Film Adaptation, Alternative Cinema And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Caglione, Jr

JOHN CAGLIONE, JR. Make-Up Designer IATSE 798 and 706 FILM BROKEN CITY Personal Make-Up Artist to Russell Crowe Director: Allen Hughes PHIL SPECTOR Personal Make-Up Artist to Al Pacino Director: David Mamet TOWER HEIST Department Head Director: Brett Ratner ON THE ROAD Special Make-Up Effects Director: Walter Salles Cast: Viggo Mortensen THE SMURFS Department Head Director: Raja Gosnell YOU DON’T KNOW JACK Personal Make-Up Artist to Al Pacino Director: Barry Levinson Nominee: Emmy Award for Outstanding Make-Up for a Miniseries or Movie SALT Department Head Director: Philip Noyce STATE OF PLAY Personal Make-Up Artist to Russell Crowe Director: Kevin Macdonald THE DARK KNIGHT Personal Make-Up Artist to Heath Ledger Director: Christopher Nolan Nominee: Academy Award for Best Achievement in Make-Up Nominee: Saturn Award for Best Make-Up 3:10 TO YUMA Personal Make-Up Artist to Russell Crowe Director: James Mangold AMERICAN GANGSTER Personal Make-Up Artist to Russell Crowe Director: Ridley Scott THE DEPARTED Department Head Make-Up and Department Head Effects Make-Up Director: Martin Scorsese Cast: Vera Farmiga, Ray Winstone, Kristen Dalton TENDERNESS Department Head Director: John Polson Cast: Russell Crowe, Laura Dern, Jon Foster, Tonya Clarke THE MILTON AGENCY John Caglione, Jr. 6715 Hollywood Blvd #206, Los Angeles, CA 90028 Make-Up Telephone: 323.466.4441 Facsimile: 323.460.4442 IATSE 798 & 706 [email protected] www.miltonagency.com Page 1 of 4 MY SUPER EX-GIRLFRIEND Department Head Director: Ivan Reitman Cast: Luke Wilson, Anna -

80S 90S Hand-Out

FILM 160 NOIR’S LEGACY 70s REVIVAL Hickey and Boggs (Robert Culp, 1972) The Long Goodbye (Robert Altman, 1973) Chinatown (Roman Polanski, 1974) Night Moves (Arthur Penn, 1975) Farewell My Lovely (Dick Richards, 1975) The Drowning Pool (Stuart Rosenberg, 1975) The Big Sleep (Michael Winner, 1978) RE- MAKES Remake Original Body Heat (Lawrence Kasdan, 1981) Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944) Postman Always Rings Twice (Bob Rafelson, 1981) Postman Always Rings Twice (Garnett, 1946) Breathless (Jim McBride, 1983) Breathless (Jean-Luc Godard, 1959) Against All Odds (Taylor Hackford, 1984) Out of the Past (Jacques Tourneur, 1947) The Morning After (Sidney Lumet, 1986) The Blue Gardenia (Fritz Lang, 1953) No Way Out (Roger Donaldson, 1987) The Big Clock (John Farrow, 1948) DOA (Morton & Jankel, 1988) DOA (Rudolf Maté, 1949) Narrow Margin (Peter Hyams, 1988) Narrow Margin (Richard Fleischer, 1951) Cape Fear (Martin Scorsese, 1991) Cape Fear (J. Lee Thompson, 1962) Night and the City (Irwin Winkler, 1992) Night and the City (Jules Dassin, 1950) Kiss of Death (Barbet Schroeder 1995) Kiss of Death (Henry Hathaway, 1947) The Underneath (Steven Soderbergh, 1995) Criss Cross (Robert Siodmak, 1949) The Limey (Steven Soderbergh, 1999) Point Blank (John Boorman, 1967) The Deep End (McGehee & Siegel, 2001) Reckless Moment (Max Ophuls, 1946) The Good Thief (Neil Jordan, 2001) Bob le flambeur (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1955) NEO - NOIRS Blood Simple (Coen Brothers, 1984) LA Confidential (Curtis Hanson, 1997) Blue Velvet (David Lynch, 1986) Lost Highway (David -

The Dark Past Keeps Returning: Gender Themes in Neo-Noir by Heather Fireman

The Dark Past Keeps Returning: Gender Themes in Neo-Noir by Heather Fireman "Films are full of good things which really ought to be invented all over again. Again and again. Invented - not repeated. The good things should be found - found - in that precious spirit of the first time out, and images discovered - not referred to.... Sure, everything's been done.... Hell, everything had all been done when I started" -Orson Welles (Naremore 219). Film noir, an enigmatic and compelling mode, can and has been resurrected in many movies in recent years. So-called "neo-noirs" evoke the look, style, mood, or even just the feel of classic noir. Having sprung from a particular moment in history and resonating with the mentality of its audiences, noir should also be considered in terms of a context, which was vital to its ability to create meaning for its original audiences. We can never know exactly how those audiences viewed the noirs of the 1940s and 50s, but modern audiences obviously view them differently, in contexts "far removed from the ones for which they were originally intended" (Naremore 261). These films externalized fears and anxieties of American society of the time, generating a dark feeling or mood to accompany its visual style. But is a noir "feeling" historically bound? What does this mean for neo-noirs? Contemporary America has distinctive features that set it apart from the past. Even though neo-noir films may borrow generic conventions of classic noir, the "language" of noir is used to express anxieties belonging to modern times. -

Portraits of America DEMOCRACY on FILM

The Film Foundation’s Story of Movies Presents With support from AFSCME A PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT WORKSHOP ON FILM AND VISUAL LITERACY FOR CLASSROOM EDUCATORS ACROSS ALL DISCIPLINES, GRADES 5 – 12 Portraits of America DEMOCRACY ON FILM 2018 WORKSHOPS August 6 & 7 Breen Center for the Performing Arts, 2008 W 30th Street, Cleveland, OH 44113 August 14 & 15 Lightbox Film Center inside International House Philadelphia 3701 Chestnut Street Philadelphia, PA 19104 October 3 & 4 Detroit Institute of Arts, 5200 Woodward Ave., Detroit, MI 48202 WHO & WHAT This FREE two-day seminar introduces educators to an interdisciplinary curriculum that challenges students to think contextually about the role of film as an expression of American democracy. SCREENING AND DISCUSSION ACTIVITIES FOCUS ON STRATEGIES TO: N Increase civic engagement by developing students’ critical viewing and thinking skills. N Give students the tools to understand the persuasive and universal language of moving images, a significant component ofvisual literacy. N Explore the social issues and diverse points of view represented in films produced in different historical periods. MORNING AND AFTERNOON WORKSHOPS FOCUS ON LEARNING HOW TO READ A FILM, PRINCIPLES OF CINEMA LITERACY, AND INTERPRETING FILM IN HISTORICAL/CULTURAL CONTEXTS. N Handout materials include screening activities and primary source documents to support and enhance students’ critical thinking skills. N Evening screenings showcase award-winning films, deemed historically and culturally significant by the Library of Congress National Film Registry. N Lunch is provided for registered participants. HOW & WHEN TO REGISTER CLASSROOM CAPACITY IS LIMITED, SO EARLY REGISTRATION IS ENCOURAGED. Continuing Education Credits may be supported by local school districts for this program. -

Film As Philosophy in Memento: Reforming Wartenberg's Imposition

!"#$%&'%()"#*'*+),%"-%!"#"$%&.% /01*2$"-3%4&250-60237'%8$+*'"5"*-%96:0;5"*- "#$%&#$'%()*+%*%,'-*,'%!"#$%&'(%)*"#+,+-*.%*+,%()'%/+01'&#%+2%34,5*45"6,% &'(%315%71"5"6",$%)*.'%/01234)',%*%$0++3+5%,'1*('%*4%(#%6)'()'$%-#&&'$-3*2% +*$$*(3.'%73-(3#+%732&4!%*$'%-*/*12'%#7%(+"'8%/)32#4#/)89%/'$)*/4%'.'+%#$353+*2% /)32#4#/)89%3+%()'3$%#6+%$35)(:%%;)34%,'1*('%1'5*+%63()%()'%*//'*$*+-'9%3+%<===9%#7% >$0-'%?044'22@4%A0*2373',28%+'5*(3.'%.'$,3-(%#+%()34%A0'4(3#+9%B;)'%C)32#4#/)3-*2% D3&3(4%#7%"32&9E<%*+,%F('/)'+%G02)*22@4%.'$8%3+720'+(3*2%/#43(3.'%.'$,3-(%*%8'*$% 2*('$9%3+%9'%!"#$:H%%F3+-'%()'+%+0&'$#04%*$(3-2'4%)*.'%1''+%,'.#(',%(#%()'%3440'9% 3+-20,3+5%()'%'+(3$'%I3+('$9%<==J%3440'%#7%:*4%/+01'&#%+2%34,5*45"6,%&'(%315% 71"5"6",$9K%*+,%*%4'(%#7%7#0$%*$(3-2'4%*//'*$3+5%3+%!"#$%&'(%)*"#+,+-*.%(6#%8'*$4% 2*('$:L%%"#0$%&#$'%1##M%2'+5()%($'*(&'+(4%#7%()'%(#/3-%)*.'%*24#%'&'$5',%()04%7*$N% O*+3'2%"$*&/(#+@4%!"#$+,+-*.%3+%<==J9J%;#&%I*$('+1'$5@4%:*"';"'8%+'%<6144'=% !"#$%&,%)*"#+,+-*.%3+%<==P9P%*%4'-#+,%',3(3#+9%5$'*(28%'Q/*+,',9%#7%G02)*22@4%9'% !"#$%3+%<==R9R%*+,%C*342'8%D3.3+54(#+@4%7"'4$&>%)*"#+,+-*.>%?418$&'=%9'%!"#$% &,%)*"#+,+-*.9%3+%<==S:S% T+'%3&/#$(*+(%-#+4($*3+(%#+%732&4%A0*23783+5%*4%403(*128%-*"#+,+-*"6&#%)*4% 1''+%F('/)'+%G02)*22@4%5$#0+,%$02'9%7$*&',%'*$28%3+%()'%,'1*('N%732&4%,#%+#(% -#0+(%*4%,#3+5%/)32#4#/)8%3+%()'3$%#6+%$35)(%37%()'8%&'$'28%2'+,%()'&4'2.'4%(#% /)32#4#/)3-*2%3+('$/$'(*(3#+%()$#05)%4@541'&#%*//23-*(3#+%#7%()'#$3'4:%%BF/'-373-% ()'#$'(3-*2%',373-'4%U#$353+*(3+5%'24'6)'$'9%3+%40-)%,#&*3+4%*4%/48-)#*+*28434% #$%/#23(3-*2%()'#$8V9E%4#&'(3&'4%($'*(%()'%(*$5'(%732&%B#+28%*4%*%-02(0$*2%/$#,0-(% -

The End of Japanese Cinema

THE END OF JAPANESE CINEMA TIMES ALEXANDER ZAHLTEN THE END OF JAPA NESE CINEMA studies of the weatherhead east asian institute, columbia university. The Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute of Columbia University w ere inaugurated in 1962 to bring to a wider public the results of significant new research on modern and con temporary East Asia. alexander zahlten THE END OF JAPA NESE CINEMA Industrial Genres, National Times, and Media Ecologies Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2017 © 2017 DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Text designed by Courtney Leigh Baker Typeset in Arno Pro and Din by Westchester Publishing Ser vices Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Zahlten, Alexander, [date] author. Title: The end of Japa nese cinema : industrial genres, national times, and media ecologies / Alexander Zahlten. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Series: Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version rec ord and cip data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn 2017012588 (print) lccn 2017015688 (ebook) isbn 9780822372462 (ebook) isbn 9780822369295 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822369448 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Motion pictures— Japan— History—20th century. | Mass media— Japan— History—20th century. Classification: lcc pn1993.5.j3 (ebook) | lcc pn1993.5.j3 Z34 2017 (print) -

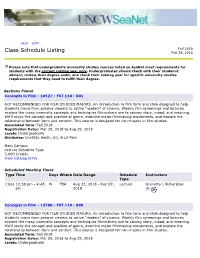

Class Schedule Listing Mar 28, 2018

HELP | EXIT Fall 2018 Class Schedule Listing Mar 28, 2018 Please note that undergraduate university studies courses listed on SeaNet meet requirements for students with the current catalog year only. Undergraduates should check with their academic advisor, review their degree audit, and check their catalog year for specific university studies requirements that they need to fulfill their degree. Sections Found Concepts in Film - 10527 - FST 110 - 001 NOT RECOMMENDED FOR FILM STUDIES MAJORS. An introduction to film form and style designed to help students move from passive viewers to active “readers” of cinema. Weekly film screenings and lectures explore the many cinematic concepts and techniques filmmakers use to convey story, mood, and meaning. We’ll study the concept and practice of genre, examine major filmmaking movements, and explore the relationship between form and content. This course is designed for non-majors in film studies. Associated Term: Fall 2018 Registration Dates: Mar 29, 2018 to Aug 29, 2018 Levels: Undergraduate Attributes: UnvStdy Aesth, Int, & Lit Pers Main Campus Lecture Schedule Type 3.000 Credits View Catalog Entry Scheduled Meeting Times Type Time Days Where Date Range Schedule Instructors Type Class 12:30 pm - 4:45 W TBA Aug 22, 2018 - Dec 07, Lecture Granetta L Richardson pm 2018 (P) Concepts in Film - 12780 - FST 110 - 800 NOT RECOMMENDED FOR FILM STUDIES MAJORS. An introduction to film form and style designed to help students move from passive viewers to active “readers” of cinema. Weekly film screenings and lectures explore the many cinematic concepts and techniques filmmakers use to convey story, mood, and meaning. -

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS BEST FIRST SCREENPLAY 2012 NOMINEES (Winners in bold) *Will Reiser 50/50 BEST FEATURE (Award given to the producer(s)) Mike Cahill & Brit Marling Another Earth *The Artist Thomas Langmann J.C. Chandor Margin Call 50/50 Evan Goldberg, Ben Karlin, Seth Rogen Patrick DeWitt Terri Beginners Miranda de Pencier, Lars Knudsen, Phil Johnston Cedar Rapids Leslie Urdang, Dean Vanech, Jay Van Hoy Drive Michel Litvak, John Palermo, BEST FEMALE LEAD Marc Platt, Gigi Pritzker, Adam Siegel *Michelle Williams My Week with Marilyn Take Shelter Tyler Davidson, Sophia Lin Lauren Ambrose Think of Me The Descendants Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor Rachael Harris Natural Selection Adepero Oduye Pariah BEST FIRST FEATURE (Award given to the director and producer) Elizabeth Olsen Martha Marcy May Marlene *Margin Call Director: J.C. Chandor Producers: Robert Ogden Barnum, BEST MALE LEAD Michael Benaroya, Neal Dodson, Joe Jenckes, Corey Moosa, Zachary Quinto *Jean Dujardin The Artist Another Earth Director: Mike Cahill Demián Bichir A Better Life Producers: Mike Cahill, Hunter Gray, Brit Marling, Ryan Gosling Drive Nicholas Shumaker Woody Harrelson Rampart In The Family Director: Patrick Wang Michael Shannon Take Shelter Producers: Robert Tonino, Andrew van den Houten, Patrick Wang BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE Martha Marcy May Marlene Director: Sean Durkin Producers: Antonio Campos, Patrick Cunningham, *Shailene Woodley The Descendants Chris Maybach, Josh Mond Jessica Chastain Take Shelter -

Hartnett Dissertation

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Recorded Objects: Time-Based Technologically Reproducible Art, 1954-1964 A Dissertation Presented by Gerald Hartnett to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University August 2017 Stony Brook University 2017 Copyright by Gerald Hartnett 2017 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Gerald Hartnett We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Andrew V. Uroskie – Dissertation Advisor Associate Professor, Department of Art Jacob Gaboury – Chairperson of Defense Assistant Professor, Department of Art Brooke Belisle – Third Reader Assistant Professor, Department of Art Noam M. Elcott, Outside Reader Associate Professor, Department of Art History, Columbia University This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Charles Taber Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Recorded Objects: Time-Based, Technologically Reproducible Art, 1954-1964 by Gerald Hartnett Doctor of Philosophy in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University 2017 Illuminating experimental, time-based, and technologically reproducible art objects produced between 1954 and 1964 to represent “the real,” this dissertation considers theories of mediation, ascertains vectors of influence between art and the cybernetic and computational sciences, and argues that the key practitioners responded to technological reproducibility in three ways. First of all, writers Guy Debord and William Burroughs reinvented appropriation art practice as a means of critiquing retrograde mass media entertainments and reportage. -

HILBERT HAKIM Second Assistant Director DGA

HILBERT HAKIM Second Assistant Director DGA FILM THE FATE OF THE FURIOUS (AKA The Key Second Assistant Director Fast and the Furious 8) Director: F. Gary Gray Producers: Neal Moritz, Vin Diesel, Michael Fottrell UPM: Carla Raij First Assistant Director: Cliff Lanning FRESH OFF THE BOAT Key Second Assistant Director 20th Century Fox Television/ABC Director: Various Producer: Jake Kasdan First Assistant Director: Carey Dietrich, Sean Kavanagh Unit Production Manager: Barbara Black TAMMY Key Second Assistant Director (Re-Shoots) New Line Cinema Director: Ben Falcone Producers: Will Farrel, Rob Cowan, Melissa McCarthy First Assistant Director: Michael Amundson Unit Production Manager: Brian Frankish INTO THE SKY Key Second Assistant Director (Re-Shoots) New Line Cinema Director: Steve Quale Producers: Rob Cowan First Assistant Director: Michael Amundson Unit Production Manager: Brian Frankish GULLIVER’S TRAVELS Key Second Assistant Director 20th Century Fox Director: Rob Letterman Producers: John Davis, Gregory Goodman First Assistant Director: Cliff Lanning Unit Production Manager: Janine Modder THE REAPING Second Assistant Director Warner Brothers Director: Stephen Hopkins Producers: Joel Silver, Robert Zemeckis First Assistant Director: Cliff Lanning Line Producer/Unit Production Manager: Herb Gains BATMAN BEGINS Key Second Assistant Director (Chicago) Warner Brothers Director: Christopher Nolan Producers: Emma Thomas, Larry Franco, Chuck Roven First Assistant Director: Clifford Lanning Unit Production Manger: Mike Malone THE MILTON AGENCY -

Caglione, John

John Caglione Jr. MAKE-UP ARTIST SPECIAL MAKE-UP FX DESIGNER IATSE 798 & 706 http://www.johncaglionejr.net FILM (Partial Credits): Teenage Mutant Ninja Department Head – Paramount Pictures Turtles 2 Dir: Dave Green – UPM: Basil Grillo Cast: Will Arnett, Alessandra Ambrosio, Stephen Arnell Fathers & Daughters Department Head – Voltage Pictures Dir: Gabriele Muccino – LP: Richard Middleton Cast: Amanda Seyfried, Russell Crowe, Diane Kruger, Jane Fonda, Octavia Spencer Aloha Department Head – Columbia Pictures Dept Head / Personal Dir: Cameron Croew – UPM: Robert Huberman Cast: Emma Stone, Rachel McAdams, Alec Baldwin, Danny McBride Amazing Spiderman 2 Department Head – Columbia Pictures Dir: Marc Webb – LP: Bennett Walsh Cast: Andrew Garfield, Emma Stone, Denis Leary, Paul Giamatti, Martin Sheen Winter’s Tale Department Head –Warner Bros. Dir: Akiva Goldsman – LP: Mike Tadross Cast: Colin Farrell, Russell Crowe, Matt Bomer, Kevin Durand, William Hurt Paranoia Department Head – Relativity Media Dir: Robert Luketic – LP: William Beasley Cast: Amber Heard, Liam Hemsworth, Gary Oldman, Embeth Davitz, Julian McMahon Broken City Personal Makeup for Russell Crowe – Fox Dir: Allen Hughes - LP: William Beasley Untitled Phil Spector Personal Makeup for Al Pacino – HBO Films Biopic Dir: David Mamet - LP: Michael Hausman Tower Heist Department Head – Universal Pictures Dir: Brett Ratner – LP: Bill Carraro Cast: Eddie Murphy, Casey Affleck, Tea Leoni, Gabourey Sidibe, Matthew Broderick On The Road Special FX Makeup Designer – MK2 Productions Dir: Walter -

TIM ANGULO Director of Photography IATSE Local 600

TIM ANGULO Director of Photography www.timangulo.com IATSE Local 600 A love of movies and an appreciation of the arts led Tim Angulo to a career in cinematography. After graduating from Brooks Institute of Photography and a fellowship at the American Film Institute, Tim began his career as a visual effects/second unit DP. His work has been featured in franchise movies such as Batman, Spiderman and others. He has lensed over 200 commercials and promos and has worked on several high profile 3D projects. Tim is a member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, Visual Effects Society and ICG 600. He has extensive experience in live action, VFX photography, high speed, miniatures and motion control. Features, VFX & Second Unit DP (partial list): Production Director / Production Company FIRST MAN (Visual effects DP/Miniatures) Damien Chazelle / Temple Hill / Universal Academy Award Winner – Best Visual Effects INTERSTELLER (Visual effects DP) Christopher Nolan / Warner Bros. Academy Award Winner – Best Visual Effects INCEPTION (Miniatures) Christopher Nolan / Warner Bros. th NIGHT AT THE MUSEUM 2 (Miniatures & VFX) Shawn Levy / 20 Century Fox TERMINATOR: SALVATION McG / Columbia Pictures THE WATCHMEN (Miniatures & VFX) Zack Snyder / Warner Bros. THE DARK KNIGHT (Miniatures) Christopher Nolan / Warner Bros. RESIDENT EVIL: EXTINCTION (Miniatures/reshoot) Russell Mulcahy / Screen Gems SPIDERMAN 3 Sam Raimi / Columbia Pictures th DECK THE HALLS John Whitesell / 20 Century Fox CHRONICLES OF NARNIA Andrew Adamson / Walden Media / Disney TEAM AMERICA Trey Parker / Paramount Pictures SPIDERMAN 2 Sam Raimi / Columbia Pictures th THE LEAGUE OF EXTRAORDINARY GENTLEMEN Stephen Norrington / 20 Century Fox CHRONICLES OF RIDDICK David Twohy / Universal Pictures THE CAT IN THE HAT Bo Welch / Alphaville Films / Universal GODS & GENERALS Ronald Maxwell / Turner Pictures / Warner Bros SPIDERMAN Sam Raimi / Columbia Pictures SCOOBY DOO Raja Gosnell / Atlas Ent / Warner Bros.