Mhioiz4canjiuseum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wild Bee Species Increase Tomato Production and Respond Differently to Surrounding Land Use in Northern California

BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION 133 (2006) 81– 87 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Wild bee species increase tomato production and respond differently to surrounding land use in Northern California Sarah S. Greenleaf*, Claire Kremen1 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Pollination provided by bees enhances the production of many crops. However, the contri- Received 11 December 2005 bution of wild bees remains unmeasured for many crops, and the effects of anthropogenic Received in revised form change on many bee species are unstudied. We experimentally investigated how pollina- 5 May 2006 tion by wild bees affects tomato production in northern California. We found that wild bees Accepted 16 May 2006 substantially increase the production of field-grown tomato, a crop generally considered Available online 24 July 2006 self-pollinating. Surveys of the bee community on 14 organic fields that varied in proximity to natural habitat showed that the primary bee visitors, Anthophora urbana Cresson and Keywords: Bombus vosnesenskii Radoszkowski, were affected differently by land management prac- Agro-ecosystem tices. B. vosnesenskii was found primarily on farms proximate to natural habitats, but nei- Crop pollination ther proximity to natural habitat nor tomato floral abundance, temperature, or year Ecosystem services explained variation in the visitation rates of A. urbana. Natural habitat appears to increase Bombus vosnesenskii B. vosnesenskii populations and should be preserved near farms. Additional research is Anthophora urbana needed to determine how to maintain A. urbana. Species-specific differences in depen- Habitat conservation dency on natural habitats underscore the importance of considering the natural histories of individual bee species when projecting population trends of pollinators and designing management plans for pollination services. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Bees and belonging: Pesticide detection for wild bees in California agriculture and sense of belonging for undergraduates in a mentorship program Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8z91q49s Author Ward, Laura True Publication Date 2020 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Bees and belonging: Pesticide detection for wild bees in California agriculture and sense of belonging for undergraduates in a mentorship program By Laura T Ward A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, Policy, and Management in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Nicholas J. Mills, Chair Professor Erica Bree Rosenblum Professor Eileen A. Lacey Fall 2020 Bees and belonging: Pesticide detection for wild bees in California agriculture and sense of belonging for undergraduates in a mentorship program © 2020 by Laura T Ward Abstract Bees and belonging: Pesticide detection for wild bees in California agriculture and sense of belonging for undergraduates in a mentorship program By Laura T Ward Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, Policy, and Management University of California, Berkeley Professor Nicholas J. Mills, Chair This dissertation combines two disparate subjects: bees and belonging. The first two chapters explore pesticide exposure for wild bees and honey bees visiting crop and non-crop plants in northern California agriculture. The final chapter utilizes surveys from a mentorship program as a case study to analyze sense of belonging among undergraduates. The first chapter of this dissertation explores pesticide exposure for wild bees and honey bees visiting sunflower crops. -

Apoidea: Andrenidae: Panurginae)

Contemporary distributions of Panurginus species and subspecies in Europe (Apoidea: Andrenidae: Panurginae) Sébastien Patiny Abstract The largest number of Old World Panurginus Nylander, 1848 species is distributed in the West- Palaearctic. The genus is absent in Africa and rather rare in the East-Palaearctic. Warncke (1972, 1987), who is the main author treating Palaearctic Panurginae in the last decades, subdivided Panurginus into a small number of species, including two principal taxa admitting for each a very large number of subspecies: Panurginus brullei (Lepeletier, 1841) and Panurginus montanus Giraud, 1861. Following recent works, the two latter are in fact complexes of closely related species. In the West-Palaearctic context, distributions of certain species implied in these complexes appear as very singular, distinct of mostly all other Panurginae ranges and highly interesting from a fundamental point of view. Based on a cartographic approach, the causes which influence (or have conditioned, in the past) the observed ranges of these species are discussed. Key words: Panurginae, biogeography, West-Palaearctic, speciation, glaciation. Introduction 1841) sensu lato are studied in the present paper. In the Old World Panurginae fauna, Panurginus The numerous particularities of their distribu- Nylander, 1848 is one of the only two genera tions are characterized and discussed here. The (with Melitturga Latreille, 1809) which are limits of these distributions were proposed and distributed in the entire Palaearctic region. The related to the contemporary and past develop- genera Camptopoeum Spinola, 1843 and Panur- ments which could have caused these ranges. gus Panzer, 1806 are also represented in the East- Palaearctic (in northern Thailand), but too few Catalogue of the old world species data are available for these genera to make them of Panurginus the subject of particular considerations. -

Anthophila List

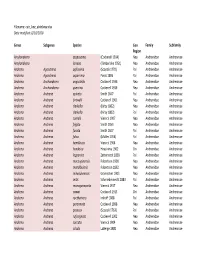

Filename: cuic_bee_database. -

1. Padil Species Factsheet Scientific Name: Common Name Image

1. PaDIL Species Factsheet Scientific Name: Panurginus ineptus Cockerell, 1922 (Hymenoptera: Andrenidae: Panurginae: Panurgini) Common Name Tribe Representative - Panurgini Live link: http://www.padil.gov.au/pollinators/Pest/Main/139784 Image Library Australian Pollinators Live link: http://www.padil.gov.au/pollinators/ Partners for Australian Pollinators image library Western Australian Museum https://museum.wa.gov.au/ South Australian Museum https://www.samuseum.sa.gov.au/ Australian Museum https://australian.museum/ Museums Victoria https://museumsvictoria.com.au/ 2. Species Information 2.1. Details Specimen Contact: Museum Victoria - [email protected] Author: Ken Walker Citation: Ken Walker (2010) Tribe Representative - Panurgini(Panurginus ineptus)Updated on 8/11/2010 Available online: PaDIL - http://www.padil.gov.au Image Use: Free for use under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY- NC 4.0) 2.2. URL Live link: http://www.padil.gov.au/pollinators/Pest/Main/139784 2.3. Facets Bio-Region: USA and Canada, Europe and Northern Asia Host Family: Not recorded Host Genera: Fresh Flowers Status: Exotic Species not in Australia Bio-Regions: Palaearctic, Nearctic Body Hair and Scopal location: Body hair relatively sparse, Tibia Episternal groove: Present but not extending below scrobal groove Wings: Submarginal cells - Three, Apex of marginal cell truncate or rounded Head - Structures: Two subantennal sutures below each antennal socket, Facial fovea present usually as a broad groove, Facial -

Hymenoptera, Apoidea)

>lhetian JMfuseum ox4tates PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK 24, N.Y. NUMBER 2 2 24 AUGUST I7, I 965 The Biology and Immature Stages of Melitturga clavicornis (Latreille) and of Sphecodes albilabris (Kirby) and the Recognition of the Oxaeidae at the Family Level (Hymenoptera, Apoidea) BYJEROME G. ROZEN, JR.' Michener (1944) divided the andrenid subfamily Panurginae into two tribes, the Panurgini and Melitturgini, with the latter containing the single Old World genus Melitturga. This genus was relegated to tribal status apparently on the grounds that the adults, unlike those of other panurgines, bear certain striking resemblances to the essentially Neo- tropical Oxaeinae of the same family. In 1951 Rozen showed that the male genitalia of Melitturga are unlike those of the Oxaeinae and are not only typical of those of the Panurginae in general but quite like those of the Camptopoeum-Panurgus-Panurginus-Epimethea complex within the sub- family. On the basis of this information, Michener (1954a) abandoned the idea that the genus Melitturga represents a distinct tribe of the Panur- ginae. Recently evidence in the form of the larva of Protoxaea gloriosa Fox (Rozen, 1965) suggested that the Oxaeinae were so unlike other Andreni- dae that they should be removed from the family unless some form inter- 1 Chairman and Associate Curator, Department of Entomology, the American Museum of Natural History. 2 AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES NO. 2224 mediate between the two subfamilies is found. In spite of the structure of the male genitalia, Melitturga is the only known possible intermediary. -

Identification of 37 Microsatellite Loci for Anthophora Plumipes (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Using Next Generation Sequencing and Their Utility in Related Species

Eur. J. Entomol. 109: 155–160, 2012 http://www.eje.cz/scripts/viewabstract.php?abstract=1692 ISSN 1210-5759 (print), 1802-8829 (online) Identification of 37 microsatellite loci for Anthophora plumipes (Hymenoptera: Apidae) using next generation sequencing and their utility in related species KATEěINA ýERNÁ and JAKUB STRAKA Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Charles University in Prague, Viniþná 7, 128 43 Praha 2, Czech Republic; e-mails: [email protected]; [email protected] Key words. Hymenoptera, Apidae, microsatellite development, Anthophora plumipes, 454 sequencing, Anthophorini Abstract. Novel microsatellite markers for the solitary bee, Anthophora plumipes, were identified and characterised using 454 GS-FLX Titanium pyrosequencing technology. Thirty seven loci were tested using fluorescently labelled primers on a sample of 20 females from Prague. The number of alleles ranged from 1 to 10 (with a mean of 4 alleles per locus), resulting in an observed hetero- zygosity ranging from 0.05 to 0.9 and an expected heterozygosity from 0.097 to 0.887. None of the loci showed a significant devia- tion from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and only two loci showed the significant presence of null alleles. No linkage between loci was detected. We further provide information on a single multiplex PCR consisting of 11 of the most polymorphic loci. This multi- plex approach provides an effective analytical tool for analysing genetic structure and carrying out parental analyses on Anthophora populations. Most of the 37 loci tested also showed robust amplification in five other Anthophora species (A. aestivalis, A. crinipes, A. plagiata, A. pubescens and A. quadrimaculata). -

The Foraging Preferences of the Hairy-Footed Flower Bee (Anthophora Plumipes (Pallas 1772) in a Surburban Garden

THE FORAGING PREFERENCES OF THE HAIRY-FOOTED FLOWER BEE (ANTHOPHORA PLUMIPES (PALLAS 1772) IN A SURBURBAN GARDEN Maggie Frankum, 3 Chapel Lane, Knighton, Leicester LE2 3WF PREAMBLE This paper is based on a project carried out as a requirement of a three-year Diploma in Applied Ecology at the University of Leicester (1997). The original report is extensively illustrated and stretches to 85 pages. This paper attempts to distill the main findings of the research. It is hoped that it will stimulate other entomologists in the county to carry out basic research literally on their own doorstep. INTRODUCTION In springtime, with the onset of warmer weather, the foraging activities of social bumblebees such as Bombus pratorum, B pascuorum, B hortorum, B terrestris and B lapidarius, are fairly commonplace in suburban gardens. The first big queens emerge from hibernation to establish their nests and produce new worker bees. However, there are other species of bees that are less noticeable until some particular behaviour pattern draws attention to them. One such early species is the hairy-footed flower bee, Anthophora plumipes (Pallas, 1772; Figure 1), striking in its sexual dimorphism. The golden-brown male has a distinct yellow face and fans of long bristles on the middle legs (hence its common name). The jet black female has orange pollen brushes on the hind legs. male female Figure 1: Anthophora plumipes They are hairy and look like small bumble bees with a body length of about 14mm (Proctor et al , 1996). However, they do differ as the eyes extend to the jaw without the usual cheek patches found in bumblebees (Chinery, 1972). -

Examining Native and Invasive Flower Preferences in Wild Bee Populations

Examining Native and Invasive Flower Preferences in Wild Bee Populations BIOS 35502-01: Practicum in Field Biology By Eileen C Reeves Advisor: Dr. Rose-Marie Muzika 2018 Abstract This experiment set out to determine if introduced and invasive flowers are less appealing to native pollinators, potentially contributing to the effects of habitat loss on these vulnerable insect populations. Invasive plants pose threats to native ecosystems by crowding out native plants and displacing native species. Wild bee populations face threats from habitat loss and fragmentation. To determine non- native flowers’ effects on wild bees, I observed plots of either native or introduced wildflowers and counted the number of visits made by different genera of bees. I found no significant preference for native or introduced flowers in five of the six genera observed. One genus, Lasioglossum sp. showed a significant preference for introduced flowers. Introduction Insect pollinators face a wide variety of threats, from habitat loss and fragmentation to pesticides to disease. The federal Pollinator Research Action Plan describes the threats facing pollinators and calls for increased research to protect these integral species. Native bees, the most effective pollinators of many native plants, are a vital part of their ecosystems. Determining specific land management strategies aimed at protecting both the native plants and the insects that feed on them can facilitate healthier ecosystems. An important aspect of land management is controlling invasive species. Invasive plants threaten native plant populations by crowding and outcompeting native plants for limited resources. In efforts to help bolster failing populations of native pollinators, providing land for wildflowers to colonize may not be sufficient: successional native plants may be required. -

A Catalogue of the Family Andrenidae (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of Eritrea

Linzer biol. Beitr. 50/1 655-659 27.7.2018 A catalogue of the family Andrenidae (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of Eritrea Michael MADL A b s t r a c t : In Eritrea the family Andrenidae is represented by two species of the genus Andrena FABRICIUS, 1775 (subfamily Andreninae) and one species each oft he genera Borgatomelissa PATINY, 2000 and Meliturgula FRIESE, 1903 (both subfamily Panurginae). The record of the genus Andrena is doubtful. K e y w o r d s : Andrenidae, Andreninae, Andrena, Panurginae, Borgatomelissa, Meliturgula, Eritrea. Introduction In the Afrotropical region the family Andrenidae is represented by more than 30 species (EARDLEY & URBAN 2010). The Eritrean fauna of of the family Andrenidae is poorly known. The knowledge is based on the material collected by J.K. Lord in 1869 and by P. Magretti in 1900. No further material is known. Up to date two species each of the subfamilies Andreninae (genus Andrena FABRICIUS, 1775) and Panurginae (genera Borgatomelissa PATINY, 2000 and Meliturgula FRIESE, 1903) have been recorded from Eritrea. Abbreviations Afr. reg. .................................. Afrotropical region biogeogr. ......................................... biogeography biol. .......................................................... biology cat. ......................................................... catalogue descr. ................................................... description fig. (figs) ....................................... figure (figures) syn. ......................................................... synonym tab. -

Phylogeny and Classification of the Parasitic Bee Tribe Epeolini (Hymenoptera: Apidae, Nomadinae)^

Ac Scientific Papers Natural History Museum The University of Kansas 06 October 2004 Number 33:1-51 Phylogeny and classification of the parasitic bee tribe Epeolini (Hymenoptera: Apidae, Nomadinae)^ By Molly G. Rightmyer y\CZ Division of E)itoiiiologi/, Nntuinl History Museiiui mid Biodizvrsity Rcsenrch Center, jV^Ar^^ and Eiitomology Progrniii, Department of Ecology nnd Evolutionary Biology, The Unii>ersity of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, 66045-7523 CONTENTS ^AB'"^^?Sy ABSTRACT 2 lJHIVE^^^ ' INTRODUCTION 2 Acknowledgments 2 HISTORICAL REVIEW 3 METHODS AND MATERIALS 5 MORPHOLOGY 7 PsEUDOPYGiDiAL Area 7 Sting Apparatus 7 Male Internal Sclerites 11 PHYLOGENETIC RESULTS 11 SYSTEMATICS 13 Tribe Epeolini Robertson 13 Subtribe Odyneropsina Handlirsch new status 14 Genus Odyneropsis Schrottky 14 Subgenus Odyneropsis Schrottky new status 15 Subgenus Parammobates Friese new status 15 Rhogepeolina new subtribe 15 Genus Rhogepeolus Moure 15 Rhogepeolina + (Epeolina + Thalestriina) 16 Epeolina + Thalestriina 16 Subtribe Epeolina Robertson new status 16 Genus Epeolus Latreille 16 'Contribution No. 3397 of the Division of Entomology, Natural History Museum and Biodiversity Research Center, University of Kansas. Natural ISSN No. 1094-0782 © History Museum, The University of Kansas _ . «i„,, I <*»ro»V Ernst K'ayr Li^^rary Zoology Museum of Comparawe Harvard University Ac Scientific Papers Natural History Museum The University of Kansas 06 October 2004 NumLx-r 33:1-51 Phylogeny and classification of the parasitic bee tribe Epeolini (Hymenoptera: Apidae, Nomadinae)' -

Scenarios for Pollinator Habitat at Denver International Airport

Scenarios for Pollinator Habitat at Denver International Airport by Tiantong Gu (Landscape Architecture) Xuan Jin (Landscape Architecture) Jiayang Li (Landscape Architecture) Annemarie McDonald (Conservation Ecology) Chang Ni (Conservation Ecology) Client: Sasaki Adviser: Professor Joan Nassauer Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of Master of Landscape Architecture and Master of Natural Resources and Environment at the University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability April 17th 2018 Acknowledgments We would like to thank our adviser, Joan Nassauer, for her patience and thoughtful advice throughout the course of this project. We would also like to thank Tao Zhang, our client liaison, for his critiques and suggestions. We are grateful to the staff at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge, especially Tom Wall, and the Applewood Seed Company for their assistance in the planting designs in this project. Funding for our project was provided by University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability. Finally, we would like to thank all of our families for their support and encouragement during this process. Table of Contents Contents Habitat Corridor Scenarios 71 Scenario Performance Hypothesis 71 Abstract 7 Development Pattern 80 Landscape Element Typologies 82 Introduction 8 Reserach Goals 12 Scenario Assessment 87 InVEST Crop Pollination Model 87 Literature Review 13 Pollinator Guild Table 87 The Shortgrass Prairie Ecosystem 13 Biophysical Table 89 Airport Impacts on