The Structure of Canyon Diablo "Diamonds"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Handbook of Iron Meteorites, Volume 3

Sierra Blanca - Sierra Gorda 1119 ing that created an incipient recrystallization and a few COLLECTIONS other anomalous features in Sierra Blanca. Washington (17 .3 kg), Ferry Building, San Francisco (about 7 kg), Chicago (550 g), New York (315 g), Ann Arbor (165 g). The original mass evidently weighed at least Sierra Gorda, Antofagasta, Chile 26 kg. 22°54's, 69°21 'w Hexahedrite, H. Single crystal larger than 14 em. Decorated Neu DESCRIPTION mann bands. HV 205± 15. According to Roy S. Clarke (personal communication) Group IIA . 5.48% Ni, 0.5 3% Co, 0.23% P, 61 ppm Ga, 170 ppm Ge, the main mass now weighs 16.3 kg and measures 22 x 15 x 43 ppm Ir. 13 em. A large end piece of 7 kg and several slices have been removed, leaving a cut surface of 17 x 10 em. The mass has HISTORY a relatively smooth domed surface (22 x 15 em) overlying a A mass was found at the coordinates given above, on concave surface with irregular depressions, from a few em the railway between Calama and Antofagasta, close to to 8 em in length. There is a series of what appears to be Sierra Gorda, the location of a silver mine (E.P. Henderson chisel marks around the center of the domed surface over 1939; as quoted by Hey 1966: 448). Henderson (1941a) an area of 6 x 7 em. Other small areas on the edges of the gave slightly different coordinates and an analysis; but since specimen could also be the result of hammering; but the he assumed Sierra Gorda to be just another of the North damage is only superficial, and artificial reheating has not Chilean hexahedrites, no further description was given. -

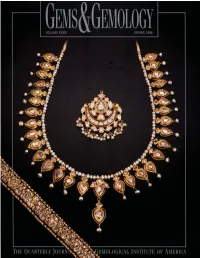

Spring 1998 Gems & Gemology

VOLUME 34 NO. 1 SPRING 1998 TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITORIAL 1 The Dr. Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award FEATURE ARTICLE 4 The Rise to pProminence of the Modern Diamond Cutting Industry in India Menahem Sevdermish, Alan R. Miciak, and Alfred A. Levinson pg. 7 NOTES AND NEW TECHNIQUES 24 Leigha: The Creation of a Three-Dimensional Intarsia Sculpture Arthur Lee Anderson 34 Russian Synthetic Pink Quartz Vladimir S. Balitsky, Irina B. Makhina, Vadim I. Prygov, Anatolii A. Mar’in, Alexandr G. Emel’chenko, Emmanuel Fritsch, Shane F. McClure, Lu Taijing, Dino DeGhionno, John I. Koivula, and James E. Shigley REGULAR FEATURES pg. 30 44 Gem Trade Lab Notes 50 Gem News 64 Gems & Gemology Challenge 66 Book Reviews 68 Gemological Abstracts ABOUT THE COVER: Over the past 30 years, India has emerged as the dominant sup- plier of small cut diamonds for the world market. Today, nearly 70% by weight of the diamonds polished worldwide come from India. The feature article in this issue discuss- es India’s near-monopoly of the cut diamond industry, and reviews India’s impact on the worldwide diamond trade. The availability of an enormous amount of small, low-cost pg. 42 Indian diamonds has recently spawned a growing jewelry manufacturing sector in India. However, the Indian diamond jewelery–making tradition has been around much longer, pg. 46 as shown by the 19th century necklace (39.0 cm long), pendant (4.5 cm high), and bracelet (17.5 cm long) on the cover. The necklace contains 31 table-cut diamond panels, with enamels and freshwater pearls. -

Sulfide/Silicate Melt Partitioning During Enstatite Chondrite Melting

61st Annual Meteoritical Society Meeting 5255.pdf SULFIDE/SILICATE MELT PARTITIONING DURING ENSTATITE CHONDRITE MELTING. C. Floss1, R. A. Fogel2, G. Crozaz1, M. Weisberg2, and M. Prinz2, 1McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences and Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Washington University, St. Louis MO 63130, USA ([email protected]), 2American Museum of Natural History, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, New York NY 10024, USA. Introduction: Aubrites are igneous rocks thought (present only in CaS-saturated charges) has a flat REE to have formed from an enstatite chondrite-like pattern with abundances of about 0.5 x CI. precursor [1]. Yet their origin remains poorly Discussion: Oldhamite/glass D values are close to understood, at least partly because of confusion over 1 for most REE, consistent with previous results the role played by sulfides, particularly oldhamite. [4,5,6], and significantly lower than those expected CaS in aubrites contains high rare earth element based on REE abundances in aubritic oldhamite. In (REE) abundances and exhibits a variety of patterns contrast, D values for FeS are surprisingly high (from [2] that reflect, to some extent, those seen in about 0.1 to 1), given the low REE abundances of oldhamite from enstatite chondrites [3]. However, natural troilite. FeS/silicate partition coefficients experimental work suggests that CaS/silicate melt reported by [5] are somewhat lower, but exhibit a REE partition coefficients are too low to account for similar pattern. Alkali loss from the charges, the high abundances observed [4,5] and do not explain resulting in Ca-enriched glass, might provide a partial the variable patterns. -

Evolution of the Iron–Silicate and Carbon Material of Carbonaceous Chondrites A

ISSN 01458752, Moscow University Geology Bulletin, 2013, Vol. 68, No. 5, pp. 265–281. © Allerton Press, Inc., 2013. Original Russian Text © A.A. Marakushev, L.I. Glazovskaya, S.A. Marakushev, 2013, published in Vestnik Moskovskogo Universiteta. Geologiya, 2013, No. 5, pp. 3–17. Evolution of the Iron–Silicate and Carbon Material of Carbonaceous Chondrites A. A. Marakusheva, L. I. Glazovskayab, and S. A. Marakushevc aInstitute of Experimental Mineralogy, Russian Academy of Sciences, Chernogolovka, Moscow oblast, 142432 Russia email: [email protected] bFaculty of Geology, Moscow State University, Moscow, 119234 Russia email: [email protected] cInstitute of Problems of Chemical Physics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Chernogolovka, Moscow oblast, 142432 Russia email: [email protected] Received February 18, 2013 Abstract—The observed consistence of the composition of chondrules and the matrix in chondrites is explained by their origin as a result of chondrule–matrix splitting of the material of primitive (not layered) planets. According to the composition of chondrites, two main stages in the evolution of chondritic planets (silicate–metallic and olivine) are distinguished. Chondritic planets of the silicate–metallic stage were ana logs of chondritic planets, whose layering resulted in the formation of the terrestrial planets. The iron–silicate evolution of chondritic matter is correlated with the evolution of carbon material in the following sequence: diamond ± moissanite → hydrocarbons → primitive organic compounds. Keywords: meteorite matter, carbonaceous chondrites, hydrocarbons DOI: 10.3103/S0145875213050074 INTRODUCTION 2003) in star–planet systems that are similar to the solar system, in which nearstar giant planets were still The occurrence of diamond in a stable paragenesis preserved and are distinguished under the name rapid with moissanite (SiC) in an ironrich matrix is a char Jupiters. -

Lunar and Planetary Science XXX 1753.Pdf

Lunar and Planetary Science XXX 1753.pdf INTERSTELLAR DIAMOND. II. GROWTH AND IDENTIFICATION. Andrew W. Phelps, University of Dayton Research Institute, Materials Engineering Division (300 College Park, Dayton OH, 45469-0130, [email protected]). likely form clumps of carbon that look much like the Introduction: The first abstract in this series starting material – hydrogen rich sp3 bound clusters. suggested that many types of diamond are found in many types of meteoritic material and that the The compounds that fit the requirements above variation in polytype abundance appears to reflect the include the cycloalkanes such as adamantane [21-30] nature of the host. How the diamonds got there and (C10H16) and bicyclooctane (C6H8) (BCO) . what they mean will now be examined. Opinions These compounds ‘look’ like small cubic diamonds regarding the formation mechanism(s) of meteoritic and lonsdaleite respectively. If these particular and interstellar diamond grains have changed over compounds are suggested as models for diamond the years as new methods of making synthetic nuclei then a number of structural and diamond were developed[1,2]. Meteoritic diamonds thermodynamic predictions can be made about the were once believed to be the result of high pressure - types of diamond that can form and its relative temperature processes in the interior of planetary abundance with regard to the physics and chemistry bodies[3,4]. Impact formation of diamond became of its growth environment. A few examples of this popular after the development of shock wave are: Adamantane is a lower energy form and would diamond synthesis[5] because shock synthesis was tend to form in an environment of sufficient thermal able to form lonsdaleite and meteorites were full of energy to allow the molecule to organize into this lonsdaleite. -

Meteorites from the Lut Desert (Iran)

Meteorites from the Lut Desert (Iran) Hamed Pourkhorsandi, Jérôme Gattacceca, Pierre Rochette, Massimo d’Orazio, Hojat Kamali, Roberto Avillez, Sonia Letichevsky, Morteza Djamali, Hassan Mirnejad, Vinciane Debaille, et al. To cite this version: Hamed Pourkhorsandi, Jérôme Gattacceca, Pierre Rochette, Massimo d’Orazio, Hojat Kamali, et al.. Meteorites from the Lut Desert (Iran). Meteoritics and Planetary Science, Wiley, 2019, 54 (8), pp.1737-1763. 10.1111/maps.13311. hal-02144596 HAL Id: hal-02144596 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02144596 Submitted on 31 May 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - ShareAlike| 4.0 International License doi: 10.1111/maps.13311 Meteorites from the Lut Desert (Iran) Hamed POURKHORSANDI 1,2*,Jerome^ GATTACCECA 1, Pierre ROCHETTE 1, Massimo D’ORAZIO3, Hojat KAMALI4, Roberto de AVILLEZ5, Sonia LETICHEVSKY5, Morteza DJAMALI6, Hassan MIRNEJAD7, Vinciane DEBAILLE2, and A. J. Timothy JULL8 1Aix Marseille Universite, CNRS, IRD, Coll France, INRA, CEREGE, Aix-en-Provence, France 2Laboratoire G-Time, Universite Libre de Bruxelles, CP 160/02, 50, Av. F.D. Roosevelt, 1050 Brussels, Belgium 3Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Universita di Pisa, Via S. -

Impact−Cosmic−Metasomatic Origin of Microdiamonds from Kumdy−Kol Deposit, Kokchetav Massiv, N

11th International Kimberlite Conference Extended Abstract No. 11IKC-4506, 2017 Impact−Cosmic−Metasomatic Origin of Microdiamonds from Kumdy−Kol Deposit, Kokchetav Massiv, N. Kazakhstan L. I. Tretiakova1 and A. M. Lyukhin2 1St. Petersburg Branch Russian Mineralogical Society. RUSSIA, [email protected] 2Institute of remote ore prognosis, Moscow, RUSSIA, [email protected] Introduction Any collision extraterrestrial body and the Earth had left behind the “signature” on the Earth’s surface. We are examining a lot of signatures of an event caused Kumdy-Kol diamond-bearing deposit formation, best- known as “metamorphic” diamond locality among numerous UHP terrains around the world. We are offering new impact-cosmic-metasomatic genesis of this deposit and diamond origin provoked by impact event followed prograde and retrograde metamorphism with metasomatic alterations of collision area rocks that have been caused of diamond nucleation, growth and preserve. Brief geology of Kumdy-Kol diamond-bearing deposit Kumdy-Kol diamond-bearing deposit located within ring structure ~ 4 km diameter, in the form and size compares with small impact crater (Fig. 1). It is important impact event signature. Figure1: Cosmic image of Kumdy-Kol deposit area [http://map.google.ru/]. Diamond-bearing domain had been formed on the peak of UHP metamorphism provoked by comet impact under oblique angle on the Earth surface. As a result, steep falling system of tectonic dislocations, which breakage and fracture zones filling out of impact and host rock breccia with blastomylonitic and blastocataclastic textures have been created. Diamond-bearing domain has complicated lenticular-bloc structure (1300 x 40-200 m size) and lens out with deep about 300 m. -

Handbook of Iron Meteorites, Volume 2 (Canyon Diablo, Part 2)

Canyon Diablo 395 The primary structure is as before. However, the kamacite has been briefly reheated above 600° C and has recrystallized throughout the sample. The new grains are unequilibrated, serrated and have hardnesses of 145-210. The previous Neumann bands are still plainly visible , and so are the old subboundaries because the original precipitates delineate their locations. The schreibersite and cohenite crystals are still monocrystalline, and there are no reaction rims around them. The troilite is micromelted , usually to a somewhat larger extent than is present in I-III. Severe shear zones, 100-200 J1 wide , cross the entire specimens. They are wavy, fan out, coalesce again , and may displace taenite, plessite and minerals several millimeters. The present exterior surfaces of the slugs and wedge-shaped masses have no doubt been produced in a similar fashion by shear-rupture and have later become corroded. Figure 469. Canyon Diablo (Copenhagen no. 18463). Shock The taenite rims and lamellae are dirty-brownish, with annealed stage VI . Typical matte structure, with some co henite crystals to the right. Etched. Scale bar 2 mm. low hardnesses, 160-200, due to annealing. In crossed Nicols the taenite displays an unusual sheen from many small crystals, each 5-10 J1 across. This kind of material is believed to represent shock annealed fragments of the impacting main body. Since the fragments have not had a very long flight through the atmosphere, well developed fusion crusts and heat-affected rim zones are not expected to be present. The energy responsible for bulk reheating of the small masses to about 600° C is believed to have come from the conversion of kinetic to heat energy during the impact and fragmentation. -

Evidence from Polymict Ureilite Meteorites for a Disrupted and Re-Accreted Single Ureilite Parent Asteroid Gardened by Several Distinct Impactors

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 72 (2008) 4825–4844 www.elsevier.com/locate/gca Evidence from polymict ureilite meteorites for a disrupted and re-accreted single ureilite parent asteroid gardened by several distinct impactors Hilary Downes a,b,*, David W. Mittlefehldt c, Noriko T. Kita d, John W. Valley d a School of Earth Sciences, Birkbeck University of London, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HX, UK b Lunar and Planetary Institute, 3600 Bay Area Boulevard, Houston, TX 77058, USA c Mail Code KR, NASA/Johnson Space Center, Houston, TX 77058, USA d Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1215 W. Dayton St., Madison, WI 53706, USA Received 25 July 2007; accepted in revised form 24 June 2008; available online 17 July 2008 Abstract Ureilites are ultramafic achondrites that exhibit heterogeneity in mg# and oxygen isotope ratios between different meteor- ites. Polymict ureilites represent near-surface material of the ureilite parent asteroid(s). Electron microprobe analyses of >500 olivine and pyroxene clasts in several polymict ureilites reveal a statistically identical range of compositions to that shown by unbrecciated ureilites, suggesting derivation from a single parent asteroid. Many ureilitic clasts have identical compositions to the anomalously high Mn/Mg olivines and pyroxenes from the Hughes 009 unbrecciated ureilite (here termed the ‘‘Hughes cluster”). Some polymict samples also contain lithic clasts derived from oxidized impactors. The presence of several common distinctive lithologies within polymict ureilites is additional evidence that ureilites were derived from a single parent asteroid. In situ oxygen three isotope analyses were made on individual ureilite minerals and lithic clasts, using a secondary ion mass spectrometer (SIMS) with precision typically better than 0.2–0.4& (2SD) for d18O and d17O. -

POSTER SESSION 5:30 P.M

Monday, July 27, 1998 POSTER SESSION 5:30 p.m. Edmund Burke Theatre Concourse MARTIAN AND SNC METEORITES Head J. W. III Smith D. Zuber M. MOLA Science Team Mars: Assessing Evidence for an Ancient Northern Ocean with MOLA Data Varela M. E. Clocchiatti R. Kurat G. Massare D. Glass-bearing Inclusions in Chassigny Olivine: Heating Experiments Suggest Nonigneous Origin Boctor N. Z. Fei Y. Bertka C. M. Alexander C. M. O’D. Hauri E. Shock Metamorphic Features in Lithologies A, B, and C of Martian Meteorite Elephant Moraine 79001 Flynn G. J. Keller L. P. Jacobsen C. Wirick S. Carbon in Allan Hills 84001 Carbonate and Rims Terho M. Magnetic Properties and Paleointensity Studies of Two SNC Meteorites Britt D. T. Geological Results of the Mars Pathfinder Mission Wright I. P. Grady M. M. Pillinger C. T. Further Carbon-Isotopic Measurements of Carbonates in Allan Hills 84001 Burckle L. H. Delaney J. S. Microfossils in Chondritic Meteorites from Antarctica? Stay Tuned CHONDRULES Srinivasan G. Bischoff A. Magnesium-Aluminum Study of Hibonites Within a Chondrulelike Object from Sharps (H3) Mikouchi T. Fujita K. Miyamoto M. Preferred-oriented Olivines in a Porphyritic Olivine Chondrule from the Semarkona (LL3.0) Chondrite Tachibana S. Tsuchiyama A. Measurements of Evaporation Rates of Sulfur from Iron-Iron Sulfide Melt Maruyama S. Yurimoto H. Sueno S. Spinel-bearing Chondrules in the Allende Meteorite Semenenko V. P. Perron C. Girich A. L. Carbon-rich Fine-grained Clasts in the Krymka (LL3) Chondrite Bukovanská M. Nemec I. Šolc M. Study of Some Achondrites and Chondrites by Fourier Transform Infrared Microspectroscopy and Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy Semenenko V. -

Impact Shock Origin of Diamonds in Ureilite Meteorites

Impact shock origin of diamonds in ureilite meteorites Fabrizio Nestolaa,b,1, Cyrena A. Goodrichc,1, Marta Moranad, Anna Barbarod, Ryan S. Jakubeke, Oliver Christa, Frank E. Brenkerb, M. Chiara Domeneghettid, M. Chiara Dalconia, Matteo Alvarod, Anna M. Fiorettif, Konstantin D. Litasovg, Marc D. Friesh, Matteo Leonii,j, Nicola P. M. Casatik, Peter Jenniskensl, and Muawia H. Shaddadm aDepartment of Geosciences, University of Padova, I-35131 Padova, Italy; bGeoscience Institute, Goethe University Frankfurt, 60323 Frankfurt, Germany; cLunar and Planetary Institute, Universities Space Research Association, Houston, TX 77058; dDepartment of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Pavia, I-27100 Pavia, Italy; eAstromaterials Research and Exploration Science Division, Jacobs Johnson Space Center Engineering, Technology and Science, NASA, Houston, TX 77058; fInstitute of Geosciences and Earth Resources, National Research Council, I-35131 Padova, Italy; gVereshchagin Institute for High Pressure Physics RAS, Troitsk, 108840 Moscow, Russia; hNASA Astromaterials Acquisition and Curation Office, Johnson Space Center, NASA, Houston, TX 77058; iDepartment of Civil, Environmental and Mechanical Engineering, University of Trento, I-38123 Trento, Italy; jSaudi Aramco R&D Center, 31311 Dhahran, Saudi Arabia; kSwiss Light Source, Paul Scherrer Institut, 5232 Villigen, Switzerland; lCarl Sagan Center, SETI Institute, Mountain View, CA 94043; and mDepartment of Physics and Astronomy, University of Khartoum, 11111 Khartoum, Sudan Edited by Mark Thiemens, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, and approved August 12, 2020 (received for review October 31, 2019) The origin of diamonds in ureilite meteorites is a timely topic in to various degrees and in these samples the graphite areas, though planetary geology as recent studies have proposed their formation still having external blade-shaped morphologies, are internally at static pressures >20 GPa in a large planetary body, like diamonds polycrystalline (18). -

Lindsey Prewitt,Moissanite –

Feature Friday – Lindsey Prewitt I was looking for a job when someone told me Stuller was having a career fair. I went and met with a few people from marketing then I applied for a position as a Loyalty Program Manager. I landed an interview and clearly remember the interesting question asked on my way out: If I were the Public Relations person for Jeep and their vehicles’ gas tanks began exploding, what would I do to keep customers coming back? I was asked to send my response via email in the next few days. So I got online and researched everything from Jeep loyalty to gas tank explosions! I even called my uncle, a mechanic, to talk through the design aspects of automobiles and gain a better understanding of the “issue” at hand. I typed up my report and sent it to my interviewers. I suppose I left a lasting impression because they told me I’d be a great fit for a different position within the company. That’s when I met with Stanley Zale and the gemstone team. I started working here in May of 2015. Lindsey with a customer at JCK Las Vegas Here I am a year and a half down the road, and I still feel grateful for the wonderful opportunity. I am a Gemstone Product Manager. Many know me as the Moissanite Lady as well, but I’m in charge of all the brands:Charles and Colvard Moissanite, Chatham, and Swarovski, plus imitations and synthetics. I have a hand in everything associated with these gemstones, from marketing on the web and in print, facilitating customer interaction atBridge , tradeshows, Transform Tours, etc.