A Reflection on a Peripheral Movement 561

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integration and Conflict in Indonesia's Spice Islands

Volume 15 | Issue 11 | Number 4 | Article ID 5045 | Jun 01, 2017 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Integration and Conflict in Indonesia’s Spice Islands David Adam Stott Tucked away in a remote corner of eastern violence, in 1999 Maluku was divided into two Indonesia, between the much larger islands of provinces – Maluku and North Maluku - but this New Guinea and Sulawesi, lies Maluku, a small paper refers to both provinces combined as archipelago that over the last millennia has ‘Maluku’ unless stated otherwise. been disproportionately influential in world history. Largely unknown outside of Indonesia Given the scale of violence in Indonesia after today, Maluku is the modern name for the Suharto’s fall in May 1998, the country’s Moluccas, the fabled Spice Islands that were continuing viability as a nation state was the only place where nutmeg and cloves grew questioned. During this period, the spectre of in the fifteenth century. Christopher Columbus Balkanization was raised regularly in both had set out to find the Moluccas but mistakenly academic circles and mainstream media as the happened upon a hitherto unknown continent country struggled to cope with economic between Europe and Asia, and Moluccan spices reverse, terrorism, separatist campaigns and later became the raison d’etre for the European communal conflict in the post-Suharto presence in the Indonesian archipelago. The transition. With Yugoslavia’s violent breakup Dutch East India Company Company (VOC; fresh in memory, and not long after the demise Verenigde Oost-indische Compagnie) was of the Soviet Union, Indonesia was portrayed as established to control the lucrative spice trade, the next patchwork state that would implode. -

A Floristic Study of Halmahera, Indonesia Focusing on Palms (Arecaceae) and Their Eeds Dispersal Melissa E

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 5-24-2017 A Floristic Study of Halmahera, Indonesia Focusing on Palms (Arecaceae) and Their eedS Dispersal Melissa E. Abdo Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC001976 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Botany Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, and the Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Abdo, Melissa E., "A Floristic Study of Halmahera, Indonesia Focusing on Palms (Arecaceae) and Their eS ed Dispersal" (2017). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3355. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3355 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida A FLORISTIC STUDY OF HALMAHERA, INDONESIA FOCUSING ON PALMS (ARECACEAE) AND THEIR SEED DISPERSAL A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in BIOLOGY by Melissa E. Abdo 2017 To: Dean Michael R. Heithaus College of Arts, Sciences and Education This dissertation, written by Melissa E. Abdo, and entitled A Floristic Study of Halmahera, Indonesia Focusing on Palms (Arecaceae) and Their Seed Dispersal, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Javier Francisco-Ortega _______________________________________ Joel Heinen _______________________________________ Suzanne Koptur _______________________________________ Scott Zona _______________________________________ Hong Liu, Major Professor Date of Defense: May 24, 2017 The dissertation of Melissa E. -

Influence of Conflict on Migration at Moluccas Province

INFLUENCE OF CONFLICT ON MIGRATION AT MOLUCCAS PROVINCE Maryam Sangadji Fakultas Ekonomi Universitas Pattimura Ambon Abstraksi Konflik antara komunitas islam dan Kristen di propinsi Maluku menyebabkan lebih dari sepertiga populasi penduduknya atau 2,1 juta orang menjadi IDP (pengungsi) serta mengalami kemiskinan dan penderitaan. Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk meneliti proses, dampak dan masalah yang dihadapi para IDP. Hasil analisis kualitatif deskriptif menunjukkan bahwa proses migrasi IDP ditentukan oleh tingkat intensitas konflik dan lebih marginal pada lokasi IDP. Disamping itu terlampau banyak masalah yang timbul dalam mengatasi IDP baik internal maupun eksternal. Kata kunci: konflik komunitas, Maluku. The phenomena of population move as the result of conflict among communities is a problem faced by development, due to population mobility caused by conflict occurs in a huge quantity where this population is categorized as IDP with protection and safety as the reason. The condition is different if migration is performed with economic motive, this means that they have calculate cost and benefit from the purposes of making migration. Since 1970s, there are many population mobility that are performed with impelled manner (Petterson, W, 1996), the example is Africa where due to politic, economic and social condition the individual in the continent have no opportunity to calculate the benefit. While in Indonesia the reform IDP is very high due to conflict between community as the symbol of religion and ethnic. This, of course, contrast with the symbol of Indonesian, namely “Bhinneka Tunggal Ika”, different but one soul, this condition can be seen from 683 multiethnic and there are 5 religions in Indonesia. In fact, if the differences are not managed, the conflict will appear, and this condition will end on open conflict. -

Avifauna Diversity at Central Halmahera North Maluku, Indonesia Zoo Indonesia 2012

Avifauna Diversity at Central Halmahera North Maluku, Indonesia Zoo Indonesia 2012. 21(1): 17-31 AVIFAUNA DIVERSITY AT CENTRAL HALMAHERA NORTH MALUKU, INDONESIA Mohammad Irham Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense, Research Center for Biology, Indonesian Institute of Sciences Widyasatwaloka Building, Jl. Raya Jakarta-Bogor Km. 46, Cibinong 16911, Indonesia Email: [email protected] ABSTRAK Irham, M. Keanekaragaman Avifauna at Weda Bay, Halmahera, Indonesia. 2012 Zoo Indonesia 21(1), 17-31. Survei burung dengan menggunakan metode titik hitung dan jaring telah dilakukan di Halmahera, Maluku Utara di empat lokasi utama yaitu Wosea, Ake Jira, Tofu Blewen dan Bokit Mekot. Sebanyak 70 spesies burung dari 32 famili dijumpai selama penelitian lapangan. Keragaman burung tertinggi ditemukan di Tofu Blewen yaitu 50 spesies (Indeks Shannon = 2.64) kemudian diikuti oleh Ake Jira (48 spesies, Indeks Shannon = 2,63), Wosea (41 spesies, Indeks Shannon = 2,54) dan Boki Mekot (37 spesies, Indeks Shannon = 2,52 ). Berdasarkan Indeks Kesamaan Jaccard, komunitas burung di Wosea jauh berbeda dibandingkan lokasi lain. Gangguan habitat dan ketinggian memperlihatkan pengaruh pada keragaman burung terutama pada jenis-jenis endemik dan terancam seperti komunitas di Wosea. Beberapa jenis burung, terutama paruh bengkok seperti Kakatua Putih, menunjukkan hubungan negatif dengan ketinggian . Kata Kunci: keragaman burung, Halmahera, gangguan habitat, ketinggian ABSTRACT Irham, M. Avifauna diversity at Weda Bay, Halmahera, Indonesia. 2012 Zoo Indonesia 21(1), 17-31. Bird surveys by point counts and mist-nets were carried out in Halmahera, North Moluccas at four locations i.e. Wosea, Ake Jira, Tofu Blewen and Bokit Mekot. A total of 70 birds species from 32 families were recorded during fieldworks. -

Local Trade Networks in Maluku in the 16Th, 17Th and 18Th Centuries

CAKALELEVOL. 2, :-f0. 2 (1991), PP. LOCAL TRADE NETWORKS IN MALUKU IN THE 16TH, 17TH, AND 18TH CENTURIES LEONARD Y. ANDAYA U:-fIVERSITY OF From an outsider's viewpoint, the diversity of language and ethnic groups scattered through numerous small and often inaccessible islands in Maluku might appear to be a major deterrent to economic contact between communities. But it was because these groups lived on small islands or in forested larger islands with limited arable land that trade with their neighbors was an economic necessity Distrust of strangers was often overcome through marriage or trade partnerships. However, the most . effective justification for cooperation among groups in Maluku was adherence to common origin myths which established familial links with societies as far west as Butung and as far east as the Papuan islands. I The records of the Dutch East India Company housed in the State Archives in The Hague offer a useful glimpse of the operation of local trading networks in Maluku. Although concerned principally with their own economic activities in the area, the Dutch found it necessary to understand something of the nature of Indigenous exchange relationships. The information, however, never formed the basis for a report, but is scattered in various documents in the form of observations or personal experiences of Dutch officials. From these pieces of information it is possible to reconstruct some of the complexity of the exchange in MaJuku in these centuries and to observe the dynamism of local groups in adapting to new economic developments in the area. In addition to the Malukans, there were two foreign groups who were essential to the successful integration of the local trade networks: the and the Chinese. -

Inter-Region Economic Analysis to Improve Economic Development Maritime in North Maluku Province

Jurnal Ekonomi dan Studi Pembangunan, 9 (1), 2017 ISSN 2086-1575 E-ISSN 2502-7115 Inter-region Economic Analysis to Improve Economic Development Maritime In North Maluku Province Musdar Muhammd, Devanto, Wildan Syafitri Master Program of Economics Faculty of Economics and Business Brawijaya University Email: [email protected] Received: July 12, 2016; Accepted: October 21, 2016; Published: March 2, 2017 Permalink/DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17977/um002v9i12017p001 Abstract The main purpose of this research to analysis sector and sub-sector development of chartered investment counsel maritime between regions which is bases sector in sub-province and opportunity of job activity at sub- sector fishery of sub-province in North Maluku with observation PDRB sub- province/town during five years (2009-2013). Then, analyses development policy strategy of chartered investment counsel maritime North Maluku. By using technique analyses LQ, multiplier effect, and AHP. The result of analysis shows sub-province Halmahera South and second archipelago Sula of the sub-province that there is sector and sub-sector bases which at most when in comparing to sector and sub-sector bases there is sub-province/town province North Maluku, multiplier effect opportunity of job activity at sub- sector fishery happened in the year 2010 that there is in sub-province/city West Halmahera, South-east Halmahera, East Halmahera North Halmahera, and city of Tidore archipelago’s. In the year of 2013, multiplier effect sub- sector fishery catches there is at sub-province West Halmahera, South Halmahera, and the city of Tidore archipelagoes. Development policy strategy of chartered investment counsel maritime human resource, public service, natural resources with fishery & oceanic requirement in making a preference for development of chartered investment counsel maritime of North Maluku. -

INTRODUCTION Prince Nuku of Tidore Is Recognized As One Of

INTRODUCTION Prince Nuku of Tidore is recognized as one of the national heroes (pahlawan nasional) of Indonesia. He was the leader of a successful rebel- lion against the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, VOC) and its indigenous allies which lasted for more than twenty years. Born as a Tidoran prince between 1725 and 1735, he passed away as the Sultan of Tidore in 1805.1 In 1780 he fled from Tidore seek- ing refuge in East Seram, Halmahera, and the Raja Ampat from where he launched the rebellion. In 1797 he returned to Tidore with his allied forces and conquered the Sultanates of both Bacan and Tidore. During his exile, Nuku had to fight the forces of the three VOC Governments in Maluku: Ternate, Ambon, and Banda.2 Besides possessing better weapon- ry and equipment, the VOC could also mobilize its indigenous subjects from places such as Ambon and Ternate as troops. In addition, the VOC often dispatched support forces such as ships, weaponry, and soldiers to Maluku from Batavia. In 1801, in close collaboration with the English, Nuku managed to defeat the VOC in Ternate and its indigenous ally, the Ternate Sultanate. Prince Nuku and his Tidoran adherents depended to a large extent on the support they received from various groups of Malukans and Papuans and the assistance of the English. It is intriguing to see what strategies he employed to maintain support among the Tidorans at home, his adher- ents in the periphery of Tidore, and even the English. Geographical and historical setting In the early sixteenth century, Maluku—known as the Spice Islands— became the target of European traders who were competing to obtain cloves and nutmegs. -

Reef Fishing Resources and Their Utilization in Southwest Maluku Regency, Indonesia

Volume 6, Issue 6, June – 2021 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology ISSN No:-2456-2165 Reef Fishing Resources and their Utilization in Southwest Maluku Regency, Indonesia Syachrul Arief Staff Center for Research, Promotion, and Cooperation Geospatial Information Agency Indonesia Cibinong-Bogor, Indonesia Abstract:- Remote islands in Southwest Maluku have cause much limiting geomorphologically on developing received the government's attention concerning collecting agricultural on the mainland (Herman, 1991), therefore the information about coastal resources. This research was people putting the sector of business marine as an alternative conducted on the islands of Leti, Moa, Lakor, and superior in development. The fisheries sector is expected Metimialam, and Metimiarang. The purpose of the study to become a leader in developing drought-prone regions such was to obtain data and information on reef fish resources as Maluku Barat Daya (Edrus and Bustaman, 2005), which and their utilization. The method used in collecting data encourages trade in the goods and services sector, followed by and information is a visual census in belt transect an area agriculture and tourism. of 250 m 2 and semi-structured interviews. Research results on 2 1 location of sampling data show that at least In subsequent developments, the issue of small islands has 309 species of reef fish of 45 tribes. Diversity varies on bordering neighboring countries became the government's the value of 8 to 18. Community diversity is classified as attention (Saputro et al ., 2005), especially after the events of moderate level. Individual densities per square meter are the seizure of Ligitan and Sipadan. -

Adat Law 'Larwul Ngabal' in the Implementation of Regional Autonomy Policy

Scholars International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice Abbreviated Key Title: Sch Int J Law Crime Justice ISSN 2616-7956 (Print) |ISSN 2617-3484 (Online) Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates Journal homepage: https://saudijournals.com/sijlcj Review Article Adat Law ‘Larwul Ngabal’ in the Implementation of Regional Autonomy Policy Nam Rumkel* Faculty of Law, Khairun University, Indonesia DOI: 10.36348/sijlcj.2020.v03i04.007 | Received: 01.04.2020 | Accepted: 08.04.2020 | Published: 14.04.2020 *Corresponding author: Nam Rumkel Abstract The purpose of this study was to find the legal position of Larwul Ngabal in the regional autonomy policy in the Kei Islands. This study uses a sociological-anthropological juridical approach that sees law as a social phenomenon that can be observed in people's life experiences. As an empirical legal research with a sociological-anthropological juridical approach, the data analysis technique is descriptive analysis. The results showed that the existence of Adat Law Larwul Ngabal in supporting the implementation of regional autonomy based on local wisdom in the Kei Islands both in the implementation of governance in Southeast Maluku Regency and Tual City was formally visible with the preparation of several regional regulations based on the values of customary values, but substantially have not been optimized in various local government policies in order to create a safe, fair and prosperous society, because they can be influenced by various factors such as legal factors, political factors and economic factors. Keywords: Adat Law, Larwul Ngabal, Regional Autonomy. Copyright @ 2020: This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution license which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium for non-commercial use (NonCommercial, or CC-BY-NC) provided the original author and source are credited. -

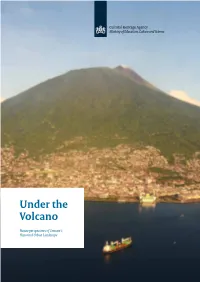

Under the Volcano

Under the Volcano Future perspectives of Ternate’s Historical Urban Landscape Under the Volcano Future perspectives of Ternate’s Historical Urban Landscape Under the Volcano Future perspectives of Ternate’s Historical Urban Landscape Report of the Ternate Conservation and Development Workshop Kota Ternate, 24-28 September 2012 Jean-Paul Corten, Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands Maulana Ibrahim, Universitas Khairun, Ternate, Indonesia Students of Universitas Khairun: Abdul Malik Pellu Arie Hendra Dessy Prawasti Ikbal Akili Irfan Jubbai Marasabessy Kodradi A.K. Sero Sero Rosmiati Hamisi Surahman Marsaoly Members of Ternate Heritage Society: Azwar Ahmad A. Fachrudin A.B. M. Diki Dabi Dabi Ridwan Ade Colophon Department: Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands Ministry of Education, Culture and Science Project name: Ternate Conservation and Development Workshop Version: 1.0 Date: July 2016 Contact: Jean-Paul Corten [email protected] Authors: Jean-Paul Corten, Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands Maulana Ibrahim, Universitas Khairun, Ternate, Indonesia Photo’s: Maulana Ibrahim Cover image: The Island of Ternate seen from the air (Maulana Ibrahim 2012) Design: En Publique, Utrecht Print: Xerox/OTB, The Hague © Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, Amersfoort 2016 Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands P.O.Box 1600 3800 BP Amersfoort the Netherlands culturalheritageagency.nl/en Content 1. Introduction 7 2. Historical Urban Landscapes 9 3. Past developments 11 4. Present situation 15 Urban quality 15 Technical condition 16 Current use 18 Strengths and weaknesses 18 5. Future perspectives 21 Development opportunities and risks 21 Restoration need 22 Participating students of the Khairun University (Maulana Ibrahim 2012) 6 — Map of Northern Maluku 1. -

Implementation of Precautionaryprinciple in Gold Mine Exploitation in Romang Island, Southwest Maluku Regency by PT

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 9, ISSUE 01, JANUARY 2020 ISSN 2277-8616 Implementation Of Precautionaryprinciple In Gold Mine Exploitation In Romang Island, Southwest Maluku Regency By PT. Gemala Borneo Utama Based On Law Number 32 Year 2009 La Ode Angga, Barzah Latupono, Muchtar Anshary Hamid Labetubun, Sabri Fataruba Abstract : Research entitled The Application of Precautionary Principle Prudential Principles in Gold Mine Exploitation in Romang Island, Southwest Maluku District By PT. Gemala Borneo Utama Based on Law Number 32 Year 2009, the aim is to find out and analyze the applicati on of the Precautionary Principle by PT. Gemala Borneo Utama in the Exploitation of a Gold Mine on Romang Island, Southwest Maluku Regency, Based on Law No. 32 of 2009 concerning Environmental Protection and Management (UUPPLH-2009), (State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia No. 140, Supplement to the State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia No. 5059), whether the precautionary principle has been applied by PT. Gemala Borneo Utama before mining activities are carried out? This research was conducted using Normaf's juridical approach which is a descriptive analysis of qualitative research. This study aims to describe what happened in the implementation of Gold Mine Exploitation on Romang Isl and, Southwest Maluku Regency by PT. Gemala Borneo Utama. Does the implementation of exploitation apply the precautionary principle as regulated in Article 2 letter UUPPLH. The answer that can be obtained in this study is that PT. Gemala Borneo Utama does not apply the precautionary principle in the exploitation of a gold mine on Romang Island, Southwest Maluku Regency, this can be seen from the results of laboratory analysis that is proven to use mercury (Hg). -

Kajian Pelayanan Peti Kemas Di Pelabuhan A. Yani Ternate

International Refereed Journal of Engineering and Science (IRJES) ISSN (Online) 2319-183X, (Print) 2319-1821 Volume 5, Issue 9 (September 2016), PP.28-33 Service Improvement at Container Port of Ahmad Yani Ternate North Maluku Province of Indonesia Paulus Raga Senior Researcher at the Sea Transportation Research Center, River, Lake, and Ferry Research and Development Agency of Transportation Indonesia Abstract: The port of Ahmad Yani Ternate is the node local trade and an opening through trade channels of logistics and services between regional and national levels. Loading and unloading of containers through the Port of Ahmad Yani Ternate increased during the period from 2009 to 2013. Therefore, accompanied economic growth of Ternate city is significant. The tendency of loading and unloading activities at the Port of Ahmad Yani Ternate like container unloading more than loaded, so loading and unloading of general cargo and bag cargo decreased by overloading into the packaging of logistics in containers. This study aimed to evaluate the quality of services and efforts to increase container service at the Port Ahmad Yani Ternate. The analysis technique is used in this study by using Multi Criteria Analysis. Ahmad Yani Piers service facilities such as under deck, side deck and upper deck repairs damaged due to heavy and port facilities such as a field efforts to improve service quality container Port of Ahmad Yani Ternate on a scale first priority is the short-term reclamation of 3,000 m2 with the performance appraisal scale is at a score of 8 to 10; The second priority, medium-term reclamation of 6,160 m2 with the performance appraisal scale is at a score of 6 to 8 and the third priority, long-term reclamation of 49 424 m2 with the performance appraisal scale is at a score of 4 to 6.