In the Himalayas Interests, Conflicts, and Negotiations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Augusta Lexington

LEXINGTON WV KY VA TN GA SC AUGUSTA TRIAD MACON CHARLESTON TOP 10 UNREACHED PEOPLE GROUPS IN THE TRIAD 919.332.0459 [email protected] 1. AMHARIC 2. ARAB-LEVANT 3. ARAB-SUDANESE 4. BHUTANESE 5. HAUSA 6. HINDI 7. NEPALI 8. PUNJABI 9. URDU 10. VIETNAMESE Check out the people group map of the Triad: ncbaptist.org/prayermap Become More Involved: MICHAEL SOWERS Triad Strategy Coordinator, ETHIOPIA, Amharic HORN OF AFRICA God brings the Amhara people to us from Ethiopia, in the Horn of Africa. The Amhara people living in the U.S. maintain close ties to the Amhara people living in and around Washington, D.C. Most Amhara embrace either Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity or Islam. Over the years, the Amhara people have mixed Christianity with the worship of deceased saints and have embraced an unorthodox view of Christ. Most have no real knowledge of the Scriptures. In North Carolina, the majority of the men work in limo, taxi or convenience store businesses, while the women work in restaurants and salons or grocery and retail stores. The Amhara people highly value their unique food and culture, so even if their population is very small, they quickly establish a grocery store and restaurant to meet the needs of the Amharic-Ethiopian community. The central influence of these Amharic-Ethiopian stores and restaurants makes them a good location to meet the Amhara people. Religion: Sunni Islam, Ethiopian Orthodox Discovered: Charlotte, Triad, Triangle Estimated NC Population: 5,400 Where could you find the Amharic? bit.ly/amharictriad PALESTINE, Arab-Levant MIDDLE EAST God brings the Arab-Levant people to us from the Fertile Crescent, the land along a northward arc between the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean Sea. -

Four Ana and One Modem House: a Spatial Ethnography of Kathmandu's Urbanizing Periphery

I Four Ana and One Modem House: A Spatial Ethnography of Kathmandu's Urbanizing Periphery Andrew Stephen Nelson Denton, Texas M.A. University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies, December 2004 B.A. Grinnell College, December 2000 A Disse11ation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology University of Virginia May 2013 II Table of Contents Introduction Chapter 1: An Intellectual Journey to the Urban Periphery 1 Part I: The Alienation of Farm Land 23 Chapter 2: From Newar Urbanism to Nepali Suburbanism: 27 A Social History of Kathmandu’s Sprawl Chapter 3: Jyāpu Farmers, Dalāl Land Pimps, and Housing Companies: 58 Land in a Time of Urbanization Part II: The Householder’s Burden 88 Chapter 4: Fixity within Mobility: 91 Relocating to the Urban Periphery and Beyond Chapter 5: American Apartments, Bihar Boxes, and a Neo-Newari 122 Renaissance: the Dual Logic of New Kathmandu Houses Part III: The Anxiety of Living amongst Strangers 167 Chapter 6: Becoming a ‘Social’ Neighbor: 171 Ethnicity and the Construction of the Moral Community Chapter 7: Searching for the State in the Urban Periphery: 202 The Local Politics of Public and Private Infrastructure Epilogue 229 Appendices 237 Bibliography 242 III Abstract This dissertation concerns the relationship between the rapid transformation of Kathmandu Valley’s urban periphery and the social relations of post-insurgency Nepal. Starting in the 1970s, and rapidly increasing since the 2000s, land outside of the Valley’s Newar cities has transformed from agricultural fields into a mixed development of planned and unplanned localities consisting of migrants from the hinterland and urbanites from the city center. -

Custom, Law and John Company in Kumaon

Custom, law and John Company in Kumaon. The meeting of local custom with the emergent formal governmental practices of the British East India Company in the Himalayan region of Kumaon, 1815–1843. Mark Gordon Jones, November 2018. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University. © Copyright by Mark G. Jones, 2018. All Rights Reserved. This thesis is an original work entirely written by the author. It has a word count of 89,374 with title, abstract, acknowledgements, footnotes, tables, glossary, bibliography and appendices excluded. Mark Jones The text of this thesis is set in Garamond 13 and uses the spelling system of the Oxford English Dictionary, January 2018 Update found at www.oed.com. Anglo-Indian and Kumaoni words not found in the OED or where the common spelling in Kumaon is at a great distance from that of the OED are italicized. To assist the reader, a glossary of many of these words including some found in the OED is provided following the main thesis text. References are set in Garamond 10 in a format compliant with the Chicago Manual of Style 16 notes and bibliography system found at http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org ii Acknowledgements Many people and institutions have contributed to the research and skills development embodied in this thesis. The first of these that I would like to acknowledge is the Chair of my supervisory panel Dr Meera Ashar who has provided warm, positive encouragement, calmed my panic attacks, occasionally called a spade a spade but, most importantly, constantly challenged me to chart my own way forward. -

A Study of Contemporary Nepalese Muslim Political Discourse

Politics of ‘Inclusiveness’: A Study of Contemporary Nepalese Muslim Political Discourse Nazima Parveen Visiting Scholar, CNAS University of Kathmandu, Nepal Abstract The project traces how different communities of Nepal have been conceptualized as a nation. It offers a definition of their intrinsic relationship with different forms of Nepali state. The project examines the idea of inclusiveness—an idea which has recently gained popularity after the rise of the Maoist democratic regime. Inclusiveness has been regarded as a point of reference in looking at various political/administrative discourses which define Nepal as a singular entity and provide legitimate conceptual spaces to minorities. Beyond the conventional mainstream/minority discourse binary, the project traces the genealogy of the concept of minority. It examines issues and concerns related to Muslims that pose a challenge to the formation of the erstwhile Hindu kingdom of Nepal, as well as the newly established democratic republican state. This Muslim-centric approach is also linked with the policy discourse on preferential treatment, a demand rife with significant political overtones in the post-1990 transition period. For instance, Muslims did not only contest Parliamentary elections in 1991 but also demanded that they be given 10% reservation in educational institutions and government services. In this sense, administrative policies specifically designed for the welfare and development of society might contradict those policies and programs dealing with the specific issues -

Gangotri Travel Guide - Page 1

Gangotri Travel Guide - http://www.ixigo.com/travel-guide/gangotri page 1 Jul Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, Gangotri When To umbrella. Max: Min: Rain: 617.5mm 31.10000038 23.60000038 A Hindu pilgrimage town in 1469727°C 1469727°C Uttarkashi district in the state of VISIT Aug Uttarakhand, Gangotri is situated http://www.ixigo.com/weather-in-gangotri-lp-1010734 Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, on the banks of river Bhagirathi. umbrella. Deeply associated with Goddess Max: Min: Rain: Jan 30.39999961 23.10000038 613.700012207031 8530273°C 1469727°C 2mm Ganga and Lord Shiva, the town is Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. part of the Char Dham. Max: Min: Rain: Sep 20.20000076 6.800000190 43.5999984741210 Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, 2939453°C 734863°C 94mm umbrella. Feb Max: Min: Rain: 30.29999923 21.29999923 242.300003051757 Famous For : Places To VisitReligiousCit Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen, 7060547°C 7060547°C 8mm umbrella. Max: Min: Rain: Oct It is associated with an intriguing 22.79999923 9.399999618 56.2999992370605 Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. 7060547°C 530273°C 5mm mythological legend, where Goddess Ganga, Max: Min: Rain: the daughter of heaven, manifested herself Mar 29.10000038 16.60000038 41.4000015258789 1469727°C 1469727°C 06mm in the form of a river to acquit the sins of Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. King Bhagiratha's predecessors. Following Max: Min: Rain: Nov 27.39999961 13.10000038 44.4000015258789 Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. which, Lord Shiva received her into his 8530273°C 1469727°C 06mm Max: Min: Rain: matted locks to minimise the immense Apr 25.79999923 11.69999980 6.30000019073486 7060547°C 9265137°C 3mm impact of her fall. -

Rights-Based Approaches the Links Between Human Rights and Biodiversity and Natural Resource Conservation Are Many and Complex

Rights-based approaches The links between human rights and biodiversity and natural resource conservation are many and complex. The conservation community is being challenged to take stronger measures to respect human rights and is taking opportunities to further their realisation. ‘Rights-based approaches’ (RBAs) to conservation are a promising way forward, but also raise a myriad of new challenges and questions, including what such approaches are, when and how they can be put into practice, and what their implications are for conservation. This volume gives an overview of key issues and questions in RBA. Rights-based approaches Rights and social justice related policies of major international organisations are reviewed. Case studies and position papers describe RBAs in a variety of contexts - protected areas, natural Exploring issues and opportunities for conservation resource management, access and bene t-sharing regimes, and proposed reduced emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD) mechanisms. No one blueprint for RBA emerges. However, there are common themes: supporting conservation for Exploring issues and opportunities both procedural and substantive rights, linking rights and responsibilities, equalising power relations, providing capacity building for rights holders and duty bearers, and recognising and engaging with local leaders and local people. RBAs can support improved governance but are, in turn, shaped by the governance systems in which they operate, as well as by history, politics, socio-economics and culture. Experience and dialogue will add to a fuller understanding of the promises and challenges of RBAs to conservation. The aim of this volume is to contribute to that discussion. Campese, Campese, by Edited et al. -

European Bulletin of Himalayan Research (EBHR)

EUROPEAN BULLETIN OF HIMALA Y AN RESEARCH Number 7 1994 CONTENTS EDITORIAL REVIEW ARTICLE Nepali Dictionaries - A New Contribution: Michael Hutl .............. BOOK REVIEW Wolf Donncr: Lebensraum Nepal. Eine Enrwicklungsgeographie. Hamburg: Institut fUr Asienkunde. 1994. Joanna Pfaff-Czamccka ...... 5 TOPICAL REPORTS Lesser-Known Languages in Nepal. A brief state-of-the-art report: Gerd Hansson ..................................... .. .....8 Deforestation in the Nepal Himalaya: Causes, Scope. Consequences: Dietrich Schmidt-Vogt .... ............................... 18 NepaJi Migration 10 Bhutan: Chrislopher Strawn .............. , .....25 Impact Monitoring of a Small Hydel Project in the Solu-Khumbu District Nepal: Susanne Wymann/Cordula Ou ....................36 INTERVIEWS .. 1 feel that I am here on a Mission ... : An Interview with the Vice-Chancellor of Tribhuvan UniversityINepal. Mr. Kedar Bhakta Mathema: Brigiue Merz .......... .. .............................. .42 NEWS Himalayan Ponraits: Thoughts and Opinions from the Film flimalaya Film Festival 18-20 Feb. 1994 in Kathmandu/Nepal: Brigille Merz .... .48 Oral Tradition Study Group/HimaJaya: Second Meeting in Paris. February 25. 1994 .. ......... ............................52 Nepal Maithili Samaj: A Good Beginning: Murari M. Thakur ............52 The Founeenth Annual Conference of the Linguistic Society of Nepal: November 26-27. 1993 ....................................55 CONTRIBUTORS TO THIS ISSUE .......... .... .... ........58 SUBSCRIPTION FORM NOTES TO CONTRIBUTORS REVIEW ARTICLE EDITORIAL Nepali Dictionaries - A New Contribution Mithael Hutt The first subscription "roundM ends with this issue, so we ask our readers 10 renew it (again for four issues 10 be published over the next two years), and A Practical Dictionary of Modern N~paJi, Editor·in-chief Ruth Laila possibly extend the circle of subscribers. Fonns are included al the end of the Schmidt, Co-editor Ballabh Mani Dahal. Delhi, Ratna Sagar, 1993. -

India Disaster Report 2013

INDIA DISASTER REPORT 2013 COMPILED BY: Dr. Satendra Dr. K. J. Anandha Kumar Maj. Gen. Dr. V. K. Naik, KC, AVSM National Institute of Disaster Management 2014 i INDIA DISASTER REPORT 2013 ii PREFACE Research and Documentation in the field of disaster management is one of the main responsibilities of the National Institute of Disaster Management as entrusted by the Disaster Management Act of 2005. Probably with the inevitable climate change, ongoing industrial development, and other anthropogenic activities, the frequency of disasters has also shown an upward trend. It is imperative that these disasters and the areas impacted by these disasters are documented in order to analyze and draw lessons to enhance preparedness for future. A data bank of disasters is fundamental to all the capacity building initiatives for efficient disaster management. In the backdrop of this important requirement, the NIDM commenced publication of India Disaster Report from the year 2011. The India Disaster Report 2013 documents the major disasters of the year with focus on the Uttarakhand Flash Floods and the Cyclone Phailin. Other disasters like building collapse and stampede have also been covered besides the biological disaster (Japanese Encephalitis). The lessons learnt in these disasters provide us a bench-mark for further refining our approach to disaster management with an aim at creating a disaster resilient India. A review of the disasters during the year reinforce the need for sustainable development as also the significance of the need for mainstreaming of disaster risk reduction in all developmental activities. We are thankful to all the members of the NIDM who have contributed towards this effort. -

Initial Environmental Examination IND:Uttarakhand Emergency

Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 47229-001 December 2014 IND: Uttarakhand Emergency Assistance Project Submitted by Uttarakhand Emergency Assistance Project (Roads & Bridges), Government of Uttarakhand, Dehardun This report has been submitted to ADB by the Program Implementation Unit, Uttarkhand Emergency Assistance Project (R&B), Government of Uttarakhand, Dehradun and is made publicly available in accordance with ADB’s public communications policy (2011). It does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB. Initial Environmental Examination July 2014 India: Uttarakhand Emergency Assistance Project Restoration Work of Kuwa-Kafnaul Rahdi Motor Road (Package No: UEAP/ PWD/ C14) Prepared by State Disaster Management Authority, Government of Uttarakhand, for the Asian Development Bank. i ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank ASI - Archaeological Survey of India BOQ - Bill of Quantity CTE - Consent to Establish CTO - Consent to Operate DFO - Divisional Forest Officer DSC - Design and Supervision Consultancy DOT - Department of Tourism CPCB - Central Pollution Control Board EA - Executing Agency EAC - Expert Appraisal Committee EARF - Environment Assessment and Review Framework EC - Environmental Clearance EIA - Environmental Impact Assessment EMMP - Environment Management and Monitoring Plan EMP - Environment Management Plan GoI - Government of India GRM - Grievance Redressal Mechanism IA - Implementing Agency IEE - Initial Environmental Examination IST - Indian Standard Time LPG - Liquid Petroleum Gas MDR - Major District -

UTTARAKASHI.Pdf

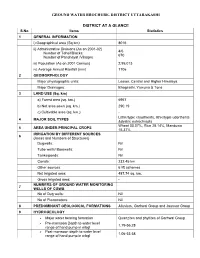

GROUND WATER BROCHURE, DISTRICT UTTARAKASHI DISTRICT AT A GLANCE S.No Items Statistics 1 GENERAL INFORMATION i) Geographical area (Sq km) 8016 ii) Administrative Divisions (As on 2001-02) 4/6 Number of Tehsil/Blocks: 670 Number of Panchayat /Villages iii) Population (As on 2001 Census) 2,95,013 iv) Average Annual Rainfall (mm) 1706 2 GEOMORPHOLOGY Major physiographic units: Lesser, Central and Higher Himalaya. Major Drainages: Bhagirathi, Yamuna & Tons 3 LAND USE (Sq. km) a) Forest area (sq. km.) 6957 b) Net area sown (sq. km.) 290.19 c) Cultivable area (sq. km.) - Lithic/typic cryorthents, lithic/typic udorthents 4 MAJOR SOIL TYPES &dystric eutrochrepts Wheat 33.07%, Rice 28.14%, Manduwa 5 AREA UNDER PRINCIPAL CROPS 15.37% IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES 6 (Areas and Numbers of Structures) Dugwells: Nil Tube wells/ Borewells: Nil Tanks/ponds: Nil Canals: 232.45 km Other sources: 6 lift schemes Net irrigated area: 487.74 sq. km. Gross irrigated area: - NUMBERS OF GROUND WATER MONITORING 7 WELLS OF CGWB No of Dug wells: Nil No of Piezometers: Nil 8 PREDOMINANT GEOLOGICAL FORMATIONS Alluvium, Garhwal Group and Jaunsar Group 9 HYDROGEOLOGY Major water bearing formation Quartzites and phyllites of Garhwal Group Pre-monsoon Depth to water level 1.79-56.28 range of hand pump in mbgl Post-monsoon depth to water level 1.06-53.58 range of hand pump in mbgl Long term water level trend in - 10 yrs in m/yr. GROUND WATER EXPLORATION BY 10 CGWB No of wells drilled (EW, OW, PZ, SH Total) Nil Depth Range (m) - Discharge (liters per second) - Storativity (s) - Transmissivity (m2/day) - 11 GROUND WATER QUALITY Parameters well within permissible limits. -

Shivling Trek in Garhwal Himalaya 2015

Shivling Trek in Garhwal Himalaya 2015 Area: Garhwal Himalayas Duration: 13 Days Altitude: 5263 mts/17263 ft Grade: Moderate – Challenging Season: May - June & Aug end – early Oct Day 01: Delhi – Haridwar (By AC Train) - Rishikesh (25 kms/45 mins approx) In the morning take AC Train/Volvo Coach from Delhi to Haridwar at 06:50 hrs. Arrival at Haridwar by 11:25 hrs, meet our guide and transfer to Rishikesh by road. On arrival check in to hotel. Evening free to explore the area. Dinner and overnight stay at the hotel. Day 02: Rishikesh - Uttarkashi (1150 mts/3772 ft) In the morning after breakfast drive to Uttarkashi via Chamba. One can see a panoramic view of the high mountain peaks of Garhwal. Upon arrival at Uttarkashi check in to hotel. Evening free to explore the surroundings. Dinner and overnight stay at the hotel. Day 03: Uttarkashi - Gangotri (3048 mts/9998 ft) In the morning drive to Gangotri via a beautiful Harsil valley. Enroute take a holy dip in hot sulphur springs at Gangnani. Upon arrival at Gangotri check in to hotel. Evening free to explore the beautiful surroundings. Dinner and overnight stay in hotel/TRH. Harsil: Harsil is a beautiful spot to see the colors of the nature. The walks, picnics and trek lead one to undiscovered stretches of green, grassy land. Harsil is a perfect place to relax and enjoy the surroundings. Sighting here includes the Wilson Cottage, built in 1864 and Sat Tal (seven Lakes). The adventurous tourists have the choice to set off on various treks that introduces them to beautiful meadows, waterfalls and valleys. -

S. R. Harnot's Cats Talk

S. R. Harnot’s Cats Talk S. R. Harnot’s Cats Talk Edited by Khem Raj Sharma and Meenakshi F. Paul S. R. Harnot’s Cats Talk Edited by Khem Raj Sharma and Meenakshi F. Paul This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by S. R. Harnot, Khem Raj Sharma, Meenakshi F. Paul and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-1357-2 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-1357-0 Dedicated to Elizabeth Paul CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Cats Talk ...................................................................................................... 9 Billiyan Batiyati Hain Translated by R. K. Shukla and Manjari Tiwari The Twenty-Foot Bapu Ji .......................................................................... 28 Bees Foot Ke Bapu Ji Translated by Meenakshi F. Paul and Khem Raj Sharma The Reddening Tree .................................................................................. 46 Lal Hota Darakht Translated by Meenakshi F. Paul Daarosh .....................................................................................................