Rapid Response Mechanism in South Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Sudan: Jonglei – “We Have Always Been at War”

South Sudan: Jonglei – “We Have Always Been at War” Africa Report N°221 | 22 December 2014 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Jonglei’s Conflicts Before the Civil War ........................................................................... 3 A. Perpetual Armed Rebellion ....................................................................................... 3 B. The Politics of Inter-Communal Conflict .................................................................. 4 1. The communal is political .................................................................................... 4 2. Mixed messages: Government response to intercommunal violence ................. 7 3. Ethnically-targeted civilian disarmament ........................................................... 8 C. Region over Ethnicity? Shifting Alliances between the Bahr el Ghazal Dinka, Greater Bor Dinka and Nuer ...................................................................................... 9 III. South Sudan’s Civil War in Jonglei .................................................................................. 12 A. Armed Factions in Jonglei ........................................................................................ -

Conflict Trends, Issue 1 (2012)

IS S U E 1 , 2 0 1 2 20 YEARS OF CONTRIBUTING TO PEACE ct1|2012 contents EDITORIAL 2 by Vasu Gounden FEATURES 3 Assessing the African Union’s Response to the Libyan Crisis by Sadiki Koko and Martha Bakwesegha-Osula 11 Emergent Conflict Resolution at Sea off Africa by Francois Vreÿ 19 Morocco’s Equity and Reconciliation Commission: A New Paradigm for Transitional Justice by Catherine Skroch 27 Crowdsourcing as a Tool in Conflict Prevention by Anne Kahl, Christy McConnell and William Tsuma 35 The Boko Haram Uprising and Insecurity in Nigeria: Intelligence Failure or Bad Governance? by Odomovo S. Afeno 42 Unclear Criteria for Statehood and its Implications for Peace and Stability In Africa by Abebe Aynete 49 A Critical Analysis of Cultural Explanations for the Violence in Jonglei State, South Sudan by Øystein H. Rolandsen and Ingrid Marie Breidlid conflict trends I 1 editorial By vasu gounden The African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of their respective peace negotiations as well as several of Disputes (ACCORD) was established in 1992. In that year the government delegations which have participated in we set as our mission: “ACCORD seeks to encourage and the peace negotiations. We have assisted mediators and promote the constructive resolution of disputes by the facilitators with mediation process strategies and thematic peoples of Africa and so assist in achieving political stability, knowledge, trained election observers in conflict resolution economic recovery and peaceful co-existence within just and skills, prepared peacekeepers in the civilian dimensions democratic societies”. To achieve this mission, over the 20 of peacekeeping, and established and implemented years of its existence ACCORD has employed some 200 full- reconciliation and post-conflict reconstruction initiatives. -

Jonglei State, South Sudan Introduction Key Findings

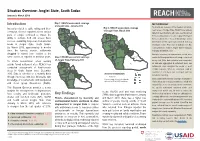

Situation Overview: Jonglei State, South Sudan January to March 2019 Introduction Map 1: REACH assessment coverage METHODOLOGY of Jonglei State, January 2019 To provide an overview of the situation in hard-to- Insecurity related to cattle raiding and inter- Map 3: REACH assessment coverage of Jonglei State, March 2019 reach areas of Jonglei State, REACH uses primary communal violence reported across various data from key informants who have recently arrived parts of Jonglei continued to impact the from, recently visited, or receive regular information ability to cultivate food and access basic Fangak Canal/Pigi from a settlement or “Area of Knowledge” (AoK). services, sustaining large-scale humanitarian Nyirol Information for this report was collected from key needs in Jonglei State, South Sudan. Ayod informants in Bor Protection of Civilians site, Bor By March 2019, approximately 5 months Town and Akobo Town in Jonglei State in January, since the harvest season, settlements February and March 2019. Akobo Duk Uror struggled to extend food rations to the In-depth interviews on humanitarian needs were Twic Pochalla same extent as reported in previous years. Map 2: REACH assessment coverage East conducted throughout the month using a structured of Jonglei State, February 2019 survey tool. After data collection was completed, To inform humanitarian actors working Bor South all data was aggregated at settlement level, and outside formal settlement sites, REACH has Pibor settlements were assigned the modal or most conducted assessments of hard-to-reach credible response. When no consensus could be areas in South Sudan since December found for a settlement, that settlement was not Assessed settlements 2015. -

Wfp & Cp Warehouse Locations

!( (! (! (! (! (! (! (! !( (! (! !( (! (! (! (! (! !( (! (! (! (! (! (! (! (! !( ! (! (! (! ( (! (! (! @ (! (! (! (! (! (! (! !( (! (! (! (! (! (! (! (! (! (! (! (! (! (! (! !( (! 24°0'0"E 25°0'0"E ! 26°0'0"E 27°0'0"E 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 31°0'0"E 32°0'0"E 33°0'0"E 34°0'0"E 35°0'0"E 36°0'0"E 37°0'0"E (! ( Mogara (!Umm Shalkha Tumbo t (! p t s m Qawz Baya e Sineit m t (! 0 (! Buhera (! i 0 l 0 ! Saq An Na`am t ( ! Beringil i ( t ! 0 ( 5 Singeiwa Baddal c Labado m n ! 4 a N N ( ! - ( Nyala (! (! e Dilling 5 ! Shaqq El Khad - ( " " F ) Tumko ! Um Labasa (! ( 7 Ð ) 0 Sigeir Umm Sawum 0 Kalma m ! e ' ! ( ' ( 2 @ Um Kurdus ! Gerger - Kila ! ( ( e 4 Saheib g ! 3 ) 0 ! ( (! 0 !( ( El Lait g a (! Mabrouka Shaqq Al Huja 2 ° ° (! 8 x r Diri Tono (! ! (! a ( x Buddu 72 Akoc x ! T 2 War-Awar 2 ( o (! n 0 5 (! Kumbilah2 p Abu Sufyan t n 0 Aweil North County a 1 1 Wa re h ou s e . (! (! !( ! 1 M Shuwayy (! ( S a Abou Adid Dalami ( 1 Rashad El Roseires (! 6 @ ! Al Muturwed l ( Um Sarir l Ð Twic County ( (! (! ! ! M ( ( ( P Ariath ! s a @ (! ( a Dashi s s ! Ca pa c i tie s 2 0 1 2 t ( Ed Damazin c (! Manyo County 66 Renk H H H o H ! Dago o ( l ! p Wad Hassib o (! Qawz Baya Keikei ( (! ! Renk W R W F L W T ! 71 Akak ( Abu Gheid Ð ID LOCATION STATE (! ( Aw(!eil East County p (! @Î!( Solwong Murr Birkatulli @ 1 Juba CES WFP 0 12 2 3,300 0 10,000 (! (! Ð (! (! Qubba Malualkon ! (! Um@m Labassa Girru p 82 Mayen Pajok 88 Wunrok ( p ! Abu Ajura !( Ma'aliah 1 2 Kapoeta EES WFP 3 10 3 0 0 7,250 (! ( ! Ð (! Um La`ota Abu Karinka (! (! @37 Malualkon (! (! -

Southern Sudan at Odds with Itself

Allen et al. Schomerus ‘I found the report fascinating and also disturbing in equal measure. …While state building efforts are rightly focused on building up structures from the ground they fail to address the primary need to ensure that such institutions are properly reformed to become independent and impartial institutions…To address these pressing issues and to maximise the positive momentum generated SOUTHERN ODD SUDAN AT from the elections and the international focus on Southern Sudan at this time, these issues needs to be discussed publicly with all key states, governments and civil society stakeholders who hold the future of Southern Sudan in their hands. I would urge action sooner rather than later.’ Akbar Khan, Director, Legal & Constitutional Affairs Division, Commonwealth Secretariat ‘The great strength of the report is the accuracy of its voicing of common concerns – it forms an excellent representation of people’s perceptions and experiences, making an important corollary to the current focus on high-level political negotiations and structures. As the report emphasises at the outset, the current focus of Sudanese governments and their international advisors on the technicalities and procedural aspects of planning for the referendum and its outcome needs to be countered by the more holistic approach advocated by this report.’ Cherry Leonardi, Durham University ‘A very important and timely contribution to the current debates…The report offers an invaluable S insight in some of the key issues and dilemma’s Southern Sudan and -

Isaiah Abraham

Tribute To Isaiah Abraham Compiled By of Liberation The PAANLUEL WËL Dark [email protected] Ages http://paanluelwel2011.wordpress.com/ Isaiah Abraham in his own words AU force extension in Darfur, a victory to NCP not to SPLM By Isaiah Abraham* Mar 14, 2006 The drama that led to the extension of African Peacekeeping Forces in Darfur has nothing to do with the Sudan as a whole or SPLM as a party as propagated by those who are against the marginalized people of the Sudan. Darfur is bleeding and should have been saved. The man at the helm of this ‘victory’ is none other than Dr. Lam Akol Ajawin, the Sudanese Foreign Minister from the SPLM Party. Although it is not that easy to satisfy all interests in a coalition the least an astute politician could do or could have done was to compromise not his/her fall back base, no matter the enticement or attraction the players in that political scene. The Minister went out full blast to contradict his boss, President Salva Kiir Mayardit and his colleague in the Government of Southern Sudan (GOSS) Mama Rebecca de Mabior. President Salva was unequivocally pressed that NCP partner is not serious in its willingness to resolve Darfur crisis. Did anybody hear the President or other Southern politicians or the Southern public unease about UN peacekeeping forces intervention in Darfur? Where there demonstrations in the Southern cities in condemnation of the United States or the United Nations or Jan Pronk? Certainly there weren’t and there will not be any protest against presence of UN in any part of the Sudan. -

UNICEF South Sudan Humanitarian Sitrep

UNICEF SOUTH SUDAN SITUATION REPORT 31 July 2018 Mother and child taking part in a cholera and hygiene promotion campaign at Gosene Parish Church in Juba. Photo by Bullen Chol- UNICEF South Sudan Humanitarian Situation Report 01 – 31 JULY 2018: SOUTH SUDAN SITREP #123 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights • The Transitional Government of National Unity (TGoNU) and opposition groups 1.84 million signed an agreement on outstanding issues of governance in Khartoum, Sudan, Internally displaced persons (IDPs) on 05 August. Peace talks are ongoing and the parties must still negotiate (OCHA South Sudan Humanitarian Snapshot, 06 August 2018) several unresolved issues, including the number of states and state boundaries. • The National Girls’ Education Day was celebrated on 17 July to encourage attendance of girls in school. An event organized by UNICEF in Pibor, Boma 2.48 million State was attended by the Governor of Boma State, Minister of General South Sudanese refugees in neighbouring countries Education and Instructions, as well as UN agencies and implementing partners. (OCHA South Sudan Humanitarian Snapshot, • To boost low immunization coverage in South Sudan, UNICEF and partners held 06 August 2018) a series of campaigns entitled “Periodic Intensification of Routine Immunization (PIRI)” in the country. In Lakes State, 300 community mobilizers reached 3,461 7.1 million people with key messages on the importance of measles vaccines and an South Sudanese who are food insecure additional 25,511 people were reached with key messages on PIRI. (May-July -

1St Round Standard Allocation Direct

Requesting Organization : Nile Hope Allocation Type : 1st Round Standard Allocation Primary Cluster Sub Cluster Percentage NUTRITION 100.00 100 Project Title : Provide quality community management of acute malnutrition services, strengthen capacity building and nutrition surveillance in Pigi, Fangak, Akobo (Jonglei) and Leer (Unity) counties. Allocation Type Category : Frontline services OPS Details Project Code : Fund Project Code : SSD-16/HSS10/SA1/N/NGO/771 Cluster : Project Budget in US$ : 267,217.09 Planned project duration : 5 months Priority: Planned Start Date : 01/02/2016 Planned End Date : 30/06/2016 Actual Start Date: 01/02/2016 Actual End Date: 30/06/2016 Project Summary : This project will strive to offer high impact and life-saving nutrition interventions targeting children below five years and PLWs of host communities, IDPs and other vulnerable populations in Fangak, Pigi, Akobo and Leer. The project will have a strong component of community mobilization to enhance active case finding through the screening of PLWs and the under fives and support the necessary referral linkages to the facility/program to ensure treatment of SAM and MAM cases. In the nutrition centres, the nutrition staff will take anthropometric measurements either MUAC or weight and height) and enrol/admit children screened with SAM into the OTP program and receive a week’s ration of RUTF, children screened with MAM will be admitted to the TSFP and receive a two weeks ration of RUSF, the green MUAC/median will be educated on good nutrition practices to maintain -

Ayod, Wau and Pagil, Ayod County, Jonglei State

IRNA Report: Ayod, Wau and Pagil, Ayod County, Jonglei State 7-8 March 2014 This IRNA Report is a product of Inter-Agency Assessment mission conducted and information compiled based on the inputs provided by partners on the ground including; government authorities, affected communities/IDPs and agencies. Situation overview Ayod County is in the northwest part of Jonglei and is comprised of five Payams: Ayod, Mogok, Pajiek, Pagil, Kuachdeng and Wau. Ayod County and its environs are inhabited by Gawar Nuer. It has a population of 139,282 people as per South Sudan Household Census of 2008. Ayod town hosts the county administrative quarters. The county headquarters at the time of the assessment was calm though deserted; the few inhabitants were welcoming to the IRNA team. On 15 February OCHA received reports that up to an estimated 54,000 IDPs were seeking refuge in Ayod County. In response an IRNA mission was launched with COSV taking the lead and convening an Inter cluster Working Group for actors in Ayod County. The area normally has high levels of food insecurity which has worsened over the last two years when flooding destroyed a high proportion of crops and livelihoods. Menime and Haat are Island locations of Ayod, located on the Western part of the county, bordering Fangak County to the North West, Pigi County to the North and Nyirol County on the North East. Since the time of war, these areas have been underserved with basic health care and other services. The area lacks health and immunization coverage. Communication and transport to the islands are a major hindrance in getting adequate information and the only way to access the islands is either by river or air. -

Wfp & Cp Warehouse Locations

!( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !(4 Malualbai !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( 24°0'0"E 25°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 27°0'0"E 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 31°0'0"E 32°0'0"E 33°0'0"E 34°0'0"E 35°0'0"E 36°0'0"E 37°0'0"E !( !( Mogara !(Umm Shalkha Tumbo s !( p T T e Qawz Baya Sineit i M !( t M !( Buhera !( i Saq An Na`am 0 !( Beringil l !( 0 !( i Singeiwa y Labado Baddal 0 T t 0 c !( t N N !( Nyala !( 5 !( Shaqq El Khad Dilling i " " 4 n M a Tumko Um Labasa !( c - Sigeir Umm Sawum !( f 0 0 e Kalma - 5 !( ' ' !( Um Kurdus Gerger a Kila !( !( ) Saheib 6 ) e 0 0 !( !( m !( !( El Lait p !( Mabrouka64 Akoc Shaqq Al Huja 2 4 - ° ° !( Tono !( g e Diri !( a !( 3 Buddu 2 ) !( a 2 2 !( War-Awar Abu Sufyan g r !( Kumbilah2 p C Aweil North County x 8 1 1 !( !( !( x Shuwayy !( Abou Adid !( Dalami a Rashad El Roseires o !( Um Sarir @ Al Muturwed x Ð !( T Twic County t !( 0 !( !( n !( n 0 @ Ariath !( Dashi !( War ehouse 5 s 1 . a a !( Ed Damazin M 1 !( Manyo County ( l Dago ( 6 !( 63 Akak l Wad Hassib P M ( !( p!( Renk a !( Qawz Baya Keikei s !( Capaci ti es 2012 a s 41 Pandit Abu Gheid s !( !( !( !( c t Aweil East County !( Î H H H p o H Solwong Murr Birkatulli l o o !( !( 38 Malualkon @ !( Ð M!(alualkon 71 Mayen Pajok Qubba ID Location State W R W F L W T @ Girru p 78 Wunrok !( !( Umm Labassa Abu Ajura !( Ma'aliah 1 !( !( Ð !( Um La`ota Abu Karinka !( !( @ !( !( 1 Juba CES WFP 1 18 4 4,000 0 13,700 !( !( Abu Ajala @ Edd El Fursan !(Al Marwahah # 2 Ikotos EES WFP 2 0 -

Jonglei State, South Sudan January - March 2020

Situation Overview: Jonglei State, South Sudan January - March 2020 Introduction METHODOLOGY Reported humanitarian needs increased across is likely a consequence of severe flooding Map 1: Assessment coverage in Jonglei State in To provide an indicative overview of the situation Jonglei State throughout the first quarter of which appears to have brought forward January (A), February (B) and March (C), 2020: in hard-to-reach areas of Jonglei State, REACH 2020. An early depletion of food stocks, limited the onset of the lean season from March uses primary data from key informants (KIs) who access to livestock and increasing market to January.3 Moving forward, heavy rains A B have recently arrived from, recently visited, or prices resulted in widespread food insecurity. in the coming months may further reduce receive regular information from a settlement or Moving forward, the existing humanitarian crisis humanitarian access to extremely vulnerable “Area of Knowledge” (AoK). Information for this report was collected from KIs in Bor Protection of could be exacerbated further by the direct and populations in hard-to-reach areas. Civilians (PoC) site, Bor Town and Akobo Town in indirect effects of COVID-19. • The proportion of assessed settlements January, February and March 2020. To inform humanitarian actors working outside reporting protection concerns remained Monthly interviews on humanitarian needs were formal settlement sites, REACH has conducted stable, with 79% reporting most people felt conducted using a structured survey tool. After data collection was completed, all data was assessments of hard-to-reach areas in South safe most of the time in March. However, the 0 - 4.9% aggregated at settlement level, and settlements Sudan since December 2015. -

Ayod County Jonglei State

PAGIL PAYAM, AYOD COUNTY JONGLEI STATE WASH and NFI Assessment Report Conduct a quick assessment of water and sanitation situation together Activity: with identifying needs for ES NFIs in Pagil and surroundings. Location: Pagil N 8' 14140.30 / E 30'4042.75 Duration: 8-14.11.2014 Itinerary: Juba-Rumbek-Pagil-Rumbek-Juba PAH Key counterparts Martin Mawadri William Rot Kok Hygiene & Sanitation Officer RRC Reprentative (Field Polish Humanitarian Action Assistant) Pagil Payam. 0955598182 [email protected] John Guek Payam Administrator (Pagil) Assessment team Joel Francis Lay / Counterparts: WASH Technician John Chol Polish Humanitarian Action PHCU worker 0955390898 [email protected] John Kong Board director for Education Gabriel Kuol Bol and Parjek Rua Local chiefs Meeting key informants - interviews with the RRC representative (William Rot), health worker (John Chol), working with the PHCU being established by COSV, Board Director for education (John Kong) Methodology: Conducted 16 household interviews with both the host communities and IDPs. Conducted two FGDs, one with the women and the other with men Mapping of water sources in Pagil Boma – team has found three boreholes, one functional and two non-functional and has repaired one of the boreholes that was not functioning. The team used UNHAS special flight to Pagil and stayed in RRC compound. In Pagil there is no working network, only satellite phone was available as Logistics: a source of communication. The team also used VHF radios as a way for internal communication Security situation in Pagil is perceived as calm and stable – after the team in Juba contacted with authorities on the ground who confirmed that Security: team is welcomed and will be secure, the ERT went on the ground and did assessment for 7 days.