Parsing the Plagiary Scandals in History and Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“A Flurry of Fascination” the (Anti)Plagiarism Cases of Stephen Ambrose and Doris Kearns Goodwin

1 “A Flurry of Fascination” The (Anti)Plagiarism Cases of Stephen Ambrose and Doris Kearns Goodwin IN THE FIRST week of January 2002, a crime was committed. For some, the crime had actually taken place many months, even years, before the New York Times published the first of many reports on the topic. For others, the offense came later as scattered details coalesced and the several participants (perpetra- tors and victims alike) stated positions for the record. And yet, for many the crime never happened at all, but rather those accused had been falsely charged by an envious, resentful few. In the end, it would not be clear as to who did what, when, where, to whom, and why. Nevertheless, something did happen in early 2002, and the goal of this retelling is to consider how the many players involved managed to articulate both the nature of the crime and its relevance to education, scholarship, and American culture at large. These players would include a handful of state uni- versities, several college professors and students, one major publishing house, a slew of journalists, a few concerned citizens, three spokespersons, a staff of re- search assistants, and a series of experts prepared to wax eloquent on topics ranging from the proper use of punctuation marks to the diabolical repercus- sions of selling one’s soul. The issues at stake would be biggies: integrity, truth, honesty, discipline, courage, tradition. New and old technologies—computers, word-processing software, and the Internet, but also plain old paper, pencil, and handwriting—would factor in as evidence, and even accessories to the crime. -

Academic Freedom” Adria Battaglia

Back to Volume Five Contents Opportunities of Our Own Making: The Struggle for “Academic Freedom” Adria Battaglia Abstract This essay examines David Horowitz’s “Academic Freedom” campaign, specifically exploring how “academic freedom,” a narrative that appears alongside “free speech” discourse frequently since September 11, 2001, can be understood as a site of struggle, a privileged label that grants legitimacy to those controlling it. This analysis includes public debates, interviews, and blog postings spanning the 2003 launch of Horowitz’s campaign, discussions of the proposed legislation in 2007, and his publication in 2009 of One-Party Classroom. By exposing the various ways Horowitz’s campaign is framed in the media by interested parties, I demonstrate how the link between “academic freedom” and “free speech” becomes a rhetorical strategy by which we can gain political and economic legitimacy. A recent Harvard study indicates that many young people have yet to become involved in politics not because they are uninterested, but because they have yet to be given the opportunity. —“The 15th Biannual Youth Survey on Politics and Public Service,” Institute of Politics at Harvard University, 2008 On March 4, 2010, young people were given an opportunity. After months of organizing, “hundreds of thousands took part in what was the largest day of coordinated student protest in years.” 1 College and university campuses across the United States became sites of marches, strikes, teach-ins, and walkouts. The “Day of Action” was organized by the California Coordinating Committee in the hopes of AAUP Journal of Academic Freedom 2 Volume Five becoming “an historic turning point in the struggle against the cuts, layoffs, fee hikes, and the re-segregation of public education.”2 Democracy Now! host Amy Goodman describes the scenes across the nation: At the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, police used pepper spray to break up a student protest organized by Students for a Democratic Society. -

House of Lords Official Report

Vol. 739 Tuesday No. 44 9 October 2012 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) HOUSE OF LORDS OFFICIAL REPORT ORDER OF BUSINESS Questions House of Lords: Appointments Parliamentary Constituency Boundaries: Review Olympic and Paralympic Games 2012 Railways: Franchises Economic Affairs Committee Membership Motion Justice and Security Bill [HL] Order of Consideration Motion Defamation Bill Second Reading Britain’s Industrial Base Question for Short Debate Grand Committee Education: Further Education Colleges Question for Short Debate UK Trade and Investment Question for Short Debate Health: Cancer Question for Short Debate Bangladesh: Human Rights Question for Short Debate Written Statements Written Answers For column numbers see back page £3·50 Lords wishing to be supplied with these Daily Reports should give notice to this effect to the Printed Paper Office. The bound volumes also will be sent to those Peers who similarly notify their wish to receive them. No proofs of Daily Reports are provided. Corrections for the bound volume which Lords wish to suggest to the report of their speeches should be clearly indicated in a copy of the Daily Report, which, with the column numbers concerned shown on the front cover, should be sent to the Editor of Debates, House of Lords, within 14 days of the date of the Daily Report. This issue of the Official Report is also available on the Internet at www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201213/ldhansrd/index/121009.html PRICES AND SUBSCRIPTION RATES DAILY PARTS Single copies: Commons, £5; Lords £3·50 Annual subscriptions: Commons, £865; Lords £525 WEEKLY HANSARD Single copies: Commons, £12; Lords £6 Annual subscriptions: Commons, £440; Lords £255 Index: Annual subscriptions: Commons, £125; Lords, £65. -

They Hate US for Our War Crimes: an Argument for US Ratification of the Rome Statute in Light of the Post-Human Rights

UIC Law Review Volume 52 Issue 4 Article 4 2019 They Hate U.S. for Our War Crimes: An Argument for U.S. Ratification of the Rome Statute in Light of the ost-HumanP Rights Era, 53 UIC J. MARSHALL. L. REV. 1011 (2019) Michael Drake Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, International Humanitarian Law Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Michael Drake, They Hate U.S. for Our War Crimes: An Argument for U.S. Ratification of the Rome Statute in Light of the Post-Human Rights Era, 53 UIC J. MARSHALL. L. REV. 1011 (2019) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol52/iss4/4 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THEY HATE U.S. FOR OUR WAR CRIMES: AN ARGUMENT FOR U.S. RATIFICATION OF THE ROME STATUTE IN LIGHT OF THE POST-HUMAN RIGHTS ERA MICHAEL DRAKE* I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................... 1012 II. BACKGROUND ............................................................ 1014 A. Continental Disparities ......................................... 1014 1. The International Process in Africa ............... 1014 2. The National Process in the United States of America ............................................................ 1016 B. The Rome Statute, the ICC, and the United States ................................................................................. 1020 1. An International Court to Hold National Leaders Accountable ...................................................... 1020 2. The Aims and Objectives of the Rome Statute .......................................................................... 1021 3. African Bias and U.S. -

The Political Economy of Colorblindness: Neoliberalism and the Reproduction of Racial Inequality in the United States

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF COLORBLINDNESS: NEOLIBERALISM AND THE REPRODUCTION OF RACIAL INEQUALITY IN THE UNITED STATES A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University By Phillip A. Hutchison Master of Arts University of California, Los Angeles, 2002 Director: Paul Smith, Professor Cultural Studies Fall Semester 2010 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright: 2010 Phillip A. Hutchison All Rights Reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract ............................................................................................................................. iv Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 Literature Review............................................................................................................. 30 Chapter 1 .......................................................................................................................... 69 Chapter 2 .......................................................................................................................... 94 Chapter 3 ........................................................................................................................ 138 Chapter 4 ........................................................................................................................ 169 Chapter 5 ....................................................................................................................... -

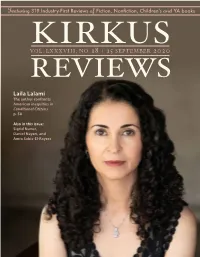

Kirkus Reviews on Our Website by Logging in As a Subscriber

Featuring 319 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books VOL.KIRKUS LXXXVIII, NO. 18 | 15 SEPTEMBER 2020 REVIEWS Laila Lalami The author confronts American inequities in Conditional Citizens p. 58 Also in this issue: Sigrid Nunez, Daniel Nayeri, and Amra Sabic-El-Rayess from the editor’s desk: The Way I Read Now Chairman BY TOM BEER HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # Among the many changes in my daily life this year—working from home, Chief Executive Officer wearing a mask in public, watching too much TV—my changing read- MEG LABORDE KUEHN ing habits register deeply. For one thing, I read on a Kindle now, with the [email protected] Editor-in-Chief exception of the rare galley sent to me at home and the books I’ve made TOM BEER a point of purchasing from local independent bookstores or ordering on [email protected] Vice President of Marketing Bookshop.org. The Kindle was borrowed—OK, confiscated—from my SARAH KALINA boyfriend at the beginning of the pandemic, when I left dozens of advance [email protected] reader copies behind at the office and accepted the reality that digital gal- Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU leys would be a practical necessity for the foreseeable future. I can’t say that I [email protected] love reading on my “new” Kindle—I’m still a sucker for physical books after Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK all these years—but I’ll admit that it fulfills its purpose efficiently. And I do [email protected] Tom Beer rather enjoy the instant gratification of going on NetGalley or Edelweiss Young Readers’ Editor VICKY SMITH and dispatching multiple books to my device in one fell swoop—a harmless [email protected] form of bingeing that affords a little dopamine rush. -

Righting the Wrongs of Slavery, 89 Geo. LJ 2531

UIC School of Law UIC Law Open Access Repository UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2001 Forgive U.S. Our Debts? Righting the Wrongs of Slavery, 89 Geo. L.J. 2531 (2001) Kevin Hopkins John Marshall Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs Part of the Law and Race Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Kevin Hopkins, Forgive U.S. Our Debts? Righting the Wrongs of Slavery, 89 Geo. L.J. 2531 (2001). https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs/153 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVIEW ESSAY Forgive U.S. Our Debts? Righting the Wrongs of Slavery KEvIN HOPKINS* "We must make sure that their deaths have posthumous meaning. We must make sure that from now until the end of days all humankind stares this evil in the face.., and only then can we be sure it will never arise again." President Ronald Reagan' INTRODUCTION: Tm BIG PAYBACK In recent months, claims for reparations for slavery have gained new popular- ity amongst black intellectuals and trial lawyers and have been given additional momentum by the publication of Randall Robinson's controversial and thought- provoking book, The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks.2 In The Debt, Robinson makes a serious and persuasive case for the payment of reparations by the United States government to African-Americans for both the injustices done to their ancestors during slavery and the effect of those wrongs on the current * Associate Professor of Law, The John Marshall Law School. -

THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS and HISTORICAL CONTEXT the Study of Emigration of Jews from Arab Countries to Israel Has Largely Been

CHAPTER ONE THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS AND HISTORICAL CONTEXT The study of emigration of Jews from Arab countries to Israel has largely been motivated by sectarianism and political partisanship. Authors with Zionist inclinations tend to see this emigration as the result of Muslim persecution of Jews, while at the same time viewing the process of aliyah to Israel as a redemption. According to this narrative, Jews in Arab coun- tries lived in an almost constant state of longing for Zion. Messianic impulses, coupled with constant persecution, drove Jews to immigrate to Israel as soon as they had the opportunity to do so.1 Recently, this narrative has been appropriated by those wishing to attribute refugee status to Jews from Arab countries. Several organizations have been formed to advocate for restitutions for those Jews, individually or as communities, who left or lost property and assets in Arab countries.2 One author, Yaʿakov Meron, goes as far as to call this emigration an expul- sion, yet as he points out regarding Yemen: “A bribe from the American Joint Distribution Committee to Yemen’s ruler, Imam Ahmed ibn Yahya, led to his agreeing to the mass exodus of Jews to Israel in 1949–1950…”3 1 On messianism see Eraqi-Klorman, Jews of Yemen in the Nineteenth Century, 90–119; Ahroni, Yemenite Jewry; Parfitt, Road to Redemption. On persecution see Bat Yeor, The Dhimmi: Jews and Christians under Islam (Rutherford; London: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press; Associated University Presses, 1985); Devorah Hakohen and Menahem Hakohen, One People: The Story of the Eastern Jews (New York: Adama Books, 1986); Joan Peters, From Time Immemorial: The Origins of the Arab-Jewish Conflict over Palestine (New York: Harper & Row, 1984); Tawil, Operation Esther. -

Selected Bibliography of Work About and of Edward Said's Texts

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 5 (2003) Issue 4 Article 7 Selected Bibliography of Work about and of Edward Said's Texts Clare Callaghan University of Maryland Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Callaghan, Clare. "Selected Bibliography of Work about and of Edward Said's Texts." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 5.4 (2003): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1203> The above text, published by Purdue University Press ©Purdue University, has been downloaded 13859 times as of 11/07/19. -

Ford Hall Forum Collection (MS113), 1908-2013: a Finding Aid

Ford Hall Forum Collection 1908-2013 (MS113) Finding Aid Moakley Archive and Institute www.suffolk.edu/moakley [email protected] Ford Hall Forum Collection (MS113), 1908-2013: A Finding Aid Descriptive Summary Repository: Moakley Archive and Institute, Suffolk University, Boston MA Collection Number: MS 113 Creator: Ford Hall Forum Title: Ford Hall Forum Collection Date(s): 1908-2013, 1930-2000 Quantity: 85 boxes, 41 cubic ft., 39 lin. ft. Preferred Citation: Ford Hall Forum Collection (MS 113), 1908-2013, Moakley Archive and Institute, Suffolk University, Boston, MA. Abstract: The Ford Hall Forum Collection documents the history of the nation’s longest running free public lecture series. The Forum has hosted some the most notable figures in the arts, science, politics, and the humanities since its founding in 1908. The collection, which spans from 1908 to 2013, includes of 85 boxes of materials related to the Forum's administration, lectures, fund raising, partnerships, and its radio program, the New American Gazette. Administrative Information Acquisition Information: Ownership transferred to Suffolk University in 2014. Use Restrictions: Use of materials may be restricted based on their condition, content or copyright status, or if they contain personal information. Consult Archive staff for more information. Related Collections: See also the Ford Hall Forum Oral History (SOH-041) and Arthur S. Meyers Collection (MS114) held by Suffolk University. Additional collection materials related to the organization --primarily audio and video -

![Download Music for Free.] in Work, Even Though It Gains Access to It](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0418/download-music-for-free-in-work-even-though-it-gains-access-to-it-680418.webp)

Download Music for Free.] in Work, Even Though It Gains Access to It

Vol. 54 No. 3 NIEMAN REPORTS Fall 2000 THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY 4 Narrative Journalism 5 Narrative Journalism Comes of Age BY MARK KRAMER 9 Exploring Relationships Across Racial Lines BY GERALD BOYD 11 The False Dichotomy and Narrative Journalism BY ROY PETER CLARK 13 The Verdict Is in the 112th Paragraph BY THOMAS FRENCH 16 ‘Just Write What Happened.’ BY WILLIAM F. WOO 18 The State of Narrative Nonfiction Writing ROBERT VARE 20 Talking About Narrative Journalism A PANEL OF JOURNALISTS 23 ‘Narrative Writing Looked Easy.’ BY RICHARD READ 25 Narrative Journalism Goes Multimedia BY MARK BOWDEN 29 Weaving Storytelling Into Breaking News BY RICK BRAGG 31 The Perils of Lunch With Sharon Stone BY ANTHONY DECURTIS 33 Lulling Viewers Into a State of Complicity BY TED KOPPEL 34 Sticky Storytelling BY ROBERT KRULWICH 35 Has the Camera’s Eye Replaced the Writer’s Descriptive Hand? MICHAEL KELLY 37 Narrative Storytelling in a Drive-By Medium BY CAROLYN MUNGO 39 Combining Narrative With Analysis BY LAURA SESSIONS STEPP 42 Literary Nonfiction Constructs a Narrative Foundation BY MADELEINE BLAIS 43 Me and the System: The Personal Essay and Health Policy BY FITZHUGH MULLAN 45 Photojournalism 46 Photographs BY JAMES NACHTWEY 48 The Unbearable Weight of Witness BY MICHELE MCDONALD 49 Photographers Can’t Hide Behind Their Cameras BY STEVE NORTHUP 51 Do Images of War Need Justification? BY PHILIP CAPUTO Cover photo: A Muslim man begs for his life as he is taken prisoner by Arkan’s Tigers during the first battle for Bosnia in March 1992. -

From a Native

From a Native Son Selected Essays in Indigenism, 1985–1995, Second Edition Ward Churchill • Introduction by Howard Zinn From a Native Son was the first volume of acclaimed American Indian Movement activist-intellectual Ward Churchill’s essays in indigenism, selected from material written during the decade 1985–1995. Presented here in a new revised edition that includes four additional pieces, three of them previously unpublished, the book illuminates Churchill’s early development of the themes with which he has, in the words of Noam Chomsky, “carved out a special place for himself in de- fending the rights of oppressed people, and exposing the dark side of past and current history, often forgotten, marginalized, or suppressed.” Topics addressed include the European conquest and colonization of the Americas, including the genocidal record of Christopher Columbus, the sys- tematic “clearing” and resettlement of American Indian territories by the United States and its antecedents, academic subterfuges designed to deny or disguise the extent of Indian land rights, radioactive contamination of Indian reservations by energy corporations, government-sponsored death squads used to “neutral- ize” the native struggle on the Pine Ridge Reservation during the mid-1970s, the ongoing dehumanization of American Indians in literature, cinema, and by SUBJECT CATEGORY their portrayal as sports team mascots, issues of Indian identity and the expro- History-U.S./Native American Studies priation of indigenous spiritual traditions, the negative effects of “postmodern- ism” upon understandings of contemporary circumstances of native people, PRICE the false promise of marxism in terms of indigenous liberation, and what, from $24.95 an indigenist standpoint, the genuine decolonization of North America might look like.