Devo-Health : What and Why? (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PART 1 Primary Care Commissioning Committee 2019/20

PART 1 Primary Care Commissioning Committee 2019/20 Date of Meeting: 14 February 2020 Agenda Item: 2.4 Subject: Application to close the York House Surgery (YHS) site Reporting Officer: Sarah Crossley (Author: Sarah Hickman) Aim of Paper: To provide the Primary Care Assurance Sub-committee with the necessary information to enable them to make a decision regarding the application from Heywood Health to close the YHS site Governance route prior to Primary Care Meeting Date Objective/Outcome Commissioning Committee Primary Care Commissioning Committee Select date of meeting. Click to Select Primary Care Assurance Sub - Committee Select date of meeting. Click to Select Primary Care Innovation and Transformation Select date of meeting. Click to Select Sub-Committee Primary Care Assurance and Transformation Select date of meeting. Click to Select Sub - Committee IM&T Group Select date of meeting. Click to Select Other Click here to enter text. Primary Care Commissioning Committee Approval/Decision Resolution Required: Recommendation The Primary Care Assurance Sub-committee are requested to review the attached paper regarding the application to close the YHS site and make a recommendation to the Primary Care Commissioning Committee as to whether this is supported by members Link to Strategic Objectives Contributes to: (Select Yes or No) SO1: To be a high performing CCG, deliver our statutory duties and use Yes our available resources innovatively to deliver the best outcomes for our population. SO2: To deliver on the outcomes of the Locality -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Council, 20/01/2016 18:15

Legal & Governance Reform David Wilcock Head of Legal and Governance Reform Governance & Committee Services Floor 2, Number One Riverside, Smith Street, Rochdale, OL16 1XU Phone: 01706 647474 Website: www.rochdale.gov.uk To: All Members of the Council Enquiries to: Peter Thompson e-mail: [email protected] Telephone: 01706 924715 Date: 12th January 2016 Dear Councillor, You are requested to attend the meeting of Council to be held in the Council Chamber at Rochdale Town Hall on Wednesday, 20th January 2016 at 6.15 pm. Deadlines for submissions in respect of this meeting are as follows: – Tuesday before Council Noon Notification of questions to representatives on Joint (19th January 2016) Authorities and Outside Bodies and to Portfolio Holders and Committee Chairs. Notification of amendments to proposals and recommendations being submitted to Council. Notifications should be forwarded to Mark Hardman and Peter Thompson, on behalf of the Chief Executive. The agenda and supporting papers are attached. If you require advice on any agenda item involving a possible Declaration of Interest which could affect your right to speak and/or vote, please contact staff in the Governance and Committee Services Team at least 24 hours in advance of the meeting. Yours Faithfully David Wilcock Head of Legal and Governance Reform Rochdale Borough Council COUNCIL Wednesday, 20th January 2016 at 6.15 pm Council Chamber - Rochdale Town Hall AGENDA Apologies for Absence 1. Mayor's Announcements 2. Declarations of Interest 1 - 2 Members are requested to indicate at this stage any items on the agenda in which they intend to declare an interest. -

Pub of the Month

: ee 1982 THE MANCHESTER BEER DRINKER'S MONTHLY MAGAZINE ~ PUB OF THE MONTH | South Manchester's Pub of the Month for March is the Swan with Two Necks, Princes Street, Stockport. The pub is a haven amongst the shopping precinct and has remained unspoilt as Merseyway was developed around it. The tenants, Bernie and Irene Smith, have been at the pub for 8 years, having previously had the tenancy of the now demolished Robin Hood on Brinksway. Bernie is currently president of Stockport & District LVA and Irene is past Chairlady. The Swan with Two Necks provides an extensive and reasonably priced lunchtime menu and tea and coffee are also available for the weary shopper. The social/ presentation night is on Thursday 25th March, which is also Bernie and Irene's 8th anniversary in the pub. All members and friends are invited to come along. REAL ALE IN FLIXTON Xeni ann io : Real ale has reappeared at the Garricks Head and the Fox and Hounds in Elixton, Licensees at the Garricks are Tony and Elaine Copeland, who had the Oxford in Manchester until it closed two years ago. HOP ONTO A PLANE News of Greenalls takeover of the Arrowsmith bit of the failed Laker organisation will be greeted with dancing in the streets of America. Not only will English beer from the wood now be available in Pittsburgh P.A. and Des Moines lowa, but New Yorkers will be able to avail themselves of the services of Fred Dibnah Esq, brick edifice destroyer extraordinaire,to chop down unwanted skyscrapers. Reciprocal arrangements may’ mean American holidaymakers being mugged in Runcorn. -

Where Can I View Documents and Respond to the Greater Manchester Bus Consultation?

Where can I view documents and respond to the Greater Manchester bus consultation? All documents relating to the consultation and links to the long-form and short-form questionnaires can be accessed online at gmconsult.org. Hard copies of the documents can be viewed at public buildings across Greater Manchester, which are listed below. Long-form and short-form questionnaires and freepost envelopes will also be available for you to submit a response to the consultation. Bolton Bolton Town Hall, Victoria Square, Bolton, BL1 1RU One Stop Shop Bolton Council, Victoria Square, Bolton, BL1 1RJ Blackrod Library, Church Street, Blackrod, Bolton, BL6 5EQ Breightmet Library, Breightmet Fold Lane, Breightmet, Bolton, BL2 6NT Bromley Cross Library, Toppings Estate, Bromley Cross, Bolton, BL7 9JU Central Library, Le Mans Crescent, Bolton, BL1 1SE Farnworth Library, Market Street, Farnworth, Bolton, BL4 7PG Harwood Library, Gate Fold, Harwood, Bolton, BL2 3HN High Street Library, High Street, Bolton, BL3 6SZ Horwich Library, Jones Street, Horwich, Bolton, BL6 6SZ Little Lever Library, Coronation Square, Little Lever, Bolton, BL3 1LP Westhoughton Library, Library Street, Westhoughton, Bolton, BL5 3AU Bury Bury Town Hall, Knowsley Street, Bury, BL9 0ST Bury Library, Manchester Road, Bury, BL9 0DG Prestwich Library, Longfield Centre, Prestwich, Bury, M25 1AY Radcliffe Library, Stand Lane, Radcliffe, Bury, M26 1JA Ramsbottom Library, Carr Street, Ramsbottom, Bury, BL0 9AE Tottington Centre, Market Street, Tottington, Bury, BL8 3LL Manchester Manchester -

Agenda Reports Pack (Public) 13/12/2012, 18.15

Public Document Pack CORPORATE SERVICES Service Director Linda Fisher GOVERNANCE AND COMMITTEE SERVICES TEAM PO Box 15, Town Hall, Rochdale, OL16 1AB DX22831 ROCHDALE Tel: (01706) 647474 Fax: (01706) 924705 Website: www.rochdale.gov.uk To: All Members of the Overview and Scrutiny Enquiries to: Peter Thompson Committee e-mail: [email protected] Extension: 4715 Date: 5th December 2012 Dear Councillor OVERVIEW AND SCRUTINY COMMITTEE You are requested to attend the meeting of the Overview and Scrutiny Committee to be held in Committee Rooms 1 and 2 at Rochdale Town Hall on 13 th December 2012 commencing at 6.15 pm. The agenda and supporting papers are attached. If you require advice on any agenda item involving a possible Declaration of Interest which could affect your right to speak and/or vote, please contact staff in the Governance and Committee Services Team at least 24 hours in advance of the meeting. Yours faithfully Linda Fisher Service Director Overview and Scrutiny Committee Membership 2012/13:- Councillor Daalat Ali Councillor Malcolm Boriss Councillor Robert Clegg Councillor Karen Danczuk Councillor Neil Emmott Councillor Susan Emmott Councillor Pat Greenall Councillor Michael Holly Councillor Andy Kelly Councillor Liam O'Rourke Councillor Martin Rodgers ROCHDALE METROPOLITAN BOROUGH COUNCIL OVERVIEW AND SCRUTINY COMMITTEE 13 th December 2012 at 6.15 pm Committee Rooms 1 and 2, Rochdale Town Hall A G E N D A Apologies for Absence 1. Declarations of Interest Members are requested to indicate at this stage any items on the agenda in which they intend to declare an interest. Members are reminded that, in accordance with the Localism Act 2011 and the Council's newly adopted Code of Conduct, they must declare the nature of any personal or discloseable pecuniary interest required of them and, in the case of any discloseable pecuniary interest withdraw from the meeting during consideration of the item, unless permitted otherwise within the Code of Conduct. -

Manchester City Region

Manchester City Region - Demand and Aspirations of Minority Ethnic communities Final Report Manchester City Region - Demand and Aspirations of Minority Ethnic communities Final Report December 2006 ECOTEC Tower Business Centre Portland Tower Portland Street Manchester M1 3LF T +44 (0)161 238 4965 F +44 (0)161 238 4966 www.ecotec.com Acknowledgements This report has been commissioned as one part of the Making Housing Count in the Manchester City Region research project. It has been overseen by the Making Housing Count Project Sponsors' Group (PSG) as well as a Technical Sounding Board and these have provided useful feedback on findings. Particular thanks are due to all those who have helped to set up, or participated in the interviews and focus groups, without which this research would not have been possible. Census output used in this report is Crown Copyright 2003. Crown copyright material is reproduced with the permission of the Controller of HMSO and the Queen's Printer for Scotland. Click-use License No. C2006010569 Contents PAGE Executive Summary............................................................................................. 1 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................... 6 2.0 Scope and Methodology ....................................................................... 8 3.0 National Context.................................................................................. 12 3.1 Introduction ..............................................................................................................12 -

All Notices Gazette

ALL NOTICES GAZETTE CONTAINING ALL NOTICES PUBLISHED ONLINE ON 19 APRIL 2016 PRINTED ON 20 APRIL 2016 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY | ESTABLISHED 1665 WWW.THEGAZETTE.CO.UK Contents State/2* Royal family/ Parliament & Assemblies/3* Honours & Awards/ Church/ Environment & infrastructure/4* Health & medicine/ Other Notices/10* Money/ Companies/11* People/79* Terms & Conditions/110* * Containing all notices published online on 19 April 2016 STATE STATE Departments of State CROWN OFFICE 2524905The Queen has been pleased by Royal Warrant under Her Royal Sign Manual dated 13 April 2016 to appoint Timothy King, Esquire, to the Office of District Judge (Magistrates’ Courts), commencing on and from the 20 April 2016, in accordance with the Courts Act 2003. G. A. Bavister (2524905) Honours & awards State Awards ORDER OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE 2524904CENTRAL CHANCERY OF THE ORDERS OF KNIGHTHOOD St. James’s Palace, London S.W.1. 19 April 2016 THE QUEEN has directed that the appointment of Jawaid Mohammed ISHAQ to be a Member of the Civil Division of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, dated 17 June 2000, shall be cancelled and annulled and that his name shall be erased from the Register of the said Order. (2524904) STATE APPOINTMENTS DEPUTY2524906 LIEUTENANT COMMISSION LIEUTENANCY OF CAMBRIDGESHIRE The Lord-Lieutenant of Cambridgeshire, Sir Hugh Duberly KCVO, CBE, has appointed the following to be Deputy Lieutenants of Cambridgeshire: Lady DE RAMSEY The Rt Hon Lord LANSLEY CBE Mrs Belinda SUTTON Gillian Beasley OBE Clerk to the Lieutenancy 12 April -

Inclusion Strategy Project Report

ROCHDALE INCLUSION STRATEGY PROJECT REPORT CONTENTS 1. Summary of recommendations 2 2. Project Brief 3 3. Methodology 3 4. Rochdale borough Context 4 5. National Policy Context 14 6. Areas for Development 16 7. A Shared View of Inclusion 17 8. Early Identification of Needs 20 9. Supporting Pupils’ Social, Emotional and Mental Health Needs 24 10. A preventative Pupil Referral Service Offer 27 11. A Continuum of SEND Provision 33 12. Strategic Accountability 42 13. References 46 Appendix 1: A note on SEND Data 47 Appendix 2: Action Plan 48 Appendix 3: Croydon Wedge of Nurture 54 Linda Wright, Inclusion Strategy Consultant, February 2020 1 1. SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS Area for development Recommendations 1 Agree a shared view of Agree a set of principles to underpin a Rochdale approach to inclusion which inclusion and how to secure will support effective practice improved outcomes, drawing Develop a flexible PRU offer with a focus on preventing exclusion on a stronger evidence base Work with college or AP providers to commission KS4 vocational provision for successful inclusive Review Fair Access protocols in context of developing preventative PRU practice interventions Consider an inclusion champion with a strong track record teaching in challenging settings to drive implementation of Rochdale’s inclusion strategy 2 Define and agree the level of Ensure a graduated response to meeting the needs of pupils with additional complexity mainstream needs is embedded in primary and secondary school practice schools should manage and Offer -

Printed Minutes PDF 91 KB

Minutes of: LICENSING AND SAFETY PANEL Date of Meeting: 28 November 2017 Present: Councillor D Jones (in the Chair) Councillors P Adams, N Bayley, I Bevan, R Hodkinson, A McKay, Sarah Southworth, J Walker and S Wright Also in attendance: Public Attendance: No members of the public were present at the meeting. Apologies for Absence:Councillor J Grimshaw and Councillor O Kersh LSP.279 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST There were no declarations of interest raised in relation to any items on the agenda. LSP.280 MINUTES OF THE LAST MEETING Delegated decision: That the Minutes of the Licensing and Safety Panel meeting held on 19 October 2017, be approved as a correct record and signed by the Chair. LSP.281 PUBLIC QUESTION TIME There were no questions raised under this item. LSP.282 OPERATIONAL REPORT The Assistant Director (Localities) submitted a report advising Members on operational issues within the Licensing Service. The report set out updates in respect of the following issues: Pre-application assessments are continuing to be undertaken by the adult learning team. From 29 September 2017 until 10 November 2017 there have been 22 assessments carried out, of which 19 passed, 3 failed and none failed to attend. In relation to two separate Licensing Hearings Panels convened on 31 October 2017, the Licensing Unit Manager explained that the first for Polka, Parkhills Road, Bury, had presented an application to transfer the surrendered premises licence. Greater Manchester Police gave notice that the exceptional circumstances of the case are such that granting the application would undermine the crime prevention objective. -

Post Office Network Change Programme 2008

Manchester City Council Agenda Item 8 Executive 25 June 2008 MANCHESTER CITY COUNCIL REPORT FOR RESOLUTION REPORT TO THE EXECUTIVE DATE 25th JUNE 2008 SUBJECT POST OFFICE NETWORK CHANGE PROGRAMME 2008 REPORT OF THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE PURPOSE OF REPORT The purpose of this report is to brief Members on the proposed post office closures in Manchester and to set out our proposed programme of work in response to the consultation process. Attached to the report is the Area Plan for Greater Manchester and High Peak. RECOMMENDATIONS The Executive is recommended to: 1. Note the contents of the report; 2. Delegate authority to the Chief Executive and Deputy Leader to finalise Manchester City Council’s response to the Post Office Closure Consultation. ANNEX 1. Area Plan for Greater Manchester and High Peak FINANCIAL CONSEQUENCES FOR THE REVENUE BUDGET None FINANCIAL CONSEQUENCES FOR THE CAPTAL BUDGET None CONTACT OFFICERS Howard Bernstein Chief Executive 234 3006 [email protected] Sara Todd Head of Regeneration 234 3267 [email protected] Elaine Weinbren Policy Officer 234 3315 Manchester City Council Agenda Item 8 Executive 25 June 2008 [email protected] BACKGROUND DOCUMENTS Motion to Full Council 26th March 2008 Post Offices Report to Communities and Resources Overview and Scrutiny Committee on 5th February 2008 Post Office Network Change Programme 2008 Information Item to Resources and Governance Scrutiny Committee on 6th September 2007. Report to Executive 14th February 2007 ‘The Last Post Report’ by New Economics Foundation and Department for Trade and Industry (DTI) Consultation regarding the future of the Post Office Network. -

Thank You Mr Mayor for the Opportunity to Report to the Council the Latest Developments on Various Matters Relating to the Environment and Leisure Portfolio

ROCHDALE METROPOLITAN BOROUGH COUNCIL CABINET MEMBER REPORT TO THE COUNCIL REPORT OF THE CABINET MEMBER FOR ENVIRONMENT AND LEISURE TO THE MEETING OF THE COUNCIL ON 13 TH OCTOBER 2010 Thank you Mr Mayor for the opportunity to report to the Council the latest developments on various matters relating to the Environment and Leisure Portfolio. I would like to start my report by paying tribute to Peter Cunningham Peter started work for the authority 25 years ago in what was the Employment Projects Directorate managing the Community Programme. With the advent of Compulsory Competitive Tendering in 1988 he was appointed GroundCare Services Manager with Direct Services. For the last five years Peter has headed up Environmental Management Services. Having spoken with Peter I know that he is particularly pleased with the resurgence of the borough’s parks, culminating is seven green flags (plus one for Middleton Cemetery) and the fact that Rochdale was the only authority in the North West to make the Top Ten in the recent vote for the Nation’s Favourite Park competition with not one entry but two, Queens Park winning the competition and Hare Hill Park coming in third place. Under Peter’s stewardship we have also seen recycling rise to 33% and a dramatic increase in the cleanliness of our streets. I am sure that I speak for everybody at the council when I say that Peter will be sadly missed. He was a role model for other officers in that he was hard-working and cared passionately about what he was doing. I always found him to be a most pleasant, friendly and approachable officer with a good sense of humour and he – and the council – should be pleased with the achievements his conscientious approach produced. -

Heywood GI Plan Consultation Events, October 2008 to July 2010. Date Event

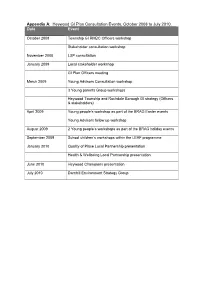

Appendix A : Heywood GI Plan Consultation Events, October 2008 to July 2010. Date Event October 2008 Township GI RMBC Officers workshop Stakeholder consultation workshop November 2008 LSP consultation January 2009 Local stakeholder workshop GI Plan Officers meeting March 2009 Young Advisors Consultation workshop 3 Young parents Group workshops Heywood Township and Rochdale Borough GI strategy (Officers & stakeholders) April 2009 Young people’s workshop as part of the BRAG Easter events Young Advisors follow up workshop August 2009 2 Young people’s workshops as part of the BRAG holiday events September 2009 School children’s workshops within the LEAF programme January 2010 Quality of Place Local Partnership presentation Health & Wellbeing Local Partnership presentation June 2010 Heywood Champions presentation July 2010 Darnhill Environment Strategy Group Appendix B : Public consultation on the Draft Heywood GI Plan, July 9 to 16 August 2010. Organi sation Service Area Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council Departments including: Environmental Management Planning & Regulation Performance & Transformation Strategic Housing Services Policy, Partnerships & Regeneration External Organisations & Stakeholders Bury MBC Strategic Planning Collins Landscapes Mowing Contractor, Darnhill Council for Voluntary Services Rochdale Centre Manager EDR Consulting Heywood Central Regeneration Area Forestry Commission Woodland Officer Environment Agency Planning & Climate Change Greater Manchester Police Heywood Neighbourhood Policing Team Groundwork Oldham