The Moluccas We Do Not Know Much

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download This PDF File

KHAIRUN ISSN Print: 2580-9016 ISSN Online: 2581-1797 Law Journal Khairun Law Journal, Vol. 3 Issue 2, March 2020 Faculty of Law, Khairun University Efektifitas Penegakan Pelanggaran Administrasi Pada Pemiluhan Umum Anggota Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah Oleh Badan Pengawas Pemilihan Umum Tahun 2019 (Studi Terhadap Tugas Badan Pengawas Pemilihan Umum Halmahera Selatan) Ismed A. Gafur Mahsiswa Program Studi Magister Ilmu Hukum Program Pascasarjana Universitas Kahirun, Email : [email protected] Nam Rumkel Dosen Program Studi Magister Ilmu Hukum Program Pascasarjana Universitas Kahirun, Email : [email protected] Abdul Aziz Hakim Dosen Fakultas Hukum Universitas Muhammadiyah Maluku Utara, Email : [email protected] ABSTRACT With the enactment of Law Number 7 of 2017 concerning General Elections, it provides an opportunity for increased democracy by taking into account the violations committed and is the main task of the Regency / City General Election Supervisory Board. The effectiveness of enforcement of administrative violations by BAWASLU South Halmahera Regency based on Article 240 Paragraph (1) Letter (k) and (m) of Law Number 7 of 2017 concerning General Election, has not been maximized in giving decisions to Candidates for DPRD Members of South Halmahera Regency Dapil II Makian Kayoa who have met the formal and material elements in the Administrative Violation Trial examination. In addition, the factors that influence the enforcement of Administrative Violations in the General Election of DPRD Members by BAWASLU South Halmahera in 2019 are the number of personnel and supporting facilities in trial examinations inadequate, between duties and operational funds are not comparable in handling cases of administrative violations. Keywords: Administrative Violations, Concurrent General Elections, District BAWASLU Tasks. -

Foertsch 2016)

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Christopher R. Foertsch for the degree of Master of Arts in Applied Anthropology presented on June 3, 2016. Title: Educational Migration in Indonesia: An Ethnography of Eastern Indonesian Students in Malang, Java. Abstract approved: ______________________________________________________ David A. McMurray This research explores the experience of the growing number of students from Eastern Indonesia who attend universities on Java. It asks key questions about the challenges these often maligned students face as ethnic, linguistic, and religious minorities exposed to the dominant culture of their republic during their years of education. Through interviews and observations conducted in Malang, Java, emergent themes about this group show their resilience and optimism despite discrimination by their Javanese hosts. Findings also reveal their use of social networks from their native islands as a strategy for support and survival. ©Copyright by Christopher R. Foertsch June 3, 2016 All Rights Reserved Educational Migration in Indonesia: An Ethnography of Eastern Indonesian Students in Malang, Java by Christopher R. Foertsch A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Presented June 3, 2016 Commencement June 2017 Master of Arts thesis of Christopher R. Foertsch presented on June 3, 2016 APPROVED: Major Professor, representing Applied Anthropology Director of the School of Language, Culture, and Society Dean of the Graduate School I understand that my thesis will become part of the permanent collection of Oregon State University libraries. My signature below authorizes release of my thesis to any reader upon request. Christopher R. Foertsch, Author ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author expresses sincere appreciation to the many people whose support, advice, and wisdom was instrumental throughout the process of preparing, researching, and writing this thesis. -

Integration and Conflict in Indonesia's Spice Islands

Volume 15 | Issue 11 | Number 4 | Article ID 5045 | Jun 01, 2017 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Integration and Conflict in Indonesia’s Spice Islands David Adam Stott Tucked away in a remote corner of eastern violence, in 1999 Maluku was divided into two Indonesia, between the much larger islands of provinces – Maluku and North Maluku - but this New Guinea and Sulawesi, lies Maluku, a small paper refers to both provinces combined as archipelago that over the last millennia has ‘Maluku’ unless stated otherwise. been disproportionately influential in world history. Largely unknown outside of Indonesia Given the scale of violence in Indonesia after today, Maluku is the modern name for the Suharto’s fall in May 1998, the country’s Moluccas, the fabled Spice Islands that were continuing viability as a nation state was the only place where nutmeg and cloves grew questioned. During this period, the spectre of in the fifteenth century. Christopher Columbus Balkanization was raised regularly in both had set out to find the Moluccas but mistakenly academic circles and mainstream media as the happened upon a hitherto unknown continent country struggled to cope with economic between Europe and Asia, and Moluccan spices reverse, terrorism, separatist campaigns and later became the raison d’etre for the European communal conflict in the post-Suharto presence in the Indonesian archipelago. The transition. With Yugoslavia’s violent breakup Dutch East India Company Company (VOC; fresh in memory, and not long after the demise Verenigde Oost-indische Compagnie) was of the Soviet Union, Indonesia was portrayed as established to control the lucrative spice trade, the next patchwork state that would implode. -

A Floristic Study of Halmahera, Indonesia Focusing on Palms (Arecaceae) and Their Eeds Dispersal Melissa E

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 5-24-2017 A Floristic Study of Halmahera, Indonesia Focusing on Palms (Arecaceae) and Their eedS Dispersal Melissa E. Abdo Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC001976 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Botany Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, and the Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Abdo, Melissa E., "A Floristic Study of Halmahera, Indonesia Focusing on Palms (Arecaceae) and Their eS ed Dispersal" (2017). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3355. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3355 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida A FLORISTIC STUDY OF HALMAHERA, INDONESIA FOCUSING ON PALMS (ARECACEAE) AND THEIR SEED DISPERSAL A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in BIOLOGY by Melissa E. Abdo 2017 To: Dean Michael R. Heithaus College of Arts, Sciences and Education This dissertation, written by Melissa E. Abdo, and entitled A Floristic Study of Halmahera, Indonesia Focusing on Palms (Arecaceae) and Their Seed Dispersal, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Javier Francisco-Ortega _______________________________________ Joel Heinen _______________________________________ Suzanne Koptur _______________________________________ Scott Zona _______________________________________ Hong Liu, Major Professor Date of Defense: May 24, 2017 The dissertation of Melissa E. -

Avifauna Diversity at Central Halmahera North Maluku, Indonesia Zoo Indonesia 2012

Avifauna Diversity at Central Halmahera North Maluku, Indonesia Zoo Indonesia 2012. 21(1): 17-31 AVIFAUNA DIVERSITY AT CENTRAL HALMAHERA NORTH MALUKU, INDONESIA Mohammad Irham Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense, Research Center for Biology, Indonesian Institute of Sciences Widyasatwaloka Building, Jl. Raya Jakarta-Bogor Km. 46, Cibinong 16911, Indonesia Email: [email protected] ABSTRAK Irham, M. Keanekaragaman Avifauna at Weda Bay, Halmahera, Indonesia. 2012 Zoo Indonesia 21(1), 17-31. Survei burung dengan menggunakan metode titik hitung dan jaring telah dilakukan di Halmahera, Maluku Utara di empat lokasi utama yaitu Wosea, Ake Jira, Tofu Blewen dan Bokit Mekot. Sebanyak 70 spesies burung dari 32 famili dijumpai selama penelitian lapangan. Keragaman burung tertinggi ditemukan di Tofu Blewen yaitu 50 spesies (Indeks Shannon = 2.64) kemudian diikuti oleh Ake Jira (48 spesies, Indeks Shannon = 2,63), Wosea (41 spesies, Indeks Shannon = 2,54) dan Boki Mekot (37 spesies, Indeks Shannon = 2,52 ). Berdasarkan Indeks Kesamaan Jaccard, komunitas burung di Wosea jauh berbeda dibandingkan lokasi lain. Gangguan habitat dan ketinggian memperlihatkan pengaruh pada keragaman burung terutama pada jenis-jenis endemik dan terancam seperti komunitas di Wosea. Beberapa jenis burung, terutama paruh bengkok seperti Kakatua Putih, menunjukkan hubungan negatif dengan ketinggian . Kata Kunci: keragaman burung, Halmahera, gangguan habitat, ketinggian ABSTRACT Irham, M. Avifauna diversity at Weda Bay, Halmahera, Indonesia. 2012 Zoo Indonesia 21(1), 17-31. Bird surveys by point counts and mist-nets were carried out in Halmahera, North Moluccas at four locations i.e. Wosea, Ake Jira, Tofu Blewen and Bokit Mekot. A total of 70 birds species from 32 families were recorded during fieldworks. -

Local Trade Networks in Maluku in the 16Th, 17Th and 18Th Centuries

CAKALELEVOL. 2, :-f0. 2 (1991), PP. LOCAL TRADE NETWORKS IN MALUKU IN THE 16TH, 17TH, AND 18TH CENTURIES LEONARD Y. ANDAYA U:-fIVERSITY OF From an outsider's viewpoint, the diversity of language and ethnic groups scattered through numerous small and often inaccessible islands in Maluku might appear to be a major deterrent to economic contact between communities. But it was because these groups lived on small islands or in forested larger islands with limited arable land that trade with their neighbors was an economic necessity Distrust of strangers was often overcome through marriage or trade partnerships. However, the most . effective justification for cooperation among groups in Maluku was adherence to common origin myths which established familial links with societies as far west as Butung and as far east as the Papuan islands. I The records of the Dutch East India Company housed in the State Archives in The Hague offer a useful glimpse of the operation of local trading networks in Maluku. Although concerned principally with their own economic activities in the area, the Dutch found it necessary to understand something of the nature of Indigenous exchange relationships. The information, however, never formed the basis for a report, but is scattered in various documents in the form of observations or personal experiences of Dutch officials. From these pieces of information it is possible to reconstruct some of the complexity of the exchange in MaJuku in these centuries and to observe the dynamism of local groups in adapting to new economic developments in the area. In addition to the Malukans, there were two foreign groups who were essential to the successful integration of the local trade networks: the and the Chinese. -

Inter-Region Economic Analysis to Improve Economic Development Maritime in North Maluku Province

Jurnal Ekonomi dan Studi Pembangunan, 9 (1), 2017 ISSN 2086-1575 E-ISSN 2502-7115 Inter-region Economic Analysis to Improve Economic Development Maritime In North Maluku Province Musdar Muhammd, Devanto, Wildan Syafitri Master Program of Economics Faculty of Economics and Business Brawijaya University Email: [email protected] Received: July 12, 2016; Accepted: October 21, 2016; Published: March 2, 2017 Permalink/DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17977/um002v9i12017p001 Abstract The main purpose of this research to analysis sector and sub-sector development of chartered investment counsel maritime between regions which is bases sector in sub-province and opportunity of job activity at sub- sector fishery of sub-province in North Maluku with observation PDRB sub- province/town during five years (2009-2013). Then, analyses development policy strategy of chartered investment counsel maritime North Maluku. By using technique analyses LQ, multiplier effect, and AHP. The result of analysis shows sub-province Halmahera South and second archipelago Sula of the sub-province that there is sector and sub-sector bases which at most when in comparing to sector and sub-sector bases there is sub-province/town province North Maluku, multiplier effect opportunity of job activity at sub- sector fishery happened in the year 2010 that there is in sub-province/city West Halmahera, South-east Halmahera, East Halmahera North Halmahera, and city of Tidore archipelago’s. In the year of 2013, multiplier effect sub- sector fishery catches there is at sub-province West Halmahera, South Halmahera, and the city of Tidore archipelagoes. Development policy strategy of chartered investment counsel maritime human resource, public service, natural resources with fishery & oceanic requirement in making a preference for development of chartered investment counsel maritime of North Maluku. -

INTRODUCTION Prince Nuku of Tidore Is Recognized As One Of

INTRODUCTION Prince Nuku of Tidore is recognized as one of the national heroes (pahlawan nasional) of Indonesia. He was the leader of a successful rebel- lion against the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, VOC) and its indigenous allies which lasted for more than twenty years. Born as a Tidoran prince between 1725 and 1735, he passed away as the Sultan of Tidore in 1805.1 In 1780 he fled from Tidore seek- ing refuge in East Seram, Halmahera, and the Raja Ampat from where he launched the rebellion. In 1797 he returned to Tidore with his allied forces and conquered the Sultanates of both Bacan and Tidore. During his exile, Nuku had to fight the forces of the three VOC Governments in Maluku: Ternate, Ambon, and Banda.2 Besides possessing better weapon- ry and equipment, the VOC could also mobilize its indigenous subjects from places such as Ambon and Ternate as troops. In addition, the VOC often dispatched support forces such as ships, weaponry, and soldiers to Maluku from Batavia. In 1801, in close collaboration with the English, Nuku managed to defeat the VOC in Ternate and its indigenous ally, the Ternate Sultanate. Prince Nuku and his Tidoran adherents depended to a large extent on the support they received from various groups of Malukans and Papuans and the assistance of the English. It is intriguing to see what strategies he employed to maintain support among the Tidorans at home, his adher- ents in the periphery of Tidore, and even the English. Geographical and historical setting In the early sixteenth century, Maluku—known as the Spice Islands— became the target of European traders who were competing to obtain cloves and nutmegs. -

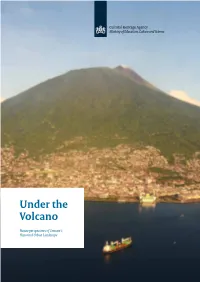

Under the Volcano

Under the Volcano Future perspectives of Ternate’s Historical Urban Landscape Under the Volcano Future perspectives of Ternate’s Historical Urban Landscape Under the Volcano Future perspectives of Ternate’s Historical Urban Landscape Report of the Ternate Conservation and Development Workshop Kota Ternate, 24-28 September 2012 Jean-Paul Corten, Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands Maulana Ibrahim, Universitas Khairun, Ternate, Indonesia Students of Universitas Khairun: Abdul Malik Pellu Arie Hendra Dessy Prawasti Ikbal Akili Irfan Jubbai Marasabessy Kodradi A.K. Sero Sero Rosmiati Hamisi Surahman Marsaoly Members of Ternate Heritage Society: Azwar Ahmad A. Fachrudin A.B. M. Diki Dabi Dabi Ridwan Ade Colophon Department: Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands Ministry of Education, Culture and Science Project name: Ternate Conservation and Development Workshop Version: 1.0 Date: July 2016 Contact: Jean-Paul Corten [email protected] Authors: Jean-Paul Corten, Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands Maulana Ibrahim, Universitas Khairun, Ternate, Indonesia Photo’s: Maulana Ibrahim Cover image: The Island of Ternate seen from the air (Maulana Ibrahim 2012) Design: En Publique, Utrecht Print: Xerox/OTB, The Hague © Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, Amersfoort 2016 Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands P.O.Box 1600 3800 BP Amersfoort the Netherlands culturalheritageagency.nl/en Content 1. Introduction 7 2. Historical Urban Landscapes 9 3. Past developments 11 4. Present situation 15 Urban quality 15 Technical condition 16 Current use 18 Strengths and weaknesses 18 5. Future perspectives 21 Development opportunities and risks 21 Restoration need 22 Participating students of the Khairun University (Maulana Ibrahim 2012) 6 — Map of Northern Maluku 1. -

History of the Moluccan's Cloves As a Global Commodity Hatib

History of the Moluccan's Cloves as a Global Commodity � Hatib Abdul Kadir1 Abstract This paper focuses on the history of spice trade in Moluccas. Using two main approaches of firstly, Braudel, I intend to examine the histoty of spice trade in Moluccas in the 16th century in relation with the changing of the structure of economy that affected the social and political relations of the Moluccans. Secondly, applying Wallerstein approaches, I find out that trading activities from the 16th century until today have created a wide gap between post-colonial Moluccas and the Europeans. To conclude, I argue that economic activities have always been accompanied by forcing political power, such as monopoly and military power. Consequently, they have created unequal relations between the state and society. Keywords: Moluccas, Spice, Braudel, Wallerstein, State-society Relations A. Introduction My research is about the clove trade as a long distance commodity exchange in the sixteenth century. I choose to look at a limited timeframe in order to see the Moluccan trade in connection with Fernand Braudel's work. Braudel focuses on a global trade in the period that centered in the Mediterranean during the sixteenth century. This paper examines the kind of social changes occurring in Moluccan society when cloves became a highly valued commodity in trade with the Portuguese during the sixteenth century. The aim of the paper is to see how the patterns of this trade represent the Portuguese as the 'core' and the Moluccans as the 'periphery.' By using Braudel's approach, the aims of the paper are to explore the global history of society that is connected through unfair relations or colonization. -

Kajian Pelayanan Peti Kemas Di Pelabuhan A. Yani Ternate

International Refereed Journal of Engineering and Science (IRJES) ISSN (Online) 2319-183X, (Print) 2319-1821 Volume 5, Issue 9 (September 2016), PP.28-33 Service Improvement at Container Port of Ahmad Yani Ternate North Maluku Province of Indonesia Paulus Raga Senior Researcher at the Sea Transportation Research Center, River, Lake, and Ferry Research and Development Agency of Transportation Indonesia Abstract: The port of Ahmad Yani Ternate is the node local trade and an opening through trade channels of logistics and services between regional and national levels. Loading and unloading of containers through the Port of Ahmad Yani Ternate increased during the period from 2009 to 2013. Therefore, accompanied economic growth of Ternate city is significant. The tendency of loading and unloading activities at the Port of Ahmad Yani Ternate like container unloading more than loaded, so loading and unloading of general cargo and bag cargo decreased by overloading into the packaging of logistics in containers. This study aimed to evaluate the quality of services and efforts to increase container service at the Port Ahmad Yani Ternate. The analysis technique is used in this study by using Multi Criteria Analysis. Ahmad Yani Piers service facilities such as under deck, side deck and upper deck repairs damaged due to heavy and port facilities such as a field efforts to improve service quality container Port of Ahmad Yani Ternate on a scale first priority is the short-term reclamation of 3,000 m2 with the performance appraisal scale is at a score of 8 to 10; The second priority, medium-term reclamation of 6,160 m2 with the performance appraisal scale is at a score of 6 to 8 and the third priority, long-term reclamation of 49 424 m2 with the performance appraisal scale is at a score of 4 to 6. -

Zoologische Mededelingen Uitgegeven Door Het

ZOOLOGISCHE MEDEDELINGEN UITGEGEVEN DOOR HET RIJKSMUSEUM VAN NATUURLIJKE HISTORIE TE LEIDEN (MINISTERIE VAN CULTUUR, RECREATIE EN MAATSCHAPPELIJK WERK) Deel 56 no. 7 7 mei 1982 BIRD RECORDS FROM THE MOLUCCAS by G. F. MEES Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leiden Vom 2.-15. August 1876 sammelte Teysmann Vögel bei Kajeli, wovon niemals eine Liste publiciert wurde, da sie nach Leiden gelangten. E. Stresemann (1914b: 360). INTRODUCTION For the past thirty years I have, from time to time, come across bird material and literature records which have added localities and in a few instances have ad• ded new species, to Van Bemmel's (1948) list of birds of the Moluccan Islands and its supplement, published five years later (Van Bemmel & Voous, 1953). I have kept notes of these additions with the vague idea of perhaps, some time in the future, publishing a revised edition of the list of the avifauna of the Moluc• cas, zoogeographically one of the most interesting regions of the world. The sum total of my notes to date would hardly have justified publication, were it not for the fact that a new list of Moluccan birds was in the course of preparation by the late C. M. N. White, and is to be posthumously completed and published (cf. Benson, 1979; Cranbrook, 1980). This made it desirable to have my notes published, so that they will be available for inclusion in the new list. Ornithological activity in the Moluccas since the publication of Van BemmePs list has been limited. Many of De Haan's results were already incorporated in the paper by Van Bemmel & Voous (1953); subsequently two new subspecies from his collections were described by Jany (1955).