Unit 13 Noakhali

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

01720Joya Chatterji the Spoil

This page intentionally left blank The Spoils of Partition The partition of India in 1947 was a seminal event of the twentieth century. Much has been written about the Punjab and the creation of West Pakistan; by contrast, little is known about the partition of Bengal. This remarkable book by an acknowledged expert on the subject assesses partition’s huge social, economic and political consequences. Using previously unexplored sources, the book shows how and why the borders were redrawn, as well as how the creation of new nation states led to unprecedented upheavals, massive shifts in population and wholly unexpected transformations of the political landscape in both Bengal and India. The book also reveals how the spoils of partition, which the Congress in Bengal had expected from the new boundaries, were squan- dered over the twenty years which followed. This is an original and challenging work with findings that change our understanding of parti- tion and its consequences for the history of the sub-continent. JOYA CHATTERJI, until recently Reader in International History at the London School of Economics, is Lecturer in the History of Modern South Asia at Cambridge, Fellow of Trinity College, and Visiting Fellow at the LSE. She is the author of Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition (1994). Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society 15 Editorial board C. A. BAYLY Vere Harmsworth Professor of Imperial and Naval History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow of St Catharine’s College RAJNARAYAN CHANDAVARKAR Late Director of the Centre of South Asian Studies, Reader in the History and Politics of South Asia, and Fellow of Trinity College GORDON JOHNSON President of Wolfson College, and Director, Centre of South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society publishes monographs on the history and anthropology of modern India. -

The Great Calcutta Killings Noakhali Genocide

1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE 1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE A HISTORICAL STUDY DINESH CHANDRA SINHA : ASHOK DASGUPTA No part of this publication can be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the author and the publisher. Published by Sri Himansu Maity 3B, Dinabandhu Lane Kolkata-700006 Edition First, 2011 Price ` 500.00 (Rupees Five Hundred Only) US $25 (US Dollars Twenty Five Only) © Reserved Printed at Mahamaya Press & Binding, Kolkata Available at Tuhina Prakashani 12/C, Bankim Chatterjee Street Kolkata-700073 Dedication In memory of those insatiate souls who had fallen victims to the swords and bullets of the protagonist of partition and Pakistan; and also those who had to undergo unparalleled brutality and humility and then forcibly uprooted from ancestral hearth and home. PREFACE What prompted us in writing this Book. As the saying goes, truth is the first casualty of war; so is true history, the first casualty of India’s struggle for independence. We, the Hindus of Bengal happen to be one of the worst victims of Islamic intolerance in the world. Bengal, which had been under Islamic attack for centuries, beginning with the invasion of the Turkish marauder Bakhtiyar Khilji eight hundred years back. We had a respite from Islamic rule for about two hundred years after the English East India Company defeated the Muslim ruler of Bengal. Siraj-ud-daulah in 1757. But gradually, Bengal had been turned into a Muslim majority province. -

MYTH OR REALITY ABOUT the HINDU-WOMEN CONVERSION to ISLAMIC BELIEF DURING the NOAKHALI RIOTS Md

THE PARTITION OF INDIA 1947: MYTH OR REALITY ABOUT THE HINDU-WOMEN CONVERSION TO ISLAMIC BELIEF DURING THE NOAKHALI RIOTS Md. Pervejur Rahaman1, Dr. Mark Doyle1, Dr. Andrew Polk1 , Dr. Martha Norkunas1 1. Department of History, Middle Tennessee State university, Murfreesboro, Tennessee, USA Introduction Literature Review Methodology The partition of India in 1947 caused one of the Historians have often failed to portray the Hindu- Gandhi Preached in Noakhali to Bridge great migrations in human history. In 1947, in the Muslim relations in Bangladesh, which then 1. Interviews, archival study, historical photos, the Gap between Hindus and Muslims blink of an eye, the British colonial power became Bengal. The good relation between the ethical procedures; partitioned India on the basis of Hindu and Hindu-Muslim community has constantly been Muslim majority. Pakistan was pieced together overlooked by the historians’ narrative. There 2 Written memories and letters; combining two far-apart wings of India: East were stories that would not manifest the fear of 3. Gandhi sojourned to Noakhali: November 6, Pakistan and West Pakistan. Within a short space ‘other’ religion in the Noakhali-Tippera areas. 1946: (many people accepted and acted as of a few months, around twelve million people Thus, the partition historians use context-free Gandhi; he just got the most attention. Kindness moved to newly created Pakistan and India. The lens when they talk about Hindu and Muslim was always a primary part of the narrative. wave of the partition forced people -

Index More Information

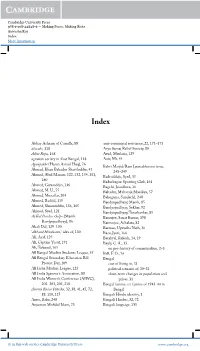

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42828-6 — Making Peace, Making Riots Anwesha Roy Index More Information Index 271 Index Abhay Ashram of Comilla, 88 anti-communal resistance, 22, 171–175 abwabs, 118 Arya Samaj Relief Society, 80 Adim Ripu, 168 Azad, Maulana, 129 agrarian society in East Bengal, 118 Aziz, Mr, 44 Agunpakhi (Hasan Azizul Huq), 76 Babri Masjid/Ram Janmabhoomi issue, Ahmad, Khan Bahadur Sharifuddin, 41 248–249 Ahmed, Abul Mansur, 122, 132, 134, 151, Badrudduja, Syed, 35 160 Badurbagan Sporting Club, 161 Ahmed, Giyasuddin, 136 Bagchi, Jasodhara, 16 Ahmed, M. U., 75 Bahadur, Maharaja Manikya, 57 Ahmed, Muzaffar, 204 Bahuguna, Sunderlal, 240 Ahmed, Rashid, 119 Bandyopadhyay, Manik, 85 Ahmed, Shamsuddin, 136, 165 Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar, 92 Ahmed, Syed, 121 Bandyopadhyay, Tarashankar, 85 Aj Kal Porshur Golpo (Manik Banerjee, Sanat Kumar, 198 Bandyopadhyay), 86 Bannerjee, Ashalata, 82 Akali Dal, 129–130 Barman, Upendra Nath, 36 ‘Akhand Hindustan,’ idea of, 130 Basu, Jyoti, 166 Ali, Asaf, 129 Batabyal, Rakesh, 14, 19 Ali, Captain Yusuf, 191 Bayly, C. A., 13 Ali, Tafazzal, 165 on pre-history of communalism, 2–3 All Bengal Muslim Students League, 55 Bell, F. O., 76 All Bengal Secondary Education Bill Bengal Protest Day, 109 cost of living in, 31 All India Muslim League, 123 political scenario of, 30–31 All India Spinner’s Association, 88 short-term changes in population and All India Women’s Conference (AIWC), prices, 31 202–203, 205, 218 Bengal famine. see famine of 1943-44 in Amrita Bazar Patrika, 32, 38, 41, 45, 72, Bengal 88, 110, 115 Bengali Hindu identity, 1 Amte, Baba, 240 Bengali Hindus, 32, 72 Anjuman Mofidul Islam, 73 Bengali language, 135 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42828-6 — Making Peace, Making Riots Anwesha Roy Index More Information 272 Index The Bengali Merchants Association, 56 C. -

Honourably Dead: Permissable Violence Against Women

Honourably Dead Permissible Violence Against Women There were other attacks, but God was kind, he saved us each time. There was a notorious gang in a neighbouring village who went and, looted people, attacked them. We were afraid they would come for us. We put sandbags on the roof of our house, some people In the villages of Head Junu, Hindus threw their young daughters put stones. We also had guns and sticks. ... Our work was such into wells, dug trenches and buried them alive. Some were burnt to that our men had to go out at odd times, so they always had guns death, some were made to touch electric wires to prevent the Mus with them. The leader of that gang tried to attack us three times but lims from touching them. We heard of such happenings all the time something or the other stopped them. Once, the river swelled so they after August 16. We heard all this. couldn't cross over, another time he was on his way to our village when he got the news that the roof of his house had collapsed. He had The Muslims used to announce that they would take away our to turn back. So we escaped, God was kind to us ... daughters. They would force their way into homes and pick up young girls and women. Ten or twenty of them would enter, tie up the Gyan Deyi menfolk and take the women. We saw many who had been raped and disfigured, their faces and breasts scarred, and then abandoned. -

2Hist-Course-Outcome

Bankim Sardar College A College with Potential For Excellence Department of History Programme Specific Outcome(PSO) A Hons. Graduate of History should possess the capability to: - Possess extensive reading skills. Be aware of the world history, and India’s standpoint since ancient times. Knowledgeable about the age old traditions, culture, ethics and ethnic character. Aware of how different social races have come up for the quest of power, struggle, victory and loss over throne and thus, the changing economy. Strengthen values, virtues and principles by learning and realizing the lessons from history. Developing writing skills without favouring bias to any rules or empire or period. Transforming into a knowledgeable man / woman with strong views and arguments having strong understanding and grip of history. There are several interesting and alluring career options a History Hons Graduate can pursue, i.e, I. Archaeologist II. Museologist III. Museum Curator IV. Archivist V. Historian VI. Teacher VII. Civil servant etc. Course Outcome_for UG Courses_Department of History Bankim Sardar College Course Outcome Semester Paper Core Course Course Outcome Outcome (CO) I. ReconstructingAncient IndianHistory: a) Early Indian notions ofHistory b) Sourcesand tools of historicalreconstruction. Story of Man :a systematic study of the c) Historicalinterpretations(withspecialrefe rence to gender,environment, past-includes polity, society, education, technologyandregions) economy, custom, religion- culture II. Hunter-gatherers and the advent offood from earliest time to present day. products Periodisation of history a) Paleolithiccultures-sequence Source materials of ancient Indian anddistribution;stone history: Archaeological and Literary industriesandothertechnologicaldevelopments. sources. CO 01. b) Mesolithiccultures– Prehistory and Proto-historic period of History of regionalandchronologicaldistribution;newdevelop ancient India. -

Calcutta & West Bengal, 1950S

People, Politics and Protests I Calcutta & West Bengal, 1950s – 1960s Sucharita Sengupta & Paula Banerjee Anwesha Sengupta 2016 1. Refugee Movement: Another Aspect of Popular Movements in West Bengal in the 1950s and 1960s Sucharita Sengupta & Paula Banerjee 1 2. Tram Movement and Teachers’ Movement in Calcutta: 1953-1954 Anwesha Sengupta 25 Refugee Movement: Another Aspect of Popular Movements in West Bengal in the 1950s and 1960s ∗ Sucharita Sengupta & Paula Banerjee Introduction By now it is common knowledge how Indian independence was born out of partition that displaced 15 million people. In West Bengal alone 30 lakh refugees entered until 1960. In the 1970s the number of people entering from the east was closer to a few million. Lived experiences of partition refugees came to us in bits and pieces. In the last sixteen years however there is a burgeoning literature on the partition refugees in West Bengal. The literature on refugees followed a familiar terrain and set some patterns that might be interesting to explore. We will endeavour to explain through broad sketches how the narratives evolved. To begin with we were given the literature of victimhood in which the refugees were portrayed only as victims. It cannot be denied that in large parts these refugees were victims but by fixing their identities as victims these authors lost much of the richness of refugee experience because even as victims the refugee identity was never fixed as these refugees, even in the worst of times, constantly tried to negotiate with powers that be and strengthen their own agency. But by fixing their identities as victims and not problematising that victimhood the refugees were for a long time displaced from the centre stage of their own experiences and made “marginal” to their narratives. -

Colonial Cousins: Communalism and Nationalism in Modern India

Rakesh Batabyal. Communalism in Bengal: From Famine to Noakhali, 1943-1947. London: Thousand Oaks, 2005. 428 pp. $97.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-7619-3335-9. Reviewed by Anirudh Deshpande Published on H-Asia (July, 2007) For readers unfamiliar with the terms in such as the one witnessed in Gujarat in 2002, are which modern Indian history is usually written, integral to communalism in India. Readers who communalism should be described before the re‐ have not read much of Indian history but are well view of the book is presented. The word commu‐ versed in European and American history can nalism obviously comes from community and easily understand "Indian communalism" with communal which may mean entirely different reference to similar developments in the context things to people in the West. The closest parallels of many European and American countries. Al‐ of communalism in India are racism and anti- though there is another form in which communal‐ Semitism, etc. in the West; while in India commu‐ ism manifests itself in India, called "casteism," nalism makes a person prefer a certain communal communalism in general refers to religious com‐ identity over other secular identities. In many munalism. India, like most other countries, has a parts of the West a position of racial superiority is history of religious conflict going back to the an‐ assumed by many individuals and social groups cient period, but communalism refers to a mod‐ over people of non-European extraction. In both ern consolidation of religious groups and identi‐ instances religious or race identities are internal‐ ties and the politicization of religious organiza‐ ized and displayed by individuals who believe in tion and conflict which began during the colonial myths, which constitute an ideology. -

Noakhali Riots: This Day in History – Oct 10

Noakhali Riots: This Day in History – Oct 10 On 10 October 1946, riots engulfed the Noakhali and Tipperah Districts of Bengal (in present-day Bangladesh) where the Hindu community was targeted. This is an important event in the modern history of the subcontinent, which ultimately led to partition of India. Hence, it is important to know about this tragic event for the IAS exam.In 1946, the times were tense in many parts of the subcontinent. The British had promised to grant independence to its prized colony but there was no concrete decision on how to go about the transfer of power. ● The Muslim League was demanding a separate Muslim state of Pakistan. This was not agreed upon by the Indian National Congress. Areas, where there was not a clear majority for one of the two communities, were reeling in tension as to what would happen; whether the country would be partitioned and if that took place, which side of the border would they lie. This tension was causing sporadic riots in places. ● The Muslim League called for Direct Action and August 16, 1946 was announced as the ‘Direct Action Day’ to show their strength. The League leaders called for ‘action’ in order to get their demand for Pakistan fulfilled. ● Many provocative speeches were made and this resulted in one of the worst communal riots in history – the Great Calcutta Killings. Events of the Riots [caption id="attachment_41978" align="alignright" width="300"] Mahatma Gandhi in Noakhali, 1946[/caption] ● In Noakhali, which was not much affected during the Calcutta killings, the violence started on 10 October. -

East Bengali Refugee Narratives of Communal Violence

Interrogating Victimhood: East Bengali Refugee Narratives of Communal Violence Nilanjana Chatterjee Department of Anthropology University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill Introduction In this paper I am interested in analyzing the self-representation of Hindu East Bengali refugees as victims of Partition violence so as to historicize and politicize their claims to inclusion within India and their entitlement to humanitarian assistance in the face of state and public disavowal. I focus on the main components of their narratives of victimhood, which tend to be framed in an essentializing rhetoric of Hindu-Muslim difference and involve the demonization of “the Muslim.” I conclude with a brief consideration of the implications of this structure of prejudice for relations between the two communities in West Bengal and the rise of Hindu fundamentalism nationwide. A story I was told while researching East Bengali refugee agency and self-settlement strategies in West Bengal bring these issues together for me in a very useful way. Dr. Shantimoy Ray, professor of history and East Bengali refugee activist had been sketching the history of the refugee squatter colony Santoshpur, referred to the enduring sense of betrayal, loss and anger felt by East Bengalis after the partition of Bengal in 1947: becoming strangers in their own land which constituted part of the Muslim nation of Pakistan, being forced to leave and rebuild their lives in West Bengal in India, a “nation” that was nominally theirs but where they were faced with dwindling public sympathy and institutional apathy. Spurred by their bastuhara (homeless) condition-- a term which gained political significance and which referred to their Partition victimhood, groups of middle and working class refugees began to “grab” land and resettle themselves in West Bengal. -

Refugee?: Bengal Partition in Literature and Cinema

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-24-2015 12:00 AM "More or Less" Refugee?: Bengal Partition in Literature and Cinema Sarbani Banerjee The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Prof. Nandi Bhatia The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Sarbani Banerjee 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Sarbani, ""More or Less" Refugee?: Bengal Partition in Literature and Cinema" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3125. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3125 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i “MORE OR LESS” REFUGEE? : BENGAL PARTITION IN LITERATURE AND CINEMA (Thesis format: Monograph) by Sarbani Banerjee Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Sarbani Banerjee 2015 ii ABSTRACT In this thesis, I problematize the dominance of East Bengali bhadralok immigrant’s memory in the context of literary-cultural discourses on the Partition of Bengal (1947). -

The Collapse of Khaksar Organization: a Historical Review of the Dispelling of a Potential Movement in Bengal

https://doi.org/10.37948/ensemble-2020-0201-a015 THE COLLAPSE OF KHAKSAR ORGANIZATION: A HISTORICAL REVIEW OF THE DISPELLING OF A POTENTIAL MOVEMENT IN BENGAL Saumya Bose *¹ † Article Ref. No.: Abstract: 20020565N1MLSE The development of Muslim politics in Bengal was somewhat different from the upper Indian Muslim politics because of the strongly agrarian connection of the Bengali Muslim masses. The zamindars and moneylenders happened to be Hindu. As a result Article History: of the first half of the twentieth century, the peasant revolt Submitted on 05 Feb 2020 against the zamindars for the protection of their tenurial rights Accepted on 06 May 2020 took somewhat communal character. In the urban area, the Published online on 08 May 2020 Muslim educated middle classes were latecomers in the job sectors, and naturally, they have to face stiff competition to find their foothold. In this situation, by the 1930s it became open for any Muslim party to mobilize the Muslim masses in their favour providing that it would safeguard their interests. In light of this Keywords: changes, this present study will try to find out what were the Divide and Rule Policy, Simla Deputation, Morley Minto Reform ideology and programmes of the Khaksar movement and why Act, Bengal Pact, Pakistan did it fail to capitulate the existing situation in Bengal and make Movement a stronghold in Bengal. I Introduction In pre-independent Bengal, Muslims were the majority community. But economically, they were backward. Even before the 1920s, they were politically backward, too, in comparison with the Hindus. The non-cooperation-Khilafat movement of 1920 brought the Muslim masses into organized politics.