Chapter 11 – Shell Artifacts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Raman Investigations to Identify Corallium Rubrum in Iron Age Jewelry and Ornaments

minerals Article Raman Investigations to Identify Corallium rubrum in Iron Age Jewelry and Ornaments Sebastian Fürst 1,†, Katharina Müller 2,†, Liliana Gianni 2,†, Céline Paris 3,†, Ludovic Bellot-Gurlet 3,†, Christopher F.E. Pare 1,† and Ina Reiche 2,4,†,* 1 Vor- und Frühgeschichtliche Archäologie, Institut für Altertumswissenschaften, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Schillerstraße 11, Mainz 55116, Germany; [email protected] (S.F.); [email protected] (C.F.E.P.) 2 Sorbonne Universités, UPMC Université Paris 06, CNRS, UMR 8220, Laboratoire d‘archéologie moléculaire et structurale (LAMS), 4 Place Jussieu, 75005 Paris, France; [email protected] (K.M.); [email protected] (L.G.) 3 Sorbonne Universités, UPMC Université Paris 06, CNRS, UMR 8233, De la molécule au nano-objets: réactivité, interactions et spectroscopies (MONARIS), 4 Place Jussieu, 75005 Paris, France; [email protected] (C.P.); [email protected] (L.B.-G.) 4 Rathgen-Forschungslabor, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin-Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Schloßstraße 1 a, Berlin 14059, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +49-30-2664-27101 † These authors contributed equally to this work. Academic Editor: Steve Weiner Received: 31 December 2015; Accepted: 1 June 2016; Published: 15 June 2016 Abstract: During the Central European Iron Age, more specifically between 600 and 100 BC, red precious corals (Corallium rubrum) became very popular in many regions, often associated with the so-called (early) Celts. Red corals are ideally suited to investigate several key questions of Iron Age research, like trade patterns or social and economic structures. While it is fairly easy to distinguish modern C. -

A Quick Guide to Cooking with Ausab Abalone in Brine

A Quick Guide to Cooking With Ausab Abalone in Brine Ausab Canned Abalone is a versatile product that requires minimal effort to create the perfect meal at home. The abalone is completely cleaned and cooked, and ready to eat. With a unique umami flavor, it can be used in many different ways. The meat is smooth and tender, and the perfect balance between sweet and salty. Ensure the canned abalone is stored in a well ventilated, cool place out of direct sunlight. How to Prepare the Abalone The abalone is canned, ready to eat with mouth attached. To preserve it’s tender texture, it is best to use the abalone when just heated through. This can be achieved by using the abalone at the end of cooking, or slowly heated in the can. To safely heat the abalone in it’s can follow these steps: 1. Leave the can unopened and remove all labels. 2. Place the can into a pot of water so that it is fully submerged and is horizontal. 3. Bring the water to a gentle simmer and leave submerged for 15 – 20 minutes. 4. Remove the pot from the heat and wait for the water to cool before carefully lifting the can out of the water with large tongs. 5. Open the can once it is cool enough to handle. 6. The abalone can be served whole or sliced thinly. Abalone Recipes Ausab Canned Abalone can be pan fried, used in soups or grilled. Teriyaki Abalone Serves 4 1 x Ausab Canned Abalone in Brine 250ml Light Soy Sauce 200ml Mirin 200ml Sake 60g Sugar 1. -

CHEMICAL STUDIES on the MEAT of ABALONE (Haliotis Discus Hannai INO)-Ⅰ

Title CHEMICAL STUDIES ON THE MEAT OF ABALONE (Haliotis discus hannai INO)-Ⅰ Author(s) TANIKAWA, Eiichi; YAMASHITA, Jiro Citation 北海道大學水産學部研究彙報, 12(3), 210-238 Issue Date 1961-11 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/23140 Type bulletin (article) File Information 12(3)_P210-238.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP CHEMICAL STUDIES ON THE MEAT OF ABALONE (Haliotis discus hannai INo)-I Eiichi TANIKAWA and Jiro YAMASHITA* Faculty of Fisheries, Hokkaido University There are about 90 existing species of abalones (Haliotis) in the world, of which the distribution is wide, in the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian Oceans. Among the habitats, especially the coasts along Japan, the Pacific coast of the U.S.A. and coasts along Australia have many species and large production. In Japan from ancient times abalones have been used as food. Japanese, as well as American, abalones are famous for their large size. Among abalones, H. gigantea (" Madaka-awabi "), H. gigantea sieboldi (" Megai-awabi "), H. gigantea discus (" Kuro-awabi") and H. discus hannai (" Ezo-awabi") are important in commerce. Abalone is prepared as raw fresh meat (" Sashimi") or is cooked after cut ting it from the shell and trimming the visceral mass and then mantle fringe from the large central muscle which is then cut transversely into slices. These small steaks may be served at table as raw fresh meat (" Sashimi") or may be fried, stewed, or minced and made into chowder. A large proportion of the abalones harvested in Japan are prepared as cooked, dried and smoked products for export to China. -

“Charlie Chaplin” Figures of the Maya Lowlands

RITUAL USE OF THE HUMAN FORM: A CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF THE “CHARLIE CHAPLIN” FIGURES OF THE MAYA LOWLANDS by LISA M. LOMITOLA B.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2012 ©2012 Lisa M. Lomitola ii ABSTRACT Small anthropomorphic figures, most often referred to as “Charlie Chaplins,” appear in ritual deposits throughout the ancient Maya sites of Belize during the late Preclassic and Early Classic Periods and later, throughout the Petén region of Guatemala. Often these figures appear within similar cache assemblages and are carved from “exotic” materials such as shell or jade. This thesis examines the contexts in which these figures appear and considers the wider implications for commonly held ritual practices throughout the Maya lowlands during the Classic Period and the similarities between “Charlie Chaplin” figures and anthropomorphic figures found in ritual contexts outside of the Maya area. iii Dedicated to Corbin and Maya Lomitola iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Drs. Arlen and Diane Chase for the many opportunities they have given me both in the field and within the University of Central Florida. Their encouragement and guidance made this research possible. My experiences at the site of Caracol, Belize have instilled a love for archaeology in me that will last a lifetime. Thank you Dr. Barber for the advice and continual positivity; your passion and joy of archaeology inspires me. In addition, James Crandall and Jorge Garcia, thank you for your feedback, patience, and support; your friendship and experience are invaluable. -

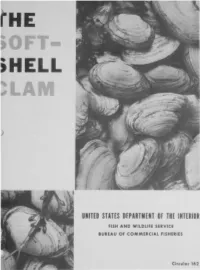

Circular 162. the Soft-Shell Clam

HE OFT iHELL 'LAM UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT 8F THE INTERIOR FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE BUREAU OF COMMERCIAL FISHERIES Circular 162 CONTENTS Page 1 Intr oduc tion. • • • . 2 Natural history • . ~ . 2 Distribution. 3 Taxonomy. · . Anatomy. • • • •• . · . 3 4 Life cycle. • • • • • . • •• Predators, diseases, and parasites . 7 Fishery - methods and management .•••.••• • 9 New England area. • • • • • . • • • • • . .. 9 Chesapeake area . ........... 1 1 Special problem s of paralytic shellfish poisoning and pollution . .............. 13 Summary . .... 14 Acknowledgment s •••• · . 14 Selected bibliography •••••• 15 ABSTRACT Describes the soft- shell cla.1n industry of the Atlantic coast; reviewing past and present economic importance, fishery methods, fishery management programs, and special problems associated with shellfish culture and marketing. Provides a summary of soft- shell clam natural history in- eluding distribution, taxonomy, anatomy, and life cycle. l THE SOFT -SHELL CLAM by Robert W. Hanks Bureau of Commercial Fisheries Biological Labor ator y U.S. Fish and Wildlife Serv i c e Boothbay Harbor, Maine INTRODUCTION for s a lted c l a m s used as bait by cod fishermen on t he G r and Bank. For the next The soft-shell clam, Myaarenaria L., has 2 5 years this was the most important outlet played an important role in the history and for cla ms a nd was a sour ce of wealth to economy of the eastern coast of our country . some coastal communities . Many of the Long before the first explorers reached digg ers e a rne d up t o $10 per day in this our shores, clams were important in the busin ess during October to March, when diet of some American Indian tribes. -

The Significance of Copper Bells in the Maya Lowlands from Their

The significance of Copper bells in the Maya Lowlands On the cover: 12 bells unearthed at Lamanai, including complete, flattened and miscast specimens. From Simmons and Shugar 2013: 141 The significance of Copper bells in the Maya Lowlands - from their appearance in the Late Terminal Classic period to the current day - Arthur Heimann Master Thesis S2468077 Prof. Dr. P.A.I.H. Degryse Archaeology of the Americas Leiden University, Faculty of Archaeology (1084TCTY-F-1920ARCH) Leiden, 16/12/2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 5 1.1. Subject of The Thesis ................................................................................................................... 6 1.2. Research Question........................................................................................................................ 7 2. MAYA SOCIETY ........................................................................................................................... 10 2.1. Maya Geography.......................................................................................................................... 10 2.2. Maya Chronology ........................................................................................................................ 13 2.2.1. Preclassic ............................................................................................................................................................. 13 2.2.2. -

The Shell Matrix of the European Thorny Oyster, Spondylus Gaederopus: Microstructural and Molecular Characterization

The shell matrix of the european thorny oyster, Spondylus gaederopus: microstructural and molecular characterization. Jorune Sakalauskaite, Laurent Plasseraud, Jérôme Thomas, Marie Alberic, Mathieu Thoury, Jonathan Perrin, Frédéric Jamme, Cédric Broussard, Beatrice Demarchi, Frédéric Marin To cite this version: Jorune Sakalauskaite, Laurent Plasseraud, Jérôme Thomas, Marie Alberic, Mathieu Thoury, et al.. The shell matrix of the european thorny oyster, Spondylus gaederopus: microstructural and molecular characterization.. Journal of Structural Biology, Elsevier, 2020, 211 (1), pp.107497. 10.1016/j.jsb.2020.107497. hal-02906399 HAL Id: hal-02906399 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02906399 Submitted on 17 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The shell matrix of the European thorny oyster, Spondylus gaederopus: microstructural and molecular characterization List of authors: Jorune Sakalauskaite1,2, Laurent Plasseraud3, Jérôme Thomas2, Marie Albéric4, Mathieu Thoury5, Jonathan Perrin6, Frédéric Jamme6, Cédric Broussard7, Beatrice Demarchi1, Frédéric Marin2 Affiliations 1. Department of Life Sciences and Systems Biology, University of Turin, Via Accademia Albertina 13, 10123 Turin, Italy; 2. Biogeosciences, UMR CNRS 6282, University of Burgundy-Franche-Comté, 6 Boulevard Gabriel, 21000 Dijon, France. 3. Institute of Molecular Chemistry, ICMUB UMR CNRS 6302, University of Burgundy- Franche-Comté, 9 Avenue Alain Savary, 21000 Dijon, France. -

Spondylus Ornaments in the Mortuary Zone at Neolithic Vukovar on the Middle Danube

J. CHAPMAN, B. GAYDARSKA, J. BALEN: Spondylus ornaments..., VAMZ, 3. s., XLV (2012) 191 JOHN CHAPMAN Durham University Department of Archaeology Durham DH1 3LE, UK [email protected] BISSERKA GAYDARSKA Durham University Department of Archaeology Durham DH1 3LE, UK [email protected] JACQUELINE BALEN Archaeological museum in Zagreb Trg Nikole Šubića Zrinskog 19 HR-10000 Zagreb, Croatia [email protected] SPONDYLUS ORNAMENTS IN THE MORTUARY ZONE AT NEOLITHIC VUKOVAR ON THE MIDDLE DANUBE UDK: 903.25-035.56(497.5 Vukovar)»634« Izvorni znanstveni rad The AD 19th century finding of two graves with rich Spondylus shell ornaments in the town of Vukovar, Eastern Croatia, is here re-published with the aim of using the artifact biographical data embodied in the ornaments to assist in the determination of the temporal and spatial relationships of the artifacts with other Spondylus finds in the Carpathian Basin and the Balkans. Key words: Spondylus gaederopus; exchange; Danube; Neolithic; Vukovar; burials; artifact biography Ključne riječi: Spondylus gaederopus, razmjena, Dunav, neolitik, Vukovar, grobovi, biografija nalaza INTRODUCT I ON The opportunity to make a contribution to the Festschrift of a much-respected colleague – Ivan Mirnik – coincided with a 2011 research visit of two of the authors (JC and BG) to the museum now directed by the third (JB). Part of the new prehistory display consisted of two fascinating groups of Spondylus artifacts –two grave groups deriving from Vukovar. 192 J. CHAPMAN, B. GAYDARSKA, J. BALEN: Spondylus ornaments..., VAMZ, 3. s., XLV (2012) The date given in the exhibition to the group of Spondylus finds was Bronze Age! Since there has been little recent research on the Spondylus finds from Eastern Croatia, the authors decided to re-publish the find in Ivan’s Festschrift. -

Shells Shells Are the Remains of a Group of Animals Called Molluscs

Inspire - Educate – Showcase Shells Shells are the remains of a group of animals called molluscs. Bivalves Molluscs are soft-bodied animals inhabiting marine, land and Bivalves are molluscs made up of two shells joined by a hinge with freshwater habitats. The shells we commonly come across on the interlocking teeth. The shells are usually held together by a tough beach belong to one of two groups of molluscs, either gastropods ligament. These creatures also have a set of two tubes which which have one shell, or bivalves which have two shells. The material sometimes stick out from shell allowing the animal to breathe and making up the shell is secreted by special glands of the animal living feed. within it. Some commonly known bivalves include clams, cockles, mussels, scallops and oysters. Can you think of any others? Oysters and mussels attach themselves to solid objects such as jetty pylons or rocks on the sea floor and filter feed by taking Gastropod = One Shell Bivalve = Two Shells water into one tube and removing the tiny particles of plankton from the water. In contrast, scallops and cockles are moving Particular shell shapes have been adapted to suit the habitat and bivalves and can either swim through the conditions in which the animals live, helping them to survive. The water or pull themselves through the sand wedge shape of a cockle shell allows them to easily burrow into the with their muscular, soft bodies. sand. Ribs, folds and frills on many molluscs help to strengthen the shell and provide extra protection from predators. -

Tumbaga-Metal Figures from Panama: a Conservation Initiative to Save a Fragile Coll

SPRING 2006 IssuE A PUBLICATION OF THE PEABODY MUSEUM AND THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY, HARVARD UNIVERSITY • 11 DIVINITY AVENUE CAMBRIDGE, MA 02138 DIGGING HARVARD YARD No smoking, drinking, glass-break the course, which was ing-what? Far from being a puritani taught by William Fash, cal haven, early Harvard College was a Howells director of the colorful and lively place. The first Peabody Museum, and Harvard students did more than wor Patricia Capone and Diana ship and study: they smoked, drank, Loren, Peabody Museum and broke a lot of windows. None of associate curators. They which was allowed, except on rare were assisted by Molly occasion. In the early days, Native Fierer-Donaldson, graduate American and English youth also stud student in Archaeology, ied, side by side. Archaeological and and Christina Hodge, historical records of early Harvard Peabody Museum senior Students excavating outside Matthews Hall. Photo by Patricia bring to life the experiences of our curatorial assistant and Capor1e. predecessors, teaching us that not only graduate student in is there an untold story to be Archaeology at Boston unearthed, but also, that we may learn University. ALEXANDER MARSHACK new perspectives by reflecting on our Archaeological data recovered from ARCHIVE DONATED TO THE shared history: a history that reaches Harvard Yard enriches our view of the PEABODY MUSEUM beyond the university walls to local seventeenth- through nineteenth-cen Native American communities. tury lives of students and faculty Jiving The Peabody Museum has received the The Fall 2005 course Anthropology in Harvard Yard. In the seventeenth generous donation of the photographs 1130: The Archaeology of Harvard Yard century, Harvard Yard included among and papers of Alexander Marshack brought today's Harvard students liter its four buildings the Old College, the from his widow, Elaine. -

Guide to the Identification of Precious and Semi-Precious Corals in Commercial Trade

'l'llA FFIC YvALE ,.._,..---...- guide to the identification of precious and semi-precious corals in commercial trade Ernest W.T. Cooper, Susan J. Torntore, Angela S.M. Leung, Tanya Shadbolt and Carolyn Dawe September 2011 © 2011 World Wildlife Fund and TRAFFIC. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-0-9693730-3-2 Reproduction and distribution for resale by any means photographic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems of any parts of this book, illustrations or texts is prohibited without prior written consent from World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Reproduction for CITES enforcement or educational and other non-commercial purposes by CITES Authorities and the CITES Secretariat is authorized without prior written permission, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Any reproduction, in full or in part, of this publication must credit WWF and TRAFFIC North America. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC network, WWF, or the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The designation of geographical entities in this publication and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WWF, TRAFFIC, or IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership are held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint program of WWF and IUCN. Suggested citation: Cooper, E.W.T., Torntore, S.J., Leung, A.S.M, Shadbolt, T. and Dawe, C. -

ORNAMENT 30.3.2007 30.3 TOC 2.FIN 3/18/07 12:39 PM Page 2

30.3 COVERs 3/18/07 2:03 PM Page 1 992-994_30.3_ADS 3/18/07 1:16 PM Page 992 01-011_30.3_ADS 3/16/07 5:18 PM Page 1 JACQUES CARCANAGUES, INC. LEEKAN DESIGNS 21 Greene Street New York, NY 10013 BEADS AND ASIAN FOLKART Jewelry, Textiles, Clothing and Baskets Furniture, Religious and Domestic Artifacts from more than twenty countries. WHOLESALE Retail Gallery 11:30 AM-7:00 PM every day & RETAIL (212) 925-8110 (212) 925-8112 fax Wholesale Showroom by appointment only 93 MERCER STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10012 (212) 431-3116 (212) 274-8780 fax 212.226.7226 fax: 212.226.3419 [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] WHOLESALE CATALOG $5 & TAX I.D. Warehouse 1761 Walnut Street El Cerrito, CA 94530 Office 510.965.9956 Pema & Thupten Fax 510.965.9937 By appointment only Cell 510.812.4241 Call 510.812.4241 [email protected] www.tibetanbeads.com 1 ORNAMENT 30.3.2007 30.3 TOC 2.FIN 3/18/07 12:39 PM Page 2 volumecontents 30 no. 3 Ornament features 34 2007 smithsonian craft show by Carl Little 38 candiss cole. Reaching for the Exceptional by Leslie Clark 42 yazzie johnson and gail bird. Aesthetic Companions by Diana Pardue 48 Biba Schutz 48 biba schutz. Haunting Beauties by Robin Updike Candiss Cole 38 52 mariska karasz. Modern Threads by Ashley Callahan 56 tutankhamun’s beadwork by Jolanda Bos-Seldenthuis 60 carol sauvion’s craft in america by Carolyn L.E. Benesh 64 kristina logan. Master Class in Glass Beadmaking by Jill DeDominicis Cover: BUTTERFLY PINS by Yazzie Johnson and Gail Bir d, from top to bottom: Morenci tur quoise and tufa-cast eighteen karat gold, 7.0 centimeters wide, 2005; Morenci turquoise, lapis, azurite and fourteen karat gold, 5.1 centimeters wide, 1987; Morenci turquoise and tufa-cast eighteen karat gold, 5.7 centimeters wide, 2005; Tyrone turquoise, coral and tufa- cast eighteen karat gold, 7.6 centimeters wide, 2006; Laguna agates and silver, 7.6 centimeters wide, 1986.