Towards Sustainable Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gangotri Travel Guide - Page 1

Gangotri Travel Guide - http://www.ixigo.com/travel-guide/gangotri page 1 Jul Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, Gangotri When To umbrella. Max: Min: Rain: 617.5mm 31.10000038 23.60000038 A Hindu pilgrimage town in 1469727°C 1469727°C Uttarkashi district in the state of VISIT Aug Uttarakhand, Gangotri is situated http://www.ixigo.com/weather-in-gangotri-lp-1010734 Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, on the banks of river Bhagirathi. umbrella. Deeply associated with Goddess Max: Min: Rain: Jan 30.39999961 23.10000038 613.700012207031 8530273°C 1469727°C 2mm Ganga and Lord Shiva, the town is Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. part of the Char Dham. Max: Min: Rain: Sep 20.20000076 6.800000190 43.5999984741210 Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, 2939453°C 734863°C 94mm umbrella. Feb Max: Min: Rain: 30.29999923 21.29999923 242.300003051757 Famous For : Places To VisitReligiousCit Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen, 7060547°C 7060547°C 8mm umbrella. Max: Min: Rain: Oct It is associated with an intriguing 22.79999923 9.399999618 56.2999992370605 Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. 7060547°C 530273°C 5mm mythological legend, where Goddess Ganga, Max: Min: Rain: the daughter of heaven, manifested herself Mar 29.10000038 16.60000038 41.4000015258789 1469727°C 1469727°C 06mm in the form of a river to acquit the sins of Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. King Bhagiratha's predecessors. Following Max: Min: Rain: Nov 27.39999961 13.10000038 44.4000015258789 Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. which, Lord Shiva received her into his 8530273°C 1469727°C 06mm Max: Min: Rain: matted locks to minimise the immense Apr 25.79999923 11.69999980 6.30000019073486 7060547°C 9265137°C 3mm impact of her fall. -

In the Himalayas Interests, Conflicts, and Negotiations

Democratisation in the Himalayas Interests, Conflicts, and Negotiations Edited by Vibha Arora and N. Jayaram SI i ■ vv ■ vV"A' ■ •■ >•«tt •.■■>.. ■■>^1 ^ ^./v- >■ / t-'V 1^'' / o.,o,™n i8!i»- A Routledge India Original f\l Democratisation in the Himalayas Interests, Conflicts, and Negotiations Edited by Vibha Arora and N. Jayaram O Routledge Taylor & Francis Croup LONDON AND NEW YORK Contents List ofilhtstrations ix Notes on contributors x Preface xi Introduction: steering democratisation and negotiating identity in the Himalayas 1 VIBHA ARORA AND N. JAYARAM PARTI Shifting selves and competing identities 25 1 Seeking identities on the margins of democracy: Jad Bhotiyas of Uttarkashi 27 SUBHADR>\ MITRA CHANNA 2 The politics of census: fear of numbers and competing claims for representation in Naga society 54 DEBOJYOTI DAS 3 The making of the subaltern Lepcha and the Kalimpong stimulus 79 VIBHA ARORA PART II Negotiating democracy 115 4 Monks, elections, and foreign ti-avels: democracy and the monastic order in western Arimachal Pradesh, North-East India 117 SVVARGAIYOTl GOHAIN viii Contents 5 'Pure democracy' in 'new Nepal': conceptions, practices, and anxieties 135 AMANDA SNELLINGER PART III Territorial conflict and after 159 6 Demand for Kukiland and Kuki ethnic nationalism 161 VIBHA ARORA AND NGAMIAHAO KIPGEN 7 Displacement from Kashmir: gendered responses 186 CHARU SAWHNEY AND N1LIK.\ MEHROTR.\ Index 203 1 Seeking identities on the margins of democracy Jad Bhotiyas of Uttarkashi Subhpidm Mitra Chcimm The Indian democracy, unlike some others, for example, the French, has built itself upon the recognition of multiculturalism as well as protection ism towards those it considers marginal and weak. -

India Disaster Report 2013

INDIA DISASTER REPORT 2013 COMPILED BY: Dr. Satendra Dr. K. J. Anandha Kumar Maj. Gen. Dr. V. K. Naik, KC, AVSM National Institute of Disaster Management 2014 i INDIA DISASTER REPORT 2013 ii PREFACE Research and Documentation in the field of disaster management is one of the main responsibilities of the National Institute of Disaster Management as entrusted by the Disaster Management Act of 2005. Probably with the inevitable climate change, ongoing industrial development, and other anthropogenic activities, the frequency of disasters has also shown an upward trend. It is imperative that these disasters and the areas impacted by these disasters are documented in order to analyze and draw lessons to enhance preparedness for future. A data bank of disasters is fundamental to all the capacity building initiatives for efficient disaster management. In the backdrop of this important requirement, the NIDM commenced publication of India Disaster Report from the year 2011. The India Disaster Report 2013 documents the major disasters of the year with focus on the Uttarakhand Flash Floods and the Cyclone Phailin. Other disasters like building collapse and stampede have also been covered besides the biological disaster (Japanese Encephalitis). The lessons learnt in these disasters provide us a bench-mark for further refining our approach to disaster management with an aim at creating a disaster resilient India. A review of the disasters during the year reinforce the need for sustainable development as also the significance of the need for mainstreaming of disaster risk reduction in all developmental activities. We are thankful to all the members of the NIDM who have contributed towards this effort. -

Initial Environmental Examination IND:Uttarakhand Emergency

Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 47229-001 December 2014 IND: Uttarakhand Emergency Assistance Project Submitted by Uttarakhand Emergency Assistance Project (Roads & Bridges), Government of Uttarakhand, Dehardun This report has been submitted to ADB by the Program Implementation Unit, Uttarkhand Emergency Assistance Project (R&B), Government of Uttarakhand, Dehradun and is made publicly available in accordance with ADB’s public communications policy (2011). It does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB. Initial Environmental Examination July 2014 India: Uttarakhand Emergency Assistance Project Restoration Work of Kuwa-Kafnaul Rahdi Motor Road (Package No: UEAP/ PWD/ C14) Prepared by State Disaster Management Authority, Government of Uttarakhand, for the Asian Development Bank. i ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank ASI - Archaeological Survey of India BOQ - Bill of Quantity CTE - Consent to Establish CTO - Consent to Operate DFO - Divisional Forest Officer DSC - Design and Supervision Consultancy DOT - Department of Tourism CPCB - Central Pollution Control Board EA - Executing Agency EAC - Expert Appraisal Committee EARF - Environment Assessment and Review Framework EC - Environmental Clearance EIA - Environmental Impact Assessment EMMP - Environment Management and Monitoring Plan EMP - Environment Management Plan GoI - Government of India GRM - Grievance Redressal Mechanism IA - Implementing Agency IEE - Initial Environmental Examination IST - Indian Standard Time LPG - Liquid Petroleum Gas MDR - Major District -

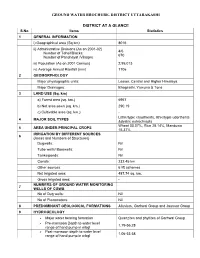

UTTARAKASHI.Pdf

GROUND WATER BROCHURE, DISTRICT UTTARAKASHI DISTRICT AT A GLANCE S.No Items Statistics 1 GENERAL INFORMATION i) Geographical area (Sq km) 8016 ii) Administrative Divisions (As on 2001-02) 4/6 Number of Tehsil/Blocks: 670 Number of Panchayat /Villages iii) Population (As on 2001 Census) 2,95,013 iv) Average Annual Rainfall (mm) 1706 2 GEOMORPHOLOGY Major physiographic units: Lesser, Central and Higher Himalaya. Major Drainages: Bhagirathi, Yamuna & Tons 3 LAND USE (Sq. km) a) Forest area (sq. km.) 6957 b) Net area sown (sq. km.) 290.19 c) Cultivable area (sq. km.) - Lithic/typic cryorthents, lithic/typic udorthents 4 MAJOR SOIL TYPES &dystric eutrochrepts Wheat 33.07%, Rice 28.14%, Manduwa 5 AREA UNDER PRINCIPAL CROPS 15.37% IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES 6 (Areas and Numbers of Structures) Dugwells: Nil Tube wells/ Borewells: Nil Tanks/ponds: Nil Canals: 232.45 km Other sources: 6 lift schemes Net irrigated area: 487.74 sq. km. Gross irrigated area: - NUMBERS OF GROUND WATER MONITORING 7 WELLS OF CGWB No of Dug wells: Nil No of Piezometers: Nil 8 PREDOMINANT GEOLOGICAL FORMATIONS Alluvium, Garhwal Group and Jaunsar Group 9 HYDROGEOLOGY Major water bearing formation Quartzites and phyllites of Garhwal Group Pre-monsoon Depth to water level 1.79-56.28 range of hand pump in mbgl Post-monsoon depth to water level 1.06-53.58 range of hand pump in mbgl Long term water level trend in - 10 yrs in m/yr. GROUND WATER EXPLORATION BY 10 CGWB No of wells drilled (EW, OW, PZ, SH Total) Nil Depth Range (m) - Discharge (liters per second) - Storativity (s) - Transmissivity (m2/day) - 11 GROUND WATER QUALITY Parameters well within permissible limits. -

Shivling Trek in Garhwal Himalaya 2015

Shivling Trek in Garhwal Himalaya 2015 Area: Garhwal Himalayas Duration: 13 Days Altitude: 5263 mts/17263 ft Grade: Moderate – Challenging Season: May - June & Aug end – early Oct Day 01: Delhi – Haridwar (By AC Train) - Rishikesh (25 kms/45 mins approx) In the morning take AC Train/Volvo Coach from Delhi to Haridwar at 06:50 hrs. Arrival at Haridwar by 11:25 hrs, meet our guide and transfer to Rishikesh by road. On arrival check in to hotel. Evening free to explore the area. Dinner and overnight stay at the hotel. Day 02: Rishikesh - Uttarkashi (1150 mts/3772 ft) In the morning after breakfast drive to Uttarkashi via Chamba. One can see a panoramic view of the high mountain peaks of Garhwal. Upon arrival at Uttarkashi check in to hotel. Evening free to explore the surroundings. Dinner and overnight stay at the hotel. Day 03: Uttarkashi - Gangotri (3048 mts/9998 ft) In the morning drive to Gangotri via a beautiful Harsil valley. Enroute take a holy dip in hot sulphur springs at Gangnani. Upon arrival at Gangotri check in to hotel. Evening free to explore the beautiful surroundings. Dinner and overnight stay in hotel/TRH. Harsil: Harsil is a beautiful spot to see the colors of the nature. The walks, picnics and trek lead one to undiscovered stretches of green, grassy land. Harsil is a perfect place to relax and enjoy the surroundings. Sighting here includes the Wilson Cottage, built in 1864 and Sat Tal (seven Lakes). The adventurous tourists have the choice to set off on various treks that introduces them to beautiful meadows, waterfalls and valleys. -

TOUR NO. 04 RISHIKESH – YAMUNOTRI – GANGOTRI – KEDARNATH – BADRINATH-RISHIKESH 2021 Duration: 10 - Days & 10 - Nights Transport: by 2X2 (27 Seater) Non A.C

TOUR NO. 04 RISHIKESH – YAMUNOTRI – GANGOTRI – KEDARNATH – BADRINATH-RISHIKESH 2021 Duration: 10 - Days & 10 - Nights Transport: By 2x2 (27 Seater) Non A.C. Bus Frequency: Every – Wednesday & Saturday Reporting Place: Bharat Bhoomi Tourist Complex, Shail Vihar, Rishikesh Tel: 0135-2433002 Reporting Time: One day before departure (Prenight Tuesday /Friday accommodation is included) Meals: Own Payment Basis Charges Per Seat Adult Child Sr Citizen May To Jun 24335 23475 23045 July To Nov 18325 17680 17360 Station / Remarks: - Activities/Approx. temp. (In Celsius) and Night halt Period Alt. in Mtrs) Dep/Arr. Time places 1st Day Rishikesh Dep 06.00:AM After morning tea, breakfast Enroute 226 Km by Bus Barkot Arr 01.00:PM Lunch Break Wednesday & Barkot Dep 02.00:PM Saturday Phoolchatti (2450) Arr 04.00:P-M Dinner & Night Halt. Temp Min: 10 Temp Max: 25 2nd Day Phoolchatti Dep 06.00:AM Breakfast at TRH Jankichatti 08 Km Drive & 10 Yamunotri Arr 10:00:AM Visit Yumnotri Holi Dip, Pooja Darshan & Lunch Break km trek (to & fro) Yamunotri Dep 11:00:PM Thursday & Sunday Phoolchatti (2450) Arr 04.30:PM Dinner & Night Halt. Temp Min: 10 Temp Max: 25 3rd Day 200Km Phoolchatti Dep 06.00:AM After Tea / Breakfast at TRH Barkot by Bus Friday & Uttarkashi Arr 01.00:PM Lunch at TRH Uttarkashi Monday Uttarkashi Dep 02.00:PM Visit Vishwanath Temple & lunch halt Harsil (2620) Arr 05.30:PM Dinner & Night Halt. Temp Min: 10 Temp Max: 22 4th Day Harsil Dep 06:00A.M. After Tea / Breakfast at TRH Gangotri. 125 Km by Bus Gangotri Arr 09:30A.M. -

HAPL-Chardham-Yatra-By-Helicopter-(A).Pdf

HERITAGE AVIATION Heritage Aviation Private Limited is approved by Director General Civil Aviation, (DGCA) and Ministry of Civil Aviation, Government of India to operate aircraft and helicopter services. We operate luxury private aircrafts and helicopters for leisure & pilgrimage tours, business travel and corporate travel. Our helicopter services have a wide variety of options for you to choose from and make your travel a luxurious and comfortable experience. We specialize in helicopter services for CHARDHAM Yatra from Dehradun. Char Dham Yatra is pilgrim of four devotional Dham Yamnotri – Gangotri – Kedarnath and Badrinath. We make sure that passengers not only get luxurious helicopter ride but we also ensure that they would be having equally Quick, Comfortable and pleasing darshans at all temples along with the local sightseeing. * CHARDHAM YATRA IN 4 NIGHTS/ 5 DAYS * Yatra starts from the capital of Uttarakhand, the queen of the hills, Dehradun. These four different pilgrim destinations, the Char Dhams, situated in the magical Himalayas, joined by mysticism and spirituality, beckon millions of visitors every year for a voyage into the unknown, for a flight towards the heavens, for a journey into the self… “Auspicious Holy Yatra” HERITAGE AVIATION *OUR PACKAGE INCLUDES* Helicopter trip starts from Dehradun. Complimentary stay, pickup and Airport transfer for 1 Night in Haridwar/ Dehradun. Includes stay & meals for 4 Nights / 5 Days. All local transport and sightseeing by Toyota Innova. VIP Darshan at all Four temples i.e. Yamunotri, Gangotri, Kedarnath and Badrinath. Exclusive Maha Abhishek Puja at Badrinath. Palki at Yamunotri. 2 HERITAGE AVIATION *DAY WISE ITINERARY * DAY 1 DAY 1 DEHRADUN TO YAMUNOTRI 0700 AM DEPARTURE S’DHARA HELIPAD , DEHRADUN 0745 AM ARRIVAL KHARSALI HELIPAD, YAMUNOTRI Passengers are requested to reach state government helipad on Sahastradhara Road, Dehradun which is the starting and ending point of this yatra. -

Uttarkashi.Pdf

on 3 in Uttarkashi District, Uttarakhand August 2012 along Bhagirathi Valley rd A Study on Flash Floods and Landslides Disaster A Study on Flash Floods and Landslides Disaster on 3rd August 2012 along Bhagirathi Valley in Uttarkashi District, Uttarakhand Surya Parkash World Centre of Excellence on Landslide Disaster Reduction ISBN 978-93-82571-10-0 National Institute of Disaster Management World Centre of Excellence on Landslide Disaster Reduction Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt. of India National Institute of Disaster Management 5 B, I.P. Estate, Ring Road, New Delhi – 110 002 9 7 8 9 3 8 2 5 7 1 1 0 0 Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt. of India www.nidm.gov.in 5 B, I.P. Estate, Ring Road, New Delhi – 110 002 www.nidm.gov.in A Study on Flash Floods and Landslides Disaster on 3rd August 2012 along Bhagirathi Valley in Uttarkashi District, Uttarakhand by Surya Parkash, Ph.D. World Centre of Excellence on Landslide Disaster Reduction National Institute of Disaster Management Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt. of India 5 B, I.P. Estate, Ring Road, New Delhi – 110 002 www.nidm.gov.in A Study on Flash Floods and Landslides Disaster on 3rd August 2012 along Bhagirathi Valley in Uttarkashi District, Uttarakhand Report Prepared and Submitted by Dr. Surya Parkash to NIDM, New Delhi during August 2012 ISBN 978-93-82571-10-0 © NIDM, New Delhi Edition : First, 2015 Published by National Institute of Disaster Management (NIDM), Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, New Delhi - 110 002, India Citation Parkash Surya (2015). A Study on Flash Floods and Landslides Disaster on 3rd August 2012 along Bhagirathi Valley in Uttarkashi District, Uttarakhand, National Institute of Disaster Management, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, New Delhi - 110 002, 230 Pages Disclaimer This document may be freely reviewed, reproduced or translated, in part or whole, purely on non-profit basis for humanitarian, social and environmental well-being, We welcome receiving information and suggestions on its adaptation or use in actual training situations. -

Chardham Yatra 2020 by Leisure Hotels Leisure Hotels Group

Chardham Yatra 2020 By Leisure Hotels Leisure Hotels Group • A 30-year-old group, prominent in Northern India and largest in the state of Uttarakhand • 27 properties, 20 locations, 5 states • 850+ rooms & 1000+ employees • Coming up in Hostel segment in Rishikesh • Smart Business Hotels, Boutique Resorts, Bespoke Villas and Luxury Camps Char Dham Yatra INTRODUCTION Chardham Yatra is one of the most sacred Hindu Pilgrimage consisting of four shrines named as Gangotri, Yamunotri, Kedarnath and Badrinath in Uttarakhand. It is believed that the Char Dham Yatra opens the gates of salvation by washing away all the sins of mankind. It is also believed that this journey must be undertaken at least once in a lifetime to achieve “moksh”. “Let Leisure Hotels take care of you right from your doorstep to the darshans and back” YAMUNOTRI The first dham en route the yatra, is situated at Yamunotri – where the scared river Yamuna originates. It is named after Goddess Yamuna, the twin sister of Yama (the goddess of death). A bath in the holy waters of Yamuna River is said to cleanse one of the all sins and protects from untimely death. The temple houses a black marble idol of the goddess. GANGOTRI Is the birthplace of the holy river Ganga. According to the popular Hindu legend, it was here that Goddess Ganga descended when Lord Shiva released the mighty river from the locks of his hair. Dedicated to the goddess, Gangotri Dham is the second temple that falls on the Chota Char dham route. It was built by the Nepalese General, Amar Singh Thapa. -

Bored in Bihar 235 India's Coral Strand 240 Easy Like Water 244

vi | Contents PART THREE: DELTA Bored in Bihar 235 Holi on the Hooghly 275 India’s Coral Strand 240 The World of Apu 278 Easy Like Water 244 The Aging Prostitute 281 The Impossible City 247 A Walk in the Park 286 Where You Are From? 251 Going Native 291 Women of the Delta 255 Last Jewel in the Crown 298 The Will of Allah 260 Packed and Pestilential 303 Fields of Salt 264 Multiple Personalities 305 The Tiger of Chandpai 269 The Bollywood Goddess 310 On the Beach 274 The Coin Collector 315 -1— 0— +1— 053-73297_ch00_1aP.indd 6 01/03/18 10:06 PM 10. BIG FISH STORY hat was a well- bred En glishman in the colonies without his rod and gun? One missed the weekend shooting parties at one’s country home, the ghillies and beaters on the grouse Wmoors of Scotland, the stag at bay, the rivers alive with brown trout and sil- very salmon. But India offered its own alternatives. The first tourists to fol- low in the footsteps of Captains Hodgson and Herbert after they reached the source of the Ganges rejoiced in the abundance of wild game. “Our party con- sisted of three Eu ro pean gentlemen, each taking ten servants, while our cool- ees, or porters, amounted to eighty at the least,” wrote Lieutenant George Francis White of the Ninety- First Regiment in an account of his travels pub- lished in 1838. “Our sportsmen filled their game bags, after a very exhilarat- ing pursuit of the furred and feathered race, most beautiful to the eye.” Calling it sport was a stretch; it was more like wholesale slaughter. -

Variations in Morphological and Biochemical Characters of Seabuckthorn (Hippophae Salicifolia D

Tropical Agricultural Research & Extension 9, 2006 Variations in morphological and biochemical characters of Seabuckthorn (Hippophae salicifolia D. Don) populations growing in Harsil area of Garhwal Himalaya in India *V.K.Yadav, V.K. Sah, A.K. Singh and S.K. Sharma College of Forestry and Hill Agriculture, G.B. Pant University of Agriculture & Technology, Hill Campus, Ranichauri, Tehri Garhwal-249 199 (Uttaranchal) India Accepted 01st August, 2006 ABSTRACT The present investigation was carried out to study the variation in morphological and biochemical characters of different seabuckthorn (Hippophae salicifolia) populations growing naturally in and around Harsil and Gangotri area of Uttarkashi district of Uttaranchal, India. Plants showed varied morphology from shrub to tree, fruit shape from round to ovate and fruit colour from greenish-yellow to yellow-orange. Number of leaves per 10 cm running length of branch ranged from 10.83 to 29.83 and leaf area from 2.28 to 9.35 cm2. Weight of 100 fruits varied from 11.53 to 18.87g, number of fruits per 10 cm fruiting branch ranged from 10.69 to 99.40 and fruit yield of same length of branch from 1.34 to 15.98 g. Acidity in juice calculated as citric acid varied between 4.89 to 7.93 per cent and total soluble solids ranged between 6.93 to 10.0 ºB. Higher juice percentage was observed in this species as compared to H. rhamnoides and the range was between 70.70 to 79.23 per cent. Based on the study, it is concluded that wide variations exists in different populations of H.