Functions and Communication Strategies in the Spanish Electoral

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free, Hateful, and Posted: Rethinking First Amendment Protection of Hate Speech in a Social Media World

Boston College Law Review Volume 60 Issue 7 Article 6 10-30-2019 Free, Hateful, and Posted: Rethinking First Amendment Protection of Hate Speech in a Social Media World Lauren E. Beausoleil Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the First Amendment Commons, and the Internet Law Commons Recommended Citation Lauren E. Beausoleil, Free, Hateful, and Posted: Rethinking First Amendment Protection of Hate Speech in a Social Media World, 60 B.C.L. Rev. 2100 (2019), https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol60/iss7/6 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FREE, HATEFUL, AND POSTED: RETHINKING FIRST AMENDMENT PROTECTION OF HATE SPEECH IN A SOCIAL MEDIA WORLD Abstract: Speech is meant to be heard, and social media allows for exaggeration of that fact by providing a powerful means of dissemination of speech while also dis- torting one’s perception of the reach and acceptance of that speech. Engagement in online “hate speech” can interact with the unique characteristics of the Internet to influence users’ psychological processing in ways that promote violence and rein- force hateful sentiments. Because hate speech does not squarely fall within any of the categories excluded from First Amendment protection, the United States’ stance on hate speech is unique in that it protects it. -

Tiktok Y La Creación De Marca Personal

Tiktok y la creación de marca personal Tiktok y la creación de marca personal 1. ÍNDICE - ¿Qué es TikTok? - Historia de TikTok - Evolución de TikTok y expansión imparable (boom durante la pandemia) - Target principal de TikTok (más que la Generación Z) - Las claves del éxito de TikTok - Cómo publicar en TikTok - Consejos para publicar en TikTok - TikTok y su gran engagement - Inversión publicitaria y formatos de anuncios de TikTok - Pasos para hacer una campaña de publicidad serfserve en TikTok - La alianza de TikTok con Shopify: e-commerce - ¿Qué son y para qué sirven el Video Template, Automated Creative Optimisation y Smart Video Soundtrack? - Ventajas de activar una cuenta PRO en TikTok - Otras opciones de privacidad y seguridad en TikTok - Desintoxicación digital: ‘Gestión de Tiempo en Pantalla’, ‘Sincronización familiar’, ‘Modo Restringido’ - Estrategia de influencers, fondo de creadores y compra de monedas virtuales (programa Diamante) - Influencers que más ganan en TikTok - Verificación de cuentas en TikTok - Rumores de espionaje y censura - Cómo crear tu imagen de marca personal en TikTok - Conclusión 2. ¿QUÉ ES TIKTOK? TikTok es una red social china que nace en 2016 y que se basa en la publicación de vídeos cortos y verticales (de entre 3 y 60 segundos) en los que la música y el baile juegan un papel destacado. En China mantiene el nombre original de DouYin, pero en 2018 se extendió por todo el planeta con el nombre de TikTok tras su fusión con la app Musical.ly. Actualmente, se ha convertido en una de las apps más descargadas del mundo por su afinidad y popularidad entre los jóvenes de la Generación Z (nacidos entre 1994 y 2010) y un público de edad cada vez más amplio a raíz del aumento de su popularidad durante la pandemia del Covid- 19. -

JMP Securities Elite 80 Report (Formerly Super 70)

Cybersecurity, Data Management & ,7 Infrastructure FEBRUARY 201 ELITE 80 THE HOTTEST PRIVATELY HELD &<%(5SECURITY, '$7$0$1$*(0(17 AND ,7,1)5$6758&785( COMPANIES &RS\ULJKWWLWLSRQJSZO6KXWWHUVWRFNFRP Erik Suppiger Patrick Walravens Michael Berg [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] (415) 835-3918 (415) 835-8943 (415)-835-3914 FOR DISCLOSURE AND FOOTNOTE INFORMATION, REFER TO JMP FACTS AND DISCLOSURES SECTION. Cybersecurity, Data Management & IT Infrastructure TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ 4 Top Trends and Technological Changes ............................................................................................ 5 Funding Trends ................................................................................................................................ 11 Index by Venture Capital Firm .......................................................................................................... 17 Actifio ................................................................................................................................................ 22 Alert Logic ......................................................................................................................................... 23 AlgoSec ............................................................................................................................................ 24 AnchorFree ...................................................................................................................................... -

A Linguistic Analysis of Their Written Discourse

Spanish politicians in Twitter : A linguistic analysis of their written discourse Ricardo Casañ Pitarch Universitat Politècnica de València (Spain) [email protected] Abstract In Spain, politics is often seen as a profession rather than a service, and thus political discourse should be considered a specialized genre subjected to specific rules and convention. In the 2010s, a new tendency to campaign in politics was the use of social networks, allowing the publication of messages in a virtual environment and the possibility of interacting with other users, Twitter being a popular network. The purpose of this research is to analyze a corpus of 630 tweets published by four Spanish political leaders in their personal Twitter accounts, and consequently to describe their communication style in this social network with the hypothesis that their political views and interests influence their messages. In order to achieve our aim, this research focused on the analysis of written text, emoji, multimedia affordances, and hashtags, and how these elements influenced the politicians’ communication style when dealing with some relevant topics at the time this study was carried out. Keywords: written discourse, Spanish politicians, social networks, Twitter, communication. Resumen Los políticos españoles en Twitter: un análisis lingüístico de su discurso escrito En España, la política suele concebirse como una profesión más que como un servicio, y, por ello, el discurso político debe interpretarse como un género especializado que está sometido a una serie de reglas y convenciones específicas. En la década de los años 2010 surgió una nueva manera de hacer campaña en política mediante el uso de las redes sociales, las cuales permitían la publicación de mensajes cortos en un entorno virtual y la posibilidad de interactuar con otros usuarios. -

Systematic Scoping Review on Social Media Monitoring Methods and Interventions Relating to Vaccine Hesitancy

TECHNICAL REPORT Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy www.ecdc.europa.eu ECDC TECHNICAL REPORT Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy This report was commissioned by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) and coordinated by Kate Olsson with the support of Judit Takács. The scoping review was performed by researchers from the Vaccine Confidence Project, at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (contract number ECD8894). Authors: Emilie Karafillakis, Clarissa Simas, Sam Martin, Sara Dada, Heidi Larson. Acknowledgements ECDC would like to acknowledge contributions to the project from the expert reviewers: Dan Arthus, University College London; Maged N Kamel Boulos, University of the Highlands and Islands, Sandra Alexiu, GP Association Bucharest and Franklin Apfel and Sabrina Cecconi, World Health Communication Associates. ECDC would also like to acknowledge ECDC colleagues who reviewed and contributed to the document: John Kinsman, Andrea Würz and Marybelle Stryk. Suggested citation: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy. Stockholm: ECDC; 2020. Stockholm, February 2020 ISBN 978-92-9498-452-4 doi: 10.2900/260624 Catalogue number TQ-04-20-076-EN-N © European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the -

Muusic: Mashup De Servicios Musicales

Universidad Carlos III de Madrid Campus de Colmenarejo Ingeniería Técnica en Informática de Gestión Proyecto de Fín de Carrera Muusic: mashup de servicios web musicales Alumno: Félix Manuel Lamazares Montes Tutor: César de Pablo Sánchez Noviembre de 2008 2 Agradecimientos Quiero agradecer el apoyo de mi familia durante todos mis estudios: a mis padres Manolo y Maria Jesús; y a mi hermana Paloma. Gracias por ayudarme con la carrera. Gracias a mi padre por leer toda la memoria para corregir errores ortográficos. Gracias a mi tutor César que me ha ayudado mucho; y me ha dado ánimo en momentos de estrés. Gracias también a Pilar y a todos mis amigos que siempre están ahí. 3 0. Índice 0. Índice ............................................................................................................................ 4 1. Introducción.................................................................................................................. 6 1.a. Prefacio.................................................................................................................. 7 1.a.i. Multimedia....................................................................................................... 7 1.a.ii. Servicios Web................................................................................................. 7 1.b. Ámbito................................................................................................................... 8 1.c. Objetivos............................................................................................................... -

Global Feedback and Input on the Facebook Oversight Board for Content Decisions Appendix

Global Feedback and Input on the Facebook Oversight Board for Content Decisions Appendix Appendix A 02 Appendix B 07 Appendix C 26 Appendix D 100 Appendix E 138 Appendix F 177 APPENDIX A Draft Charter: An Oversight Board for Content Decisions Every day, teams at Facebook make difficult decisions about Facebook takes responsibility for our content decisions, what content should stay up and what should come down policies and the values we use to make them The purpose of the board is to provide oversight of how we exercise that As our community has grown to more than 2 billion people, responsibility and to make Facebook more accountable we have come to believe that Facebook should not make so many of those decisions on its own — that people should be The following draft raises questions and considerations, while able to request an appeal of our content decisions to an providing a suggested approach that constitutes a model for independent body the board’s structure, scope and authority It is a starting point for discussion on how the board should be designed To do that, we are creating an external board The board will and formed What the draft does not do is answer every be a body of independent experts who will review Facebook’s proposed question completely or finally most challenging content decisions - focusing on important and disputed cases It will share its decisions transparently and We are actively seeking contributions, opinions and give reasons for them perspectives from around the world on each of the questions outlined below -

Micronarrativas En Instagram

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by E-LIS P RISMA S OCIAL Nº20 LA COMPETENCIA MEDIÁTICA DE LA CIUDADANÍA EN MEDIOS DIGITALES EMERGENTES MARZO 2018 | SECCIÓN TEMÁTICA | PP . 40-57 RECIBIDO : 12/1/2018 – A C E P TA D O : 2/3/2018 MICRONARRATIVAS EN INSTAGRAM: ANÁLISIS DEL STORYTELLING AUTOBIOGRÁFICO Y DE LA PROYECCIÓN DE IDENTIDADES DE LOS UNIVERSITARIOS DEL ÁMBITO DE LA COMUNICACIÓN MICRO-NARRATIVES ON INSTAGRAM: ANALYSIS OF THE AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL STORYTELLING AND THE PROJECTION OF IDENTITIES OF THE DEGREES IN THE FIELD OF COMMUNICATION PATRICIA DE-CASAS-MORENO / [email protected] UNIVERSIDAD DE NEBRIJA, ESPAÑA SANTIAGO TEJEDOR-CALVO / [email protected] UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE BARCELONA, ESPAÑA LUIS M. ROMERO-RODRÍGUEZ / [email protected] ESAI BUSINESS SCHOOL, UNIVERSIDAD ESPÍRITU SANTO / UNIVERSIDAD INTERNACIONAL DE LA RIOJA, ESPAÑA ESTA INVESTIGACIÓN ESTÁ ENMARCADA EN EL PROYECTO I+D “COmpETENCIAS MEDIÁTICAS DE LA CIUDADANÍA EN MEDIOS DIGITALES EMERGENTES (SMARTPHONES Y TABLETS): PRÁCTICAS INNOVADORAS Y ESTRATEGIAS EDUCOMUNICATIVAS EN CONTEXTOS MÚLTIPLES” CON CLAVE EDU-2015-64015-C3-1-R DEL MINISTERIO DE ECONOMÍA Y COmpETITIVIDAD DE ESPAÑA (MINECO/FEDER). prisma social revista de ciencias sociales P ATRICIA DE - C ASAS - M ORENO , S ANTIAGO T EJEDOR - C ALVO Y L UIS M . R OMERO - R ODRÍGUEZ RESUMEN ABSTRACT El estudio de las redes sociales entre los jóvenes The study of social networks among young Internet internautas se ha convertido en una línea de users has become a growing line of research. There investigación en crecimiento. Existen numerosas are numerous studies, however, has analyzed the investigaciones al respecto, sin embargo, apenas type of content (topics and approaches) published se ha analizado el tipo de contenidos (temáticas and, especially, the characteristic profiles in the y enfoques) que publican y, especialmente, articulation of stories. -

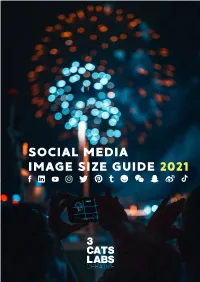

Social Media Image Sizes 2021

SOCIAL MEDIA IMAGE SIZE GUIDE 2021 FACEBOOK Profile Image: 180 x 180 px Cover Photo: 820 x 312 px Image Guidelines Image Guidelines Must be at least 180 x 180 pixels. 820 x 312 px Appears on page at 820 x 312 pixels. Photo will appear on page as 170 x 170 Minimum size of 400 x 150 pixels. pixels. Smartphones display at 640 x 360 pixels. Photo thumbnail will appear throigjout 180 x 180 px Facebook as 32 x 32 pixels. Images or text may display best as PNG file. 128 x 128 pixels on smartphones. Profile pictures are located 24 pixels from the left, 24 pixels from the bottom, and 196 pixels from the top of your cover Shared Images: 1200 x 630 px photo on smartphones. This image represents your brand on Image Guidelines Facebook. The square photo will appear on your timeline layered over the cover Recommended upload size of 1200 x 530 photo. pixels. The profile image also appears when you `1200 x 630 px Will appear in feed at max width of 470 post on other walls, comment, or when pixels (1:1 scale) searched using Facebook’s Open Graph. Appears on page at max width of 504 pixels (max 1:1 scale display) Shared Link: 1200 x 628 px `1200 x 628 px Image Guidelines Recommended uplaod size of 1200 x 628 pixels. Highlighted Image: 1200 x 717 px Square photo minimumum of 154 x 154 pixels in feed. Square photo of minimum 116 x 116 Image Guidelines pixels on page. Rectangualr photo minimum 484 x 252 Appears on your page at 843 x 504 pixels. -

Music Recommendation and Discovery in the Long Tail

MUSIC RECOMMENDATION AND DISCOVERY IN THE LONG TAIL Oscar` Celma Herrada 2008 c Copyright by Oscar` Celma Herrada 2008 All Rights Reserved ii To Alex and Claudia who bring the whole endeavour into perspective. iii iv Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Xavier Serra, for giving me the opportunity to work on this very fascinating topic at the Music Technology Group (MTG). Also, I want to thank Perfecto Herrera for providing support, countless suggestions, reading all my writings, giving ideas, and devoting much time to me during this long journey. This thesis would not exist if it weren’t for the the help and assistance of many people. At the risk of unfair omission, I want to express my gratitude to them. I would like to thank all the colleagues from MTG that were —directly or indirectly— involved in some bits of this work. Special mention goes to Mohamed Sordo, Koppi, Pedro Cano, Mart´ın Blech, Emilia G´omez, Dmitry Bogdanov, Owen Meyers, Jens Grivolla, Cyril Laurier, Nicolas Wack, Xavier Oliver, Vegar Sandvold, Jos´ePedro Garc´ıa, Nicolas Falquet, David Garc´ıa, Miquel Ram´ırez, and Otto W¨ust. Also, I thank the MTG/IUA Administration Staff (Cristina Garrido, Joana Clotet and Salvador Gurrera), and the sysadmins (Guillem Serrate, Jordi Funollet, Maarten de Boer, Ram´on Loureiro, and Carlos Atance). They provided help, hints and patience when I played around with the machines. During my six months stage at the Center for Computing Research of the National Poly- technic Institute (Mexico City) in 2007, I met a lot of interesting people ranging different disciplines. -

Ad-Free Social Network Ello Goes Public 18 June 2015

Ad-free social network Ello goes public 18 June 2015 collection by other networks coming to the forefront of the news, the timing of our app release couldn't be better." Ello has upgraded the service to include new ways to find friends, full search, real-time alerts, private messaging, private groups and "loves" instead of likes. It received $5.5 million in funding last year as it changed its charter to back a promise to remain ad- free, becoming a "public benefit corporation." While the services is free, Its future plans include premium features which would be paid. Ello was launched by a group of artists and programmers led by Budnitz, whose previous Ello, the ad-free social network which gained experience includes designing bicycles and toys. prominence last year with an invitation-only launch, announced it was opening to the public with an application for iPhone users © 2015 AFP Ello, the ad-free social network which gained prominence last year with an invitation-only launch, announced Thursday it was opening to the public with an application for iPhone users. The startup got attention with its "anti-Facebook" policy of promising to never use advertising or to sell customer data to third parties. Last September, a surge in interest made Ello membership a hot ticket, with invitations selling on eBay at prices up to $500. In announcing the public launch, Ello provided no details on numbers of members but said there were "millions" using the platform. "The new app is beautiful with dozens of unique features," said Ello co-founder and chief executive Paul Budnitz. -

LLNE Goes Public

LLNENews Newsletter of the Law Librarians of New England Volume 31, Issue 2, 2014 LLNE Goes Public This year, with the goal of increasing law, estate plan- access to legal information in ning, and land- Encouraged by the lord-tenant law, positive response from our communities, the Service to name a few. Committee selected a theme of Guided in part the Massachusetts book by the AALL’s drive, we decided to Outreach to Public Libraries. Public Library Toolkit1, we expand our efforts and developed a create collections for all wish list of titles by Catherine Biondo and Rebecca Martin to create a mini- New England states. collection for a or our first project, we chose to organize a book drive Massachusetts of legal reference-type books on common topics we public library and launched our book drive at the 2013 Fthought might be of interest to many, including family fall meeting at the Social Law Library. Encouraged by the positive response from the Massa- chusetts book drive, we decided to expand our efforts and create collections for all New England states. In advance of the 2014 spring meeting at University of Connecticut School of Law, we coordinated with the Southern New England Law Library Association (SNELLA) to assemble a list of titles for a Connecticut public library, therefore tying in the book drive with the meeting’s locale. Later, we advertised the drive with fliers for each state on our committee’s webpage2 and at the LLNE table at AALL in San Antonio. As a committee, we have been hard at work on the various aspects of running the drive, including creat- ing the wish lists of books for each state; advertising the drive to the LLNE membership and collecting book and monetary donations; collaborating with meeting hosts and other librarian organizations; soliciting book donations and discounts from publishers and vendors; and identifying Continued on page 10 CONTENTS Featured Articles In Every Issue LLNE GOES PUBLIC 1 EDITOR’S NOTE 3 5 QUESTIONS FOR..