Reassessing the Capacities of Entertainment Structures in the Roman Empire J.W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Not for Publication United States Court of Appeals

NOT FOR PUBLICATION FILED AUG 28 2020 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS MOLLY C. DWYER, CLERK FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT U.S. COURT OF APPEALS EHM PRODUCTIONS, INC., DBA TMZ, a No. 19-55288 California corporation; WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT INC., a Delaware D.C. No. corporation, 2:16-cv-02001-SJO-GJS Plaintiffs-Appellees, MEMORANDUM* v. STARLINE TOURS OF HOLLYWOOD, INC., a California corporation, Defendant-Appellant. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California S. James Otero, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted August 10, 2020 Pasadena, California Before: WARDLAW and CLIFTON, Circuit Judges, and HILLMAN,** District Judge. Starline Tours of Hollywood, Inc. (Starline) appeals the district court’s * This disposition is not appropriate for publication and is not precedent except as provided by Ninth Circuit Rule 36-3. ** The Honorable Timothy Hillman, United States District Judge for the District of Massachusetts, sitting by designation. orders dismissing its First Amended Counterclaim (FACC) and denying its motion for leave to amend. We dismiss this appeal for lack of appellate jurisdiction. 1. Under 28 U.S.C. § 1291, the courts of appeals have jurisdiction over “final decisions of the district court.” Nat’l Distrib. Agency v. Nationwide Mut. Ins. Co., 117 F.3d 432, 433 (9th Cir. 1997). Generally, “a voluntary dismissal without prejudice is ordinarily not a final judgment from which the plaintiff may appeal.” Galaza v. Wolf, 954 F.3d 1267, 1270 (9th Cir. 2020) (cleaned up). A limited exception to this rule—which Starline seeks to invoke—permits an appeal “when a party that has suffered an adverse partial judgment subsequently dismisses its remaining claims without prejudice with the approval of the district court, and the record reveals no evidence of intent to manipulate our appellate jurisdiction.” James v. -

VESPASIAN. AD 68, Though Not a Particularly Constructive Year For

138 VESPASIAN. AD 68, though not a particularly constructive year for Nero, was to prove fertile ground for senators lion the make". Not that they were to have the time to build anything much other than to carve out a niche for themselves in the annals of history. It was not until the dust finally settled, leaving Vespasian as the last contender standing, that any major building projects were to be initiated under Imperial auspices. However, that does not mean that there is nothing in this period that is of interest to this study. Though Galba, Otho and Vitellius may have had little opportunity to indulge in any significant building activity, and probably given the length and nature of their reigns even less opportunity to consider the possibility of building for their future glory, they did however at the very least use the existing imperial buildings to their own ends, in their own ways continuing what were by now the deeply rooted traditions of the principate. Galba installed himself in what Suetonius terms the palatium (Suet. Galba. 18), which may not necessarily have been the Golden House of Nero, but was part at least of the by now agglomerated sprawl of Imperial residences in Rome that stretched from the summit of the Palatine hill across the valley where now stands the Colosseum to the slopes of the Oppian, and included the Golden House. Vitellius too is said to have used the palatium as his base in Rome (Suet. Vito 16), 139 and is shown by Suetonius to have actively allied himself with Nero's obviously still popular memory (Suet. -

Las Inscripciones De Cales (Calvi, Italia) Que El Marqués De Salamanca Dejó En Nápoles Y Algunas Notas Sobre Esculturas De Es

245 Las inscripciones de Cales (Calvi, Italia) que el marqués de Salamanca dejó en Nápoles y algunas notas sobre esculturas de esa procedencia en su colección arqueológica The inscriptions of Cales (Calvi, Italy) that the marquis of Salamanca left in Naples and some notes on sculptures of that origin in his archaeological collection José Beltrán Fortes ([email protected]) Universidad de Sevilla Resumen: La colección arqueológica del marqués de Salamanca fue conformada en el tercer cuarto del siglo XIX y comprada por el Museo Arqueológico Nacional (MAN), de Madrid, en 1874. Casi la totalidad de los materiales son de procedencia de la península Itálica, como de Paestum y Cales, donde Salamanca tuvo concesiones oficiales para llevar a cabo excavaciones. De Cales (Calvi) procedían cinco inscripciones que donó al Museo Arqueológico Nacional de Nápoles, así como otras esculturas que se conservan hoy en día en el Museo Arqueológico Nacional de Madrid. Palabras clave: Arqueología. Epigrafía. Escultura. Museos. Cales. Abstract: The archaeological collection of the marquis of Salamanca was made up in the third quarter of the nineteenth century and acquired by the MAN of Madrid in 1874. Almost all of the pieces are from the Italian peninsula, like Paestum and Cales, where Salamanca had some official permission in order to carry out excavations. Five inscriptions came from Cales (Calvi), which he donated to the National Archaeological Museum of Naples, as well as other sculptures, that today are preserved in the MAN of Madrid. Keywords: Archaeology. Epigraphy. Sculpture. Museums. Cales. 1. Introducción José de Salamanca y Mayol (Málaga, 1811-Madrid, 1883) conformó la más importante colección arqueológica española de carácter particular del siglo XIX, que, afortunadamente en 1874, mediante Orden de 10 de mayo, fue adquirida por el Estado para engrosar los fondos del Boletín del Museo Arqueológico Nacional 36/2017 | Págs. -

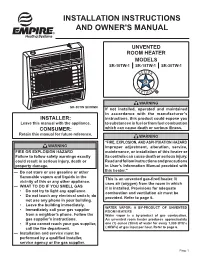

Installation INSTRUCTIONS and OWNER's MANUAL

Installation INSTRUCTIONS AND OWNER'S MANUAL UNVENTED ROOM HEATER MODELS SR-10TW-1 SR-18TW-1 SR-30TW-1 WARNING SR-30TW SHOWN If not installed, operated and maintained in accordance with the manufacturer’s INSTALLER: instructions, this product could expose you Leave this manual with the appliance. to substances in fuel or from fuel combustion CONSUMER: which can cause death or serious illness. Retain this manual for future reference. WARNING “FIRE, EXPLOSION, AND ASPHYXIATION HAZARD WARNING Improper adjustment, alteration, service, FIRE OR EXPLOSION HAZARD maintenance, or installation of this heater or Failure to follow safety warnings exactly its controls can cause death or serious injury. could result in serious injury, death or Read and follow instructions and precautions property damage. in User’s Information Manual provided with — Do not store or use gasoline or other this heater.” flammable vapors and liquids in the This is an unvented gas-fired heater. It vicinity of this or any other appliance. uses air (oxygen) from the room in which — WHAT TO DO IF YOU SMELL GAS it is installed. Provisions for adequate • Do not try to light any appliance. combustion and ventilation air must be • Do not touch any electrical switch; do provided. Refer to page 6. not use any phone in your building. • Leave the building immediately. WATER VAPOR: A BY-PRODUCT OF UNVENTED • Immediately call your gas supplier ROOM HEATERS from a neighbor’s phone. Follow the Water vapor is a by-product of gas combustion. gas supplier’s instructions. An unvented room heater produces approximately • If you cannot reach your gas supplier, one (1) ounce (30ml) of water for every 1,000 BTU’s call the fire department. -

From Disney to Disaster: the Disney Corporation’S Involvement in the Creation of Celebrity Trainwrecks

From Disney to Disaster: The Disney Corporation’s Involvement in the Creation of Celebrity Trainwrecks BY Kelsey N. Reese Spring 2021 WMNST 492W: Senior Capstone Seminar Dr. Jill Wood Reese 2 INTRODUCTION The popularized phrase “celebrity trainwreck” has taken off in the last ten years, and the phrase actively evokes specified images (Doyle, 2017). These images usually depict young women hounded by paparazzi cameras that are most likely drunk or high and half naked after a wild night of partying (Doyle, 2017). These girls then become the emblem of celebrity, bad girl femininity (Doyle, 2017; Kiefer, 2016). The trainwreck is always a woman and is usually subject to extra attention in the limelight (Doyle, 2017). Trainwrecks are in demand; almost everything they do becomes front page news, especially if their actions are seen as scandalous, defamatory, or insane. The exponential growth of the internet in the early 2000s created new avenues of interest in celebrity life, including that of social media, gossip blogs, online tabloids, and collections of paparazzi snapshots (Hamad & Taylor, 2015; Mercer, 2013). What resulted was 24/7 media access into the trainwreck’s life and their long line of outrageous, commiserable actions (Doyle, 2017). Kristy Fairclough coined the term trainwreck in 2008 as a way to describe young, wild female celebrities who exemplify the ‘good girl gone bad’ image (Fairclough, 2008; Goodin-Smith, 2014). While the coining of the term is rather recent, the trainwreck image itself is not; in their book titled Trainwreck, Jude Ellison Doyle postulates that the trainwreck classification dates back to feminism’s first wave with Mary Wollstonecraft (Anand, 2018; Doyle, 2017). -

The Client Community Nicolspdf III 2 Status Client

The Client Community NicolsPDF_III_2 Status Client Province Date No. Nomen Cognomen ? Aquae Sabaudiae Narbonensis 200 680 Smerius Masuetus ? Eburodunum Germ sup 150 292 Flavius Camillus ? Lepcis Afr proc 60 876 Rufus ? Lepcis Afr proc 60 877 Ignotus CA ? Reii Narbonensis 150 759 Ignotus AJ chec Auzia Mauretania 200 26 Aelius Longinus chec Sufetula Afr proc 732 check check city Verona Italia x 138 474 Nonius M. f. Mucianus citz ...enacates ? Pannonia 100 332 Glitius P. f. Atilius citz Abella Italia i 120 404 Marcius Plaetorius citz Abellinum Italia i 200 59 Antonius Rufinus citz Abellinum Italia i 225 183 Caesius T.f. Anthianus citz Abellinum Italia i 175 217 Claudius Frontinus citz Abellinum Italia i 175 218 Claudius Saethida citz Abellinum Italia i 175 219 Claudius Saethida citz Abellinum Italia i 200 278 Egnatius C. f. Certus citz Acinipo Baetica 225 378 Junius L. f. Terentianus citz Acinipo Baetica 200 422 Marius M. f. Fronto citz Acinipo Baetica 200 608 Servilius Q. f. Lupus citz Aeclanum Italia ii 126 277 Eggius L. f. Ambibulus citz Aeclanum Italia ii 150 468 Neratius C. f. Proculus citz Aeclanum Italia ii 161 509 Otacilius L. f. Rufus citz Aeclanum Italia ii 240 705 Calventius L f Corl...sinus? citz Aeclanum Italia ii 150 717 Maximus? citz Aeclanum Italia ii 150 795 Ignotus BF citz Aenona Dalmatia -1 615 Silius P. f. citz Aenona Dalmatia 23 678 Volusius L. f. Saturninus citz Aequicoli Italia iv 225 389 Livius Q. f. Velenius citz Aesernia Italia iv 150 1 Abullius Dexter citz Aesernia Italia iv -25 68 Appuleius Sex f citz Aesernia Italia iv 150 262 Decrius C. -

Shakespeare Unlimited: How King Lear Inspired Empire

Shakespeare Unlimited: How King Lear Inspired Empire Ilene Chaiken, Executive Producer Interviewed by Barbara Bogaev A Folger Shakespeare Library Podcast March 22, 2017 ---------------------------- MICHAEL WITMORE: Shakespeare can turn up almost anywhere. [A series of clips from Empire.] —How long you been plannin’ to kick my dad off the phone? —Since the day he banished me. I could die a thousand times… just please… From here on out, this is about to be the biggest, baddest company in hip-hop culture. Ladies and gentlemen, make some noise for the new era of Hakeem Lyon, y’all… MICHAEL: From the Folger Shakespeare Library, this is Shakespeare Unlimited. I‟m Michael Witmore, the Folger‟s director. This podcast is called “The World in Empire.” That clip you heard a second ago was from the Fox TV series Empire. The story of an aging ruler— in this case, the head of a hip-hop music dynasty—who sets his three children against each other. Sound familiar? As you will hear, from its very beginning, Empire has fashioned itself on the plot of King Lear. And that‟s not the only Shakespeare connection to the program. To explain all this, we brought in Empire’s showrunner, the woman who makes everything happen on time and on budget, Ilene Chaiken. She was interviewed by Barbara Bogaev. ---------------------------- BARBARA BOGAEV: Well, Empire seems as if its elevator pitch was a hip-hop King Lear. Was that the idea from the start? ILENE CHAIKEN: Yes, as I understand it, now I didn‟t create Empire— BOGAEV: Right, because you‟re the showrunner, and first there‟s a pilot, and then the series gets picked up, and then they pick the showrunner. -

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N. Purcell, 1997 Introduction The landscape of central Italy has not been intrinsically stable. The steep slopes of the mountains have been deforested–several times in many cases–with consequent erosion; frane or avalanches remove large tracts of regolith, and doubly obliterate the archaeological record. In the valley-bottoms active streams have deposited and eroded successive layers of fill, sealing and destroying the evidence of settlement in many relatively favored niches. The more extensive lowlands have also seen substantial depositions of alluvial and colluvial material; the coasts have been exposed to erosion, aggradation and occasional tectonic deformation, or–spectacularly in the Bay of Naples– alternating collapse and re-elevation (“bradyseism”) at a staggeringly rapid pace. Earthquakes everywhere have accelerated the rate of change; vulcanicity in Campania has several times transformed substantial tracts of landscape beyond recognition–and reconstruction (thus no attempt is made here to re-create the contours of any of the sometimes very different forerunners of today’s Mt. Vesuvius). To this instability must be added the effect of intensive and continuous intervention by humanity. Episodes of depopulation in the Italian peninsula have arguably been neither prolonged nor pronounced within the timespan of the map and beyond. Even so, over the centuries the settlement pattern has been more than usually mutable, which has tended to obscure or damage the archaeological record. More archaeological evidence has emerged as modern urbanization spreads; but even more has been destroyed. What is available to the historical cartographer varies in quality from area to area in surprising ways. -

Boardwalk Empire’ Comes to Harlem

ENTERTAINMENT ‘Boardwalk Empire’ Comes to Harlem By Ericka Blount Danois on September 9, 2013 “One looks down in secret and sees many things,” Dr. Valentin Narcisse (Jeffrey Wright) deadpans, speaking to Chalky White (Michael K. Williams). “You know what I saw? A servant trying to be a king.” And so begins a dance of power, politics and personality between two of the most electrifying, enigmatic actors on the television screen today. Each time the two are on screen—together or apart—they breathed new life into tonight’s premiere episode of Boardwalk Empire season four, with dark humor, slight smiles, powerful glances, smart clothes and killer lines. Entitled “New York Sour,” the episode opened with bombast, unlike the slow boil of previous seasons. Set in 1924, we’re introduced to the tasteful opulence of Chalky White’s new club, The Onyx, decorated with sconces custom-made in Paris and shimmering, shapely dancing girls. Chalky earned an ally, and eventually a partnership to be able to open the club, with former political boss and gangster Nucky Thompson (Steve Buscemi) by saving Nucky’s life last season. This sister club to the legendary Cotton Club in Harlem is Whites-only, but features Black acts. There are some cringe-worthy moments when Chalky, normally proud and infallible, has to deal with racism and bends over to appease his White clientele. But more often, Chalky—a Texas- born force to be reckoned with—breathes an insistent dose of much needed humor into what sometimes devolves into cheap shoot ’em up thrills this season. The meeting of the minds between Narcisse and Chalky takes root in the aftermath of a mistake by Chalky’s right hand man, Dunn Purnsley (Erik LaRay Harvey), who engages in an illicit interracial tryst that turns out to be a dramatic, racially-charged sex game gone horribly wrong. -

Redalyc.SUGAR, EMPIRE, and REVOLUTION in EASTERN CUBA

Caribbean Studies ISSN: 0008-6533 [email protected] Instituto de Estudios del Caribe Puerto Rico Casey, Matthew SUGAR, EMPIRE, AND REVOLUTION IN EASTERN CUBA: THE GUANTÁNAMO SUGAR COMPANY RECORDS IN THE CUBAN HERITAGE COLLECTION Caribbean Studies, vol. 42, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2014, pp. 219-233 Instituto de Estudios del Caribe San Juan, Puerto Rico Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=39240402008 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative SUGAR, EMPIRE, AND REVOLUTION IN EASTERN CUBA... 219 SUgAR, EMPIRE, AND REVOLUTION IN EASTERN CUBA: ThE gUANTáNAMO SUgAR COMPANy RECORDS IN ThE CUBAN hERITAgE COLLECTION Matthew Casey ABSTRACT The Guantánamo Sugar Company Records in the Cuban Heritage Col- lection at the University of Miami represent some of the only accessible plantation documents for the province of Guantánamo in republican Cuba. Few scholars have researched in the collection and there have not been any publications to draw from it. Such a rich collection allows scholars to tie the province’s local political, economic, and social dynamics with larger national, regional, and global processes. This is consistent with ongoing scholarly efforts to understand local and global interactions and to pay more attention to regional differences within Cuba. This research note uses the records to explore local issues of land, labor, and politics in republican-era Guantánamo in the context of larger national and international processes. -

Matthew J. Blevins, Vice President, Empire Stock Transfer Inc

\JHf Empire Stock Transfer Inc. 1859 Whitney Mesa Dr. Henderson, NV 89014 KECEIVED January 15,2014 JAN 16 2014 Elizabeth M. Murphy OFFICbOHHESFrpcTi.gg Secretary U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 100 F Street, NE Washington, DC 20549 Dear Ms. Murphy: Today I am responding on behalf of Empire Stock Transfer Inc. with respect to the Securities and Exchange Commission's Crowdfunding rule proposal, Release Nos. 33-9470; 34-70741; File No. S7-09-13. " The Securities and Exchange Commission, the "Commission", is proposing for comment new Regulation Crowdfunding under the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 to implement the requirements of Title III of the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act. Regulation Crowdfunding would prescribe rules governing the offer and sale of securities under new Section 4(a)(6) ofthe Securities Act of 1933. The proposal also would provide a framework for the regulation of registered funding portals and brokers that issuers are required to use as intermediaries in the offer and sale of securities in reliance on Section 4(a)(6). In addition, the proposal would exempt securities sold pursuant to Section 4(a)(6) from the registration requirements ofSection 12(g) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Empire Stock Transfer Inc., "Empire", is a stock transfer agent with operations in the United States. Our clients, whom are primarily small-cap issuers, are located throughout the world. Empire assists private startups as well as publicly-traded companies in their efforts to maintain a compliant and healthy shareholder relationship. How does the Commission view a transfer agent? http://www.sec.gov/divisions/marketreg/mrtransfer.shtml Transfer agents record changes of ownership, maintain the issuer's security holder records, cancel and issue certificates, and distribute dividends. -

Tinashe Flame Release

RELEASES NEW SINGLE “FLAME” “FLAME” IS AVAILABLE TODAY ON ALL PLATFORMS TINASHE SET FOR GUEST STARRING ROLE ON THE NEW SEASON OF EMPIRE, NAMED PEPSI’S SOUND DROP ARTIST EARNS ANOTHER BILLBOARD #1 WITH BRITNEY SPEARS COLLABORATION “SLUMBER PARTY” ON THE DANCE CHARTS March 16, 2017 – Los Angeles, CA – Platinum selling singer, songwriter, producer and entertainer Tinashe releases her brand new single today, “Flame.” The track, which was produced by Sir Nolan, is available at all digital retail and streaming partners. Listen to “Flame” iTunes/Apple Music: http://smarturl.it/iFlame Spotify: http://smarturl.it/spFlame Vevo: http://smarturl.it/pvFlame Amazon Music: http://smarturl.it/azFlame Google Play: http://smarturl.it/gpFlame The release of “Flame” follows on the heels of Tinashe’s critically acclaimed Nightride project, released late last year. The 14-track project, a companion piece to her upcoming studio album, includes stand-out track “Company.” The song recently received an attention-grabbing video clip, a full-on dance assault, all done in one take. To view the video for “Company,” click here. Nightride is the first of a two-part series, which will include Tinashe’s sophomore studio album, Joyride. With the projects representing two different sides of Tinashe, “Flame” is taken from the latter. Tinashe told Rolling Stone, “I see them as two things that are equally the same. I think you can be a combination of things, and that's what makes people human and complex. They are equally me. I don't like to be limited to one particular thing so I want to represent that duality and that sense of boundlessness in my art." As a go-to collaborator and hit maker, Tinashe has also recently appeared on tracks with the likes of Britney Spears, Davido, Tinie Tempah, Enrique Iglesias, KDA and Lost Kings.