kim Day. “We are grateful for Southwest’s commitment to DEN and look forward to many more successful years, including the opening of 16 new Southwest gates on Concourse C-East in 2022.” During the past 15 years, Southwest has carried more than 175 million passengers through DEN. Notably, Southwest is the largest carrier of domestic origination and destination (O&D) traffic in Denver. In 2020 alone, Southwest expanded its connectivity to Denver with the addition of seven new routes, including winter season service three times daily between Denver and both Steamboat Springs/Hayden and Montrose that began Dec. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE CONTACT: Investor Relations Corporate Communications 435.634.3200 435.634.3553 [email protected] [email protected] SkyWest, Inc. Reports Combined November 2017 Traffic for SkyWest Airlines and ExpressJet Airlines ST. GEORGE, UTAH, Dec. 11, 2017 -- SkyWest, Inc., (NASDAQ: SKYW) (“SkyWest”) today reported 144,180 block hours in November 2017, compared to 148,707 block hours in November 2016, a decrease of 4,527 or 3.0%. The net decrease was consistent with SkyWest’s fleet transition plan to improve the mix of aircraft in its fleet by adding new E175 aircraft, while reducing its 50-seat jets. The year-over-year net change was primarily driven by approximately 9,900 additional block hours from its E175 aircraft and a decrease of approximately 14,400 block hours from its other aircraft types. In November 2017, SkyWest’s dual class aircraft represented approximately 53% of SkyWest’s total block hour production for the month compared to approximately 44% for the month of November 2016. SkyWest reported 1,688,342 block hours for year-to-date November 2017, compared to 1,781,704 block hours year-to-date November 2016, a decrease of 93,362, or 5.2%. This net change was primarily driven by approximately 139,200 additional block hours from its E175 aircraft and a decrease of approximately 232,500 block hours from its other aircraft types. SkyWest had 84,151 departures in November 2017 compared to 88,485 in November 2016, a decrease of 4,334, or 4.9%. Additional flight statistics for November are included in the accompanying table. -

Biz Tips: Know Your End-Game Sunday, October 31, 2004 by Art Hill

BIZTIPS - October 31, 2004 Biz Tips: Know Your End-Game Sunday, October 31, 2004 By Art Hill Like the world champion Red Sox, you need a clear objective for your business when you start the season. You might not be setting out to win your first World Series in 86 years, but knowing your business objective can be just as important. Remember to “begin with the end in mind.” Whether your business is just forming or has sustained your family for generations, you need to think about your last day in business as well as your first. Take Morris Air for example. In 1984, David Neeleman and June Morris, then travel agency execs, started a modest charter airline in Salt Lake City. Some airlines had brightly painted planes and slogans like “Your Top Banana to Reno.” Others adopted a slightly older sales technique and cut flight attendant uniforms to fit the miniskirt craze. Neeleman and Morris were a bit more creative. They offered discount fares to undermine traditional (expensive) airlines in a city with explosive growth and an ideal location for popular west coast destinations. But the key to their long range success was their end-game plan. Using only Boeing 737 aircraft and adopting the highly successful “no frills” approach of Southwest Airlines, they built a company designed to be sold. In 1994 Southwest purchased its little look-alike for the tidy sum of $129 million. Morris Air had begun with the end in mind and ended on a note of stunning success. Not all businesses achieve the goals of their owners. -

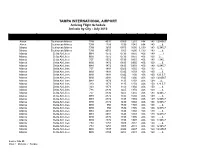

Flight-Schedule-Template

TAMPA INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT Arriving Flight Schedule Arrivals by City - July 2015 Departure Arrival Cities Served Airline Aircraft Flight No. Miles Seats Days Time Time Akron Southwest Airlines 73W 4531 0950 1210 894 143 1234567 Akron Southwest Airlines 73W 1108 1330 1545 894 143 .....6. Albany Southwest Airlines 73W 3650 0705 1005 1,130 143 12345.7 Albany Southwest Airlines 73W 4553 1305 1605 1,130 143 .....6. Atlanta Delta Air Lines M88 1572 0730 0850 406 149 ......7 Atlanta Delta Air Lines M90 1572 0730 0850 406 160 .2..... Atlanta Delta Air Lines 757 1572 0730 0850 406 183 1.345.. Atlanta Delta Air Lines M90 1472 0835 0956 406 160 .....6. Atlanta Delta Air Lines M88 1472 0835 0958 406 149 12345.7 Atlanta Delta Air Lines 757 1891 0925 1050 406 183 ...4... Atlanta Delta Air Lines M90 1891 0935 1059 406 160 .....6. Atlanta Delta Air Lines M90 1891 0935 1100 406 160 123.5.7 Atlanta Delta Air Lines M90 2091 1035 1200 406 160 1234567 Atlanta Delta Air Lines M88 1373 1135 1258 406 149 ...4... Atlanta Delta Air Lines 320 1373 1135 1258 406 150 123.5.7 Atlanta Delta Air Lines 320 1373 1140 1302 406 150 .....6. Atlanta Delta Air Lines 738 2330 1225 1350 406 160 .....6. Atlanta Delta Air Lines 757 2330 1225 1350 406 183 12345.7 Atlanta Delta Air Lines M88 2372 1335 1502 406 149 .....6. Atlanta Delta Air Lines M88 2372 1335 1504 406 149 12345.7 Atlanta Delta Air Lines M90 2172 1430 1602 406 160 12345.7 Atlanta Delta Air Lines M90 950 1530 1703 406 160 .....6. -

Massachusetts Institute of Technology Flight Transportation Laboratory

Massachusetts Institute of Technology Flight Transportation Laboratory Report FTL-R79-5 A SYSTEMS ANALYSIS OF SCHEDULED AIR TRANSPORTATION NETWORKS William M. Swan June 1979 FLIGHT TRANSPORTATION LABORATORY REPORT R79-5 A SYSTEM ANALYSIS OF SCHEDULED AIR TRANSPORTATION NETWORKS BY: WILLIAM M. SWAN - 1" 11 M- - ABSTRACT This work establishes the conditions for airline system design building from submodels of smaller aspects of air transportation. The first three sections develop submodels which then are combined in extensive numerical studies of singles market services. The final section discusses the changes to this problem that occur due to network effects. The first section develops a simple model of the cost of providing scheduled transportation on a link. The cost of aircraft of various capacities are divided into a per-frequency cost and a per-capacity cost for conventional subsonic turbojet designs. This cost structure implies that the more capacity provided in conjunction with a fixed schedule of departures the lower the average cost per seat. It is suggested that such aircraft scale economies create a trend toward monopoly or at least oligopoly services. The second section develops a model for demand. The market for transportation is argued to be the city pair. Demand for scheduled service is expressed in terms of fare, frequency and load factor. Fare, frequency, and load factor are combined into total perceived price for the service. This price depends on the consumer's personal value of time. With only a few competitors in aich a market, only a few of the tech- nically possible qualities of service will be offered. -

November 2015 Newsletter

PilotsPROUDLY For C ELEBRATINGKids Organization 32 YEARS! Pilots For KidsSM ORGANIZATION Helping Hospitalized Children Since 1983 Want to join in this year’s holiday visits? Newsletter November 2015 See pages 8-9 to contact the coordinator in your area! PFK volunteers from ORF made their first visit to the Children’s Hospital of the King’s Daughters (CHKD). This group from Delta/VFC-12 and UAL enjoyed their inaugural visit in October and volunteers plan more visits through the holiday season. “100% of our donations go to the kids” visit us at: pilotsforkids.org (2) (3) Pilots For Kids Organization Pilots For Kids Organization President’s Corner... More Success for Dear Members, MCO Golf According to Webster’s Dictionary, the Captain Baldy was joined by an enthusiastic group of definition of fortunate is “bringing some good not golfers at Rio Pinar Country Club in Orlando on Sat- foreseen.” urday, October 24th. The golf event was followed by lunch and a silent auction that raised additional funds Considering that definition, our organization for Orlando area children. is indeed fortunate on many levels. We are fortu- nate to have members who passionately support Special thanks to all of the businesses who donated our vision, financially support our work, and vol- to make the auction a huge success. The group of unteer their valuable time to benefit hospitalized generous doners included the Orlando Magic, Jet- children. Blue, Flight Safety, SeaWorld/Aquatica, i-FLY, Embassy Suites, Hyatt Regency, Wingate, Double- Because of this good fortune, we stand out tree, Renaissance, Sonesta Suites, LaQuinta, the among many creditable charitable organizations.