Tuberculosis: 4. Pulmonary Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identifying COPD by Crackle Characteristics

BMJ Open Resp Res: first published as 10.1136/bmjresp-2020-000852 on 5 March 2021. Downloaded from Respiratory epidemiology Inspiratory crackles—early and late— revisited: identifying COPD by crackle characteristics Hasse Melbye ,1 Juan Carlos Aviles Solis,1 Cristina Jácome,2 Hans Pasterkamp3 To cite: Melbye H, Aviles ABSTRACT Key messages Solis JC, Jácome C, et al. Background The significance of pulmonary crackles, Inspiratory crackles— by their timing during inspiration, was described by Nath early and late—revisited: and Capel in 1974, with early crackles associated with What is the key question? identifying COPD by bronchial obstruction and late crackles with restrictive ► In the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary crackle characteristics. defects. Crackles are also described as ‘fine’ or disease (COPD), is it more useful to focus on the tim- BMJ Open Resp Res ‘coarse’. We aimed to evaluate the usefulness of crackle ing of crackles than on the crackle type? 2021;8:e000852. doi:10.1136/ bmjresp-2020-000852 characteristics in the diagnosis of chronic obstructive What is the bottom line? pulmonary disease (COPD). ► Pulmonary crackles are divided into two types, ‘fine’ Methods In a population-based study, lung sounds Received 2 December 2020 and ‘coarse’ and coarse inspiratory crackles are re- Revised 2 February 2021 were recorded at six auscultation sites and classified in garded to be typical of COPD. In bronchial obstruc- Accepted 5 February 2021 participants aged 40 years or older. Inspiratory crackles tion crackles tend to appear early in inspiration, and were classified as ‘early’ or ‘late and into the types’ this characteristic of the crackle might be easier for ‘coarse’ and ‘fine’ by two observers. -

Age-Related Pulmonary Crackles (Rales) in Asymptomatic Cardiovascular Patients

Age-Related Pulmonary Crackles (Rales) in Asymptomatic Cardiovascular Patients 1 Hajime Kataoka, MD ABSTRACT 2 Osamu Matsuno, MD PURPOSE The presence of age-related pulmonary crackles (rales) might interfere 1Division of Internal Medicine, with a physician’s clinical management of patients with suspected heart failure. Nishida Hospital, Oita, Japan We examined the characteristics of pulmonary crackles among patients with stage A cardiovascular disease (American College of Cardiology/American Heart 2Division of Respiratory Disease, Oita University Hospital, Oita, Japan Association heart failure staging criteria), stratifi ed by decade, because little is known about these issues in such patients at high risk for congestive heart failure who have no structural heart disease or acute heart failure symptoms. METHODS After exclusion of comorbid pulmonary and other critical diseases, 274 participants, in whom the heart was structurally (based on Doppler echocar- diography) and functionally (B-type natriuretic peptide <80 pg/mL) normal and the lung (X-ray evaluation) was normal, were eligible for the analysis. RESULTS There was a signifi cant difference in the prevalence of crackles among patients in the low (45-64 years; n = 97; 11%; 95% CI, 5%-18%), medium (65-79 years; n = 121; 34%; 95% CI, 27%-40%), and high (80-95 years; n = 56; 70%; 95% CI, 58%-82%) age-groups (P <.001). The risk for audible crackles increased approximately threefold every 10 years after 45 years of age. During a mean fol- low-up of 11 ± 2.3 months (n = 255), the short-term (≤3 months) reproducibility of crackles was 87%. The occurrence of cardiopulmonary disease during follow-up included cardiovascular disease in 5 patients and pulmonary disease in 6. -

Assessing and Managing Lung Disease and Sleep Disordered Breathing in Children with Cerebral Palsy Paediatric Respiratory Review

Paediatric Respiratory Reviews 10 (2009) 18–24 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Paediatric Respiratory Reviews CME Article Assessing and managing lung disease and sleep disordered breathing in children with cerebral palsy Dominic A. Fitzgerald 1,3,*, Jennifer Follett 2, Peter P. Van Asperen 1,3 1 Department of Respiratory Medicine, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia 2 Department of Physiotherapy, The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia 3 The Children’s Hospital at Westmead Clinical School, Discipline of Paediatrics & Child Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia EDUCATIONAL AIMS To appreciate the insidious evolution of suppurative lung disease in children with cerebral palsy (CP). To be familiar with the management of excessive oral secretions in children with CP. To understand the range of sleep problems that are more commonly seen in children with CP. To gain an understanding of the use of non-invasive respiratory support for the management of airway clearance and sleep disordered breathing in children with CP. ARTICLE INFO SUMMARY Keywords: The major morbidity and mortality associated with cerebral palsy (CP) relates to respiratory compromise. Cerebral palsy This manifests through repeated pulmonary aspiration, airway colonization with pathogenic bacteria, Pulmonary aspiration the evolution of bronchiectasis and sleep disordered breathing. An accurate assessment involving a Suppurative lung disease multidisciplinary approach and relatively simple interventions for these conditions can lead to Physiotherapy significant improvements in the quality of life of children with CP as well as their parents and carers. This Airway clearance techniques Obstructive sleep apnoea review highlights the more common problems and potential therapies with regard to suppurative lung Sleep disordered breathing disease and sleep disordered breathing in children with CP. -

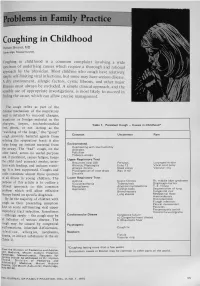

Problems in Family Practice

problems in Family Practice Coughing in Childhood Hyman Sh ran d , M D Cambridge, M assachusetts Coughing in childhood is a common complaint involving a wide spectrum of underlying causes which require a thorough and rational approach by the physician. Most children who cough have relatively simple self-limiting viral infections, but some may have serious disease. A dry environment, allergic factors, cystic fibrosis, and other major illnesses must always be excluded. A simple clinical approach, and the sensible use of appropriate investigations, is most likely to succeed in finding the cause, which can allow precise management. The cough reflex as part of the defense mechanism of the respiratory tract is initiated by mucosal changes, secretions or foreign material in the pharynx, larynx, tracheobronchial Table 1. Persistent Cough — Causes in Childhood* tree, pleura, or ear. Acting as the “watchdog of the lungs,” the “good” cough prevents harmful agents from Common Uncommon Rare entering the respiratory tract; it also helps bring up irritant material from Environmental Overheating with low humidity the airway. The “bad” cough, on the Allergens other hand, serves no useful purpose Pollution Tobacco smoke and, if persistent, causes fatigue, keeps Upper Respiratory Tract the child (and parents) awake, inter Recurrent viral URI Pertussis Laryngeal stridor feres with feeding, and induces vomit Rhinitis, Pharyngitis Echo 12 Vocal cord palsy Allergic rhinitis Nasal polyp Vascular ring ing. It is best suppressed. Coughs and Prolonged use of nose drops Wax in ear colds constitute almost three quarters Sinusitis of all illness in young children. The Lower Respiratory Tract Asthma Cystic fibrosis Rt. -

Chest Pain in a Patient with Cystic Fibrosis

Copyright ©ERS Journals Ltd 1998 Eur Respir J 1998; 12: 245–247 European Respiratory Journal DOI: 10.1183/09031936.98.12010245 ISSN 0903 - 1936 Printed in UK - all rights reserved CASE FOR DIAGNOSIS Chest pain in a patient with cystic fibrosis D.P. Dunagan*, S.L. Aquino+, M.S. Schechter**, B.K. Rubin**, J.W. Georgitis** Case history A 38 yr old female with a history of cystic fibrosis (CF) presented to an outside emergency department with dysp- noea and right-sided chest pain of approximately 12 h duration. Her history was significant for recurrent pneu- mothoraces and a recent respiratory exacerbation of CF requiring prolonged antibiotic therapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa. She described the pain as relatively acute in onset, sharp, increased with deep inspiration, without out- ward radiation, and progressive in intensity. There was no history of travel, worsening cough, fever, chills or increase in her chronic expectoration of blood-streaked sputum. An outside chest radiograph was interpreted as demonstrating a "rounded" right lower lobe pneumonia and she was transferred to our institution for further evaluation. Fig. 2. – Computed tomography scan of the chest. Open arrow: multi- On examination, she was thin, afebrile and in minimal ple cysts; closed white arrow: 3.8×5 cm round mass, respiratory distress. There were decreased breath sounds throughout all lung fields, symmetric chest wall excursion with inspiration and bilateral basilar crackles. Subjective right lateral chest discomfort was reported with deep ins- piratory manoeuvres. The remaining physical examination was normal except for clubbing of the upper extremities. Laboratory data revealed an elevated white blood cell count of 19.2×109 cells·L-1 with a normal differential. -

Respiratory Failure

Respiratory Failure Phuong Vo, MD,* Virginia S. Kharasch, MD† *Division of Pediatric Pulmonary and Allergy, Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA †Division of Respiratory Diseases, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA Practice Gap The primary cause of cardiopulmonary arrest in children is unrecognized respiratory failure. Clinicians must recognize respiratory failure in its early stage of presentation and know the appropriate clinical interventions. Objectives After completing this article, readers should be able to: 1. Recognize the clinical parameters of respiratory failure. 2. Describe the respiratory developmental differences between children and adults. 3. List the clinical causes of respiratory failure. 4. Review the pathophysiologic mechanisms of respiratory failure. 5. Evaluate and diagnose respiratory failure. 6. Discuss the various clinical interventions for respiratory failure. WHAT IS RESPIRATORY FAILURE? Respiratory failure is a condition in which the respiratory system fails in oxy- genation or carbon dioxide elimination or both. There are 2 types of impaired gas exchange: (1) hypoxemic respiratory failure, which is a result of lung failure, and (2) hypercapnic respiratory failure, which is a result of respiratory pump failure (Figure 1). (1)(2) In hypoxemic respiratory failure, ventilation-perfusion (V_ =Q)_ mismatch results in the decrease of PaO2) to below 60 mm Hg with normal or low PaCO2. _ = _ (1) In hypercapnic respiratory failure, V Q mismatch results in the increase of AUTHOR DISCLOSURE Drs Vo and Kharasch fi PaCO2 to above 50 mm Hg. Either hypoxemic or hypercapnic respiratory failure have disclosed no nancial relationships can be acute or chronic. Acute respiratory failure develops in minutes to hours, relevant to this article. -

Cardiology 1

Cardiology 1 SINGLE BEST ANSWER (SBA) a. Sick sinus syndrome b. First-degree AV block QUESTIONS c. Mobitz type 1 block d. Mobitz type 2 block 1. A 19-year-old university rower presents for the pre- e. Complete heart block Oxford–Cambridge boat race medical evaluation. He is healthy and has no significant medical history. 5. A 28-year-old man with no past medical history However, his brother died suddenly during football and not on medications presents to the emergency practice at age 15. Which one of the following is the department with palpitations for several hours and most likely cause of the brother’s death? was found to have supraventricular tachycardia. a. Aortic stenosis Carotid massage was attempted without success. b. Congenital long QT syndrome What is the treatment of choice to stop the attack? c. Congenital short QT syndrome a. Intravenous (IV) lignocaine d. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) b. IV digoxin e. Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome c. IV amiodarone d. IV adenosine 2. A 65-year-old man presents to the heart failure e. IV quinidine outpatient clinic with increased shortness of breath and swollen ankles. On examination his pulse was 6. A 75-year-old cigarette smoker with known ischaemic 100 beats/min, blood pressure 100/60 mmHg heart disease and a history of cardiac failure presents and jugular venous pressure (JVP) 10 cm water. + to the emergency department with a 6-hour history of The patient currently takes furosemide 40 mg BD, increasing dyspnoea. His ECG shows a narrow complex spironolactone 12.5 mg, bisoprolol 2.5 mg OD and regular tachycardia with a rate of 160 beats/min. -

Association Between Finger Clubbing and Chronic Lung Disease in Hiv Infected Children at Kenyatta National Hospital J

342 EAST AFRICAN MEDICAL JOURNAL November 2013 East African Medical Journal Vol. 90 No. 11 November 2013 ASSOCIATION BETWEEN FINGER CLUBBING AND CHRONIC LUNG DISEASE IN HIV INFECTED CHILDREN AT KENYATTA NATIONAL HOSPITAL J. J. Odionyi, MBChB, MMed (Paeds), C. A. Yuko-Jowi, MBChB, MMed (Paeds, Paediatric Cardiology), Senior Lecturer, D. Wamalwa, MBChB, MMed (Paeds), MPH, Senior Lecturer, N. Bwibo, MBChB, MPH, FAAP, MRCP, Professor, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Nairobi, Nairobi and E. Amukoye, MBChB, MMed (Paed), Critical Care, Paediatric Bronchoscopy/Respiratory, Senior Research Officer, Centre for Respiratory Disease Research, Kenya Medical Research Institute, P. O. Box 54840-00202, Nairobi, Kenya Request for reprints to: Dr. J.J. Odionyi, P. O. Box 102299-00101, Nairobi, Kenya ASSOCIATION BETWEEN FINGER CLUBBING AND CHRONIC LUNG DISEASE IN HIV INFECTED CHILDREN AT KENYATTA NATIONAL HOSPITAL J. J. ODIONYI, C. A. YUKO-JOWI, D. WAMALWA, N. BWIBO and E. AMUKOYE ABSTRACT Background: Finger clubbing in HIV infected children is associated with pulmonary diseases. Respiratory diseases cause great morbidity and mortality in HIV infected children. Objective: To determine association between finger clubbing and chronic lung diseases in HIV infected children and their clinical correlates (in terms of WHO clinical staging, CD4 counts/ percentage, anti-retroviral therapy duration and pulmonary hypertension). Design: Hospital based case control study. Setting: The Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH) comprehensive care clinic (CCC) for HIV infected children and Paediatric General Wards. Subjects: The study population comprised of HIV infected children and adolescents aged eighteen years and below. Results: Chronic lung disease was more common among finger clubbed (55%) than non finger clubbed patients (16.7%). -

Lung Crackles in Bronchiectasis

Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.35.9.694 on 1 September 1980. Downloaded from Thorax, 1980, 35, 694-699 Lung crackles in bronchiectasis A R NATH AND L H CAPEL From Harefield Hospital, Middlesex and the London Chest Hospital, London ABSTRACT The inspiratory timing of lung crackles in patients with bronchiectasis was compared with the inspiratory timing of the lung crackles in chronic bronchitis and alveolitis. In severe obstructive chronic bronchitis the lung crackles are typically confined to early inspiration while in alveolitis the lung crackles continue to the end of inspiration but may begin in the early or the mid phase of inspiration. In uncomplicated bronchiectasis on the other hand, the lung crackles typically occur in the early and mid phase of inspiration, are more profuse, and usually fade by the end of inspiration. In addition in bronchiectasis, crackles are also usually present in expiration, they are gravity independent and become less profuse after coughing. Lung crackles in inspiration and expiration can be this group. Three patients had been moderate timed precisely by the simultaneous recording of smokers at some time in the past. Their chest lung sounds and airflow. Forgacs' pointed out that radiographs did not show diffuse lung changes the lung crackles of fibrosing alveolitis typically and the mean FEV1/VC ratio for the group was occur late in inspiration and suggested that these 71% (table 1). The diagnosis of bronchiectasis in sounds coincide with the late opening of the per- each patient was confirmed by bronchogram. copyright. ipheral airways in this condition. Nath and Capel2 contrasted the characteristically late timing of CHRONIC BRONCHITIS inspiratory crackles of fibrosing alveolitis and re- Twelve patients with the clinical features of many lated disorders with the characteristically early years of cough, expectoration and breathlessness timing of the inspiratory crackles in severe ob- were included in this group. -

Postgraduate Examination Skills: Clubbing

Postgraduate Examination Skills: Clubbing Introduction The original description of clubbing was by Hippocrates in the fifth century B.C. in a patient with empyema. Clubbing came into the spotlight again in the 19th century when Eugen Bamberger and Pierre Marie described hypertrophic osteoarthropathy which is a frequently concomitant disorder. By the end of World War I clubbing was known to most physicians, usually as an indicator of chronic infection (Mangione, 2000). Clubbing, the focal enlargement of the connective tissue in the terminal phalanges, is associated with a plethora of infectious, neoplastic, inflammatory and vascular conditions and the diagnostic implications of this sign are such that its presence should not go unnoticed or uninvestigated (see fig.1). As well as being associated with a host of conditions, in a paediatric setting, clubbing can indicate chronic conditions like cystic fibrosis or cyanotic forms of congenital heart disease. However it is also important to remember that clubbing can be a benign sporadic hereditary condition (Myers and Farquhar, 2001). Clinical Anatomy and Pathophysiology The dorsal portion of the distal phalanges are covered by a protective hard keratin cover, the nail plate. This is formed by nail matrix at the proximal end of the nail plate, creating the superficial layers whilst the nail matrix at the distal end creates the deeper layers. Any impairment in this production causes a distortion of the nail. For example disruption of production at the proximal end leads to superficial nail problems such as psoriatic pitting, and disruption of production at the distal end leads to deeper problems like ridging of the nail. -

Chest Pain and Cardiac Dysrhythmias

Chest Pain and Cardiac Dysrhythmias Questions 1. A 59-year-old man presents to the emergency department (ED) com- plaining of new onset chest pain that radiates to his left arm. He has a his- tory of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and a 20-pack-year smoking history. His electrocardiogram (ECG) is remarkable for T-wave inversions in the lateral leads. Which of the following is the most appropriate next step in management? a. Give the patient two nitroglycerin tablets sublingually and observe if his chest pain resolves. b. Place the patient on a cardiac monitor, administer oxygen, and give aspirin. c. Call the cardiac catheterization laboratory for immediate percutaneous inter- vention (PCI). d. Order a chest x-ray; administer aspirin, clopidogrel, and heparin. e. Start a β-blocker immediately. 2. A 36-year-old woman presents to the ED with sudden onset of left- sided chest pain and mild shortness of breath that began the night before. She was able to fall asleep without difficulty but woke up in the morning with persistent pain that is worsened upon taking a deep breath. She walked up the stairs at home and became very short of breath, which made her come to the ED. Two weeks ago, she took a 7-hour flight from Europe and since then has left-sided calf pain and swelling. What is the most com- mon ECG finding for this patient’s presentation? a. S1Q3T3 pattern b. Atrial fibrillation c. Right-axis deviation d. Right-atrial enlargement e. Tachycardia or nonspecific ST-T–wave changes 1 2 Emergency Medicine 3. -

Evaluation of Chest Pain in the Young Adult

Evaluation of Chest Pain in the Young Adult Donald F. Kreuz, MD FACC Columbia Health Columbia University New York, NY 1 Outline • Case Presentation • Chest Pain & Etiologies – Cardiovascular Disorders – Pulmonary Disorders – Gastro-intestinal Disorders – Chest Wall Disorders – Psychiatric/Psychogenic Disorders • Case Review • Summary 2 Cases 3 Case 1 • General – 22yo, Man c/o L-sided chest pain x 1 day • Present Illness – Yesterday, c/o CP after standing up to leave class. • Pain was sharp and severe but did not affect his breathing except if he took a deep breath. • No sweating or dizziness. No prior episodes. • Took a cab home to Bronx and slept. – Today, feels a little better but still has the L-sided chest pain. 4 Case 1 • Pertinent History – Medications: none – Past Medical/Mental Health: none – Surgery/Procedures/Hospitalization: none – Social History • Denies smoking, drug-use • Alcohol use - couple/month • Exercise - Does not do much exercise. 6-8 hours/day on computer. 5 Case 1 • Physical Examination – Vital Signs: • BP = 106/64 Right Arm; Pulse rate =73/min; RR = 16/min • Temp = 96.1 F • Pulse Oximetry/O2 Sat = 98% • Height = 5’ 11.5”; Weight = 140lbs; BMI = 19.3 – Chest/Lung • Normal, no reproducible tenderness – Heart/Vascular: • Regular rate and rhythm, No murmur • Full symmetric pulses 6 Case 2 • General – 24yo Woman c/o ear problem (“clogged”) x 1 month and “muscle ache in my heart” x 1 day • Present Illness – 2 days ago, c/o L-sided chest achy sensation after biking fast. – Yesterday, c/o SOB, cough and then chest pain. • Anterior to posterior over left chest, sometimes left shoulder pain.