American Journal of Science, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

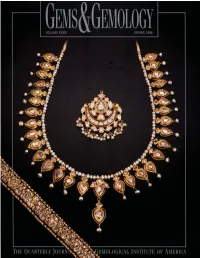

Spring 1998 Gems & Gemology

VOLUME 34 NO. 1 SPRING 1998 TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITORIAL 1 The Dr. Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award FEATURE ARTICLE 4 The Rise to pProminence of the Modern Diamond Cutting Industry in India Menahem Sevdermish, Alan R. Miciak, and Alfred A. Levinson pg. 7 NOTES AND NEW TECHNIQUES 24 Leigha: The Creation of a Three-Dimensional Intarsia Sculpture Arthur Lee Anderson 34 Russian Synthetic Pink Quartz Vladimir S. Balitsky, Irina B. Makhina, Vadim I. Prygov, Anatolii A. Mar’in, Alexandr G. Emel’chenko, Emmanuel Fritsch, Shane F. McClure, Lu Taijing, Dino DeGhionno, John I. Koivula, and James E. Shigley REGULAR FEATURES pg. 30 44 Gem Trade Lab Notes 50 Gem News 64 Gems & Gemology Challenge 66 Book Reviews 68 Gemological Abstracts ABOUT THE COVER: Over the past 30 years, India has emerged as the dominant sup- plier of small cut diamonds for the world market. Today, nearly 70% by weight of the diamonds polished worldwide come from India. The feature article in this issue discuss- es India’s near-monopoly of the cut diamond industry, and reviews India’s impact on the worldwide diamond trade. The availability of an enormous amount of small, low-cost pg. 42 Indian diamonds has recently spawned a growing jewelry manufacturing sector in India. However, the Indian diamond jewelery–making tradition has been around much longer, pg. 46 as shown by the 19th century necklace (39.0 cm long), pendant (4.5 cm high), and bracelet (17.5 cm long) on the cover. The necklace contains 31 table-cut diamond panels, with enamels and freshwater pearls. -

Mineral Classifications-No Links

CLASSIFYING MINERALS Minerals are divided into nine (9) broad classifications. They are typically classified based on the negatively charged (anionic) portion of their chemical composition. For example, copper oxide (CuO) consists of copper (Cu ++ ) and oxygen (O -- ) ions, and the negatively charged oxygen ion puts it in the “Oxide” classification (which also includes iron oxide, titanium dioxide, etc). The classifications are: Silicate class The largest group of minerals by far, the silicates are mostly composed of silicon and oxygen, combined with ions like aluminum, magnesium, iron, and calcium. Some important rock-forming silicates include the feldspars, quartz, olivines, pyroxenes, garnets, and micas. Carbonate class 2− The carbonate minerals contain the anion (CO 3) . They are deposited in marine settings from accumulated shells of marine life and also in evaporitic areas like the Great Salt Lake and karst regions where they form caves, stalactites and stalagmites. Typical carbonates include calcite and aragonite (both calcium carbonate), dolomite (magnesium/calcium carbonate) and siderite (iron carbonate). The carbonate class also includes the nitrate and borate minerals. Sulfate class 2− Sulfate minerals all contain the sulfate anion, SO 4 . Sulfates commonly form in evaporitic settings where highly saline waters slowly evaporate, in hydrothermal vein systems as gangue minerals and as secondary oxidation products of original sulfide minerals. Common sulfates include anhydrite (calcium sulfate), celestine (strontium sulfate), barite (barium sulfate), and gypsum (hydrated calcium sulfate). The sulfate class also includes the chromate, molybdate, selenate, sulfite, tellurate, and tungstate minerals. Halide class The halide minerals form the natural salts and include fluorite (calcium fluoride), halite (sodium chloride) and sylvite (potassium chloride). -

Accretion of Water in Carbonaceous Chondrites: Current Evidence and Implications for the Delivery of Water to Early Earth

ACCRETION OF WATER IN CARBONACEOUS CHONDRITES: CURRENT EVIDENCE AND IMPLICATIONS FOR THE DELIVERY OF WATER TO EARLY EARTH Josep M. Trigo-Rodríguez1,2, Albert Rimola3, Safoura Tanbakouei1,3, Victoria Cabedo Soto1,3, and Martin Lee4 1 Institute of Space Sciences (CSIC), Campus UAB, Facultat de Ciències, Torre C5-parell-2ª, 08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Institut d’Estudis Espacials de Catalunya (IEEC), Edif.. Nexus, c/Gran Capità, 2-4, 08034 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain 3 Departament de Química, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 08193 Bellaterra, Catalonia, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] 4 School of Geographical and Earth Sciences, University of Glasgow, Gregory Building, Lilybank Gardens, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK. Manuscript Pages: 37 Tables: 2 Figures: 10 Keywords: comet; asteroid; meteoroid; meteorite; minor bodies; primitive; tensile strength Accepted in Space Science Reviews (SPAC-D-18-00036R3, Vol. Ices in the Solar System) DOI: 10.1007/s11214-019-0583-0 Abstract: Protoplanetary disks are dust-rich structures around young stars. The crystalline and amorphous materials contained within these disks are variably thermally processed and accreted to make bodies of a wide range of sizes and compositions, depending on the heliocentric distance of formation. The chondritic meteorites are fragments of relatively small and undifferentiated bodies, and the minerals that they contain carry chemical signatures providing information about the early environment available for planetesimal formation. A current hot topic of debate is the delivery of volatiles to terrestrial planets, understanding that they were built from planetesimals formed under far more reducing conditions than the primordial carbonaceous chondritic bodies. -

A New Occurrence of Terrestrial Native Iron in the Earth's Surface

geosciences Article A New Occurrence of Terrestrial Native Iron in the Earth’s Surface: The Ilia Thermogenic Travertine Case, Northwestern Euboea, Greece Christos Kanellopoulos 1,2,* ID , Eugenia Valsami-Jones 3,4, Panagiotis Voudouris 1, Christina Stouraiti 1 ID , Robert Moritz 2, Constantinos Mavrogonatos 1 ID and Panagiotis Mitropoulos 1,† 1 Department of Geology and Geoenvironment, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Panepistimioupolis Zografou, 15784 Athens, Greece; [email protected] (P.V.); [email protected] (C.S.); [email protected] (C.M.); [email protected] (P.M.) 2 Section of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Geneva, Rue des Maraichers 13, 1205 Geneva, Switzerland; [email protected] 3 School of Geography, Earth & Environmental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK; [email protected] 4 Department of Earth Sciences, Natural History Museum London, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] † Professor Panagiotis Mitropoulos has passed away in 2017. Received: 6 April 2018; Accepted: 23 July 2018; Published: 31 July 2018 Abstract: Native iron has been identified in an active thermogenic travertine deposit, located at Ilia area (Euboea Island, Greece). The deposit is forming around a hot spring, which is part of a large active metallogenetic hydrothermal system depositing ore-bearing travertines. The native iron occurs in two shapes: nodules with diameter 0.4 and 0.45 cm, and angular grains with length up to tens of µm. The travertine laminae around the spherical/ovoid nodules grow smoothly, and the angular grains are trapped inside the pores of the travertine. -

U-Pb Age, Re-Os Isotopes, and Hse Geochemistry of Northwest Africa 6704

44th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2013) 1841.pdf U-PB AGE, RE-OS ISOTOPES, AND HSE GEOCHEMISTRY OF NORTHWEST AFRICA 6704. T. Iizuka1, Y. Amelin2, I. S. Puchtel3, R. J. Walker3, A. J. Irving4, A. Yamaguchi5, Y. Takagi6, T. Noguchi6 and M. Kimura5. 1Department of Earth and Planetary Science, University of Tokyo, Hongo 7-3-1, Bunkyo, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan ([email protected]), 2Research School of Earth Sciences, Australian National University, Canberra ACT, Australia, 3Department of Geology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA, 4Department of Earth and Space Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA, 5National Institute of Polar Research, Tachikawa, Tokyo 190-8518, Japan, 6College of Science, Ibaraki University, Bunkyo 2-1-1, Mito, Ibaraki 310-8512, Japan. Introduction: Northwest Africa (NWA) 6704 is a of Maryland using standard high temperature acid diges- very unusual ungrouped fresh achondrite. It consists of tion, chemical purification and mass spectrometry tech- abundant coarse-grained (up to 1.5 mm) low-Ca py- niques [3]. The quantities of each of the HSE was at roxene, less abundant olivine, chromite, merrillite and least 1000 times greater than the blanks measured at the interstitial sodic plagioclase. Minor minerals are same time. Thus, blanks had no impact on the measure- awaruite, heazlewoodite, and pentlandite. Raman spec- ments. Accuracy and precision of Ir, Ru, Pt and Pd con- troscopy shows that a majority of the low-Ca pyroxene centrations are estimated to be <2%, of Re <0.4%, and is orthopyroxene. Bulk major element abundances are of Os <0.1%. -

Evolution of the Iron–Silicate and Carbon Material of Carbonaceous Chondrites A

ISSN 01458752, Moscow University Geology Bulletin, 2013, Vol. 68, No. 5, pp. 265–281. © Allerton Press, Inc., 2013. Original Russian Text © A.A. Marakushev, L.I. Glazovskaya, S.A. Marakushev, 2013, published in Vestnik Moskovskogo Universiteta. Geologiya, 2013, No. 5, pp. 3–17. Evolution of the Iron–Silicate and Carbon Material of Carbonaceous Chondrites A. A. Marakusheva, L. I. Glazovskayab, and S. A. Marakushevc aInstitute of Experimental Mineralogy, Russian Academy of Sciences, Chernogolovka, Moscow oblast, 142432 Russia email: [email protected] bFaculty of Geology, Moscow State University, Moscow, 119234 Russia email: [email protected] cInstitute of Problems of Chemical Physics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Chernogolovka, Moscow oblast, 142432 Russia email: [email protected] Received February 18, 2013 Abstract—The observed consistence of the composition of chondrules and the matrix in chondrites is explained by their origin as a result of chondrule–matrix splitting of the material of primitive (not layered) planets. According to the composition of chondrites, two main stages in the evolution of chondritic planets (silicate–metallic and olivine) are distinguished. Chondritic planets of the silicate–metallic stage were ana logs of chondritic planets, whose layering resulted in the formation of the terrestrial planets. The iron–silicate evolution of chondritic matter is correlated with the evolution of carbon material in the following sequence: diamond ± moissanite → hydrocarbons → primitive organic compounds. Keywords: meteorite matter, carbonaceous chondrites, hydrocarbons DOI: 10.3103/S0145875213050074 INTRODUCTION 2003) in star–planet systems that are similar to the solar system, in which nearstar giant planets were still The occurrence of diamond in a stable paragenesis preserved and are distinguished under the name rapid with moissanite (SiC) in an ironrich matrix is a char Jupiters. -

Lunar and Planetary Science XXX 1753.Pdf

Lunar and Planetary Science XXX 1753.pdf INTERSTELLAR DIAMOND. II. GROWTH AND IDENTIFICATION. Andrew W. Phelps, University of Dayton Research Institute, Materials Engineering Division (300 College Park, Dayton OH, 45469-0130, [email protected]). likely form clumps of carbon that look much like the Introduction: The first abstract in this series starting material – hydrogen rich sp3 bound clusters. suggested that many types of diamond are found in many types of meteoritic material and that the The compounds that fit the requirements above variation in polytype abundance appears to reflect the include the cycloalkanes such as adamantane [21-30] nature of the host. How the diamonds got there and (C10H16) and bicyclooctane (C6H8) (BCO) . what they mean will now be examined. Opinions These compounds ‘look’ like small cubic diamonds regarding the formation mechanism(s) of meteoritic and lonsdaleite respectively. If these particular and interstellar diamond grains have changed over compounds are suggested as models for diamond the years as new methods of making synthetic nuclei then a number of structural and diamond were developed[1,2]. Meteoritic diamonds thermodynamic predictions can be made about the were once believed to be the result of high pressure - types of diamond that can form and its relative temperature processes in the interior of planetary abundance with regard to the physics and chemistry bodies[3,4]. Impact formation of diamond became of its growth environment. A few examples of this popular after the development of shock wave are: Adamantane is a lower energy form and would diamond synthesis[5] because shock synthesis was tend to form in an environment of sufficient thermal able to form lonsdaleite and meteorites were full of energy to allow the molecule to organize into this lonsdaleite. -

Meteorites from the Lut Desert (Iran)

Meteorites from the Lut Desert (Iran) Hamed Pourkhorsandi, Jérôme Gattacceca, Pierre Rochette, Massimo d’Orazio, Hojat Kamali, Roberto Avillez, Sonia Letichevsky, Morteza Djamali, Hassan Mirnejad, Vinciane Debaille, et al. To cite this version: Hamed Pourkhorsandi, Jérôme Gattacceca, Pierre Rochette, Massimo d’Orazio, Hojat Kamali, et al.. Meteorites from the Lut Desert (Iran). Meteoritics and Planetary Science, Wiley, 2019, 54 (8), pp.1737-1763. 10.1111/maps.13311. hal-02144596 HAL Id: hal-02144596 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02144596 Submitted on 31 May 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - ShareAlike| 4.0 International License doi: 10.1111/maps.13311 Meteorites from the Lut Desert (Iran) Hamed POURKHORSANDI 1,2*,Jerome^ GATTACCECA 1, Pierre ROCHETTE 1, Massimo D’ORAZIO3, Hojat KAMALI4, Roberto de AVILLEZ5, Sonia LETICHEVSKY5, Morteza DJAMALI6, Hassan MIRNEJAD7, Vinciane DEBAILLE2, and A. J. Timothy JULL8 1Aix Marseille Universite, CNRS, IRD, Coll France, INRA, CEREGE, Aix-en-Provence, France 2Laboratoire G-Time, Universite Libre de Bruxelles, CP 160/02, 50, Av. F.D. Roosevelt, 1050 Brussels, Belgium 3Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Universita di Pisa, Via S. -

Impact−Cosmic−Metasomatic Origin of Microdiamonds from Kumdy−Kol Deposit, Kokchetav Massiv, N

11th International Kimberlite Conference Extended Abstract No. 11IKC-4506, 2017 Impact−Cosmic−Metasomatic Origin of Microdiamonds from Kumdy−Kol Deposit, Kokchetav Massiv, N. Kazakhstan L. I. Tretiakova1 and A. M. Lyukhin2 1St. Petersburg Branch Russian Mineralogical Society. RUSSIA, [email protected] 2Institute of remote ore prognosis, Moscow, RUSSIA, [email protected] Introduction Any collision extraterrestrial body and the Earth had left behind the “signature” on the Earth’s surface. We are examining a lot of signatures of an event caused Kumdy-Kol diamond-bearing deposit formation, best- known as “metamorphic” diamond locality among numerous UHP terrains around the world. We are offering new impact-cosmic-metasomatic genesis of this deposit and diamond origin provoked by impact event followed prograde and retrograde metamorphism with metasomatic alterations of collision area rocks that have been caused of diamond nucleation, growth and preserve. Brief geology of Kumdy-Kol diamond-bearing deposit Kumdy-Kol diamond-bearing deposit located within ring structure ~ 4 km diameter, in the form and size compares with small impact crater (Fig. 1). It is important impact event signature. Figure1: Cosmic image of Kumdy-Kol deposit area [http://map.google.ru/]. Diamond-bearing domain had been formed on the peak of UHP metamorphism provoked by comet impact under oblique angle on the Earth surface. As a result, steep falling system of tectonic dislocations, which breakage and fracture zones filling out of impact and host rock breccia with blastomylonitic and blastocataclastic textures have been created. Diamond-bearing domain has complicated lenticular-bloc structure (1300 x 40-200 m size) and lens out with deep about 300 m. -

NEW MINERAL NAMES Mrcnnnr Fr-Brscnpn

THE AMERICAN MINERAI,OGIST, VOL. 55, JANUARY-FEBRUARY, 1970 NEW MINERAL NAMES Mrcnnnr Fr-Brscnpn Barringerite P. R. Busrcr (1969) Phosphide from meteorites.' Barringerite, a new iron-nickel mineral. Sci,ence165, 169-17 1,. The average of microprobe analyses was Fe 44.3*0.9, Ni 33.9+0.7, Co 0.25+0.03, P 21.8+0.4, stm 10O.25/6,corresponding to (Irer.roNio.srCoo.n)P,or (Fe, Ni)rP. X-ray study shows it to be hexagonal,space group P62 m, a 5.87 -t0.07, c 3.M+0.04 ft. The strongest X-ray lines (including many overlapping troilite or schreibersite; those starred do not overlap) are 2.98 (110),2.85* (101),2.53(200),2.23(lll),2.03*(201), 1.88* (r20), r.72(t00), 1.68(300, t2r), L.48(220), t.4t(3t0, 22r), r.29*(31r), 1.28(122), t.27 (400), 1.205(302),1.197(4oD.The structure is similar to those of synthetic FerP and NirP. p (calc) 6.92. Color white, very similar to that of kamacite, bluish compared to schreibersite. Harder than either kamacite or schreibersite. Reflectivity in air and oil slightly higher than that of schreibersite, lower than that of kamacite. Noticeably anisotropic (white to blue). Bireflectance not observed. The mineral occurs as bands 10-15 pm wide and several hundred microns long; they consist of individual grains less than 1 pm in diameter. They occur in the Ollague pallasite along the contacts between schreibersite and troilite. The name is for D. -

Recent Observations of the Soils on the Moon

Lunar Soil for a Myriad of Purposes and Products: Science, Engineering, and Applications LawrenceLawrence A.A. TaylorTaylor PPlanetary Geosciences Institute University of Tennessee Objectives NEW LUNAR SAMPLES UNIQUE PROPERTIES OF LUNAR SOIL NEW LUNAR MINERALS UNIQUE ABILITIES OF MICROWAVE RADIATION MICROWAVE PROCESSING OF LUNAR SOIL PRODUCTS FOR “THE BUSH LUNAR BASE” Newly Recovered Planetary Materials Meteorites from Antarctica Japan and USA Meteorites from Hot Deserts French Entrepreneurs in the Sahara Russian Entrepreneurs in Oman Meteorites as samples of : as well as Mars & Asteroidal Matter SEARCHING FOR METEORITES IN THE OMAN DESERT When viewed with binoculars, the Black Spot in the sand is: a) a ‘coke can’ [alcohol is verboten!]; b) evidence that a camel has stopped there recently; or c) a dark-colored rock [fusion crust on a meteorite]. Meteorite? LunarLunar MeteoritesMeteorites fromfrom OmanOman Dhofar 287 Dhofar 025 (Impact-Melt Breccia) (Basalt + Breccia) Regolith Breccia Dhofar 301 Dhofar 302 Dhofar 303 New Lunar Rocks and Minerals: Farside Samples of the Moon South Pole / Amundsen Site Volcanic Glass Impact-Glass Lunar Mare Soil Bead Bead Agglutinate Rock Chips Impact Glass 1 mm Plagioclase Our Unhappy Moon MicrometeoriteMicrometeorite ImpactsImpacts onon LunarLunar GlassGlass BeadBead 5 µm Impact Craters LunarLunar SoilSoil FormationFormation Comminution, Agglutination, & Vapor Deposition TheThe onlyonly WeatheringWeathering andand EErosionalrosional agentagent onon thethe MoonMoon isis MeteoriteMeteorite andand MicrometeoriteMicrometeorite -

Handbook of Iron Meteorites, Volume 2 (Canyon Diablo, Part 2)

Canyon Diablo 395 The primary structure is as before. However, the kamacite has been briefly reheated above 600° C and has recrystallized throughout the sample. The new grains are unequilibrated, serrated and have hardnesses of 145-210. The previous Neumann bands are still plainly visible , and so are the old subboundaries because the original precipitates delineate their locations. The schreibersite and cohenite crystals are still monocrystalline, and there are no reaction rims around them. The troilite is micromelted , usually to a somewhat larger extent than is present in I-III. Severe shear zones, 100-200 J1 wide , cross the entire specimens. They are wavy, fan out, coalesce again , and may displace taenite, plessite and minerals several millimeters. The present exterior surfaces of the slugs and wedge-shaped masses have no doubt been produced in a similar fashion by shear-rupture and have later become corroded. Figure 469. Canyon Diablo (Copenhagen no. 18463). Shock The taenite rims and lamellae are dirty-brownish, with annealed stage VI . Typical matte structure, with some co henite crystals to the right. Etched. Scale bar 2 mm. low hardnesses, 160-200, due to annealing. In crossed Nicols the taenite displays an unusual sheen from many small crystals, each 5-10 J1 across. This kind of material is believed to represent shock annealed fragments of the impacting main body. Since the fragments have not had a very long flight through the atmosphere, well developed fusion crusts and heat-affected rim zones are not expected to be present. The energy responsible for bulk reheating of the small masses to about 600° C is believed to have come from the conversion of kinetic to heat energy during the impact and fragmentation.