CHAPTER FOUR Pointers to New Social Order Introduction This

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

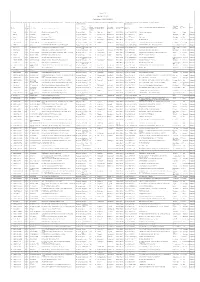

Janakeeya Hotel Updation 07.09.2020

LUNCH LUNCH LUNCH Home No. of Sl. Rural / No Of Parcel By Sponsored by District Name of the LSGD (CDS) Kitchen Name Kitchen Place Initiative Delivery units No. Urban Members Unit LSGI's (Sept 7th ) (Sept 7th ) (Sept 7th) Janakeeya 1 Alappuzha Ala JANATHA Near CSI church, Kodukulanji Rural 5 32 0 0 Hotel Coir Machine Manufacturing Janakeeya 2 Alappuzha Alappuzha North Ruchikoottu Janakiya Bhakshanasala Urban 4 194 0 15 Company Hotel Janakeeya 3 Alappuzha Alappuzha South Samrudhi janakeeya bhakshanashala Pazhaveedu Urban 5 137 220 0 Hotel Janakeeya 4 Alappuzha Ambalappuzha South Patheyam Amayida Rural 5 0 60 5 Hotel Janakeeya 5 Alappuzha Arattupuzha Hanna catering unit JMS hall,arattupuzha Rural 6 112 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 6 Alappuzha Arookutty Ruchi Kombanamuri Rural 5 63 12 10 Hotel Janakeeya 7 Alappuzha Bharanikavu Sasneham Janakeeya Hotel Koyickal chantha Rural 5 73 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 8 Alappuzha Budhanoor sampoorna mooshari parampil building Rural 5 10 0 0 Hotel chengannur market building Janakeeya 9 Alappuzha Chenganoor SRAMADANAM Urban 5 70 0 0 complex Hotel Chennam pallipuram Janakeeya 10 Alappuzha Chennam Pallippuram Friends Rural 3 0 55 0 panchayath Hotel Janakeeya 11 Alappuzha Cheppad Sreebhadra catering unit Choondupalaka junction Rural 3 63 0 0 Hotel Near GOLDEN PALACE Janakeeya 12 Alappuzha Cheriyanad DARSANA Rural 5 110 0 0 AUDITORIUM Hotel Janakeeya 13 Alappuzha Cherthala Municipality NULM canteen Cherthala Municipality Urban 5 90 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 14 Alappuzha Cherthala Municipality Santwanam Ward 10 Urban 5 212 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 15 Alappuzha Cherthala South Kashinandana Cherthala S Rural 10 18 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 16 Alappuzha Chingoli souhridam unit karthikappally l p school Rural 3 163 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 17 Alappuzha Chunakkara Vanitha Canteen Chunakkara Rural 3 0 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 18 Alappuzha Ezhupunna Neethipeedam Eramalloor Rural 8 0 0 4 Hotel Janakeeya 19 Alappuzha Harippad Swad A private Hotel's Kitchen Urban 4 0 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 20 Alappuzha Kainakary Sivakashi Near Panchayath Rural 5 0 0 0 Hotel 43 LUNCH LUNCH LUNCH Home No. -

Lions Clubs International Club Membership Register

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER SUMMARY THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF DECEMBER 2015 MEMBERSHI P CHANGES CLUB CLUB LAST MMR FCL YR TOTAL IDENT CLUB NAME DIST NBR COUNTRY STATUS RPT DATE OB NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERS 4193 026685 CALICUT INDIA 318 E 4 12-2015 104 5 1 0 -4 2 106 4193 026686 CANNANORE INDIA 318 E 4 12-2015 132 3 0 1 -12 -8 124 4193 026697 KANHANGAD INDIA 318 E 4 12-2015 89 0 0 0 -2 -2 87 4193 026699 KASARAGOD INDIA 318 E 4 12-2015 40 0 0 0 0 0 40 4193 026704 KUTHUPARAMBA INDIA 318 E 4 12-2015 69 10 0 0 -1 9 78 4193 026705 MANJESHWAR-UPPALA L C INDIA 318 E 4 12-2015 37 0 1 0 -9 -8 29 4193 026719 PAYYANUR INDIA 318 E 4 12-2015 82 13 0 0 -4 9 91 4193 026728 TALIPARAMBA INDIA 318 E 4 12-2015 77 0 0 0 0 0 77 4193 026729 TELLICHERRY INDIA 318 E 4 12-2015 92 15 0 0 -5 10 102 4193 028218 SULTANS BATTERY INDIA 318 E 4 11-2015 61 0 0 0 -1 -1 60 4193 036638 QUILANDY INDIA 318 E 4 12-2015 37 1 0 0 -4 -3 34 4193 037108 BADAGARA INDIA 318 E 4 12-2015 53 3 0 0 0 3 56 4193 039781 IRITTY INDIA 318 E 4 12-2015 48 7 0 0 0 7 55 4193 039782 KALPETTA INDIA 318 E 4 12-2015 25 0 0 0 0 0 25 4193 041807 PERAMBRA INDIA 318 E 4 11-2015 19 0 0 0 0 0 19 4193 044598 CANNANORE NORTH INDIA 318 E 4 12-2015 18 0 0 0 0 0 18 4193 045550 BALUSSERY INDIA 318 E 4 11-2015 32 0 0 0 0 0 32 4193 045629 PAYYOLI INDIA 318 E 4 12-2015 54 1 0 0 -2 -1 53 4193 046225 THAMARASERRY INDIA 318 E 4 12-2015 33 0 0 0 0 0 33 4193 047539 NADAPURAM INDIA 318 E 6 12-2015 21 0 0 0 -21 -21 0 4193 048571 CANNANORE SOUTH INDIA 318 E 4 -

Unclaimed September 2018

SL NO ACCOUNT HOLDER NAME ADDRESS LINE 1 ADDRESS LINE 2 CITY NAME 1 RAMACHANDRAN NAIR C S/O VAYYOKKIL KAKKUR KAKKUR KAKKUR 2 THE LIQUIDATOR S/O KOYILANDY AUTORIKSHA DRIVERS CO-OP SOCIE KOLLAM KOYILANDY KOYILANDY 3 ACHAYI P K D/OGEORGE P K PADANNA ARAYIDATH PALAM PUTHIYARA CALICUT 4 THAMU K S/O G.R.S.MAVOOR MAVOOR MAVOOR KOZHIKODE 5 PRAMOD O K S/OBALAKRISHNAN NAIR OZHAKKARI KANDY HOUSE THIRUVALLUR THIRUVALLUR KOZHIKODE 6 VANITHA PRABHA E S/O EDAKKOTH HOUSE PANTHEERANKAVU PANTHEERANKAVU PANTHEERAN 7 PRADEEPAN K K S/O KOTTAKKUNNUMMAL HOUSE MEPPAYUR MEPPAYUR KOZHIKODE 8 SHAMEER P S/O KALTHUKANDI CHELEMBRA PULLIPARAMBA MALAPPURAM 9 MOHAMMED KOYA K V S/O KATTILAVALAPPIL KEERADATHU PARAMBU KEERADATHU PARAMBU OTHERS 10 SALU AUGUSTINE S/O KULATHNGAL KOODATHAI BAZAR THAMARASSERY THAMARASSE 11 GIRIJA NAIR W/OKUNHIRAMAN NAIR KRISHADARSAN PONMERI PARAMBIL PONMERI PARAMBIL PONMERI PA 12 ANTSON MATHEW K S/O KANGIRATHINKAV HOUSE PERAMBRA PERUVANNAMUZHI PERUVANNAM 13 PRIYA S MANON S/O PUNNAMKANDY KOLLAM KOLLAM KOZHIKODE 14 SAJEESH K S/ORAJAN 9 9 KOTTAMPARA KURUVATTOOR KONOTT KURUVATTUR 15 GIRIJA NAIR W/OKUNHIRAMAN NAIR KRISHADARSAN PONMERI PARAMBIL PONMERI PARAMBIL PONMERI PA 16 RAJEEVAN M K S/OKANNAN MEETHALE KIZHEKKAYIL PERODE THUNERI PERODE 17 VINODKUMAR P K S/O SATHYABHAVAN CHEVAYOOR MARRIKKUNNU CHEVAYUR 18 CHANDRAN M K S/O KATHALLUR PUNNASSERY PUNNASSERY OTHERS 19 BALAKRISHNAN NAIR K S/O M.C.C.BANK LTD KALLAI ROAD KALLAI ROAD KALLAI ROA 20 NAJEEB P S/O ZUHARA MANZIL ERANHIPALAM ERANHIPALAM ERANHIPALA 21 PADMANABHAN T S/O KALLIKOODAM PARAMBA PERUMUGHAM -

Dictionary of Martyrs: India's Freedom Struggle

DICTIONARY OF MARTYRS INDIA’S FREEDOM STRUGGLE (1857-1947) Vol. 5 Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu & Kerala ii Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 5 DICTIONARY OF MARTYRSMARTYRS INDIA’S FREEDOM STRUGGLE (1857-1947) Vol. 5 Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu & Kerala General Editor Arvind P. Jamkhedkar Chairman, ICHR Executive Editor Rajaneesh Kumar Shukla Member Secretary, ICHR Research Consultant Amit Kumar Gupta Research and Editorial Team Ashfaque Ali Md. Naushad Ali Md. Shakeeb Athar Muhammad Niyas A. Published by MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVERNMENT OF IDNIA AND INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH iv Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 5 MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA and INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH First Edition 2018 Published by MINISTRY OF CULTURE Government of India and INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH 35, Ferozeshah Road, New Delhi - 110 001 © ICHR & Ministry of Culture, GoI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN 978-81-938176-1-2 Printed in India by MANAK PUBLICATIONS PVT. LTD B-7, Saraswati Complex, Subhash Chowk, Laxmi Nagar, New Delhi 110092 INDIA Phone: 22453894, 22042529 [email protected] State Co-ordinators and their Researchers Andhra Pradesh & Telangana Karnataka (Co-ordinator) (Co-ordinator) V. Ramakrishna B. Surendra Rao S.K. Aruni Research Assistants Research Assistants V. Ramakrishna Reddy A.B. Vaggar I. Sudarshan Rao Ravindranath B.Venkataiah Tamil Nadu Kerala (Co-ordinator) (Co-ordinator) N. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kozhikode Rural District from 15.07.2018 to 21.07.2018

Accused Persons arrested in Kozhikode Rural district from 15.07.2018 to 21.07.2018 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Cr. No. PARAPURATH 21-07-2018 2018/279 IPC Agesh K K . 19, CHELANNU BAILED BY 1 Fahad GAFOOR HOUSE. PALATH P at 21:40 & 185 MV Vatakara sub Inspector Male R POLICE O . PALLIPOYIL hrs ACT, U/s 21- of Polcie 07-2018 Cr. No. KULATHUPARAM 21-07-2018 2018/118(a) SADANAN 35, BIL HOUSE, THOTTILPAL BAILED BY 2 Subeesh at 22:35 of KP Act, Vatakara BIJU. R. C DAN Male AKKAL POST AM POLICE hrs U/s 21-07- KAVILUMPARA 2018 Cr. No. KAPPARAMBATH 21-07-2018 2018/118(a) HARIDASA 23, KUNNUMM BAILED BY 3 Abijith (HO), at 22:20 of KP Act, Vatakara SI Sunil.M N Male AKKARA POLICE ORKKATTERI hrs U/s 21-07- 2018 Cr. No. PULIYULLATHIL 21-07-2018 2018/118(a) BALAKRISH 35, KUNNUMM BAILED BY 4 Praveen (HO), at 22:20 of KP Act, Vatakara SI Sunil.M NAN Male AKKARA POLICE ORKKATTERI hrs U/s 21-07- 2018 Cr. No. NEAR GOV KUNIYAPARAMB 21-07-2018 2018/118(a) 24, HOSPITAL BAILED BY 5 Shibin NANU ATH HO, at 21:25 of KP Act, Vatakara SI Sunil.M Male ORKKATTER POLICE ORKKATTERI hrs U/s 21-07- I 2018 Cr. -

Old Age Pension (60-79Yrs)

OLD AGE PENSION LIFE INCOME LESS ABOVE 60 CERTIFICATE SL. NO. BENEFICIARY NAME S/o, D/o, W/o ADDRESS THAN 4000? YEARS? SUBMITTED OR NOT? 1 B. SITAMMA W/o B. APPA RAO R/o MANGLUTAN YES YES YES 2 B. APPA RAO S/o LATE EARRAIAH R/o MANGULTAN YES YES YES 3 TULSI RAJAN MRIDHA S/o LATE AKHAY KR. MRIDHA R/o BILLIGROUND YES YES YES 4 KALIDAS HALDER S/o LATE BHARAT HALDER R/o BILLYGROUND YES YES YES 5 BELA RANI BARAL W/o RAM KRISHNA BARRAL R/o BILLIGROUND YES YES YES 6 RASIK CHANDRA DEVNATH S/o LATE R C DEVNATH R/o BILLIGROUND YES YES YES 7 SHANTI HALDER W/o MANIDRA HALDER R/o BILLY GROUND YES YES YES 8 SAROJINI BEPARI W/o R K BEPARI R/o SWADESH NAGAR YES YES YES 9 SARALA GAIN W/o SURYA GAIN R/o GOVINDAPUR YES YES YES 10 PANCHALI RANI TIKADER W/o G CTIKADER R/o NIMBUDERA YES YES YES 11 RAM KRISHNA BEPARI S/o B BEPARI R/o SWADESH NAGAR YES YES YES 12 SIDHIRSWAR BAROI S/o UMBIKACHAND BAROI R/o HARI NAGAR YES YES YES 13 MATI BAROI W/o SIDHIRSWAR BAROI R/o HARI NAGAR YES YES YES 14 UMESH CH. MONDAL S/o GIRISH CH. MONDAL R/o NIMBUDERA YES YES YES 15 ANIL KRISHNA DAS S/o LATE NAREN DAS R/o HARINAGAR YES YES YES 16 PROBHAT DAS S/o LATE BUDDHIMANTA DAS R/o PINAKINAGAR YES YES YES 17 NIROLA BISWAS W/o MANINDRA NATH BISWAS R/o HARINAGAR YES YES YES 18 JAGATRAM KUJUR S/o GEORGE KUJUR R/o LAUKINALLAH YES YES YES 19 KESHAB CHANDRA ADHIKARY S/o B CH ADHIKARY R/o JAIPUR YES YES YES 20 P. -

Unpaid Dividend-17-18-I3 (PDF)

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L72200KA1999PLC025564 Prefill Company/Bank Name MINDTREE LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 17-JUL-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 696104.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) 49/2 4TH CROSS 5TH BLOCK MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANAND NA KORAMANGALA BANGALORE INDIA Karnataka 560095 54.00 23-May-2025 2539 unpaid dividend KARNATAKA 69 I FLOOR SANJEEVAPPA LAYOUT MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANTONY FELIX NA MEG COLONY JAIBHARATH NAGAR INDIA Karnataka 560033 72.00 23-May-2025 2646 unpaid dividend BANGALORE ROOM NO 6 G 15 M L CAMP 12044700-01567454- Amount for unclaimed and A ARUNCHETTIYAR AKCHETTIYAR INDIA Maharashtra 400019 10.00 23-May-2025 MATUNGA MUMBAI MI00 unpaid -

Form 19 a (See Rule 24 A(3)) Certified List ( GROUP B- PART-I) It

Form 19 A (See Rule 24 A(3)) Certified List ( GROUP B- PART-I) It is certified that the persons whose names are appering in this list are tested as positve as on 12/12/2020 15:32:10 (Date & Time) for covid 19 infection by the Government Hospital/Lab recognized by the Government OR are under quarantine due to COVID 19 ELECTION DETAILS ID CARD DETAILS Gender GP/ Municpality / Name of Ward Sl Municipal / Ward Name of Block Name of Dist Electoral roll Part Name of Address of the present location of hospitalisation/ quarantine Grama Taluk District Name Age Father/ Husband Address for communication with Pincode District GP/Municipal / No No No /M / F Corporation No Divsion & No Divsion & No no Sl no ID card panchayath Corporation /T serial No 1 Amina 61 M S/o W/o Saidali Chorath Valappil thalamunda, 679576 Malappuram Edapal G94 9 Thuyyam/9 Edappal/12 Pt.No2 SlNo563 Election KL/06/038/534095 Chorath Valappil thalamunda Edapal 9 Ponnani Malappuram Id 2 Rasheed 38 M S/o Saidalavi Palliyalil, 676108 Malappuram Triprangode G88 9 Chamravattom/10 Thirunavaya/16 Pt.No1 SlNo205 Election FMJ1817931 Palliyalil Triprangode 9 Tirur Malappuram Id 3 Shahid 28 M S/o Hidayathulla Padinjarakath, 676108 Malappuram Triprangode G88 18 Alathiyur/9 Thirunavaya/16 Pt.No1 SlNo888 Election YEU0460931 Padinjarakath Triprangode 18 Tirur Malappuram Id 4 abilash 26 M S/o rajagobalan EDATHARATHODI, 679357 Malappuram Aliparamba G43 18 Kunnakkavu/10 Elamkulam/6 Pt.No2 SlNo181 Election fqj3647963 EDATHARATHODI Aliparamba 18 PerinthalmannaMalappuram Id 5 ANJU CHALARI 27 F S/o RAVEENDRAN CHALARI KANNAMVETTIKKAVU, 673637 Malappuram Cherukavu G08 4 Puthukkode/17 Vazhakkad/28 Pt.No1 SlNo61 Election ZXU0350728 CHALARI KANNAMVETTIKAVU CHERAPADAM Cherukavu 4 Kondotty Malappuram Id 6 FAISAL K 38 M S/o koya KARIMBANAKKAL,NAITHALLOOR,PONNANI, 679584 Malappuram Ponnani Wards 1 M42 12 / / Pt.No02 SlNo835 Election SECIDCB81A85C KARIMBANAKKAL,NAITHALLOOR,PONNANI Ponnani Wards 1 12 Ponnani Malappuram to 26 Id to 26 7 Hafeefa. -

Ali Musliyar Scholar Turned Freedom Fighter-Malabar Pages

ALI MUSLIYAR SCHOLAR TURNED FREEDOM FIGHTER-MALABAR PAGES Hussain Randathani 1 In Malabar, on the coast of Arabian sea in South India, Musliyar is a familiar epithet to the Islamic scholars. The word owes it s origin to Arabic and Tamil, a south Indian language- Muslih an Arabic term meaning, one who refine and yar a honorific title used in the area. The word was coined by the Makhdums as a degree to those who completed their studies in the Ponnani mosque Academy and later it came to be used to all those who performed religious duties. The Musliyars, hither to remained as religious heads turned into politics during colonial period starting from 1498 with the coming o the Portuguese on the coast. Muslims, as a trading community had become influential in the area through their trade and naval fights against the colonial invaders. Islam is said to had reached on the coast during the time of the prophet Muhammad, ie., in the seventh century, and prospered through trade and conversion making the land a house of Islam (Dar al Islam). The local rulers provided facilities to the Muslim sufi missionaries accompanying the traders, to prosper themselves and the presence of Islam naturally did away with caste restrictions which had been the oar of discrimination in Malabar society. Ali Musliyar (1854-1922), as told above, belonged to the family of scholars of Malabar, residing at the present Nellikkuthu, 8 Kilometer away on Manjeri Mannarkkad Road in the district of Malappuram, in South India. The Place is a Muslim dominated area, people engaging mainly in agriculture and petty trades. -

Social Exclusion of Ravuthar Community: a Case Study

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 ResearchGate Impact Factor (2018): 0.28 | SJIF (2018): 7.426 Social Exclusion of Ravuthar Community: A Case Study Mohammed Rishad K P M.Phil Scholar, Gandhigram Rural Institute (Deemed to be University) Centre for Applied research Dindigul, Tamil Nadu, India Abstract: India, the world’s largest democracy, has a multi-cultural rash that has numerous religious communities. According to the 2011 census, 79.8 percent are practicing Hinduism and 14.2 percent are adheres to Islam, while the remaining 6 percent are other religions. According to Rizvi and Roy (1984), Indian Muslims are not a homogeneous community as it appears in the general perception Muslims are divided based on different religious ideologies, caste differentiation and customary practices. Among the different Muslim communities, Ravuthar is one of the Muslim communities from the South Indian States of Tamil Nadu and Kerala who are socially excluded at a wider. The etymology of the word suggests ‘ravath’ means ‘warriors’. But in reality, the Ravuthar community is facing high discrimination among the Muslim community. The present study is focused on how the Ravuthar community is excluded or discriminated among the Muslim community at Thiruvegappura Panchayat, Palakkad District, and Kerala by using descriptive research design. The researcher has employed an interview guide and case study. From the case studies, the relevant information was collected by the researcher. In the community, they were facing various issues such as stigma discrimination based on their linguistic and spatial. Their representation in any religious or social positions is very less. -

2020030324.Pdf

郸觀 郸GOVT. OF INDIA NDIA 郸 LAKSHADWEEP ADMINISTRATION ͬI郸 I郸 郸(Secretariat – Service Section) I⟦A DIA /^^^Kavaratti Island – 682 555 Change Request Form Recruitment 2019 - 2020 Name:___________________________________________________________ DOB:_______________Contact No.______________________________ Address:_________________________________________________________ Post (as Roll No. (as Changes to be made applicable) applicable) U- UD Clerk Stenogr S- apher L- LD Clerk Multi Skilled M- Employee (MSE) Signature of the applicant Email: [email protected] Details of applicants who have applied for the post of UDC vide F.No.12/45/2019-Services\3160 dated 21.10.2019 and F.No.12/33/2019-Services/384 dated 10.02.2020 Sl. No. Roll No. Name Father/Mother Name Date of Age Comm Permanent Address Address For Native Exam Remar Birth unity Communication Center ks 1 U-153 Abdul Ameer Babu.U Hamza.C 13/01/1986 33 ST Uppathoda, Agatti Uppathoda, Agatti Agatti Kochi 2 U-1603 Abdul Bari.PP Kidave.TK (Late) 08/12/1984 34 ST Pulippura House, Agathi. Pulippura House, Agatti Agatti Agathi. 3 U-1013 Abdul Gafoor.P.K Koyassan.K.C 16/03/1987 32 ST Punnakkod House, Agathi. Punnakkod House, Agatti Agatti Agathi. 4 U-810 Abdul Gafoor.TP Ummer koya.p 28/11/1986 32 ST Thekku Puthiya LDC General Section Agatti Kavarat [Govt. illam,Agatti Kavaratti ti Ser] 5 U-1209 Abdul hakeem.K Kasmikoya.P 02/08/1991 28 ST Keepattu Agatti Keepattu Agatti Agatti Agatti 6 U-821 Abdul Hakeem.M.M Abdul Naser.P 04/08/1992 27 ST Mubarak Manzil (H), Agatti Mubarak Manzil (H), Agatti Kavarat [Govt. -

Ahtl-European STRUGGLE by the MAPPILAS of MALABAR 1498-1921 AD

AHTl-EUROPEAn STRUGGLE BY THE MAPPILAS OF MALABAR 1498-1921 AD THESIS SUBMITTED FDR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE DF Sactnr of pitilnsopliQ IN HISTORY BY Supervisor Co-supervisor PROF. TARIQ AHMAD DR. KUNHALI V. Centre of Advanced Study Professor Department of History Department of History Aligarh Muslim University University of Calicut Al.garh (INDIA) Kerala (INDIA) T6479 VEVICATEV TO MY FAMILY CONTENTS SUPERVISORS' CERTIFICATE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT LIST OF MAPS LIST OF APPENDICES ABBREVIATIONS Page No. INTRODUCTION 1-9 CHAPTER I ADVENT OF ISLAM IN KERALA 10-37 CHAPTER II ARAB TRADE BEFORE THE COMING OF THE PORTUGUESE 38-59 CHAPTER III ARRIVAL OF THE PORTUGUESE AND ITS IMPACT ON THE SOCIETY 60-103 CHAPTER IV THE STRUGGLE OF THE MAPPILAS AGAINST THE BRITISH RULE IN 19™ CENTURY 104-177 CHAPTER V THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT 178-222 CONCLUSION 223-228 GLOSSARY 229-231 MAPS 232-238 BIBLIOGRAPHY 239-265 APPENDICES 266-304 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH - 202 002, INDIA CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis "And - European Struggle by the Mappilas of Malabar 1498-1921 A.D." submitted for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Aligarh Muslim University, is a record of bonafide research carried out by Salahudheen O.P. under our supervision. No part of the thesis has been submitted for award of any degree before. Supervisor Co-Supervisor Prof. Tariq Ahmad Dr. Kunhali.V. Centre of Advanced Study Prof. Department of History Department of History University of Calicut A.M.U. Aligarh Kerala ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My earnest gratitude is due to many scholars teachers and friends for assisting me in this work.