Handbook of Iron Meteorites, Volume 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meteorites and Impacts: Research, Cataloguing and Geoethics

Seminario_10_2013_d 10/6/13 17:12 Página 75 Meteorites and impacts: research, cataloguing and geoethics / Jesús Martínez-Frías Centro de Astrobiología, CSIC-INTA, asociado al NASA Astrobiology Institute, Ctra de Ajalvir, km. 4, 28850 Torrejón de Ardoz, Madrid, Spain Abstract Meteorites are basically fragments from asteroids, moons and planets which travel trough space and crash on earth surface or other planetary body. Meteorites and their impact events are two topics of research which are scientifically linked. Spain does not have a strong scientific tradition of the study of meteorites, unlike many other European countries. This contribution provides a synthetic overview about three crucial aspects related to this subject: research, cataloging and geoethics. At present, there are more than 20,000 meteorite falls, many of them collected after 1969. The Meteoritical Bulletin comprises 39 meteoritic records for Spain. The necessity of con- sidering appropriate protocols, scientific integrity issues and a code of good practice regarding the study of the abiotic world, also including meteorites, is emphasized. Resumen Los meteoritos son, básicamente, fragmentos procedentes de los asteroides, la Luna y Marte que chocan contra la superficie de la Tierra o de otro cuerpo planetario. Su estudio está ligado científicamente a la investigación de sus eventos de impacto. España no cuenta con una fuerte tradición científica sobre estos temas, al menos con el mismo nivel de desarrollo que otros paí- ses europeos. En esta contribución se realiza una revisión sintética de tres aspectos cruciales relacionados con los meteoritos: su investigación, catalogación y geoética. Hasta el momento se han reconocido más de 20.000 caídas meteoríticas, muchas de ellos desde 1969. -

Comet and Meteorite Traditions of Aboriginal Australians

Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures, 2014. Edited by Helaine Selin. Springer Netherlands, preprint. Comet and Meteorite Traditions of Aboriginal Australians Duane W. Hamacher Nura Gili Centre for Indigenous Programs, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, 2052, Australia Email: [email protected] Of the hundreds of distinct Aboriginal cultures of Australia, many have oral traditions rich in descriptions and explanations of comets, meteors, meteorites, airbursts, impact events, and impact craters. These views generally attribute these phenomena to spirits, death, and bad omens. There are also many traditions that describe the formation of meteorite craters as well as impact events that are not known to Western science. Comets Bright comets appear in the sky roughly once every five years. These celestial visitors were commonly seen as harbingers of death and disease by Aboriginal cultures of Australia. In an ordered and predictable cosmos, rare transient events were typically viewed negatively – a view shared by most cultures of the world (Hamacher & Norris, 2011). In some cases, the appearance of a comet would coincide with a battle, a disease outbreak, or a drought. The comet was then seen as the cause and attributed to the deeds of evil spirits. The Tanganekald people of South Australia (SA) believed comets were omens of sickness and death and were met with great fear. The Gunditjmara people of western Victoria (VIC) similarly believed the comet to be an omen that many people would die. In communities near Townsville, Queensland (QLD), comets represented the spirits of the dead returning home. -

A New Sulfide Mineral (Mncr2s4) from the Social Circle IVA Iron Meteorite

American Mineralogist, Volume 101, pages 1217–1221, 2016 Joegoldsteinite: A new sulfide mineral (MnCr2S4) from the Social Circle IVA iron meteorite Junko Isa1,*, Chi Ma2,*, and Alan E. Rubin1,3 1Department of Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, U.S.A. 2Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California 91125, U.S.A. 3Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, U.S.A. Abstract Joegoldsteinite, a new sulfide mineral of end-member formula MnCr2S4, was discovered in the 2+ Social Circle IVA iron meteorite. It is a thiospinel, the Mn analog of daubréelite (Fe Cr2S4), and a new member of the linnaeite group. Tiny grains of joegoldsteinite were also identified in the Indarch EH4 enstatite chondrite. The chemical composition of the Social Circle sample determined by electron microprobe is (wt%) S 44.3, Cr 36.2, Mn 15.8, Fe 4.5, Ni 0.09, Cu 0.08, total 101.0, giving rise to an empirical formula of (Mn0.82Fe0.23)Cr1.99S3.95. The crystal structure, determined by electron backscattered diffraction, is aFd 3m spinel-type structure with a = 10.11 Å, V = 1033.4 Å3, and Z = 8. Keywords: Joegoldsteinite, MnCr2S4, new sulfide mineral, thiospinel, Social Circle IVA iron meteorite, Indarch EH4 enstatite chondrite Introduction new mineral by the International Mineralogical Association (IMA 2015-049) in August 2015. It was named in honor of Thiospinels have a general formula of AB2X4 where A is a divalent metal, B is a trivalent metal, and X is a –2 anion, Joseph (Joe) I. -

Nanomagnetic Properties of the Meteorite Cloudy Zone

Nanomagnetic properties of the meteorite cloudy zone Joshua F. Einslea,b,1, Alexander S. Eggemanc, Ben H. Martineaub, Zineb Saghid, Sean M. Collinsb, Roberts Blukisa, Paul A. J. Bagote, Paul A. Midgleyb, and Richard J. Harrisona aDepartment of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, CB2 3EQ, United Kingdom; bDepartment of Materials Science and Metallurgy, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, CB3 0FS, United Kingdom; cSchool of Materials, University of Manchester, Manchester, M13 9PL, United Kingdom; dCommissariat a` l’Energie Atomique et aux Energies Alternatives, Laboratoire d’electronique´ des Technologies de l’Information, MINATEC Campus, Grenoble, F-38054, France; and eDepartment of Materials, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX1 3PH, United Kingdom Edited by Lisa Tauxe, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, and approved October 3, 2018 (received for review June 1, 2018) Meteorites contain a record of their thermal and magnetic history, field, it has been proposed that the cloudy zone preserves a written in the intergrowths of iron-rich and nickel-rich phases record of the field’s intensity and polarity (5, 6). The ability that formed during slow cooling. Of intense interest from a mag- to extract this paleomagnetic information only recently became netic perspective is the “cloudy zone,” a nanoscale intergrowth possible with the advent of high-resolution X-ray magnetic imag- containing tetrataenite—a naturally occurring hard ferromagnetic ing methods, which are capable of quantifying the magnetic state mineral that -

Orbit and Dynamic Origin of the Recently Recovered Annama’S H5 Chondrite

ORBIT AND DYNAMIC ORIGIN OF THE RECENTLY RECOVERED ANNAMA’S H5 CHONDRITE Josep M. Trigo-Rodríguez1 Esko Lyytinen2 Maria Gritsevich2,3,4,5,8 Manuel Moreno-Ibáñez1 William F. Bottke6 Iwan Williams7 Valery Lupovka8 Vasily Dmitriev8 Tomas Kohout 2, 9, 10 Victor Grokhovsky4 1 Institute of Space Science (CSIC-IEEC), Campus UAB, Facultat de Ciències, Torre C5-parell-2ª, 08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Finnish Fireball Network, Helsinki, Finland. 3 Dept. of Geodesy and Geodynamics, Finnish Geospatial Research Institute (FGI), National Land Survey of Finland, Geodeentinrinne 2, FI-02431 Masala, Finland 4 Dept. of Physical Methods and Devices for Quality Control, Institute of Physics and Technology, Ural Federal University, Mira street 19, 620002 Ekaterinburg, Russia. 5 Russian Academy of Sciences, Dorodnicyn Computing Centre, Dept. of Computational Physics, Valilova 40, 119333 Moscow, Russia. 6 Southwest Research Institute, 1050 Walnut St., Suite 300, Boulder, CO 80302, USA. 7Astronomy Unit, Queen Mary, University of London, Mile End Rd. London E1 4NS, UK. 8 Moscow State University of Geodesy and Cartography (MIIGAiK), Extraterrestrial Laboratory, Moscow, Russian Federation 9Department of Physics, University of Helsinki, P.O. Box 64, 00014 Helsinki University, Finland 10Institute of Geology, The Czech Academy of Sciences, Rozvojová 269, 16500 Prague 6, Czech Republic Abstract: We describe the fall of Annama meteorite occurred in the remote Kola Peninsula (Russia) close to Finnish border on April 19, 2014 (local time). The fireball was instrumentally observed by the Finnish Fireball Network. From these observations the strewnfield was computed and two first meteorites were found only a few hundred meters from the predicted landing site on May 29th and May 30th 2014, so that the meteorite (an H4-5 chondrite) experienced only minimal terrestrial alteration. -

A Catalogue of Large Meteorite Specimens from Campo Del Cielo Meteorite Shower, Chaco Province , Argentina

69th Annual Meteoritical Society Meeting (2006) 5001.pdf A CATALOGUE OF LARGE METEORITE SPECIMENS FROM CAMPO DEL CIELO METEORITE SHOWER, CHACO PROVINCE , ARGENTINA. M. C. L. Rocca , Mendoza 2779-16A, Ciudad de Buenos Aires, Argentina, (1428DKU), [email protected]. Introduction: The Campo del Cielo meteorite field in Chaco Province, Argentina, (S 27º 30’, W 61 º42’) consists, at least, of 20 meteorite craters with an age of about 4000 years. The area is composed of sandy-clay sediments of Quaternary- recent age. The impactor was an Iron-Nickel Apollo-type asteroid (Octahedrite meteorite type IA) and plenty of meteorite specimens survived the impact. Impactor’s diameter is estimated 5 to 20 me- ters. The impactor came from the SW and entered into the Earth’s atmosphere in a low angle of about 9º. As a consequence , the aster- oid broke in many pieces before creating the craters. The first mete- orite specimens were discovered during the time of the Spanish colonization. Craters and meteorite fragments are widespread in an oval area of 18.5 x 3 km (SW-NE), thus Campo del Cielo is one of the largest meteorite’s crater fields known in the world. Crater nº 3, called “Laguna Negra” is the largest (diameter: 115 meters). Inside crater nº 10, called “Gómez”, (diameter about 25 m.), a huge meteorite specimen called “El Chaco”, of 37,4 Tons, was found in 1980. Inside crater nº 9, called “La Perdida” (diameter : 25 x 35 m.) several meteorite pieces were discovered weighing in total about 5200 kg. The following is a catalogue of large meteorite specimens (more than 200 Kg.) from this area as 2005. -

8. Projectile ˜˜˜

8. Projectile ˜˜˜ Meteoritic remnants of the impacting asteroid that produced Barringer Crater littered the landscape when exploration began ~115 years ago. As described in Chapter 1, meteoritic irons are what initially captured Foote’s interest and spurred Barringer’s interest in a possibly rich natural source of native metal. After Foote’s description was published, samples were collected by F. W. Volz at a nearby trading post and sold widely. Gilbert (1896) estimated that 10 tons of meteoritic debris had already been recovered by the time of his visit. Similarly, Barringer (1905) estimated that 10 to 15 tons of it were circulating around the world by the time his exploration work began. Fortunately, he tried to document the geographic and mass distribution of that debris in a detailed map, which is reproduced in Fig. 8.1. The map indicates that meteoritic irons were recovered from distances approaching 10 km. Gilbert (1896) apparently recovered a sample nearly 13 km beyond the crater rim. A lot of the meteoritic material was oxidized. It is sometimes simply called oxidized iron, but large masses are also called shale balls. A concentrated deposit of small oxidized iron fragments was found northeast of the crater, although those types of fragments are distributed in all directions around the crater. The current estimate of the recovered meteoritic iron mass is 30 tons (Nininger, 1949; Grady, 2000), although this is a highly uncertain number. Specimens were transported in pre-historical times and have been found scattered throughout Arizona (see, for example, Wasson, 1968). Specimens have also been illicitly removed in recent times, without any documentation of the locations or masses recovered. -

Handbook of Iron Meteorites, Volume 2 (Canyon Diablo, Part 2)

Canyon Diablo 395 The primary structure is as before. However, the kamacite has been briefly reheated above 600° C and has recrystallized throughout the sample. The new grains are unequilibrated, serrated and have hardnesses of 145-210. The previous Neumann bands are still plainly visible , and so are the old subboundaries because the original precipitates delineate their locations. The schreibersite and cohenite crystals are still monocrystalline, and there are no reaction rims around them. The troilite is micromelted , usually to a somewhat larger extent than is present in I-III. Severe shear zones, 100-200 J1 wide , cross the entire specimens. They are wavy, fan out, coalesce again , and may displace taenite, plessite and minerals several millimeters. The present exterior surfaces of the slugs and wedge-shaped masses have no doubt been produced in a similar fashion by shear-rupture and have later become corroded. Figure 469. Canyon Diablo (Copenhagen no. 18463). Shock The taenite rims and lamellae are dirty-brownish, with annealed stage VI . Typical matte structure, with some co henite crystals to the right. Etched. Scale bar 2 mm. low hardnesses, 160-200, due to annealing. In crossed Nicols the taenite displays an unusual sheen from many small crystals, each 5-10 J1 across. This kind of material is believed to represent shock annealed fragments of the impacting main body. Since the fragments have not had a very long flight through the atmosphere, well developed fusion crusts and heat-affected rim zones are not expected to be present. The energy responsible for bulk reheating of the small masses to about 600° C is believed to have come from the conversion of kinetic to heat energy during the impact and fragmentation. -

The Hamburg Meteorite Fall: Fireball Trajectory, Orbit and Dynamics

The Hamburg Meteorite Fall: Fireball trajectory, orbit and dynamics P.G. Brown1,2*, D. Vida3, D.E. Moser4, M. Granvik5,6, W.J. Koshak7, D. Chu8, J. Steckloff9,10, A. Licata11, S. Hariri12, J. Mason13, M. Mazur3, W. Cooke14, and Z. Krzeminski1 *Corresponding author email: [email protected] ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6130-7039 1Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, N6A 3K7, Canada 2Centre for Planetary Science and Exploration, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, N6A 5B7, Canada 3Department of Earth Sciences, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, N6A 3K7, Canada ( 4Jacobs Space Exploration Group, EV44/Meteoroid Environment Office, NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, AL 35812 USA 5Department of Physics, P.O. Box 64, 00014 University of Helsinki, Finland 6 Division of Space Technology, Luleå University of Technology, Kiruna, Box 848, S-98128, Sweden 7NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, ST11, Robert Cramer Research Hall, 320 Sparkman Drive, Huntsville, AL 35805, USA 8Chesapeake Aerospace LLC, Grasonville, MD 21638, USA 9Planetary Science Institute, Tucson, AZ, USA 10Department of Aerospace Engineering and Engineering Mechanics, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA 11Farmington Community Stargazers, Farmington Hills, MI, USA 12Department of Physics and Astronomy, Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti, MI, USA 13Orchard Ridge Campus, Oakland Community College, Farmington Hills, MI, USA 14NASA Meteoroid Environment Office, Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Alabama 35812, USA Accepted to Meteoritics and Planetary Science, June 19, 2019 85 pages, 4 tables, 15 figures, 1 appendix. Original submission September, 2018. 1 Abstract The Hamburg (H4) meteorite fell on January 17, 2018 at 01:08 UT approximately 10km North of Ann Arbor, Michigan. -

Lost Lake by Robert Verish

Meteorite-Times Magazine Contents by Editor Like Sign Up to see what your friends like. Featured Monthly Articles Accretion Desk by Martin Horejsi Jim’s Fragments by Jim Tobin Meteorite Market Trends by Michael Blood Bob’s Findings by Robert Verish IMCA Insights by The IMCA Team Micro Visions by John Kashuba Galactic Lore by Mike Gilmer Meteorite Calendar by Anne Black Meteorite of the Month by Michael Johnson Tektite of the Month by Editor Terms Of Use Materials contained in and linked to from this website do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of The Meteorite Exchange, Inc., nor those of any person connected therewith. In no event shall The Meteorite Exchange, Inc. be responsible for, nor liable for, exposure to any such material in any form by any person or persons, whether written, graphic, audio or otherwise, presented on this or by any other website, web page or other cyber location linked to from this website. The Meteorite Exchange, Inc. does not endorse, edit nor hold any copyright interest in any material found on any website, web page or other cyber location linked to from this website. The Meteorite Exchange, Inc. shall not be held liable for any misinformation by any author, dealer and or seller. In no event will The Meteorite Exchange, Inc. be liable for any damages, including any loss of profits, lost savings, or any other commercial damage, including but not limited to special, consequential, or other damages arising out of this service. © Copyright 2002–2010 The Meteorite Exchange, Inc. All rights reserved. No reproduction of copyrighted material is allowed by any means without prior written permission of the copyright owner. -

September 17, 2010 -- Oregon's Sixth Meteorite, Named Fitzwater Pass

NEWS RELEASE EMBARGOED UNTIL 1 PM P.S.T., SEPTEMBER 27, 2010 By: Alex Ruzicka, Melinda Hutson, Dick Pugh Source: Cascadia Meteorite Laboratory, Department of Geology, Portland State University, 503- 725-3372, email [email protected] Oregon’s sixth meteorite, named Fitzwater Pass, is discovered to be a rare type of iron. (Portland, Ore.) – September 27, 2010 After spending over 30 years in a Folgers coffee can, a thumb-sized chunk of metal has been identified by researchers as a rare type of iron meteorite. Named Fitzwater Pass, this meteorite adds to five other known meteorites from Oregon. Previous meteorites include Sam’s Valley (found 1894), Willamette (found 1902), Klamath Falls (found 1952), Salem (fell 1981), and Morrow County (recognized 2010). Meteorites are named for the nearest geographical feature. The meteorite was found in the early summer of 1976 by Mr. Paul Albertson of Lakeview, Oregon, while hunting for agate and jasper at Fitzwater Pass in south central Oregon with his high school teacher James Bleakney. Mr. Albertson took the 65 gram (2.3 ounce) teardrop-shaped piece of metal to a local rock shop, where a small amount was ground off. He was told by someone at the rock shop that it was probably a piece of nickel ore. Mr. Albertson placed the rock in a Folgers coffee can, where it remained until 2006. The meteorite made it out of the can and into the hands of Dick Pugh, a member of the Cascadia Meteorite Laboratory (CML) at Portland State University, Portland, Oregon, who recognized it as a probable meteorite. -

Tree-Ring Dating of Meteorite Fall in Sikhote-Alin, Eastern Siberia – Russia

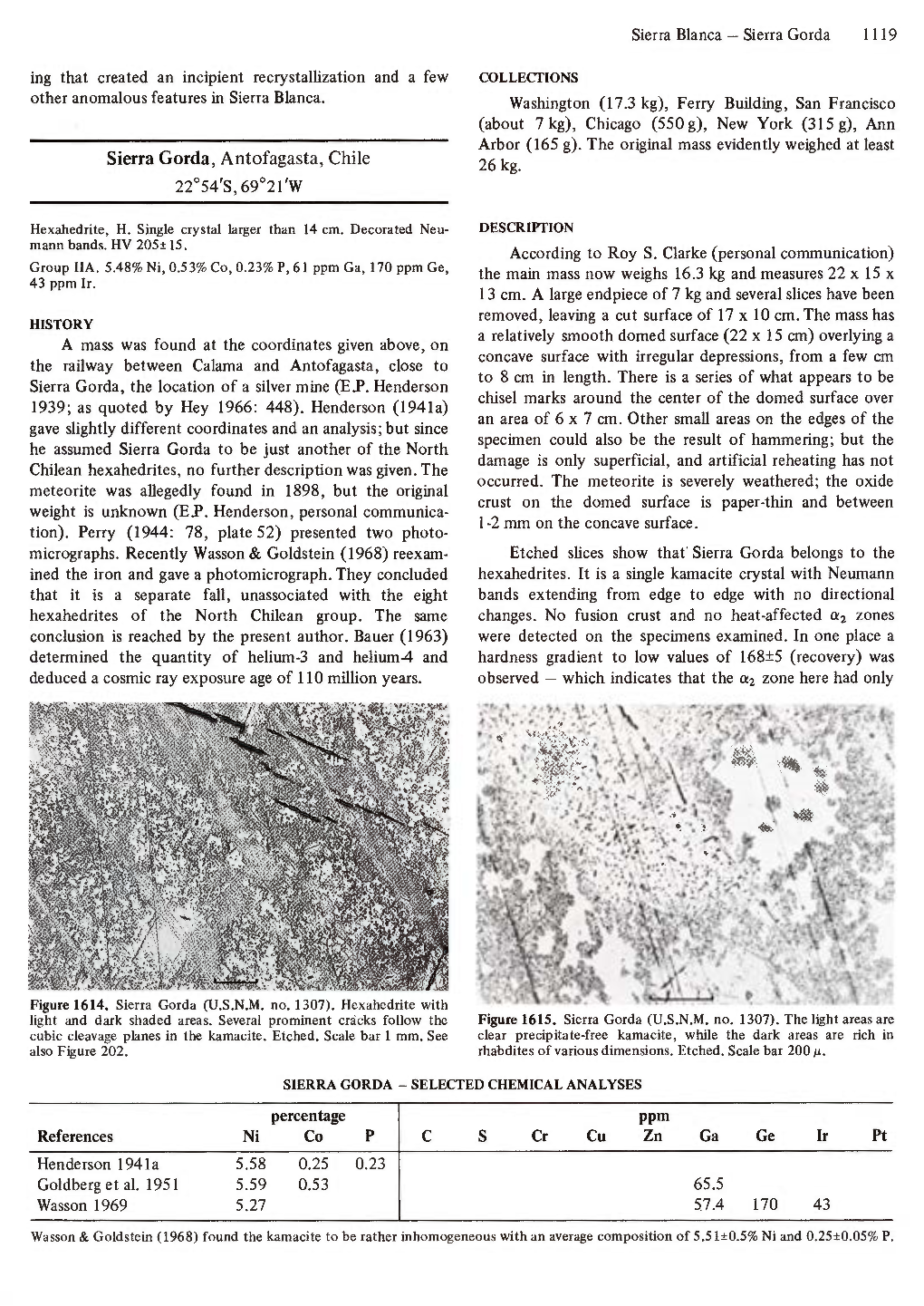

International Journal of Astrobiology, Page 1 of 6 1 doi:10.1017/S1473550411000309 © Cambridge University Press 2011 Tree-ring dating of meteorite fall in Sikhote-Alin, Eastern Siberia – Russia R. Fantucci1, Mario Di Martino2 and Romano Serra3 1Geologi Associati Fantucci e Stocchi, 01027 Montefiascone (VT), Italy e-mail: [email protected] 2INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Torino, 10025 Pino Torinese, Italy 3Dipartimento di Fisica, Università di Bologna, via Irnerio 46, 40126 Bologna, Italy Abstract: This research deals with the fall of the Sikhote-Alin iron meteorite on the morning of 12 February 1947, at about 00:38 h Utrecht, in a remote area in the territory of Primorsky Krai in Eastern Siberia (46°09′ 36″N, 134°39′22″E). The area engulfed by the meteoritic fall was around 48 km2, with an elliptic form and thousands of craters. Around the large craters the trees were torn out by the roots and laid radially to the craters at a distance of 10–20 m; the more distant trees had broken tops. This research investigated through dendrocronology n.6 Scots pine trees (Pinus Sibirica) close to one of the main impact craters. The analysis of growth anomalies has shown a sudden decrease since 1947 for 4–8 years after the meteoritic impact. Tree growth stress, detected in 1947, was analysed in detail through wood microsection that confirmed the winter season (rest vegetative period) of the event. The growth stress is mainly due to the lost crown (needle lost) and it did not seem to be caused due to direct damages on trunk and branches (missing of resin ducts).