A Layman's Guide to M-Theory1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Al-Nahl Volume 13 Number 3

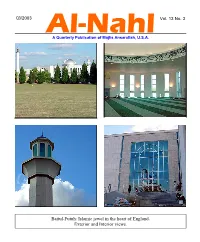

Q3/2003 Vol. 13 No. 3 Al-Nahl A Quarterly Publication of Majlis Ansarullah, U.S.A. Baitul-Futuh: Islamic jewel in the heart of England. Exterior and Interior views. Special Issue of the Al-Nahl on the Life of Hadrat Dr. Mufti Muhammad Sadiq, radiyallahu ‘anhu. 60 pages, $2. Special Issue on Dr. Abdus Salam. 220 pages, 42 color and B&W pictures, $3. Ansar Ansar (Ansarullah News) is published monthly by Majlis Ansarullah U.S.A. and is sent free of charge to all Ansar in the U.S. Ordering Information: Send a check or money order in the indicated amount along with your order to Chaudhary Mushtaq Ahmad, 15000 Good Hope Rd, Silver Spring, MD 20905. Price includes shipping and handling within the continental U.S. Conditions of Bai‘at, Pocket-Size Edition Majlis Ansarullah, U.S.A. has published the ten conditions of initiation into the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in pocket size brochure. Contact your local officials for a free copy or write to Ansar Publications, 15000 Good Hope Rd, Silver Spring MD 20905. Razzaq and Farida A story for children written by Dr. Yusef A. Lateef. Children and new Muslims, all can read and enjoy this story. It makes a great gift for the children of Ahmadi, Non-Ahmadi and Non- Muslim relatives, friends and acquaintances. The book contains colorful drawings. Please send $1.50 per copy to Chaudhary Mushtaq Ahmad, 15000 Good Hope Rd, Silver Spring, MD 20905 with your mailing address and phone number. Majlis Ansarullah U.S.A. will pay the postage and handling within the continental U.S. -

Rutherford's Nuclear World: the Story of the Discovery of the Nuc

Rutherford's Nuclear World: The Story of the Discovery of the Nuc... http://www.aip.org/history/exhibits/rutherford/sections/atop-physic... HOME SECTIONS CREDITS EXHIBIT HALL ABOUT US rutherford's explore the atom learn more more history of learn about aip's nuclear world with rutherford about this site physics exhibits history programs Atop the Physics Wave ShareShareShareShareShareMore 9 RUTHERFORD BACK IN CAMBRIDGE, 1919–1937 Sections ← Prev 1 2 3 4 5 Next → In 1962, John Cockcroft (1897–1967) reflected back on the “Miraculous Year” ( Annus mirabilis ) of 1932 in the Cavendish Laboratory: “One month it was the neutron, another month the transmutation of the light elements; in another the creation of radiation of matter in the form of pairs of positive and negative electrons was made visible to us by Professor Blackett's cloud chamber, with its tracks curled some to the left and some to the right by powerful magnetic fields.” Rutherford reigned over the Cavendish Lab from 1919 until his death in 1937. The Cavendish Lab in the 1920s and 30s is often cited as the beginning of modern “big science.” Dozens of researchers worked in teams on interrelated problems. Yet much of the work there used simple, inexpensive devices — the sort of thing Rutherford is famous for. And the lab had many competitors: in Paris, Berlin, and even in the U.S. Rutherford became Cavendish Professor and director of the Cavendish Laboratory in 1919, following the It is tempting to simplify a complicated story. Rutherford directed the Cavendish Lab footsteps of J.J. Thomson. Rutherford died in 1937, having led a first wave of discovery of the atom. -

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy And

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy and Anglo-American Relations, 1939 – 1958 Submitted by: Geoffrey Charles Mallett Skinner to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, July 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) ……………………………………………………………………………… 1 Abstract There was no special governmental partnership between Britain and America during the Second World War in atomic affairs. A recalibration is required that updates and amends the existing historiography in this respect. The wartime atomic relations of those countries were cooperative at the level of science and resources, but rarely that of the state. As soon as it became apparent that fission weaponry would be the main basis of future military power, America decided to gain exclusive control over the weapon. Britain could not replicate American resources and no assistance was offered to it by its conventional ally. America then created its own, closed, nuclear system and well before the 1946 Atomic Energy Act, the event which is typically seen by historians as the explanation of the fracturing of wartime atomic relations. Immediately after 1945 there was insufficient systemic force to create change in the consistent American policy of atomic monopoly. As fusion bombs introduced a new magnitude of risk, and as the nuclear world expanded and deepened, the systemic pressures grew. -

Urdu Syllabus

TUMKUR UINIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF URDU'. SYLLABUS AND TEXT BOOKS UNDER CBCS SCHEME LANGUAGE URDU lst Semester B.A./llsc/B.com/BBM/BCA lffect From 20!6-tz lst Semester B.A. Svllabus: Texts: I' 1. Collection of Prose and Poetry Urdu Language Text Book for First Semister B.A.: Edited by: URDU BOS (UG) (Printed and Published by prasaranga, Bangarore university, Bangalore) 2. Non-detail : Selected 4 Chapters From Text Book Reference Books: 1. Yadgaray Hali Saleha Aabid Hussain 2. lqbal Ka Narang QopiChandt 'i Page 1 z' i!. .F}*$T g_€.9f.*g.,,,E B'A BE$BEE CBU R$E Eenlcprqrerlh'ed:.Ufifi9 TFXT B €KeCn e,A I SEMESTER, : ,1 1;5:. -ll-=-- -i- - 1. padiye Gar Bcemar. 'M,tr*hf ag:A.hmgd-$tib.uf i 1.,gglrEdnre:a E*yl{arsfrt$ay Khwaja Hasan Nizarni 3" M_ugalrnanen Ki GurashthaTaleem Shibll Nomani +. lfilopatra N+y,Ek Moti €hola Sclence Ki Duniya : 5. g,€land:|4i$ ..- Manarir,Aashiq flarganvi PelfTR.Y i X., Hazrathfsmail Ki Viladat .FJafeez,J*lan*ari Naath 2. Hsli Mir.*e6halib 3. lqbal 4. T*j &Iahat 5*-e-ubipe.t{i Saher Ludhianawi ,,, lqbal, Amjad, Akbar {Z Eaehf 6g'**e€{F} i ': 1.. 6azaf W*& 2;1 ' 66;*; JaB:Flis,qf'*kfiit" 4., : €*itrl $hmed Fara:, 4. €azgl Firaq ,5; *- ,Elajrooh 6, Gqzal Shahqr..Y.aar' V. Gazal tiiarnsp{.4i1sruu ' 8. Gaal Narir Kqgrnt NG$I.SE.f*IL.: 1- : .*akF*!h*s ,&ri*an Ch*lrdar; 3. $alartrf,;oat &jendar.Sixgir.Ee t 3-, llfar*€,Ffate Tariq.€-hil*ari 4',,&alandar t'- €hig*lrl*tn:Ftyder' Ah*|.,9 . -

Patrick Blackett: Sailor, Scientist, Socialist, Chris Eldridge

Naval War College Review Volume 57 Article 31 Number 1 Winter 2004 Patrick Blackett: Sailor, Scientist, Socialist, Chris Eldridge Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Eldridge, Chris (2004) "Patrick Blackett: Sailor, Scientist, Socialist,," Naval War College Review: Vol. 57 : No. 1 , Article 31. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol57/iss1/31 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 156 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE REVIEW Eldridge: Patrick Blackett: Sailor, Scientist, Socialist, understanding with the Soviet Union (a he was the heart and soul of the Cold position favored by some influential War military-academic-industrial com- opinions in the United States) nor to cre- plex. In this book, sixteen authors at- ate trouble for the French government, tempt to shed light on Blackett’s role in seemingly both dependent on and threat- that story. The collection includes pa- ened by the French Communist Party. pers presented at a 1998 conference The Soviet-menace card was played on commemorating Blackett at Cambridge several occasions in the unfolding de- University, as well as other recent writ- bate, but in general it was subordinated ings about him. to more abstract arguments of enlight- Not surprisingly, the compendium of- ened self-interest. Moreover, it was fers a range of perspectives on events clear to many in the administration that and issues with which Blackett was as- too great an emphasis on the immi- sociated, rather than a comprehensive nence of war with Russia would scuttle examination of his life and work. -

Appendix E Nobel Prizes in Nuclear Science

Nuclear Science—A Guide to the Nuclear Science Wall Chart ©2018 Contemporary Physics Education Project (CPEP) Appendix E Nobel Prizes in Nuclear Science Many Nobel Prizes have been awarded for nuclear research and instrumentation. The field has spun off: particle physics, nuclear astrophysics, nuclear power reactors, nuclear medicine, and nuclear weapons. Understanding how the nucleus works and applying that knowledge to technology has been one of the most significant accomplishments of twentieth century scientific research. Each prize was awarded for physics unless otherwise noted. Name(s) Discovery Year Henri Becquerel, Pierre Discovered spontaneous radioactivity 1903 Curie, and Marie Curie Ernest Rutherford Work on the disintegration of the elements and 1908 chemistry of radioactive elements (chem) Marie Curie Discovery of radium and polonium 1911 (chem) Frederick Soddy Work on chemistry of radioactive substances 1921 including the origin and nature of radioactive (chem) isotopes Francis Aston Discovery of isotopes in many non-radioactive 1922 elements, also enunciated the whole-number rule of (chem) atomic masses Charles Wilson Development of the cloud chamber for detecting 1927 charged particles Harold Urey Discovery of heavy hydrogen (deuterium) 1934 (chem) Frederic Joliot and Synthesis of several new radioactive elements 1935 Irene Joliot-Curie (chem) James Chadwick Discovery of the neutron 1935 Carl David Anderson Discovery of the positron 1936 Enrico Fermi New radioactive elements produced by neutron 1938 irradiation Ernest Lawrence -

![Arxiv:1211.4061V3 [Physics.Hist-Ph] 8 Feb 2013](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9997/arxiv-1211-4061v3-physics-hist-ph-8-feb-2013-949997.webp)

Arxiv:1211.4061V3 [Physics.Hist-Ph] 8 Feb 2013

From cosmic ray physics to cosmic ray astronomy: Bruno Rossi and the opening of new windows on the universe Luisa Bonolis Via Cavalese 13 – 00135 Rome, Italy [email protected] Abstract Bruno Rossi is considered one of the fathers of modern physics, being also a pioneer in virtually every aspect of what is today called high-energy astrophysics. At the beginning of 1930s he was the pioneer of cosmic ray research in Italy, and, as one of the leading actors in the study of the nature and behavior of the cosmic radiation, he witnessed the birth of particle physics and was one of the main investigators in this fields for many years. While cosmic ray physics moved more and more towards astrophysics, Rossi continued to be one of the inspirers of this line of research. When outer space became a reality, he did not hesitate to leap into this new scientific dimension. Rossi’s intuition on the importance of exploiting new technological windows to look at the universe with new eyes, is a fundamental key to understand the profound unity which guided his scientific research path up to its culminating moments at the beginning of 1960s, when his group at MIT performed the first in situ measurements of the density, speed and direction of the solar wind at the boundary of Earth’s magnetosphere, and when he promoted the search for extra-solar sources of X rays. A visionary idea which eventually led to the breakthrough experiment which discovered Scorpius X-1 in 1962, and inaugurated X-ray astronomy. -

The Creation of the International Centre for Theoretical Physics in Trieste

Alexis De Greiff The tale of two peripheries The Tale of Two Peripheries: The Creation of the International Centre for Theoretical Physics in Trieste Publicado con cambios menores en Historical Studies of Physical and Biological Sciences (Special Issue, Alexis De Greiff y David Kaiser, eds.) Vol. 33, Part 1 (2002), pp. 33-60. Alexis De Greiff* Abstract: This paper can be seen in the intersection between history of 20th-century physics, diplomatic history and international relations of science. In this work I analyze the dynamics of the negotiations to create the International Centre for Theoretical Physics, which took place between 1960 and 1963 at the International Atomic Energy Agency. In contrast to previous studies on the creation of international scientific institutions, I pay special attention to the active role played by scientists, politicians and intellectuals from the host-city, Trieste (Italy). Further, I spell out the historical circumstances that allowed this group of local actors to become key figures in the establishment of the Centre. I discuss in detail their interests as well as the political and scientific environment that eventually catalysed the diplomatic efforts of the Trieste elite. The present paper is also concerned with the strategies adopted by the advocates of the idea to confront the hostility of delegations from several industrialized countries, the Soviet Union and India. A frontier is a strip which divides and links, a sour gash like a wound which heals with difficulty, a no-man’s land, a mixed territory, whose inhabitants often feel that they do not belong to any clearly-defined country, or at least they do not belong to any country with that obvious certainty with which one usually identifies with ones native land. -

PRINT CULTURE and LEFT-WING RADICALISM in LAHORE, PAKISTAN, C.1947-1971

PRINT CULTURE AND LEFT-WING RADICALISM IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN, c.1947-1971 Irfan Waheed Usmani (M.Phil, History, University of Punjab, Lahore) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my original work and it has been written by me in its entirety. I have duly acknowledged all the sources of information which have been used in the thesis. This thesis has also not been submitted for any degree in any university previously. _________________________________ Irfan Waheed Usmani 21 August 2015 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First I would like to thank God Almighty for enabling me to pursue my higher education and enabling me to finish this project. At the very outset I would like to express deepest gratitude and thanks to my supervisor, Dr. Gyanesh Kudaisya, who provided constant support and guidance to this doctoral project. His depth of knowledge on history and related concepts guided me in appropriate direction. His interventions were both timely and meaningful, contributing towards my own understanding of interrelated issues and the subject on one hand, and on the other hand, injecting my doctoral journey with immense vigour and spirit. Without his valuable guidance, support, understanding approach, wisdom and encouragement this thesis would not have been possible. His role as a guide has brought real improvements in my approach as researcher and I cannot measure his contributions in words. I must acknowledge that I owe all the responsibility of gaps and mistakes in my work. I am thankful to his wife Prof. -

Mathematics People, Volume 51, Number 11

Mathematics People bestowed by the U.S. government on outstanding young Bjorken and Callan Awarded scientists, mathematicians, and engineers who are in the 2004 Dirac Medals early stages of establishing their independent research careers. The 2004 Dirac Medals of the Abdus Salam International Three scholars who work in the mathematical sciences Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) have been awarded were honored for 2003. They are KONSTANTINA TRIVISA, Uni- to JAMES D. BJORKEN of Stanford University and CURTIS G. versity of Maryland, College Park; RAVI VAKIL, Stanford Uni- CALLAN of Princeton University for their work in the use of versity; and HARRY DANKOWICZ, Virginia Polytechnic Institute deep inelastic scattering for shedding light on the nature and State University. of strong interactions. The recipients were selected from nominations made The award citation reads: “Bjorken was the first to re- by eight participating federal agencies. Each awardee re- alize the importance of deep inelastic scattering and the ceives a five-year grant ranging from $400,000 to nearly first to understand the scaling of cross sections, an insight $1 million to further his or her research and educational that ultimately bore his name—the Bjorken scaling of efforts. cross sections. Callan, together with Kurt Symanzik (now deceased), reinvented the perturbative renormalization —From an NSF announcement group (in a form that now bears the name Callan-Symanzik equations) and recognized these groups as measures of scale invariance anomalies. Callan has applied these tech- Prizes of the Académie des niques to analyses of deep inelastic scattering and has made substantial contributions to particle physics and, more Sciences recently, string theory.” The ICTP awarded its first Dirac Medal in 1985. -

Bangladesh: Human Rights Report 2015

BANGLADESH: HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT 2015 Odhikar Report 1 Contents Odhikar Report .................................................................................................................................. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................... 4 Detailed Report ............................................................................................................................... 12 A. Political Situation ....................................................................................................................... 13 On average, 16 persons were killed in political violence every month .......................................... 13 Examples of political violence ..................................................................................................... 14 B. Elections ..................................................................................................................................... 17 City Corporation Elections 2015 .................................................................................................. 17 By-election in Dohar Upazila ....................................................................................................... 18 Municipality Elections 2015 ........................................................................................................ 18 Pre-election violence .................................................................................................................. -

Arabic Books Published in India an Annotated Bibliography

ARABIC BOOKS PUBLISHED IN INDIA AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF LIBRARY SCIENCE 1986-86 BY ISHTIYAQUE AHMAD Roll No, 85-M. Lib. Sc.-02 Enrolment No. S-2247 Under the Supervision of Mr. AL-MUZAFFAR KHAN READER DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH 1986 ,. J^a-175 DS975 SJO- my. SUvienJU ACKNOWLEDGEMENT It is not possible for me to thank adequately prof, M.H. Rizvi/ University Librarian and Chairman Department of Library Science. His patronage indeed had always been a source of inspiration, I stand deeply indebted to my supervisor, Mr. Al- Muzaffar Khan, Reader, Department of Library Science without whom invaluable suggestions and worthy advice, I would have never been able to complete the work. Throughout my stay in the department he obliged me by unsparing help and encouragement. I shall be failing in my daties if I do not record the names of Dr. Hamid All Khan, Reader, Department of Arabic and Mr, Z.H. Zuberi, P.A., Library of Engg. College with gratitude for their co-operation and guidance at the moment I needed most, I must also thank my friends M/s Ziaullah Siddiqui and Faizan Ahmad, Research Scholars, Arabic Deptt., who boosted up my morals in the course of wtiting this dis sertation. My sincere thanks are also due to S. Viqar Husain who typed this manuscript. ALIGARH ISHl'ltAQUISHTIYAQUE AAHMA D METHODOLOBY The present work is placed in the form of annotation, the significant Arabic literature published in India, The annotation of 251 books have been presented.