Identifying Land Acquisition Strategies for Simcoe County Forests a Review of Securement Strategies in Ontario

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolving Muskoka Vacation Experience 1860-1945 by Geoffrey

The Evolving Muskoka Vacation Experience 1860-1945 by Geoffrey Shifflett A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2012 © Geoffrey Shifflett 2012 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation examines the development of tourism in Muskoka in the Canadian Shield region from 1860 to 1945. Three key themes are examined: the tourists, the resorts and projected image of the area. When taken together, they provide insight into the origin and evolution of the meanings attached to tourist destinations in the Canadian Shield. The Muskoka Lakes region provides the venue in which continuity and change in each of these elements of the tourism landscape are explored. This dissertation uses previously underutilized primary source materials ranging from hotel ledgers, financial reports, personal correspondence, period brochures, guidebooks, and contemporary newspaper articles to reconstruct the Muskoka tourist experience over an extended period of time. The volume of literature pertaining to American tourism history significantly outweighs similar work conducted on Canadian destinations. This dissertation, therefore, begins with an overview of key works related to the historical development of tourism in the United States followed by a survey of corresponding Canadian literature. The lack of an analytical structure in many tourist historical works is identified as a methodological gap in the literature. -

Rank of Pops

Table 1.3 Basic Pop Trends County by County Census 2001 - place names pop_1996 pop_2001 % diff rank order absolute 1996-01 Sorted by absolute pop growth on growth pop growth - Canada 28,846,761 30,007,094 1,160,333 4.0 - Ontario 10,753,573 11,410,046 656,473 6.1 - York Regional Municipality 1 592,445 729,254 136,809 23.1 - Peel Regional Municipality 2 852,526 988,948 136,422 16.0 - Toronto Division 3 2,385,421 2,481,494 96,073 4.0 - Ottawa Division 4 721,136 774,072 52,936 7.3 - Durham Regional Municipality 5 458,616 506,901 48,285 10.5 - Simcoe County 6 329,865 377,050 47,185 14.3 - Halton Regional Municipality 7 339,875 375,229 35,354 10.4 - Waterloo Regional Municipality 8 405,435 438,515 33,080 8.2 - Essex County 9 350,329 374,975 24,646 7.0 - Hamilton Division 10 467,799 490,268 22,469 4.8 - Wellington County 11 171,406 187,313 15,907 9.3 - Middlesex County 12 389,616 403,185 13,569 3.5 - Niagara Regional Municipality 13 403,504 410,574 7,070 1.8 - Dufferin County 14 45,657 51,013 5,356 11.7 - Brant County 15 114,564 118,485 3,921 3.4 - Northumberland County 16 74,437 77,497 3,060 4.1 - Lanark County 17 59,845 62,495 2,650 4.4 - Muskoka District Municipality 18 50,463 53,106 2,643 5.2 - Prescott and Russell United Counties 19 74,013 76,446 2,433 3.3 - Peterborough County 20 123,448 125,856 2,408 2.0 - Elgin County 21 79,159 81,553 2,394 3.0 - Frontenac County 22 136,365 138,606 2,241 1.6 - Oxford County 23 97,142 99,270 2,128 2.2 - Haldimand-Norfolk Regional Municipality 24 102,575 104,670 2,095 2.0 - Perth County 25 72,106 73,675 -

Watershed Award Winners 1

THE GRAND STRATEGY NEWSLETTER Volume 11, Number 2 - March/April 2006 Grand River The Grand: Conservation A Canadian Authority Heritage River Features Watershed Award winners 1 Milestones Workshop addresses value of heritage 4 What's Happening Program aims to conserve natural areas 5 Brantford-Brant water Watershed Award winners festival new this year 5 ach year the Grand River Conservation This article, adapted from the script for the EAuthority recognizes the efforts of individu- show, highlights four winners of Watershed Now available als and groups by presenting awards for out- Awards. The other winners were featured in the standing examples of conservation and environ- previous edition of Grand Actions. Shunpiking in mental work. Waterloo Region 6 For 2005, the winner of the Honour Roll Hillside Festival, Guelph Award is S.C. Johnson and Son Ltd. of Brantford. Look Who’s The winners of the Watershed Awards are Hillside Festival has grown over the past 21 Taking Action Waterloo Region District School Board and years from a small, 11-hour festival to a three day event attracting 5,000 people a day. County of Brant Waterloo Catholic District School Board; It’s on the island at Guelph Lake Conservation preserves bridge 7 Greentec International Inc., Cambridge; Wilfrid Laurier/Mohawk Environmental Group, Area when the island’s quiet tranquility is trans- formed into a hub of activity. Sold out for the Grand Strategy Brantford; Hillside Festival, Guelph; John first time in 2005, it featured 45 bands. Calendar 8 Jackson of Kitchener, founder of the Great Lakes United; Vlad Jelinek, Rosewood Farm, Grand Music brings in the crowd, but Hillside is Cover photo Valley; and Arnold VerVoort and Family farm, much more than music. -

GWTA 2019 Overview and Participant Survey Monday, August 26, 2019

GWTA 2019 Overview and Participant Survey Monday, August 26, 2019 Powered by Cycle the North! GWTA 2019-July 28 to August 2 450km from Sault Ste. Marie to Sudbury launching the Lake Huron North Channel Expansion of the Great Lakes Waterfront Trail and Great Trail. Overnight Host Communities: Sault Ste. Marie, Bruce Mines, Blind River, Espanola, Sudbury Rest Stop Hosts: Garden River First Nation, Macdonald Meredith and Aberdeen Additional (Echo Bay), Johnson Township (Desbarats), Township of St. Joseph, Thessalon, Huron Shores (Iron Bridge), Mississauga First Nation, North Shore Township (AlgoMa Mills), Serpent River First Nation, Spanish, Township of Spanish-Sables (Massey), Nairn Centre. 150 participants aged 23 to 81 coming from Florida, Massasschutes, Minnesota, New Jersey, Arizona, and 5 provinces: Ontario (91%), British ColuMbia, Alberta, Quebec and New Brunswick. 54 elected representatives and community leaders met GWTA Honorary Tour Directors and participants at rest stops and in soMe cases cycled with the group. See pages 24-26 for list. Special thanks to our awesome support team: cycling and driving volunteers, caMp teaM, Mary Lynn Duguay of the Township of North Shore for serving as our lead vehicle and Michael Wozny for vehicle support. Great regional and local Media coverage. 2 The Route—Lake Huron North Channel Expansion—450 km from Gros Cap to Sudbury Gichi-nibiinsing-zaaga’igan Ininwewi-gichigami Waaseyaagami-wiikwed Naadowewi-gichigami Zhooniyaang-zaaga’igan Gichigami-zitbi Niigani-gichigami Waawiyaataan Waabishkiigoo-gichigami • 3000 km, signed route The Lake Huron North Channel celebrates the spirit of the North, following 12 heritage• 3 rivers,Great Lakes,connecting 5 bi- nationalwith 11 northern rivers lakes, • 140 communities and First Nations winding through forests, AMish and Mennonite farmland, historic logging, Mining and• fishing3 UNESCO villages, Biospheres, and 24 beaches. -

Stage 2 Archaeological Assessment

ORIGINAL REPORT Stage 2 Archaeological Assessment of Residential Lots Proposed on Part of Lots 2, 3, & 4, Concession 9 Part of Lots 2, 3, 4 & 5 Concession 8 Geographic Township of Radcliffe Township of Madawaska Valley County of Renfrew in northcentral Ontario. Report Author: Dave Norris Woodland Heritage Northwest 134 College St. Thunder Bay, ON P7A 5J5 p: (807) 632-9893 e: [email protected] Project Information Location: Lot 2 and 3 CON 8 and Lots 2 and 3 CON 9 of the Township of Madawaska Valley PIF P307-0077-2017 Proponent Information: Mr. Neil Enright National Fur Farms Inc. 118 Annie Mayhew Road Combermere, Ontario K0J 1L0 Tel: (480) 363-6558 E-Mail: [email protected] Report Completed: September 13, 2017 Report Submitted: October 1, 2017 Stage 2 Archaeological Assessment of Lots 2 and 3 CON8, Lots 2 and 3 CON 9 in the Township of Madawaska Valley, Township of Renfrew i © 2017 Woodland Heritage Northwest. All rights reserved. Executive Summary National Fur Farms Inc. in Combermere, Ontario contracted Woodland Heritage Services to conduct a Stage 1 Archaeological Assessment of their property located on Part of Lots 2, 3 and 4 CON 9 and Lots 2, 3, 4 and 5 CON 8 of the Township of Madawaska Valley, in the county of Renfrew in northcentral Ontario. The proponent is planning on subdividing the property into 60 residential lots. The archaeological assessment was undertaken in accordance with the requirements of the Ontario Heritage Act (R.S.O. 1990), the Planning Act, and the Standards and Guidelines for Consulting Archaeologists (2011). -

Aboriginal Presence in Our Schools

District School Board Ontario North East Aboriginal Presence in Our Schools A Guide for Staff District School Board Ontario North East Revised 2014 Aboriginal Presence in Our Schools ii District School Board Ontario North East Table of Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................ vi Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... vii Supporting Aboriginal Students in DSB Ontario North East ............................................................. 1 First Nations Trustee ....................................................................................................................... 1 First Nations Advisory Committee ................................................................................................. 1 Voluntary Self-Identification .......................................................................................................... 1 Aboriginal Youth Liaison Officers ................................................................................................. 2 Aboriginal Presence in Our Schools ................................................................................................... 3 Ensuring Success for Schools ............................................................................................................. 3 Terminology ....................................................................................................................................... -

THE CHRONOLOGICAL POSITION of the CRS SITE, SIMCOE COUNTY, ONTARIO David R. Bush

Bush: THE CRS SITE 17 THE CHRONOLOGICAL POSITION OF THE CRS SITE, SIMCOE COUNTY, ONTARIO David R. Bush ABSTRACT Through the application of the coefficient of similarity test (Emerson, 1966, 1968) on the ceramics excavated from the CRS site, the chronological position and cultural affiliation of this site was established. The ceramic vessel and pipe analyses of the recovered materials indicate the site to be a very Late Prehistoric Huron village occupied between A.D. 1550 and A.D. 1580. INTRODUCTION The preliminary excavation of the CRS site (from 1968-1973) was undertaken with the hopes of establishing the site's proper cultural and temporal position. Further studies of cultural processes could then proceed once the cultural and chronological position of the CRS site was evaluated. It has been the aim of this research to utilize the coefficient of similarity test as one method of determining the chronological placement and cultural affiliation of this site. The following is the study of the ceramics excavated from the CRS site. Simcoe County, Ontario (Figure 1, taken from Emerson, 1968, p. 63). SITE DESCRIPTION The exact location of the CRS site has been withheld by personal request of the landowner. The site lies approximately one-half mile east of Hog Creek and approximately 3-1 /2 miles south of Sturgeon Bay. The site sits within the 900 foot contour line about 320 feet above the water level of Georgian Bay. Within a 2 mile radius of the site the soils are generally deep, moderately well drained, and have a good water holding capacity. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 Office of the Ombudsman of Ontario 483 Bay Street 10Th Floor, South Tower Toronto, Ontario M5G 2C9

ONTA RIO ONTARIO’S WATCHDOG ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 Office of the Ombudsman of Ontario 483 Bay Street 10th Floor, South Tower Toronto, Ontario M5G 2C9 Telephone: 416-586-3300 Complaints line: 1-800-263-1830 Fax: 416-586-3485 TTY: 1-866-411-4211 Website: www.ombudsman.on.ca @Ont_Ombudsman Ontario Ombudsman OntarioOmbudsman OntOmbuds ISSN 1708-0851 ONTA RIO ONTARIO’S WATCHDOG June 2020 Hon. Ted Arnott, Speaker Legislative Assembly Province of Ontario Queen’s Park Dear Mr. Speaker, I am pleased to submit my Annual Report for the period of April 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020, pursuant to section 11 of the Ombudsman Act, so that you may table it before the Legislative Assembly. Sincerely, Paul Dubé Ombudsman Office of the Ombudsman of Ontario 483 Bay Street 10th Floor, South Tower Toronto, Ontario M5G 2C9 Telephone: 416-583-3300 Complaints line: 1-800-263-1830 Website: www.ombudsman.on.ca Office of the Ombudsman of Ontario • 2019-2020 Annual Report 1 2 Office of the Ombudsman of Ontario • 2019-2020 Annual Report YEAR IN REVIEW • TEXT TABLE OF CONTENTS OMBUDSMAN’S MESSAGE .........................................................................................................5 2019-2020 AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................8 ABOUT OUR OFFICE .................................................................................................................10 HOW WE WORK .........................................................................................................................................................................12 -

Understanding the Lived Experiences of Local Residents in Muskoka, Ontario: a Case Study on Cottaging

Understanding The Lived Experiences of Local Residents in Muskoka, Ontario: A Case Study on Cottaging by Ashley Gallant A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Recreation and Leisure Studies (Tourism) Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2017 © Ashley Gallant 2017 A AUTHORS DECLARATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii ABSTRACT Muskoka, Ontario, Canada has been recognized as an environment that is appealing for tourism visitation, but more specially cottaging, due to its attractive natural landscape and amenities that are “normally associated with larger cities, while maintaining the lifestyle of a small community” (The District Municipality of Muskoka, 2014). Specifically, for four months of the year, 83, 203 seasonal residents outnumber their 59, 220 permanent counterparts, cultivating a variety of opportunities and challenges in the destination. This particular study, aims to look at tourism in Muskoka in regard to its enhancement of social, economic, and political assets in the destination, and how cottaging impacts the local community from the viewpoint of the permanent resident. Current issues and tensions that exist in Muskoka are drawn upon through secondary data analysis of media articles, government documents, opinion pieces, and 16 semi-structured -

OMERS Employer Listing (As at December 31, 2020)

OMERS Employer Listing (As at December 31, 2020) The information provided in this chart is based on data provided to the OMERS Administration Corporation and is current until December 31, 2020. There are 986 employers on this listing with a total of 288,703 active members (30,067 NRA 60 active members and 258,636 NRA 65 active members). Are you looking for a previous employer to determine your eligibility for membership in the OMERS Primary Pension Plan? If you think your previous employer was an OMERS employer but you don’t see it on this list, contact OMERS Client Services at 416-369-2444 or 1-800-387-0813. Your previous employer could be related to or amalgamated with another OMERS employer and not listed separately here. Number of Active Members Employer Name NRA 60 NRA 65 Total 1627596 ONTARIO INC. * * 519 CHURCH STREET COMMUNITY CENTRE 48 48 AJAX MUNICIPAL HOUSING CORPORATION * * AJAX PUBLIC LIBRARY BOARD 42 42 ALECTRA ENERGY SERVICES * * ALECTRA ENERGY SOLUTIONS INC. * * ALECTRA INC. * * ALECTRA POWER SERVICES INC. * * ALECTRA UTILITIES CORPORATION 1,283 1,283 ALGOMA DISTRICT SCHOOL BOARD 522 522 ALGOMA DISTRICT SERVICES ADMINISTRATION BOARD 120 120 ALGOMA HEALTH UNIT 178 178 ALGOMA MANOR NURSING HOME 69 69 ALGONQUIN AND LAKESHORE CATHOLIC DISTRICT SCHOOL BOARD 558 558 ALMISE CO-OPERATIVE HOMES INC. * * ALSTOM TRANSPORT CANADA 45 45 APPLEGROVE COMMUNITY COMPLEX * * ART GALLERY OF BURLINGTON * * ASSOCIATION OF MUNICIPAL MANAGERS, CLERKS AND TREASURERS OF * * ONTARIO ASSOCIATION OF MUNICIPALITIES OF ONTARIO 42 42 ATIKOKAN HYDRO INC * * AU CHATEAU HOME FOR THE AGED 214 214 AVON MAITLAND DISTRICT SCHOOL BOARD 745 745 AYLMER POLICE SERVICES BOARD * * * BELLEVILLE PUBLIC LIBRARY BOARD 29 29 * at least one of NRA 60 or NRA 65 number of active members is less than 25 The information is used for pension administration purposes, and may not be appropriate for other purposes, and is current to December 31, 2020. -

History of the Simcoe County Region Indigenization Column: May 17, 2017

History of the Simcoe County Region Indigenization Column: May 17, 2017 If anyone has been to the Simcoe County Museum on Highway 26, they will have seen the beautiful Huron-Wendat artifacts and replica longhouse they have on permanent display. With all the discussion around Anishnaabeg (Ojibwe people) and the Anishnaabemowin (Ojibwe language) program, many may be confused as to why there are different nations in the same region. Hopefully, I can shed some light on this question. This region was once inhabited by the Huron-Wendat nations, until about 350 years ago. The Huron- Wendat are a confederacy of five Haudenosaunee-speaking (Iroquois) nations. They are the; Attinniaoenten ("people of the bear"), Hatingeennonniahak ("makers of cords for nets"), Arendaenronnon ("people of the lying rock"), Atahontaenrat ("two white ears" i.e., “deer people”) and Ataronchronon ("people of the bog"). These nations had once been as far south as the Virginias and Ohio Valley, but had settled in this region pre-contact. These nations came into contact with the French settlers in the early 1600s, and it was this contact that caused a great deal of epidemics such as measles, influenza, and smallpox amongst the nations. The term ‘Huron’ comes from a demeaning nickname for the nation, which means ‘boar’s head’ in French and was used in reference to ruffians. The Wendat were enemies of the five Haudenosaunee nations (later joined by the Tuscarora in 1722 and became the Six Nations we know today). By the mid-1600s the Wendat population had been reduced by half, from approximately 20,000 to 9,000 by the epidemics brought by the French settlers living in close quarters with the nations. -

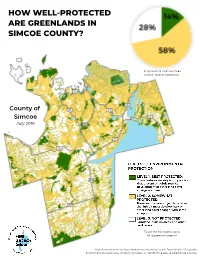

How Well-Protected Are Greenlands in Simcoe County?

HOW WELL-PROTECTED ARE GREENLANDS IN SIMCOE COUNTY? Proportion of total land area in each 'level of protection'. County of Simcoe July 2019 To see the full legend, go to bit.ly/greenlandsreport. Map produced by Assim Sayed Mohammed and Kirby Calvert, Department of Geography, Environment and Geomatics, University of Guelph, on behalf of the Rescue Lake Simcoe Coalition. HOW WELL-PROTECTED ARE GREENLANDS IN SIMCOE COUNTY? The Rescue Lake Simcoe Coalition’s greenlands[i] mapping project seeks to identify how well- protected Simcoe County forests, wetlands and shorelines are by analyzing the strength of the policies that protect them, and mapping the results of our findings. Cartographers created four maps for this research, showing the land use mix in Simcoe County, the breakdown of the levels of protection, the locations of aggregate resources that could eat into the best protected greenlands if extraction were permitted, and the features identified in our “Best Protected” category. What should we have? Forest cover 50% forest cover or more of the watershed is likely to support most potential species, and healthy aquatic systems.[ii] Simcoe County has 22%, but is losing forest cover. Wetlands The greater of (a) 10% of each major watershed and 6% of each subwatershed, or (b) 40% of the historic watershed wetland coverage, should be protected and restored, and no net loss of wetlands. [iii] Simcoe County has 14% wetland cover based on our analysis, and approximately half of its historic wetland cover.[iv] Simcoe County is losing wetlands. [v] Simcoe County’s land use mix does not meet ideal greenlands protection targets, but it is possible to get it right in Simcoe County, and permanently protect an effective Natural Heritage System to buffer our waters and ecosystem from the impacts of climate change and development.