Evolution of the Iron–Silicate and Carbon Material of Carbonaceous Chondrites A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 1998 Gems & Gemology

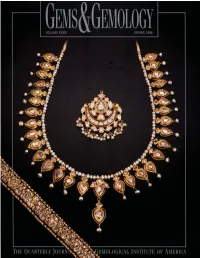

VOLUME 34 NO. 1 SPRING 1998 TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITORIAL 1 The Dr. Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award FEATURE ARTICLE 4 The Rise to pProminence of the Modern Diamond Cutting Industry in India Menahem Sevdermish, Alan R. Miciak, and Alfred A. Levinson pg. 7 NOTES AND NEW TECHNIQUES 24 Leigha: The Creation of a Three-Dimensional Intarsia Sculpture Arthur Lee Anderson 34 Russian Synthetic Pink Quartz Vladimir S. Balitsky, Irina B. Makhina, Vadim I. Prygov, Anatolii A. Mar’in, Alexandr G. Emel’chenko, Emmanuel Fritsch, Shane F. McClure, Lu Taijing, Dino DeGhionno, John I. Koivula, and James E. Shigley REGULAR FEATURES pg. 30 44 Gem Trade Lab Notes 50 Gem News 64 Gems & Gemology Challenge 66 Book Reviews 68 Gemological Abstracts ABOUT THE COVER: Over the past 30 years, India has emerged as the dominant sup- plier of small cut diamonds for the world market. Today, nearly 70% by weight of the diamonds polished worldwide come from India. The feature article in this issue discuss- es India’s near-monopoly of the cut diamond industry, and reviews India’s impact on the worldwide diamond trade. The availability of an enormous amount of small, low-cost pg. 42 Indian diamonds has recently spawned a growing jewelry manufacturing sector in India. However, the Indian diamond jewelery–making tradition has been around much longer, pg. 46 as shown by the 19th century necklace (39.0 cm long), pendant (4.5 cm high), and bracelet (17.5 cm long) on the cover. The necklace contains 31 table-cut diamond panels, with enamels and freshwater pearls. -

Lindsey Prewitt,Moissanite –

Feature Friday – Lindsey Prewitt I was looking for a job when someone told me Stuller was having a career fair. I went and met with a few people from marketing then I applied for a position as a Loyalty Program Manager. I landed an interview and clearly remember the interesting question asked on my way out: If I were the Public Relations person for Jeep and their vehicles’ gas tanks began exploding, what would I do to keep customers coming back? I was asked to send my response via email in the next few days. So I got online and researched everything from Jeep loyalty to gas tank explosions! I even called my uncle, a mechanic, to talk through the design aspects of automobiles and gain a better understanding of the “issue” at hand. I typed up my report and sent it to my interviewers. I suppose I left a lasting impression because they told me I’d be a great fit for a different position within the company. That’s when I met with Stanley Zale and the gemstone team. I started working here in May of 2015. Lindsey with a customer at JCK Las Vegas Here I am a year and a half down the road, and I still feel grateful for the wonderful opportunity. I am a Gemstone Product Manager. Many know me as the Moissanite Lady as well, but I’m in charge of all the brands:Charles and Colvard Moissanite, Chatham, and Swarovski, plus imitations and synthetics. I have a hand in everything associated with these gemstones, from marketing on the web and in print, facilitating customer interaction atBridge , tradeshows, Transform Tours, etc. -

Downloaded 9/27/2021 10:18:48 AM

JAAS TUTORIAL REVIEW View Article Online View Journal | View Issue Isotopes in cosmochemistry: recipe for a Solar System Cite this: J. Anal. At. Spectrom.,2016, 31, 841 Steven Goderis,*ab Ramananda Chakrabarti,c Vinciane Debailled e and Janos´ Kodolanyi´ Extreme isotopic variations among extraterrestrial materials provide great insights into the origin and evolution of the Solar System. In this tutorial review, we summarize how the measurement of isotope ratios can expand our knowledge of the processes that took place before and during the formation of our Solar System and its subsequent early evolution. The continuous improvement of mass spectrometers with high precision and increased spatial resolution, including secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS), thermal ionization mass spectrometry (TIMS) and multi collector-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (MC-ICP-MS), along with the ever growing amounts of available extraterrestrial samples have significantly increased the temporal and spatial constraints on the sequence of events that took place since and before the formation of the first Solar System condensates (i.e.,Ca– Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported Licence. Al-rich inclusions). Grains sampling distinct stellar environments with a wide range of isotopic compositions were admixed to, but possibly not fully homogenized in, the Sun's parent molecular cloud or the nascent Solar System. Before, during and after accretion of the nebula, as well as the formation and subsequent evolution of planetesimals and -

Natural Moissanite Properties and Terrestrial Occurrence Griffin, W

B"H Natural Moissanite Properties and Terrestrial Occurrence Griffin, W. L. (1), Toledo, V. (2), Gain, S.E.M. (1), Huang, J-X. (1) 1. ARC Centre of Excellence for Core to Crust Fluid Systems and GEMOC, Macquarie University, NSW 2109, Australia 2. Shefa Yamim (A.T.M.) Ltd., Akko, Israel Composition: Silicon Carbide (SiC). Silicon 70%, Carbon 30% by weight. Crystal Structure Hexagonal - Dihexagonal Pyramidal H-M Symbol (6mm) Space Group: P 63mc Properties Cleavage: {0001} Indistinct Color: Blue, Colorless, Green, Green yellow, Yellow. Density: 3.218 - 3.22, Average = 3.21 Diaphaneity: Transparent to Opaque Fracture: Conchoidal - Fractures developed in brittle materials characterized by smoothly curving surfaces, (e.g. quartz). Habit: Usually microscopic crystals, hexagonal plates Hardness: 9.5 - Silicon Carbide Luster: Metallic Refractive index: 2.691-2.648; slightly higher than diamond (2.42) Streak: greenish gray Dichroism (e): weak blue. Dichroism (w): weaker blue. Optical Data: Uniaxial (+), w=2.654, e=2.967, bire=0.3130. The historical background of Moissanite and of Charles & Colvard that, if properly cut, the its use as a gemstone crystals could make a beautiful jewel. Charles & Colvard recognized the mineral's potential. In 1893, the Nobel Prize-winning French They also realized that in order for the scientist Dr. Henri Moissan discovered minute moissanite gems to be used, they would have quantities of a new mineral, natural silicon to be manufactured, since there is essentially carbide. The mineral was discovered in an iron no natural supply for this stone. In 1995, meteorite (Canyon Diablo) in Arizona. It was Charles & Colvard collaborated with Cree to later named "moissanite" in honor of Dr. -

T£OR CRATER ARJZQNA 5Ery'ic& JTTE€0AIL, RJEPOIRJT

JTTE€0AIL, RJEPOIRJT MO. -2\ > !£T£OR CRATER ARJZQNA 8Y VINCENT W VANDIVER DEPARTMENT OF THE.- IHTERIOf^ HATiOHAL PARJC 5eRy'ic& JM£J£OR GRATER, ARJXOJNA By Vincent W. Vandiver, Associate Regional Geologist. INTRODUCTION It is the purpose of this report to summarize some of the various theories which have been advanced, during the past 35 years, to account for the origin of Meteor Crater. To outline some of my observations re garding this phenomena of nature which has attracted scientists fron all parts of the earth for many years. Efforts to exploit the meteoric mass by commercial interests in which large sums of money have been expended will be noted. Briefly it is proposed to bring up to date our present knowledge of Meteor Crater for the Park ServicG records and the possible interest for various members of the staff concerned. The noted Astronomer, Arrhsnius, is said to have declared that Meteor Crater is the most fascinating spot on earth. The interesting fields for investigation in this area are innumerable. Facts may be disclosed which to an astronomer might give concrete evidence as to our theories of origin and the building up of our solar system. Should the crater be definitely proven the result of a meteoric impact, the. geologist will be interested to have the evidence to be found in the behavior of rocks under sudden stress, not to mention the later effects of chemical reactions underground. From the point of view of the physicist and chemist the various features prove none the less interesting. The average visitor stands in amazement when the great pit is viewed from the rim for the first time. -

Download the Scanned

TH n A MERlcelt M IN ERALocIST JOURNAL OF THE MINERALOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA Yol.26 MARCH, 1941 No.3 PROBLEMS IN THE STUDY OF METEORITES*I W. F. Fosnec, Curator, Mineralogy and.Petrologt, (I . S. National Museurn, Washington,D.C. INrnorucuoN The fall of meteorites from heaven has been a recognizedphenomenon for many centuries. It is stated that the first record is one among the Chinese 6,000 years ago. The Persians, Greeks and Romans considered them as messagesfrom the Gods, built temples over them and revered them. During the Middle Ages they were looked upon as omens of evil, bewitched personagesand similar prodigies. Later, a belief in the possibility of stones fallen from heaven brought forth only ridicule, gven from scientific men. Stiitz, a famous Austrian mineralogist, remarked, concerning the reported fall of a mass of pure iron at Agram in 1751,that "in our times it would be unpardonableto considersuch fairy tales even probable." The German physicist, Chladni, in 1794first challenged this disbelief and even suggestedthat meteorites are, in fact, "world fragments." Mineralogists now recognizedthem for what they are-celestial rocks-rocks with many unusual characters, but amenable to study by the same methods as the better known ter- restrial rocks. The earliestpreserved meteorite is one that fell at Ensisheim,Germany, on November 16, 1492.Since then 1,250 distinct meteoriteshave been recovered,some only as a small individual of but a few grams, others very much larger, even weighing tons. Some reach the earth in thousands of fragments as a shower of stonesduring a single fall, as those of Pultusk in 1868, when 100,000fragments are said to have fallen. -

MOISSANITE ENGAGEMENT RING GUIDE Welcome to a World Made Brighter with Moissanite

MOISSANITE ENGAGEMENT RING GUIDE Welcome to a World made brighter with moissanite At MoissaniteBridal.com, we understand the level of commitment and thoughtful research that comes with choosing the right engagement ring. That’s why we created our new Moissanite Engagement Ring Guide™. This invaluable resource provides you with essential insight into the vast world of engagement and wedding jewelry; conflict-free diamonds; sustainable materials, like recycled gold; and diamond alternatives, including Charles & Colvard® moissanite. We hope you’ll find this guide helpful in your decision-making process. Like Charles & Colvard, MoissaniteBridal.com proudly stands behind our moissanite jewels and guarantees that each one will maintain its fire and brilliance, without fading or changing color. If you have any questions about moissanite wedding jewelry, please visit us at www.MoissaniteBridal.com today. ©2015 MoissaniteBridal.com Call toll-free 1-888-345-8725 (US) Contact [email protected] www.MoissaniteBridal.com 2 ©2015 MoissaniteBridal.com Call toll-free 1-888-345-8725 (US) Contact [email protected] www.MoissaniteBridal.com 3 Table of Contents p 5 Who Discovered Moissanite? p 6 A Brief History of Moissanite p 7 14k Gold, Platinum and Palladium p 8 More About Conflict Diamonds p 9 The Five Cs of Moissanite p 11 Anatomy of a Moissanite and Diamond p 12 Popular Cuts of Moissanite p 13 Cuts and Weights of Moissanite p 17 Moissanite vs. Diamond p 18 Moissanite vs. CZ p 19 Commonly Marketed Jewels p 20 Integrity, Trust and Quality p 21 DesignYour Own Engagement Ring ©2015 MoissaniteBridal.com Call toll-free 1-888-345-8725 (US) Contact [email protected] www.MoissaniteBridal.com 4 Who Discovered Moissanite? FERDINAND FREDERIC HENRI MOISSAN as found in the journal of Gems & Gemology, 1999 Henri Moissan was born in Paris on September 28, 1852. -

The Proposed Nalbach (Saarland, Germany) Impact Site: Is It a Companion to the Chiemgau (Southeast Bavaria, Germany) Impact Stre

THE PROPOSED NALBACH (SAARLAND, GERMANY) IMPACT SITE: IS IT A COMPANION TO THE 76th Annual Meteoritical CHIEMGAU (SOUTHEAST BAVARIA, GERMANY) IMPACT STREWN FIELD? Society Meeting (2013) 5058.pdf Abstract Nalbach and Chiemgau parallels, cont. Observations, cont. (Figs. 10 - 18) Widespread occurrence of peculiar Kord Ernstson samples in the Nalbach area (Saarland, Faculty of Philosophy I, University of West of Germany) covering many Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany, square kilometers makes a meteorite [email protected] impact event in the Holocene very probable. Most convincing are Fig. 21. Very dense and hard glassy carbon. Werner Müller indications of high temperatures and In the Chiemgau impact event this glass-like 66809 Nalbach, Germany high pressures and the evidence of Fig. 10. Polymictic Fig. 11. Melt rock with monogenetic rock Fig. 12. Melt rock with carbon is suggested to be an end product in an [email protected] probable shock. Absolutely identical breccia with rock particles (quartzite) in a glass matrix. Cut polygenetic rock particles in a impact shock-produced short-term and glass particles surface. glass matrix. coalification process the target vegetation findings in the Chiemgau meteorite in a dominantly (wood, peat) having been the source material. impact crater strewn field suggest that sandy matrix. The Millimeter scales. Andreas Neumair obviously most similar processes at a aligned reddish Institute for Interdisciplinary Studies, glass fragments Gilching, Germany, related time took place. A coincidence may point to flow provided, an extended impact event texture. [email protected] that affected a distance of at least 500 km must be considered. Fig. 1 Fig. 14. Quartz grain from a breccia sandstone particle on grain slide Fig. -

SEM and TEM Analyses of Minerals Xifengite, Gupeiite, Fe2si (Hapkeite

42nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2011) 1391.pdf SEM and TEM analyses of minerals xifengite, gupeiite, Fe2Si (hapkeite?), titanium carbide (TiC) and cubic moissanite (SiC) from the subsoil in the Alpine Foreland: Are they cosmochemical? M. Hiltl1, F. Bauer2, K. Ernstson3, W. Mayer4, A. Neumair4, and M.A. Rappenglück4 1Carl Zeiss Nano Technology Systems GmbH, Oberkochen, Germany ([email protected]), 2Oxford Instruments GmbH NanoScience, Wiesbaden, Germany ([email protected]), 3University of Würzburg, Germany ([email protected]), 4Institute for Interdiscipli- nary Studies, Gilching, Germany ([email protected], [email protected], [email protected]) Introduction: In the early 2000s when a group of broad. The size of the particles ranges between the local history researchers was licenced to practice metal order of a millimeter and a few centimeters. The sur- detector probing for archeological objects they repeat- faces show metallic luster and lack practically any cor- edly encountered millimeter to centimeter-sized parti- rosion. In many cases, a regmaglyptic surface resem- cles in the subsoil down to the substratum that proved bling ablation features of meteorites is striking (Fig. 1). Frequently, sparkling crystals can be seen with the to be iron silicides Fe3Si, mineral gupeiite, and Fe5Si3, mineral xifengite, completely unknown in the rural naked eye to stick out from the metallic matrix (Fig. districts of the Alpine Foreland. They suggested a pos- 2). sible meteoritic origin, and a few papers [1, 2, 3] seized on that idea, especially with regard to strongly restricted terrestrial formation of gupeiite and xifengite and their occurrences in cosmic globular particles from the Yanshan area in China [4]. -

The Structure of Canyon Diablo "Diamonds"

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/252295522 The Structure of Canyon Diablo "Diamonds" Article · March 2009 CITATIONS READS 5 521 2 authors: Laurence AJ Garvie Pèter Nèmeth Arizona State University Hungarian Academy of Sciences 164 PUBLICATIONS 3,712 CITATIONS 88 PUBLICATIONS 1,001 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: amorphous calcium carbonate View project Asteroid Robotics and In-situ Resource Utilization View project All content following this page was uploaded by Laurence AJ Garvie on 04 December 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. 40th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2009) 1346.pdf THE STRUCTURE OF CANYON DIABLO “DIAMONDS”. Laurence A.J. Garvie, Center for Meteorite Stud- ies, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona 85287-1404, USA, [email protected], Péter Németh, Department of Surface Modifications and Nanostructures, Chemical Research Center of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, H- 1025 Budapest, Pusztaszeri út 59-67, Hungary. Introduction: The first reports of “hard particles” Many of the larger grains show a crude layering. The in the Canyon Diablo meteorite dates to 1891 [1], and luster and roundness varies between grains. The less they were identified as diamond by X-ray diffraction in lustrous grains are softer and have a more graphitic 1939 [2]. More recent X-ray diffraction studies showed appearance. that the Canyon Diablo “diamonds” are composed of X-ray diffraction. The powder X-ray pattern shows various proportions of diamond, lonsdaleite, and a series of broad reflections with d-spacings that match graphite [2, 3]. -

Moissanite (Sic) from Kimberlites: Polytypes, Trace Elements, Inclusions and Speculations on Origin

Lithos 122 (2011) 152–164 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Lithos journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/lithos Moissanite (SiC) from kimberlites: Polytypes, trace elements, inclusions and speculations on origin A.A. Shiryaev a,⁎, W.L. Griffin b, E. Stoyanov c a Institute of Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry RAS, Leninsky pr. 31, Moscow 119991, Russia b GEMOC ARC Key Centre, Macquarie University, NSW 2109, Australia c Peter A. Rock Thermochemistry Laboratory and NEAT ORU, University of California at Davis, Davis, CA 95616, USA article info abstract Article history: An extensive collection of moissanite (SiC) grains from the Mir, Aikhal and Udachnaya kimberlite pipes of Received 26 July 2010 Yakutia has been characterized in terms of structural perfection, defects and the major- and trace-element Accepted 24 December 2010 chemistry of SiC and its included phases. The natural grains are clearly distinct from synthetic SiC produced by Available online 1 January 2011 various methods. Most of the natural SiC grains are 6H and 15R polytypes. Some of the grains (b10%) show extremely complex Raman spectra indicating strongly disordered structures. Some grains also show zoning in Keywords: impurities, C-isotope composition and cathodoluminescence brightness. Moissanite (SiC) Iron silicide Inclusions are heterogeneously distributed within the natural SiC; their size varies from a few nanometers to – – Oxycarbide hundreds of microns. The most abundant inclusions in SiC are Si metal and iron silicide (FeSi2); a Si C O Raman spectroscopy phase with stoichiometry close to Si4(C,O)7 probably is related to the silicon oxycarbides. FeSi2 commonly LAM-ICP-MS appears to have exsolved from Si metal; in some cases Ti metal then has exsolved from FeSi2 to form Electrochemical deposition symplectites. -

Moissanite: the Second Hardest Mineral in Nature After Diamond

MOISSANITE: THE SECOND HARDEST MINERAL IN NATURE AFTER DIAMOND The colors seen in moissanite from the Mount Carmel area of northern Israel range from dark blue to light green. Formula: SiC System: Hexagonal Colour: Green, black, Blue, Colorless, Green yellow, Yellow Lustre: Vitreous Hardness: 9½ Moissanite is the name given to naturally occurring silicon carbide and to its various crystalline polymorphs. It has the chemical formula SiC and is a rare mineral, discovered by the French chemist Henri Moissan in 1893. Silicon carbide is useful for commercial and industrial applications due to its hardness, optical properties and thermal conductivity. Mineral moissanite was discovered by Henri Moissan while examining rock samples from a meteor crater located in Canyon Diablo, Arizona, in 1893. At first, he mistakenly identified the crystals as diamonds, but in 1904 he identified the crystals as silicon carbide. The mineral was named in his honour. The mineral form of silicon carbide was named moissanite in honor of Moissan later on in his life. The discovery in the Canyon Diablo meteorite and other places was challenged for a long time as carborundum contamination from man-made abrasive tools. Geology: Moissanite, in its natural form, is very rare. It has only been discovered in a small variety of places from upper mantle rock to meteorites. Discoveries have shown that moissanite occurs naturally as inclusions in diamonds, xenoliths, and ultramafic rocks such as kimberlite and lamproite. They have also been identified in carbonaceous chondrite meteorites as presolar grains. The colors seen in moissanite from the Mount Carmel area of northern Israel range from dark blue to light green.