From Class Action to Reparative Philanthropy: the Norflet Progress Fund and the Future of Cy Pres

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Political Economy of Colorblindness: Neoliberalism and the Reproduction of Racial Inequality in the United States

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF COLORBLINDNESS: NEOLIBERALISM AND THE REPRODUCTION OF RACIAL INEQUALITY IN THE UNITED STATES A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University By Phillip A. Hutchison Master of Arts University of California, Los Angeles, 2002 Director: Paul Smith, Professor Cultural Studies Fall Semester 2010 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright: 2010 Phillip A. Hutchison All Rights Reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract ............................................................................................................................. iv Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 Literature Review............................................................................................................. 30 Chapter 1 .......................................................................................................................... 69 Chapter 2 .......................................................................................................................... 94 Chapter 3 ........................................................................................................................ 138 Chapter 4 ........................................................................................................................ 169 Chapter 5 ....................................................................................................................... -

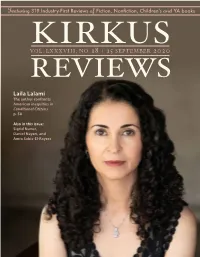

Kirkus Reviews on Our Website by Logging in As a Subscriber

Featuring 319 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books VOL.KIRKUS LXXXVIII, NO. 18 | 15 SEPTEMBER 2020 REVIEWS Laila Lalami The author confronts American inequities in Conditional Citizens p. 58 Also in this issue: Sigrid Nunez, Daniel Nayeri, and Amra Sabic-El-Rayess from the editor’s desk: The Way I Read Now Chairman BY TOM BEER HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # Among the many changes in my daily life this year—working from home, Chief Executive Officer wearing a mask in public, watching too much TV—my changing read- MEG LABORDE KUEHN ing habits register deeply. For one thing, I read on a Kindle now, with the [email protected] Editor-in-Chief exception of the rare galley sent to me at home and the books I’ve made TOM BEER a point of purchasing from local independent bookstores or ordering on [email protected] Vice President of Marketing Bookshop.org. The Kindle was borrowed—OK, confiscated—from my SARAH KALINA boyfriend at the beginning of the pandemic, when I left dozens of advance [email protected] reader copies behind at the office and accepted the reality that digital gal- Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU leys would be a practical necessity for the foreseeable future. I can’t say that I [email protected] love reading on my “new” Kindle—I’m still a sucker for physical books after Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK all these years—but I’ll admit that it fulfills its purpose efficiently. And I do [email protected] Tom Beer rather enjoy the instant gratification of going on NetGalley or Edelweiss Young Readers’ Editor VICKY SMITH and dispatching multiple books to my device in one fell swoop—a harmless [email protected] form of bingeing that affords a little dopamine rush. -

Righting the Wrongs of Slavery, 89 Geo. LJ 2531

UIC School of Law UIC Law Open Access Repository UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2001 Forgive U.S. Our Debts? Righting the Wrongs of Slavery, 89 Geo. L.J. 2531 (2001) Kevin Hopkins John Marshall Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs Part of the Law and Race Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Kevin Hopkins, Forgive U.S. Our Debts? Righting the Wrongs of Slavery, 89 Geo. L.J. 2531 (2001). https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs/153 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVIEW ESSAY Forgive U.S. Our Debts? Righting the Wrongs of Slavery KEvIN HOPKINS* "We must make sure that their deaths have posthumous meaning. We must make sure that from now until the end of days all humankind stares this evil in the face.., and only then can we be sure it will never arise again." President Ronald Reagan' INTRODUCTION: Tm BIG PAYBACK In recent months, claims for reparations for slavery have gained new popular- ity amongst black intellectuals and trial lawyers and have been given additional momentum by the publication of Randall Robinson's controversial and thought- provoking book, The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks.2 In The Debt, Robinson makes a serious and persuasive case for the payment of reparations by the United States government to African-Americans for both the injustices done to their ancestors during slavery and the effect of those wrongs on the current * Associate Professor of Law, The John Marshall Law School. -

Joined with Several Organizations

November 17, 2015 The Honorable Loretta E. Lynch Attorney General of the United States United States Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20530‐0001 RE: REQUEST FOR FEDERAL INVESTIGATION IN ORANGE COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Dear Attorney General Lynch: We the undersigned share a firm belief in our criminal justice system and its overall ability to produce fair and reliable results. Compelling evidence of pervasive police and prosecutorial misconduct in Orange County, however, has caused us grave concern. We write to urge the Department of Justice to initiate an investigation into the actions of the Orange County Sheriff’s Department (“OCSD”) and the Orange County District Attorney’s Office (“OCDA”) in connection with the use of jailhouse informants and the concealment of informant‐related evidence. EVIDENCE OF MISCONDUCT IN ORANGE COUNTY: AN OVERVIEW On September 30, 2015, The New York Times published an editorial addressing the situation in Orange County, which stated, in part: In a scheme that may go back as far as 30 years, prosecutors and the county sheriff’s department have elicited illegal jailhouse confessions, failed to turn over evidence that is favorable to defendants and lied repeatedly in court about what they did . Among other things, the defense argued, deputies intentionally placed informants in cells next to defendants facing trial . and hid that fact. The informants, some of whom faced life sentences for their own crimes, were promised reduced sentences or cash payouts in exchange for drawing out confessions or other incriminating evidence from the defendants. This practice is prohibited once someone has been charged with a crime. -

The Story Behind a Letter in Support of Professor Derrick Bell

1-1-2014 The Story Behind a Letter in Support of Professor Derrick Bell Margaret E. Montoya University of New Mexico - School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/law_facultyscholarship Part of the Law and Gender Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Margaret E. Montoya, The Story Behind a Letter in Support of Professor Derrick Bell, 75 University of Pittsburgh Law Review 1 (2014). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/law_facultyscholarship/234 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the UNM School of Law at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH LAW REVIEW Vol. 75 ● Summer 2014 THE STORY BEHIND A LETTER IN SUPPORT OF PROFESSOR DERRICK BELL Cheryl Nelson Butler, Sherrilyn Ifill, Suzette Malveaux, Margaret E. Montoya, Natsu Taylor Saito, Nareissa L. Smith and Tanya Washington ISSN 0041-9915 (print) 1942-8405 (online) ● DOI 10.5195/lawreview.2014.353 http://lawreview.law.pitt.edu This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. This site is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D- Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2712505 THE STORY BEHIND A LETTER IN SUPPORT OF PROFESSOR DERRICK BELL Cheryl Nelson Butler, Sherrilyn Ifill, Suzette Malveaux, Margaret E. -

On Being a Black Lawyer 2013 Power

2013 SALUTES THE MOSTBLACK INFLUENTIAL LAWYERS IN THE NATION 100 AND DIVERSITY ADVOCATES CONGRATULATIONS TO OUR POWER 100 HONOREES WE SALUTE OUR AFRICAN AMERICAN PARTNERS We salute Chief Diversity Officer Theresa Cropper and Firmwide Executive Committee Chair Laura Neebling for being recognized as Power 100 honorees. As a Pipeline Builder, Ms. Cropper has invested in the diversity pipeline throughout her career and prepared students at every level to pursue their dreams. As an Advocate, Ms. Neebling has championed diversity and inclusion at the firm and lent her leadership to initiatives that advance the cause. Perkins Coie is proud of their contributions and extends warmest congratulations to them both. ALLEN CANNON III DENNIS HOPKINS SEAN KNOWLES RICHARD ROSS Government Contracts, Washington, D.C. Commercial Litigation, New York Commercial Litigation, Seattle Business, New York PHILIP THOMPSON LINDA WALTON JAMES WILLIAMS BOBBIE WILSON Labor, Bellevue Labor, Seattle Commercial Litigation, Seattle Commercial Litigation, San Francisco THERESA CROPPER LAURA NEEBLING Chief Diversity Officer Chair, Firmwide Executive Committee At Perkins Coie, we believe that diversity is a key ingredient to success. We benefit from diverse perspectives that allow us to deliver excellent counsel to our clients. At Perkins Coie, Diversity is a Key Ingredient. We support On Being a Black Lawyer in recognizing the contributions of the Power 100 (2013) honorees. ANCHORAGE · BEIJING · BELLEVUE · BOISE · CHICAGO · DALLAS · DENVER ANCHORAGE · BEIJING · BELLEVUE · BOISE · CHICAGO · DALLAS · DENVER LOS ANGELES · MADISON · NEW YORK · PALO ALTO · PHOENIX · PORTLAND LOS ANGELES · MADISON · NEW YORK · PALO ALTO · PHOENIX · PORTLAND SAN DIEGO · SAN FRANCISCO · SEATTLE · SHANGHAI · TAIPEI · WASHINGTON, D.C. SAN DIEGO · SAN FRANCISCO · SEATTLE · SHANGHAI · TAIPEI · WASHINGTON, D.C. -

In Response to a Proposal from Pipeline

PipelinePipeline CrisisCrisis WinningWWinninginning StrategiesSStrategiestrategies ClosingClosing thethe SocialSocial && EconomicEconomic DivideDivide forfforor YoungYYoungoung BlackBBlacklack MenMenMen ThirdThird PlenaryPlenary SessionSession Friday,Friday, JulyJuly 11,11, 20082008 PierPier SixtySixty atat ChelseaChelsea PiersPiers NewNew YorkYork 1 2 Pipeline Crisis Winning Strategies Closing the Social & Economic Divide for Young Black Men Third Plenary Session Friday, July 11, 2008 Pier Sixty at Chelsea Piers New York TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome ..........................................................................................6-11 Agenda ................................................................................................ 13 Biographies ...................................................................................15-27 Award Presenters ........................................................................29-33 Honorees .......................................................................................35-41 Acknowledgments .......................................................................42-49 5 WELCOME Welcome to the third plenary session of the Pipeline Crisis/Winning Strategies initiative on young black men. The Initiative From a modest start two years ago, this initiative has become a broad-based collaborative committed to closing the stark divide between America’s promise and the social, economic and political realities of young black men. The initiative seeks to stimulate opportunities for the -

Lani Guinier's Nomination President's Column

SALT Volume 1993, Issue 3 Society of American Law Teachers September 1993 LANI GUINIER'S PRESIDENT'S COLUMN NOMINATION - Sylvia A. Law - Phoebe A. Haddon New York University Temple University School of Law School of Law Salt Goes to Washington During the weeks before President Clin- ton withdrew Lani Guinier's nomination, SALT members working with the new there was a flurry of activity supporting her administration have experienced at least one candidacy as many of us realized that he grievous defeat and a number of successes. might actually bow to the pressure from SALT, and many of its members, vigorously right-wing activists and abandon her. In the contested the conservative mischaracteriza- midst of this mounting activism, on the day tion of Lani Guinier's work and the cowardly after Lani broke the Administration-imposed refusal of the Administration and the Senate silence in response to her attackers by appear- Judiciary Committee to allow her the oppor- ing on Nightline, President Clinton did for- tunity to publicly defend herself. Phoebe sake his friend, refusing to provide the public Haddon's companion column on this page and Lani an officially-sanctioned opportunity underscores our anger and deep disappoint- to speak her mind and respond to her oppo- ment at the wrong done to Professor Guinier. nents. For many people, particularly women Still, we are proud of and pleased about and people of color who were enlisted into ac- SALT members who have gone to Washing- tion as the controversy mounted over Lani's ton to help the new Administration tackle the nomination, this refusal was unconscionable. -

Parsing the Plagiary Scandals in History and Law

The University of New Hampshire Law Review Volume 5 Number 3 Pierce Law Review Article 3 June 2009 Parsing the Plagiary Scandals in History and Law Arthur Austin Case Western Reserve University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/unh_lr Part of the Higher Education Commons, History Commons, Other Communication Commons, and the Other Rhetoric and Composition Commons Repository Citation Arthur Austin, Parsing the Plagiary Scandals in History and Law, 5 Pierce L. Rev. 367 (2007), available at http://scholars.unh.edu/unh_lr/vol5/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce School of Law at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The University of New Hampshire Law Review by an authorized editor of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Parsing the Plagiary Scandals in History and Law ARTHUR AUSTIN ∗ I. INTRODUCTION In 2002 the history of History was scandal. The narrative started when a Pulitzer Prize winning professor was caught foisting bogus Vietnam War exploits as background for classroom discussion.1 His fantasy lapse pref- aced a more serious irregularity—the author of the Bancroft Prize book award was accused of falsifying key research documents.2 The award was rescinded. The year reached a crescendo with two plagiarism cases “that shook the history profession to its core.”3 Stephen Ambrose and Doris Kearns Goodwin were “crossover” celeb- rities: esteemed academics—Pulitzer winners—with careers embellished by a public intellectual reputation. -

Reading Professor Obama: Race and the American Constitutional Tradition

UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH LAW REVIEW Vol. 75 ● Summer 2014 READING PROFESSOR OBAMA: RACE AND THE AMERICAN CONSTITUTIONAL TRADITION Stacey Marlise Gahagan and Alfred L. Brophy ISSN 0041-9915 (print) 1942-8405 (online) ● DOI 10.5195/lawreview.2014.342 http://lawreview.law.pitt.edu This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. This site is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D- Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. READING PROFESSOR OBAMA: RACE AND THE AMERICAN CONSTITUTIONAL TRADITION Stacey Marlise Gahagan* and Alfred L. Brophy** ABSTRACT Reading Professor Obama mines Barack Obama’s syllabus on “Current Issues in Racism and the Law” for evidence of his beliefs about race, law, and jurisprudence. The syllabus for the 1994 seminar at the University of Chicago, which provides the reading assignments and structure for the course, has been available on the New York Times website since July 2008. Other than a few responses solicited by the New York Times when it published the syllabus, however, there has been little attention to the material Obama assigned or to what it suggests about Obama’s approach to the law and race. The class began with four weeks of foundational readings followed by four weeks of student-led class discussions. The readings started by discussing the malleability of racial categories and progressed to cases from the nineteenth century on Native Americans and on slavery. The second day’s readings shifted to the Reconstruction era and changes in the Constitution and statutory law, as well as the rise of the “Jim Crow” system of segregation and the response of African American intellectuals. -

10-25-06 DPSC Renzi Complete

STATE OF NEW JERSEY NEW JERSEY DEATH PENALTY STUDY COMMISSION ____________________________________ IN RE: NEW JERSEY DEATH PENALTY STUDY COMMISSION ____________________________________ Office of Legislative Services 225 West State Street, State House Annex Trenton, New Jersey 08625 Wednesday, October 25, 2006 1:05 p.m. to 6:10 p.m. GUY J. RENZI & ASSOCIATES GOLDEN CREST CORPORATE CENTER 2277 State Highway 33, Suite 410 Trenton, New Jersey 08690 609-989-9199 or 800-368-7652 (TOLL FREE) www.renziassociates.com B E F O R E: REVEREND M. WILLIAM HOWARD JR., Chairman GABRIEL R. NEVILLE, Commission Aide JAMES P. ABBOTT JUSTICE JAMES H. COLEMAN JR. EDWARD J. DEFAZIO KATHLEEN M. GARCIA KEVIN HAVERTY EDDIE HICKS THOMAS F. KELAHER BORIS MOCZULA, Attorney General Representative SENATOR JOHN F. RUSSO RABBI ROBERT SCHEINBERG YVONNE SMITH SEGARS MILES S. WINDER III 2 I N D E X PAGE WITNESS TESTIMONY Kent Scheidegger (Via Videoconference) 5 Sam D. Millsap Jr. 15 Charles J. Ogletree (Via Videoconference) 28 James Barbo 55 Gary J. Hilton Sr. 63 William Piper 78 Molly Weigel 78 Celeste Fitzgerald 84 Kathleen M. Hiltner 92 Janet Poinsett 96 David Shepard 103 Bryan Miller 108 Kathryn Schwartz 112 David A. Ruhnke 115 Clare Laura Hogenauer 122 John Nickas 125 Thomas F. Langan 127 3 REVEREND M. WILLIAM HOWARD JR. (CHAIR): Good afternoon, everyone. Good afternoon. I'm Bill Howard, chair of the Committee, and we want to apologize that this room is so small and will not apparently accommodate all who are interested in our public session. But we have indeed arranged for an auxiliary room, and I'd like to ask those who are not speaking if you would consider taking advantage of the arrangements that have been made rather than to stand. -

July 2008 July “ So You Want to Be a Law Professor … ” Page 3

Harvard Law Today july 2008 july “ So you want to be a law professor … ” page 3 New training for future professors HLS adds resources for aspiring academics By Seth Stern ’01 hen pamela foohey ’08 THE GOAL is to make wanted to discuss a potential sure anyone who wants Wcareer as a law professor, she to consider this as a knew just where to turn. job opportunity can She sat down with Akiba Covitz, who, have it as an option.” as director of Harvard Law School’s Office of Academic Affairs, is offering Akiba Covitz advice to students and alumni interested in legal academia. in the number of law professors it has Foohey also is among the first batch produced. But the goal, says Professor JON CHASE/HARVARD NEWS OFFICE NEWS JON CHASE/HARVARD of fellows in a post-graduate research Daryl Levinson, who is heading the OUT WITH A BANG! “You’ve shown that you know program at HLS that gives recent effort, is to make sure there’s more you can use law to make a difference—a positive and an graduates access to the law library and structure in place to help those who online databases they need to pursue want to follow in their footsteps. enduring difference in people’s lives, and that you want to scholarship. Levinson and Covitz have held take the opportunities offered to do so. ... I count on you to It’s all part of the school’s effort to ease information sessions for students and go out and do great deeds in other communities across this the path for students and alumni who alumni—and even created a video nation and around this world.” —Dean Elena Kagan ’86, June want to become law professors.