'Love from Afar': Music and Longing Across Time, Space, and Diaspora

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title SCHOLARSHIP on ETHIOPIAN MUSIC

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository SCHOLARSHIP ON ETHIOPIAN MUSIC: PAST, PRESENT Title AND FUTURE PROSPECTS Author(s) SIMENEH, Betreyohannes African study monographs. Supplementary issue (2010), 41: Citation 19-34 Issue Date 2010-03 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/108286 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, Suppl.41: 19-34, March 2010 19 SCHOLARSHIP ON ETHIOPIAN MUSIC: PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE PROSPECTS SIMENEH Betreyohannes Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa University ABSTRACT Broad and signifi cant appraisals on Ethiopian studies have been carried out with thematic and disciplinary orientations from authors such as Bahru Zewde, Alula Pankhurest, Gebre Yntiso and Belete Bizuneh. One might expect music to be a relevant aspect of such works, yet it is hardly addressed, resulting in a dearth of independent and comprehensive assessments of Ethiopian music scholarship; a rare exception is the 3 volume Ethiopian Chris- tian Liturgical Chant: An Anthology edited by Kay Kaufman Shelemay and Peter Jeffery (1993–1997). Generally speaking, music is one of the most neglected themes in Ethiopian studies, especially as compared to the dominant subjects of history and linguistics. Although some progress in musical studies has recently developed, the existing scholarly literature remains confi ned to limited themes. Beside inadequate attention to various topics there are problems of misconceptions and lack of reciprocity in contemporary scholarship. This paper outlines the evolution of Ethiopian music scholarship and exposes general trends in the exist- ing body of knowledge by using critical works from a variety of disciplines. -

International Journal of Social Sciences and Management a Rapid Publishing Journal

International Journal of Social Sciences and Management A Rapid Publishing Journal ISSN 2091-2986 CrossRef, Google Scholar, International Society of Universal Research in Sciences (EyeSource), Journal TOCs, NewAvailable Jour, Scientific online Indexing at: Services, InfoBase Index, Open Academic Journals Index http://www.ijssm.org(OAJI), Scholarsteer, Jour Informatics, Directory of Research Journals Indexing (DRJI), International& Society for Research Activity http://www.nepjol.info/index.php/IJSSM/index (ISRA): Journal Impact Factor (JIF), Simon Fraser University Library, etc. Vol- 2(4), October 2015 Impact factor*: 3.389 *Impact factor is issued by SJIF INNO SPACE. Kindly note that this is not the IF of Journal Citation Report (JCR). For any type of query or feedback kindly contact at email ID: [email protected] R.N. Pati et al. (2015) Int. J. Soc. Sci. Manage. Vol-2, issue-4: 315-326 DOI: 10.3126/ijssm.v2i4.13620 Research Article CULTURAL RIGHTS OF TRADITIONAL MUSICIANS IN ETHIOPIA: THREATS AND CHALLENGES OF GLOBALISATION OF MUSIC CULTURE R.N. Pati1*, Shaik Yousuf. B1 and Abebaw Kiros2 1Department of Anthropology, Institute of Paleoenvironment and Heritage Conservation, Mekelle University, Mekelle, Ethiopia. 2Department of Music and Visual Arts, College of Social Sciences, AdiHaqi campus, Mekelle University, Mekelle, Ethiopia. Corresponding author’s email: [email protected] Abstract Ethiopia upholds unique cultural heritage and diverse music history in entire African continent. The traditional music heritage of Ethiopia has been globally recognized with its distinct music culture and symbolic manifestation. The traditional songs and music of the country revolves around core chord of their life and culture. The modern music of Ethiopia has been blended with combination of elements from traditional Ethiopian music and western music which has created a new trend in the music world. -

'Lovefromafar Publversion

'Love From Afar': Music and Longing Across Time, Space, and Diaspora The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Shelemay, Kay Kaufman. 2012. "'Love From Afar': Music and Longing Across Time, Space, and Diaspora." In Eranos Yearbook 70 (2009/2010-2011). Einsiedeln: Daimon Verlag. Presented as part of the Fetzer Institute Dialogues at Eranos - The Power of Love. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:16030682 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP ‘Love From Afar’: Music and Longing Across Time, Space, and Diaspora Kay Kaufman Shelemay Among the most powerful and enduring of the many emotions in human life is love. And surely no other emotion is so pervasively expressed through musical composition and performance. Neuroscientists have recently argued for music’s role in the evolution of the human species as well as the on-going role of music in shaping human social life. The power of music to index emotional states, including feelings of attachment and love, is at the center of Steven Mithen’s suggestion that Neanderthals communicated through a sonic proto-language that was a precursor to Both human music and language. (Mithen, p 26-27, 94, 221) Daniel Levitin has included love songs in his “soundtrack of civilization,” a typology that seeks to take “account of the impact music has had on the course of our social history” (Levitin, p. -

Kirar, Masinko, Begena, Kebero and Washint

International Journal of Scientific Research and Management (IJSRM) ||Volume||08||Issue||01||Pages||SH-2020-591-596||2020|| Website: www.ijsrm.in ISSN (e): 2321-3418 DOI: 10.18535/ijsrm/v8i01.sh02 The analysis of Ethiopian traditional music instrument through indigenous knowledge (kirar, masinko, begena, kebero and washint/flute) Girmaw Ashebir Sinshaw (M.Ed.) Masters Art Education in Theater) and Lecturer, Ethiopian Language(s) and Literature-Amharic, Director for Public relation and communications directorate, Debremarkos University , Gojjam, Amhara, Ethiopia Abstract: This article aims to explore and analytics about Ethiopian traditional music instrument through indigenous knowledge (kirar, masinko, Begena, kebero and washint/flute). The researcher would have observation and referring the difference documentations. Kirar, and masinko are mostly have purposeful for local music including washint, the others which is Kebero, Begena have use full in the majority time for church purpose. Ethiopia has extended culture, art and indigenous knowledge related to original own music. Their studies have qualitative research design that has descriptive methodology to more exploring the traditional music’s free statement descriptions. Its researcher mainly has providing the descriptive information about the Ethiopian traditional music instrument as analytical finding out. Kay words; Kirar, Masinqo, Kebero, Washint, Begena, Traditional, Music, Instrument 1. Introduction Folk music includes both traditional music and the genre that evolved from it during the 20th century folk revival. The term originated in the 19th century but is often applied to music that is older than that. Some types of folk music are also called world music. "Traditional folk music" has been defined in several ways: as music transmitted orally, music with unknown composers, or music performed by custom over a long period of time. -

Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music

A clarinet (soprano) albogue tubes in a frame. USE clarinet BT double reed instrument UF kechruk a-jaeng alghōzā BT xylophone USE ajaeng USE algōjā anklung (rattle) accordeon alg̲hozah USE angklung (rattle) USE accordion USE algōjā antara accordion algōjā USE panpipes UF accordeon A pair of end-blown flutes played simultaneously, anzad garmon widespread in the Indian subcontinent. USE imzad piano accordion UF alghōzā anzhad BT free reed instrument alg̲hozah USE imzad NT button-key accordion algōzā Appalachian dulcimer lõõtspill bīnõn UF American dulcimer accordion band do nally Appalachian mountain dulcimer An ensemble consisting of two or more accordions, jorhi dulcimer, American with or without percussion and other instruments. jorī dulcimer, Appalachian UF accordion orchestra ngoze dulcimer, Kentucky BT instrumental ensemble pāvā dulcimer, lap accordion orchestra pāwā dulcimer, mountain USE accordion band satāra dulcimer, plucked acoustic bass guitar BT duct flute Kentucky dulcimer UF bass guitar, acoustic algōzā mountain dulcimer folk bass guitar USE algōjā lap dulcimer BT guitar Almglocke plucked dulcimer acoustic guitar USE cowbell BT plucked string instrument USE guitar alpenhorn zither acoustic guitar, electric USE alphorn Appalachian mountain dulcimer USE electric guitar alphorn USE Appalachian dulcimer actor UF alpenhorn arame, viola da An actor in a non-singing role who is explicitly alpine horn USE viola d'arame required for the performance of a musical BT natural horn composition that is not in a traditionally dramatic arará form. alpine horn A drum constructed by the Arará people of Cuba. BT performer USE alphorn BT drum adufo alto (singer) arched-top guitar USE tambourine USE alto voice USE guitar aenas alto clarinet archicembalo An alto member of the clarinet family that is USE arcicembalo USE launeddas associated with Western art music and is normally aeolian harp pitched in E♭. -

Title SCHOLARSHIP on ETHIOPIAN MUSIC: PAST, PRESENT AND

SCHOLARSHIP ON ETHIOPIAN MUSIC: PAST, PRESENT Title AND FUTURE PROSPECTS Author(s) SIMENEH, Betreyohannes African study monographs. Supplementary issue (2010), 41: Citation 19-34 Issue Date 2010-03 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/108286 Right Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, Suppl.41: 19-34, March 2010 19 SCHOLARSHIP ON ETHIOPIAN MUSIC: PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE PROSPECTS SIMENEH Betreyohannes Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa University ABSTRACT Broad and signifi cant appraisals on Ethiopian studies have been carried out with thematic and disciplinary orientations from authors such as Bahru Zewde, Alula Pankhurest, Gebre Yntiso and Belete Bizuneh. One might expect music to be a relevant aspect of such works, yet it is hardly addressed, resulting in a dearth of independent and comprehensive assessments of Ethiopian music scholarship; a rare exception is the 3 volume Ethiopian Chris- tian Liturgical Chant: An Anthology edited by Kay Kaufman Shelemay and Peter Jeffery (1993–1997). Generally speaking, music is one of the most neglected themes in Ethiopian studies, especially as compared to the dominant subjects of history and linguistics. Although some progress in musical studies has recently developed, the existing scholarly literature remains confi ned to limited themes. Beside inadequate attention to various topics there are problems of misconceptions and lack of reciprocity in contemporary scholarship. This paper outlines the evolution of Ethiopian music scholarship and exposes general trends in the exist- ing body of knowledge by using critical works from a variety of disciplines. It also introduces the major subjects and personalities involved in Ethiopian musical studies. The paper concludes with highlights of pertinent problematic issues followed by practical suggestions for fostering Ethiopian music scholarship. -

Music and Dance of Wolaita and Ethiopia Unit Grades 7 – 12

Music and Dance of Wolaita and Ethiopia Unit Grades 7 – 12 Unit Title Folklore: Wolaita Dance and Music Fulbright Ethiopia, Indigenous Wisdom & Culture Teachers Gerald Savage – Pittsburgh CAPA 6-12, and Irene Chepngetich – Pittsburgh Brashear PITTSBURGH PUBLIC SCHOOL DISTRICT Subject and Music and Dance – Grades 7 to 12 grade levels Time Frame and 32 days/ One Unit divided in 3 cluster lessons duration 1-2 class periods (44 minutes each) CCSS (Common Core Standards): Grades 7 – 12 • Students compare in two or more arts how the characteristic materials of each art (that is, sound in music, visual stimuli in visual arts, movement in dance, human interrelationships in theatre) can be used to transform similar events, scenes, emotions, or ideas into works of art • Students describe ways in which the principles and subject matter of other disciplines taught in the school are interrelated with those of music (e.g., language arts: issues to be considered in setting texts to music; mathematics: frequency ratios of intervals; sciences: the human hearing process and hazards to hearing; social studies: historical and social events and movements chronicled in or influenced by musical works) DOMAIN: Music and Dance CLUSTER: • Ethiopian History • Ethiopian various songs and dance • Walaita Cultural Music and Dance STANDARD: PA Arts Standard—9.2 Academic Standards for the Arts and Humanities 9.2. Historical and Cultural Contexts 9.2.3. GRADE 3 9.2.5. GRADE 5 9.2.8. GRADE 8 9.2.12. GRADE 12 A. Explain the historical, cultural and social context of an individual work in the arts. B. -

The Universal Lyre: Three Perspectives

The Universal Lyre: Three Perspectives by Diana Rowan EOPLE are often entranced by the harp for for krar and begena. Besides his many recordings, its mystical sound and image, hearkening Temesgen has instructional DVDs for krar and back to the most ancient of times. Whether begena, with additional titles in the works. He is we realize it or not, the harp’s roots lie deep within also a source for people looking to purchase these ourP collective consciousness worldwide. The instruments. instrument touches us in dual fashion, both in Michalis Georgiou of Cyprus (http://terpandros. body and soul. The harp or lyre may be found in com/) is steeped in that island’s ancient, always very similar form across the Middle East, Greece visible history, and over twenty years ago moved into and Africa. Everywhere they have been found, the the world of instrument reconstruction. Already a instruments have been used to address the sacred lifelong musician, Georgiou took to his workshop and the secular throughout the ages. Note that to recreate ancient Greek instruments. H has built “harp” and “lyre” will be used interchangeably here more than twenty-three different types of stringed as many construction and playing techniques are instruments, many of which can be classified as lyres. similar as is the use of the instrument. He has also formed a large award-winning student- based orchestra to perform reconstructions of Three Artist-Scholars ancient music on these instruments, leading to: …the creation of Terpandros, named after the great Three contemporary artists are involved in the field musician of antiquity. -

Garritan World Instruments

A User’s Guide to GARRITAN WORLD INSTRUMENTS Including the ARIA™ Player This guide written by Gary Garritan Produced by: Gary Garritan Programming: Chad Beckwith, Markleford Friedman ARIA Engine Development: Plogue Art et Technologie, Inc. Additional Programming: Eric Patenaude, Tom Hopkins Document Editing: Jim Williams MIDI/SFZ Programming: Chad Beckwith, Markleford Friedman Art Direction: James Mireau Project Management: Max Deland Software Development: Jeff Hurchalla Manual Layout: Adina Cucicov Additional Samples: Herman Witkam, Doru Malaia, Jack De Mello, Gene Nery, McGill University Garritan World Instruments™ is a trademark of Garritan Corp. Use of the Garritan World Instruments library and the contents herein are subject to the terms and conditions of the license agreement distributed with the library. You should carefully read the license agreement before using this product. The sounds presented in Garritan World Instruments are protected by copyright and may not be distributed, whether modified or unmodified. The Guide to Garritan World Instruments and instrument lists contained herein are also covered by copyright. ARIA™ is a trademark of Garritan and Plogue Art et Technologie, Inc. FINALE is a trademark of MakeMusic, Sibelius is a trademark of Avid Technolgies, Inc., Endless Wave is a trademark of Conexant, Inc., and any other trademarks of third-party programs are trademarks of their respective owners. No part of this publication may be copied, repro- duced, or otherwise transmitted or recorded, for any purpose, without prior written permission from Garritan Corp. The information contained herein may change without notice and does not represent a commitment on the part of Garritan Corporation. Garritan World Instruments Garritan Corporation P.O. -

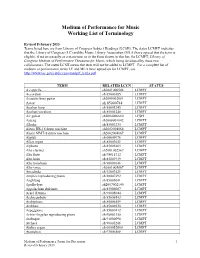

Medium of Performance for Music: Working List of Terminology

Medium of Performance for Music Working List of Terminology Revised February 2013 Terms listed here are from Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH). The status LCMPT indicates that the Library of Congress (LC) and the Music Library Association (MLA) have agreed that the term is eligible, if not necessarily as a main term or in the form shown in this list, for LCMPT, Library of Congress Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music, which being developed by these two collaborators. The status LCSH means the term will not be added to LCMPT. For a complete list of medium of performance terms LC and MLA have agreed on for LCMPT, see http://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/medprf_lcmla.pdf. -

Addis Ababa University College of Performing and Visual Arts Yared School of Music

Addis Ababa University College of Performing and Visual Arts Yared School of Music Analysis of Ethiopian ‘Kignts’ used dominantly in popular songs produced as commercial music in the 1960-1980s: The Modern recording songs in Addis Ababa. By Hilina Fekadu December, 2020 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 1 Addis Ababa University Yared School of Music Analysis of Ethiopian ‘Kignts’ used dominantly in popular songs produced as commercial music in the 1960-1980s: The Modern recording songs in Addis Ababa. By Hilina Fekadu A thesis Submitted to the Department of Yared School of Music in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Art in Music Advisor: Ezra Abate (PhD) December, 2020 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 2 Addis Ababa University College of Performing and Visual Arts Yared School of Music Analysis of Ethiopian ‘Kignts’ used dominantly in popular songs produced as commercial music in the 1960-1980s: The Modern recording songs in Addis Ababa. By Hilina Fekadu Approved by Board of examiners Advisor ____________________________ Signature___________________ External Examiner ____________________Signature__________________ Internal Examiner ______________________Signature__________________ Director of Yared School of Music _________Signature __________________ 3 Acknowledgments I am indebted to Dr. Ezra Abate who has given me considerable support as advisor of my research work. His valuable advice and logical comments helped me a great to shape the paper in its present form without whom this paper would not have been completed. I also would like to thank the musician who deserves gratitude for their willingness to be interviewed. Following, I would like to thank my most caring husband Addis G/Hiwot, and my family for their priceless help encouragement. -

Draft Authorized Vocabulary for Medium of Performance Statements

MEDIUM OF PERFORMANCE TERMS FOR LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MEDIUM OF PERFORMANCE THESAURUS FOR MUSIC DRAFT AUTHORIZED VOCABULARY FOR MEDIUM OF PERFORMANCE STATEMENTS IN BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORDS AS AGREED ON BY THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS AND THE MUSIC LIBRARY ASSOCIATION February 2013 Introduction The Library of Congress, in cooperation with the Music Library Association, is developing a new thesaurus of terms representing vocabulary for the medium of performance of musical works, Library of Congress Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music (LCMPT). The vocabulary is intended to be used, at least initially, for two bibliographic purposes: 1) to retrieve music by its medium of performance in library catalogs, as is now done by the controlled vocabulary, Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH); 2) to record the element “medium of performance” of musical works according to the cataloging standard, RDA: Resource Description and Access (RDA). The table that follows, which contains approximately 850 terms, updates the previously posted table of terms the collaborators recommend for the new medium of performance thesaurus. The table is a working document, subject to change. Background Medium of performance is now recognized as a separate and distinct bibliographic facet that should have its own vocabulary and vocabulary structure. Searches by medium should enable users to retrieve music by a particular instrument or instrumental group, voice or vocal group, or other medium of performance term or terms the searcher may specify. As presently incorporated into LCSH, medium of performance terms may occur in headings in two ways: either along with a term for genre, form, type, or style of music (as in Sonatas (Violin and piano)), or in headings that have only one or more medium terms in them (as in Violin and piano music).