Journal of Hymenoptera Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Species Delimitation and Phylogeography of Aphonopelma Hentzi (Araneae, Mygalomorphae, Theraphosidae): Cryptic Diversity in North American Tarantulas

Species Delimitation and Phylogeography of Aphonopelma hentzi (Araneae, Mygalomorphae, Theraphosidae): Cryptic Diversity in North American Tarantulas Chris A. Hamilton1*, Daniel R. Formanowicz2, Jason E. Bond1 1 Auburn University Museum of Natural History and Department of Biological Sciences, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama, United States of America, 2 Department of Biology, The University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, Texas, United States of America Abstract Background: The primary objective of this study is to reconstruct the phylogeny of the hentzi species group and sister species in the North American tarantula genus, Aphonopelma, using a set of mitochondrial DNA markers that include the animal ‘‘barcoding gene’’. An mtDNA genealogy is used to consider questions regarding species boundary delimitation and to evaluate timing of divergence to infer historical biogeographic events that played a role in shaping the present-day diversity and distribution. We aimed to identify potential refugial locations, directionality of range expansion, and test whether A. hentzi post-glacial expansion fit a predicted time frame. Methods and Findings: A Bayesian phylogenetic approach was used to analyze a 2051 base pair (bp) mtDNA data matrix comprising aligned fragments of the gene regions CO1 (1165 bp) and ND1-16S (886 bp). Multiple species delimitation techniques (DNA tree-based methods, a ‘‘barcode gap’’ using percent of pairwise sequence divergence (uncorrected p- distances), and the GMYC method) consistently recognized a number of divergent and genealogically exclusive groups. Conclusions: The use of numerous species delimitation methods, in concert, provide an effective approach to dissecting species boundaries in this spider group; as well they seem to provide strong evidence for a number of nominal, previously undiscovered, and cryptic species. -

Metal Acquisition in the Weaponized Ovipositors of Aculeate Hymenoptera

Zoomorphology https://doi.org/10.1007/s00435-018-0403-1 ORIGINAL PAPER Harden up: metal acquisition in the weaponized ovipositors of aculeate hymenoptera Kate Baumann1 · Edward P. Vicenzi2 · Thomas Lam2 · Janet Douglas2 · Kevin Arbuckle3 · Bronwen Cribb4,5 · Seán G. Brady6 · Bryan G. Fry1 Received: 17 October 2017 / Revised: 12 March 2018 / Accepted: 17 March 2018 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract The use of metal ions to harden the tips and edges of ovipositors is known to occur in many hymenopteran species. However, species using the ovipositor for delivery of venom, which occurs in the aculeate hymenoptera (stinging wasps, ants, and bees) remains uninvestigated. In this study, scanning electron microscopy coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray analysis was used to investigate the morphology and metal compositional differences among aculeate aculei. We show that aculeate aculei have a wide diversity of morphological adaptations relating to their lifestyle. We also demonstrate that metals are present in the aculei of all families of aculeate studied. The presence of metals is non-uniform and concentrated in the distal region of the stinger, especially along the longitudinal edges. This study is the first comparative investigation to document metal accumulation in aculeate aculei. Keywords Scanning electron microscopy · Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy · EDS · Aculeata · Aculeus · Cuticle · Metal accumulation Introduction with the most severe responses (as perceived by humans) delivered by taxa including bullet ants (Paraponera), taran- Aculeata (ants, bees, and stinging wasps) are the most con- tula hawk wasps (Pepsis), and armadillo wasps (Synoeca) spicuous of the hymenopteran insects, and are known pre- (Schmidt 2016). -

A Guide to Arthropods Bandelier National Monument

A Guide to Arthropods Bandelier National Monument Top left: Melanoplus akinus Top right: Vanessa cardui Bottom left: Elodes sp. Bottom right: Wolf Spider (Family Lycosidae) by David Lightfoot Compiled by Theresa Murphy Nov 2012 In collaboration with Collin Haffey, Craig Allen, David Lightfoot, Sandra Brantley and Kay Beeley WHAT ARE ARTHROPODS? And why are they important? What’s the difference between Arthropods and Insects? Most of this guide is comprised of insects. These are animals that have three body segments- head, thorax, and abdomen, three pairs of legs, and usually have wings, although there are several wingless forms of insects. Insects are of the Class Insecta and they make up the largest class of the phylum called Arthropoda (arthropods). However, the phylum Arthopoda includes other groups as well including Crustacea (crabs, lobsters, shrimps, barnacles, etc.), Myriapoda (millipedes, centipedes, etc.) and Arachnida (scorpions, king crabs, spiders, mites, ticks, etc.). Arthropods including insects and all other animals in this phylum are characterized as animals with a tough outer exoskeleton or body-shell and flexible jointed limbs that allow the animal to move. Although this guide is comprised mostly of insects, some members of the Myriapoda and Arachnida can also be found here. Remember they are all arthropods but only some of them are true ‘insects’. Entomologist - A scientist who focuses on the study of insects! What’s bugging entomologists? Although we tend to call all insects ‘bugs’ according to entomology a ‘true bug’ must be of the Order Hemiptera. So what exactly makes an insect a bug? Insects in the order Hemiptera have sucking, beak-like mouthparts, which are tucked under their “chin” when Metallic Green Bee (Agapostemon sp.) not in use. -

PDF Download Wasp Ebook Free Download

WASP PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Eric Frank Russell | 192 pages | 09 May 2013 | Orion Publishing Co | 9780575129047 | English | London, United Kingdom 25 Types of Wasps and Hornets - ProGardenTips Megascolia procer , a giant solitary species from Java in the Scoliidae. This specimen's length is 77mm and its wingspan is mm. Megarhyssa macrurus , a parasitoid. The body of a female is 50mm long, with a c. Tarantula hawk wasp dragging an orange-kneed tarantula to her burrow; it has the most painful sting of any wasp. Of the dozens of extant wasp families, only the family Vespidae contains social species, primarily in the subfamilies Vespinae and Polistinae. All species of social wasps construct their nests using some form of plant fiber mostly wood pulp as the primary material, though this can be supplemented with mud, plant secretions e. Wood fibres are gathered from weathered wood, softened by chewing and mixing with saliva. The placement of nests varies from group to group; yellow jackets such as Dolichovespula media and D. Other wasps, like Agelaia multipicta and Vespula germanica , like to nest in cavities that include holes in the ground, spaces under homes, wall cavities or in lofts. While most species of wasps have nests with multiple combs, some species, such as Apoica flavissima , only have one comb. The vast majority of wasp species are solitary insects. There are some species of solitary wasp that build communal nests, each insect having its own cell and providing food for its own offspring, but these wasps do not adopt the division of labour and the complex behavioural patterns adopted by eusocial species. -

Os Nomes Galegos Dos Insectos 2020 2ª Ed

Os nomes galegos dos insectos 2020 2ª ed. Citación recomendada / Recommended citation: A Chave (20202): Os nomes galegos dos insectos. Xinzo de Limia (Ourense): A Chave. https://www.achave.ga /wp!content/up oads/achave_osnomesga egosdos"insectos"2020.pd# Fotografía: abella (Apis mellifera ). Autor: Jordi Bas. $sta o%ra est& su'eita a unha licenza Creative Commons de uso a%erto( con reco)ecemento da autor*a e sen o%ra derivada nin usos comerciais. +esumo da licenza: https://creativecommons.org/ icences/%,!nc-nd/-.0/deed.g . 1 Notas introdutorias O que cont n este documento Na primeira edición deste recurso léxico (2018) fornecéronse denominacións para as especies máis coñecidas de insectos galegos (e) ou europeos, e tamén para algúns insectos exóticos (mostrados en ám itos divulgativos polo seu interese iolóxico, agr"cola, sil!"cola, médico ou industrial, ou por seren moi comúns noutras áreas xeográficas)# Nesta segunda edición (2020) incorpórase o logo da $%a!e ao deseño do documento, corr"xese algunha gralla, reescr" ense as notas introdutorias e engádense algunhas especies e algún nome galego máis# &n total, ac%éganse nomes galegos para 89( especies de insectos# No planeta téñense descrito aproximadamente un millón de especies, e moitas están a"nda por descubrir# Na )en"nsula * érica %a itan preto de +0#000 insectos diferentes# Os nomes das ol oretas non se inclúen neste recurso léxico da $%a!e, foron o xecto doutro tra allo e preséntanse noutro documento da $%a!e dedicado exclusivamente ás ol oretas, a!ela"ñas e trazas . Os nomes galegos -

Adaptations of Insects at Cloudbridge Nature Reserve, Costa Rica

Adaptations of Insects at Cloudbridge Nature Reserve, Costa Rica Aiden Vey Cloudbridge Nature Reserve July 2007 Introduction Costa Rica’s location between North and South America, its neotropical climate and variety of elevations and habitats makes it one of the biodiversity hotspots of the world. Despite being only 51,100km² in size, it contains about 5% (505,000) of the world’s species. Of these, 35,000 insect species have been recorded and estimates stand at around 300,000. The more well known insects include the 8,000 species of moth and 1,250 butterflies - almost 10% of the world total, and 500 more than in the USA! Other abundant insects of Costa Rica include ants, beetles, wasps and bees, grasshoppers and katydids. The following article presents a select few aspects of the insect life found at Cloudbridge, a nature reserve in the Talamanca mountain range. Relationships Insects play many important roles in Costa Rica, including pollination of the bountiful flora and as a food supply for many other organisms. The adult Owl butterfly (Caligo atreus, shown at right) feeds on many Heliconiaceae and Musaceae (banana) species, in particular on the rotting fruit. They are pollinators of these plants, but also use the leaves to lay eggs on. When hatched, the larvae remain on the plant and eat the leaves. Being highly gregarious, they can cause significant damage, and are considered as pests (especially in banana plantations). However, there are a number of insects that parasitise the Caligo larvae, including the common Winthemia fly (left) and Trichogramma and Ichneumon wasps, which act as biological control agents. -

Sphecos: a Forum for Aculeate Wasp Researchers

APRIL 1991 SPHECOS A FORUM FOR ACUlEATE WASP. RESEARCHERS MINUTIAE FROM THE ty• of digger wasps had a slightly une MUD D'AUB ARNOLDS. MENKE, Edhor ven distribution while the •nesting Tony Nuhn, Assistant Editor com Systematic Entomology Labratory munity• had a more patchy distnbution. Still no official word from the old Agricultural Research Senrice,USDA Sphecid communHies were more di· BMNH regarding personnel changes, c/o National Museum of Natural History verse on patches w~h relatively low but as of last November, Nigel Fergus Smithsonian I1Stitution, Washington, DC 20560 plant diversHy and cover. Diversity de· FAX: (202) son (a cynipoidist) was put in charge 786-9422 Phone: (202) 382-t803 creased in response to watering and of Coleoptera. Nigel informed me that watering combined wHh mechanical iso Tom Huddleston is now in charge of lation and increased after removal oi Hymenoptera. By the time you receive the upper layer of soil and plants. this issue of Sphecos, Mick Day may RESEARCH NEWS no longer be employed at The Natural lynn Kimsey (Dept. of Entomology, Alexander V. Antropov History Museum (aka BMNH). (Zoological Univ. of California. Davis, CA 95616, Museum of the Moscow lomonosov George Eickwort of Cornell Universi USA) reports "I am revising the wasp State ty is the President-elect of the Interna University, Herzen Street 6, Mos family Tiphiidae for the world, and have cow K-9 I tional Society of Hymenopterists. The 03009 USSR) has described begun sorting all of our miscellaneous a new genus of Crabroninae Society's second quadrennial meeting from Bra tiphiid wasps to genus and species. -

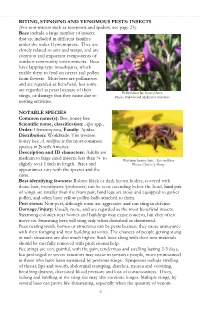

BITING, STINGING and VENOMOUS PESTS: INSECTS (For Non-Insects Such As Scorpions and Spiders, See Page 23)

BITING, STINGING AND VENOMOUS PESTS: INSECTS (For non-insects such as scorpions and spiders, see page 23). Bees include a large number of insects that are included in different families under the order Hymenoptera. They are closely related to ants and wasps, and are common and important components of outdoor community environments. Bees have lapping-type mouthparts, which enable them to feed on nectar and pollen from flowers. Most bees are pollinators and are regarded as beneficial, but some are regarded as pests because of their Pollination by honey bees stings, or damage that they cause due to Photo: Padmanand Madhavan Nambiar nesting activities. NOTABLE SPECIES Common name(s): Bee, honey bee Scientific name, classification: Apis spp., Order: Hymenoptera, Family: Apidae. Distribution: Worldwide. The western honey bee A. mellifera is the most common species in North America. Description and ID characters: Adults are medium to large sized insects, less than ¼ to Western honey bee, Apis mellifera slightly over 1 inch in length. Sizes and Photo: Charles J. Sharp appearances vary with the species and the caste. Best identifying features: Robust black or dark brown bodies, covered with dense hair, mouthparts (proboscis) can be seen extending below the head, hind pair of wings are smaller than the front pair, hind legs are stout and equipped to gather pollen, and often have yellow pollen-balls attached to them. Pest status: Non-pest, although some are aggressive and can sting in defense. Damage/injury: Usually none, and are regarded as the most beneficial insects. Swarming colonies near homes and buildings may cause concern, but they often move on. -

Die Hymenopterengruppe Der Sphecinen. I

©Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Die Hymenopterengruppe der Sphecinen. I. Monographie der natürlichen Gattung Sphex Linné (sens. lat.). Von Frani Friedr. Kohl. Mit fünf lithogr. Tafeln (Nr. VIII—XII). I. Abtheilung. Diese hymenopterologische Schrift ist eine Abhandlung über die Sphecinen, einer Gruppe enger verwandter Raubwespengattungen, mit einer monographischen Be- arbeitung der bisher von den Autoren festgehaltenen Gattungen Chlorion, Parasphex, Harpactopus, Priononyx, Isodontia, Sphex und Pseudosphex, welche jedoch, vom Standpunkte der jüngeren wissenschaftlichen Systematik beurtheilt, alle zusammen nur Artengruppen einer einzigen natürlichen Gattung — Sphex s. 1. — sind. Eine Monographie darüber gibt es dermalen nicht, es wäre denn, man wollte die Bearbeitung der Sphecinen von Dahlbom in Hymenoptera europaea I, oder jene von Le pelletier in Hist, natur. Ins. Hym. III, beide vom Jahre 1845, als solche ansehen. Diese sind indessen hinsichtlich der Zahl der beschriebenen Arten, der Beschaffen- heit der Beschreibungen, besonders aber in Betreff der Auffassung des verwandtschaft- lichen Verhältnisses der Formen ganz ungenügend. Die Zahl der Artbeschreibungen hat sich seit dem Erscheinen jener Werke mehr als verdreifacht. Die Arbeiten anderer Autoren über Sphexe behandeln diese Hautflügler blos von einem beschränkten Gebiete oder mehr in faunistischer Weise oder bringen nur Neu- beschreibungen und überragen mit Ausnahme der Abhandlung Taschenberg's »Die Sphegiden des zoologischen Museums der Universität zu Halle« ') und jener Patton's »Some characters useful in the study of the Sphecidae«2) die früher genannten Werke in keinerlei Weise. Der im Jahre i885 in Természetrajzi Füzetek IX, pag. 54 (Budapest) veröffent- lichte Aufsatz »Die Gattungen der Sphecinen und die paläarktischen Sphex-Arten« ist als Vorstudie zu dieser Monographie zu betrachten. -

The Diversity and Evolution of Pollination Systems in Large Plant Clades: Apocynaceae As a Case Study

Annals of Botany 123: 311–325, 2019 doi: 10.1093/aob/mcy127, available online at www.academic.oup.com/aob PART OF A SPECIAL ISSUE ON ECOLOGY AND EVOLUTION OF PLANT REPRODUCTION The diversity and evolution of pollination systems in large plant clades: Apocynaceae as a case study Jeff Ollerton1*, Sigrid Liede-Schumann2, Mary E. Endress3, Ulrich Meve2, André Rodrigo Rech4, Adam Shuttleworth5, Héctor A. Keller6, Mark Fishbein7, Leonardo O. Alvarado-Cárdenas8, 9 10 11 12 13 Felipe W. Amorim , Peter Bernhardt , Ferhat Celep , Yolanda Chirango , Fidel Chiriboga-Arroyo , Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/aob/article-abstract/123/2/311/5067583 by guest on 25 January 2019 Laure Civeyrel14, Andrea Cocucci15, Louise Cranmer1, Inara Carolina da Silva-Batista16, Linde de Jager17, Mariana Scaramussa Deprá18, Arthur Domingos-Melo19, Courtney Dvorsky10, Kayna Agostini20, Leandro Freitas21, Maria Cristina Gaglianone18, Leo Galetto22, Mike Gilbert23, Ixchel González-Ramírez8, Pablo Gorostiague24, David Goyder23, Leandro Hachuy-Filho9, Annemarie Heiduk25, Aaron Howard26, Gretchen Ionta27, Sofia C. Islas-Hernández8, Steven D. Johnson5, Lize Joubert17, Christopher N. Kaiser-Bunbury28, Susan Kephart29, Aroonrat Kidyoo30, Suzanne Koptur27, Cristiana Koschnitzke16, Ellen Lamborn1, Tatyana Livshultz31, Isabel Cristina Machado19, Salvador Marino15, Lumi Mema31, Ko Mochizuki32, Leonor Patrícia Cerdeira Morellato33, Chediel K. Mrisha34, Evalyne W. Muiruri35, Naoyuki Nakahama36, Viviany Teixeira Nascimento37, Clive Nuttman38, Paulo Eugenio Oliveira39, Craig I. Peter40, Sachin Punekar41, Nicole Rafferty42, Alessandro Rapini43, Zong-Xin Ren44, Claudia I. Rodríguez-Flores45, Liliana Rosero46, Shoko Sakai32, Marlies Sazima47, Sandy-Lynn Steenhuisen48, Ching-Wen Tan49, Carolina Torres22, Kristian Trøjelsgaard50, Atushi Ushimaru51, Milene Faria Vieira52, Ana Pía Wiemer53, Tadashi Yamashiro54, Tarcila Nadia55, Joel Queiroz56 and Zelma Quirino57 Affiliations are listed at the end of the paper *For correspondence. -

Prairie Partner News Sept2018

July - Prairie Partner News 2018 Sept A publication for and about Blackland Prairie Texas Master Naturalists The “Summer Edition” of our newsletter is about to be “hot off the press” and I know it will be just a “tip of the iceberg” of all the amazing activities that our chapter has been up to these past few months, from education to restoration projects and completing the necessary training to join our wonderful cause. I congratulate all of your efforts and encourage you to take the time to share photos, written reports, reflections, poems and more for publication in our next newsletter. Special kudos to our fearless leader, Mike Roome and Dave Powell for their 4000 plus hours of service, for those meeting other key milestones and our class of 2018 graduates! Greg Tonian, Editor “When I look at the earth in pictures taken from space, I see no boundaries, no border patrols, No sign of ownership of the land or the seas., Or the mountains, Or the lakes or rivers; I feel like a planetary citizen.” Shurli Grant, Planetary Citizens in Rainbow Published in Meditations of Ralph Waldo Emerson: Into a Green Future by Chris Highland June meadow scene at Heard Natural Science Museum and Wildlife Sanctuary CONGRATULATIONS CLASS OF 2018! April 27 – May 3 Flora and Fauna of the Blackland Prairie Your classes are nearly done, a few field trips to go. Think of the knowledge that you can now bestow. The speakers were informative and expanded your view; Some reinforced topics you already knew. But now you have resources and much more: You’ve increased your friendships by nearly two score. -

TAWNY CRAZY ANTS Anewsletter for the Belterra the Tawny Crazy Ant, Formerly Known As the to Remove Anything That Is Not Necessary

the THE BULLETIN BulletiNBelterra Community News August 2015 Volume 9, Issue 8 News for the Residents of Belterra WELCOME TO BELTERRA HOA NEWS TAWNY CRAZY ANTS ANewsletter for the Belterra The Tawny crazy ant, formerly known as the to remove anything that is not necessary. Community Rasberry crazy ant, was originally found in Harris Alter moisture conditions (crazy ants prefer The Bulletin is a monthly County in 2002. It is currently confirmed in 27 moist, humid conditions)- reduce watering, repair newsletter mailed to all Texas counties. any leaks, improve drainage Belterra residents. Each Tawny crazy ants have a cyclical population Eliminate honeydew producers from area. newsletter will be filled with level throughout the year with populations Crazy ants tend honeydew producers such as valuable information about peaking in late summer, decreasing in the fall aphids, whiteflies, hoppers, mealybugs and scale the community, local area and then beginning to build again in the spring. insects. activities, school information, Tawny crazy ants are capable of biting, but do Use pesticide sprays to treat infested areas- and more. NOT sting like fire ants. They are mostly nuisance under rocks, along landscape edging, etc. Pesticide If you are involved with pests, but can reach extraordinary population sprays can also be used to create a barrier around a school group, play group, levels (in the millions) and can become a problem the outside of the home. Piles of dead ants may scouts, sports team, social when getting into electrical equipment. Tawny build up in treated areas, so they must be removed group, etc., and would like crazy ants do not have nests or mounds like to keep the barrier maintained.