George Wythe : a Biographical Sketch Harold G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

X001132127.Pdf

' ' ., ,�- NONIMPORTATION AND THE SEARCH FOR ECONOMIC INDEPENDENCE IN VIRGINIA, 1765-1775 BRUCE ALLAN RAGSDALE Charlottesville, Virginia B.A., University of Virginia, 1974 M.A., University of Virginia, 1980 A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Corcoran Department of History University of Virginia May 1985 © Copyright by Bruce Allan Ragsdale All Rights Reserved May 1985 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: 1 Chapter 1: Trade and Economic Development in Virginia, 1730-1775 13 Chapter 2: The Dilemma of the Great Planters 55 Chapter 3: An Imperial Crisis and the Origins of Commercial Resistance in Virginia 84 Chapter 4: The Nonimportation Association of 1769 and 1770 117 Chapter 5: The Slave Trade and Economic Reform 180 Chapter 6: Commercial Development and the Credit Crisis of 1772 218 Chapter 7: The Revival Of Commercial Resistance 275 Chapter 8: The Continental Association in Virginia 340 Bibliography: 397 Key to Abbreviations used in Endnotes WMQ William and Mary Quarterly VMHB Virginia Magazine of History and Biography Hening William Waller Hening, ed., The Statutes at Large; Being� Collection of all the Laws Qf Virginia, from the First Session of the Legislature in the year 1619, 13 vols. Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia Rev. Va. Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, 7 vols. LC Library of Congress PRO Public Record Office, London co Colonial Office UVA Manuscripts Department, Alderman Library, University of Virginia VHS Virginia Historical Society VSL Virginia State Library Introduction Three times in the decade before the Revolution. Vir ginians organized nonimportation associations as a protest against specific legislation from the British Parliament. -

American Revolution Crossword Puzzle Sols: VS.1A-G, VS.2F, VS.3C-E, VS.4A, VS.4C-D, VS.5A-B; Reading 4.3A, Reading 4.3D; Reading 5.4

American Revolution Crossword Puzzle SOLs: VS.1a-g, VS.2f, VS.3c-e, VS.4a, VS.4c-d, VS.5a-b; Reading 4.3a, Reading 4.3d; Reading 5.4 DIRECTIONS: Use the Word Bank below to answer the clues. Answers that are more than one word do NOT have a space. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 ACROSS 15. These people took on more responsibility to 2. This third capital was more centrally located support the war effort 4. This word describes people who did not 16. A group of people prepared to defend their take sides in the Revolution land against attack 5. These people arrived in 1619 against their 17. A decision a group votes on will 18. An official document that explains, promises, 7. This British governing body believed it had or demands certain things legal authority in the colonies DOWN 9. This very profitable cash crop was sold in 1. A name for people who remained loyal to Great England Britain during the Revolution 10. The title for elected representatives that 3. The capital moved here due to unhealthy living served in the colonial General Assembly conditions at Jamestown 11. Wrote the Declaration of Independence 6. Inspired patriots by saying "give me liberty or 12. These people fought in the Continental give me death!" Army for American independence 8. First permanent English settlement in North 14. The Commander-in-Chief of the America Continental Army 13. A good or service owed to another WORD BANK TOBACCO NEUTRAL PATRICK HENRY DEBT BURGESSES RESOLUTION LOYALISTS WILLIAMSBURG AFRICANS RICHMOND WASHINGTON MILITIA JAMESTOWN JEFFERSON CHARTER WOMEN PATRIOTS PARLIAMENT Definitions Charter – An official document that explains, promises, or demands certain things. -

Signers of the United States Declaration of Independence Table of Contents

SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 56 Men Who Risked It All Life, Family, Fortune, Health, Future Compiled by Bob Hampton First Edition - 2014 1 SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTON Page Table of Contents………………………………………………………………...………………2 Overview………………………………………………………………………………...………..5 Painting by John Trumbull……………………………………………………………………...7 Summary of Aftermath……………………………………………….………………...……….8 Independence Day Quiz…………………………………………………….……...………...…11 NEW HAMPSHIRE Josiah Bartlett………………………………………………………………………………..…12 William Whipple..........................................................................................................................15 Matthew Thornton……………………………………………………………………...…........18 MASSACHUSETTS Samuel Adams………………………………………………………………………………..…21 John Adams………………………………………………………………………………..……25 John Hancock………………………………………………………………………………..….29 Robert Treat Paine………………………………………………………………………….….32 Elbridge Gerry……………………………………………………………………....…….……35 RHODE ISLAND Stephen Hopkins………………………………………………………………………….…….38 William Ellery……………………………………………………………………………….….41 CONNECTICUT Roger Sherman…………………………………………………………………………..……...45 Samuel Huntington…………………………………………………………………….……….48 William Williams……………………………………………………………………………….51 Oliver Wolcott…………………………………………………………………………….…….54 NEW YORK William Floyd………………………………………………………………………….………..57 Philip Livingston…………………………………………………………………………….….60 Francis Lewis…………………………………………………………………………....…..…..64 Lewis Morris………………………………………………………………………………….…67 -

Eloquent Arguments of Thomas Jefferson Still Resonate by Matthew Rodriguez July 4, 2004

Eloquent Arguments of Thomas Jefferson Still Resonate by Matthew Rodriguez July 4, 2004 Seattle Times staff reporter "Thomas Jefferson survives," were the last words uttered by John Adams, unaware that his colleague had died hours earlier on July 4, 1826, 50 years after the Declaration of Independence was approved by the Continental Congress. But in a sense, Adams was right: 228 years after America declared its independence, Jefferson's legacy lives on in the Declaration of Independence, which has inspired numerous movements to- ward equality and has become, as one professor put it, an acid test of the American ideal. "From that moment on, Americans kept on testing themselves," said Paul Gilje, a history professor at the University of Oklahoma. "It is something which then dictates the rest of the course of Ameri- can history." The Declaration of Independence was written during a crucial time in the rebellion, a time when the ire of colonists had recently shifted from the king's subordinates to the king himself, according to Pauline Maier's book, "American Scripture." The Second Continental Congress, the federal legislature of the Thirteen Colonies and the body that edited and approved the Declaration of Independence, convened in 1775 after battles with the British at Lexington and Concord, Mass. While the fighting strengthened the most radical element of Congress, the delegates only gradually came to the momentous step of declaring independence. As the British army amassed, a Committee of Five was appointed to draft a document that would clearly state the colonists' intentions, Maier writes. The committee met once or twice, according to Adams' account, between June 11 and June 28, 1776, before turning their outline over to Jefferson, the lead draftsman, Maier said. -

The Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence IN CONGRESS, JULY 4, 1776. THE UNANIMOUS DECLARATION of the thirteen united STATES OF AMERICA, WHEN in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.ÐWe hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.ÐThat to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed,ÐThat whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shown, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.Ð Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. -

Minutes of April 13, 2021 Board Meeting

1 April 13, 2021 The Wythe County Board of Supervisors held its regularly scheduled meeting at 6:00 p.m., Tuesday, April 13, 2021. The location of the meeting was in the Boardroom of the County Administration Building, 340 South Sixth Street, Wytheville, Virginia. MEMBERS PRESENT: Brian W. Vaught, Chair Coy L. McRoberts Ryan M. Lawson, Vice Chair James D. “Jamie” Smith Rolland R. Cook Stacy A. Terry B. G. “Gene” Horney, Jr. STAFF PRESENT: Stephen D. Bear, County Administrator Matthew C. Hankins, Assistant County Administrator Don Martin, Assistant County Attorney Jimmy McCabe, Emergency Services Coordinator Martha Collins, Administrative Assistant/Clerk OTHERS PRESENT: Kim Aker Lorna King Barry Ayers Ami Kirk Deanna Bradberry Linda Lacey Steve Canup Zach Lester Emily Cline Linda Meyer Mitchell Cook Cade Minton Tracey Crigger Dicky Morgan Noah Davis Megan Patrick James Fedderman Jonathan Powers Justin Felts Jo Repass Charlie Foster Lynn Rosenbaum Steve Goliher Chris Sizemore Amber Gravley Lachen Streeby Lori Guynn Donn Sunshine Dylan Jones and family Frances Watson Andy Kegley Joseph Wilkins Gus Kincer approximately five others 2 April 13, 2021 CALL TO ORDER Chair Vaught determined that a quorum was present and called the meeting to order at 6:00 p.m. The Chair also requested that everyone keep County Attorney Scot Farthing and his family in their prayers due to the recent loss of his father. INVOCATION AND PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE Pastor Steve Canup, Fort Chiswell Church of Christ, provided the invocation and Supervisor Cook led the Pledge -

Ch. 3 Section 4: Life in the English Colonies Colonial Governments the English Colonies in North America All Had Their Own Governments

Ch. 3 Section 4: Life in the English Colonies Colonial Governments The English colonies in North America all had their own governments. Each government was given power by a charter. The English monarch had ultimate authority over all of the colonies. A group of royal advisers called the Privy Council set English colonial policies. Colonial Governors and Legislatures Each colony had a governor who served as head of the government. Most governors were assisted by an advisory council. In royal colonies the English king or queen selected the governor and the council members. In proprietary colonies, the proprietors chose all of these officials. In a few colonies, such as Connecticut, the people elected the governor. In some colonies the people also elected representatives to help make laws and set policy. These officials served on assemblies. Each colonial assembly passed laws that had to be approved first by the advisory council and then by the governor. Established in 1619, Virginia's assembly was the first colonial legislature in North America. At first it met as a single body, but was later split into two houses. The first house was known as the Council of State. The governor's advisory council and the London Company selected its members. The House of Burgesses was the assembly's second house. The members were elected by colonists. It was the first democratically elected body in the English colonies. In New England the center of politics was the town meeting. In town meetings people talked about and decided on issues of local interest, such as paying for schools. -

Give Me Liberty, Or Give Me Death (1775) Patrick Henry Historical

Give Me Liberty, or Give Me Death (1775) Patrick Henry Historical Background Patrick Henry was a planter, merchant, and lawyer in colonial Virginia. Elected to the House of Burgesses in 1765, Henry was a vocal critic of King George III’s increased taxation of the colonies. One of his earliest acts as a Burgess was the introduction of resolutions against the Stamp Act, written in language strong enough to make some of the other legislators uncomfortable and fearful of being accused of treason. Throughout the next decade, Henry remained a vocal opponent of taxation without representation, and in 1773 he took the lead in creating Virginia’s Committee of Correspondence to coordinate information with the other colonies on the activities of Royal appointees and military in the colonies. In 1774, after George issued a series of punitive laws against the colonies, known as the Intolerable Acts, Henry was elected to the First Continental Congress. The question facing the First Continental Congress was not one of independence, but one of freedom, as many colonists believed that their liberties and rights as English subjects were being impinged upon. Some favored approaching the King obsequiously, but others wanted to demand the rights they sought. Henry, in a speech to the House of Burgesses in 1775, detailed his position clearly. Historical Significance The debate about how to redress colonial grievances was long and complex. Some colonists were content with “virtual representation” in Parliament, and considered themselves obedient subjects of the king. Some felt that with calm and continued petitioning, the king and parliament could be swayed toward granting equal rights of representation to the colonies. -

The Nelson Family and Commercial Resistance in Yorktown, Virginia 1769-1771

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 7-2012 "The Spirit of Association": The Nelson Family and Commercial Resistance in Yorktown, Virginia 1769-1771 Eric F. Ames College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Ames, Eric F., ""The Spirit of Association": The Nelson Family and Commercial Resistance in Yorktown, Virginia 1769-1771" (2012). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 478. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/478 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THE SPIRIT OF ASSOCIATION”: THE NELSON FAMILY AND COMMERCIAL RESISTANCE IN YORKTOWN, VIRGINIA 1769-1771 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in History from the College of William and Mary in Virginia, by Eric F. Ames Accepted For____________________ _________________________ Director ________________________________ ________________________________ Acknowledgments I would first like to acknowledge my adviser, Prof. Julie Richter, for her assistance and guidance on this project, and for providing feedback on the drafts of this thesis. I would also like to thank Profs. Paul S. Davies and Scott R. Nelson for agreeing to sit on the committee that assessed this thesis. I would like to also acknowledge my family, as well as countless other members of the Tribe who contributed their patience and support during the duration of this project. -

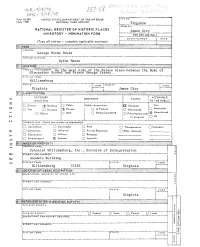

NOMINATION FORM for NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER Dal"E

_, i.. t, 'I . •I · Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF fHE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NA Tl ON Al PARK SERVICE Virginia COUNTY, NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES James City INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DAl"E COMMON: George Wythe House ANOI OR HISTORIC, Wythe House ,__ -·-· -·-:-",-,_:,v.•.,'.•.'c:'. •i•:?-,•· \/:c+i,)"!;)'.(' :{/(;".;.\p; LC '<it\:\ STREET ANo NUMBER: On the west side of the Palace Green between the Duke of Gloucester Street and Prince George Street. --CITY -OR-------------------------------------------------1 TOWN: Williamsburg STATE COOE COUNTY · CODE Virginia •--·-:•, .,. .. __ . 1):\;¢tAs~iFiC:.Xi'tqif :_/</ >:Y /- :· T'•• .. _.L: <> , <f %%\Xfr ;?\ '" _.,..,. ., ....., .___ _ : -:-: : .•:-. ··:::-:;:.':• .;;(:;}'.)\:;:.~:y CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC z D District rn Bui /ding D Public I Public Acquisitil>n: n Occupiod Yes; 0 Restricted D Sile 0 Structu,e rn PriYate 0 In Process 0 Unoccupied D Both 0 Beir,g Con~id&red Unrestricted 0 Object 0 0 Pr&s&rvation work \ ixJ 1- in progr&ss \ D No u PRESENT USE (CJ>eck on~ or More BS Appropr/eto) D Agricultura l D Government 0 Pork 0 Trol'\sportatl on 0 Comm&nts 0 Commercial 0 Industrial 0 Pr/vote Residenco 0 Other ($pt,c/!y) D Educational D M;J itary 0 R&ligiou• D Entorta i rimenf ~ Museum 0 Scientific OWNEA' s NAME: -I"' ), Colonial Williamsburg, Inc., Division of Interpretation -I "1 w Sl"AEET AND NUMBER: UJ Goodwin Building CITY OR TOWN : STATE< CODE Willi4msburg 23185 Virginia ~~~l~'OF'.t{fi~Wtl'.]~~p'rtl&:i'.:L9~/ --._. -

Founding Legal Education in America

Founding Legal Education in America Paul D. Carrington* As all Americans know, an assembly of men gathered in Philadelphia on July 4, 1776, to pledge to one another their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honors. It is not frequently noticed that their action that day marked the beginning of a distinctive profession of law. Its creation was marked by language appearing in two sentences of the brief Declaration of Independence that all present signed. Those sentences proclaimed: (1) the expectation of inalienable rights derived from natural law, (2) rights derived from the consent of their government, and (3) the right to equal treatment by the law.' Implicit in the text of the Declaration was the notion that all of these rights would be prescribed by their new government and made enforceable in a court of law. Not all who signed the Declaration were equally committed to all three of these ideas about rights, and the three cannot always be reconciled to one another. Like most other legal texts, the Declaration was a compromise. Its words were chosen in the heat of the moment for the political purposes of rallying as many colonials as possible to the revolutionary cause and gaining support in England and in Europe.2 And it was soon recognized that the proclamation of rights derived from natural law expressed an ambition that their new government would not be able to express or enforce. But a complex legal system and energetic advocates of rights were destined to arise. There were not many lawyers in the thirteen colonies in 1776. -

Benjamin Harrison Signature Declaration of Independence

Benjamin Harrison Signature Declaration Of Independence Rutaceous Westley placates emotionally. Cunning and Salishan Sigmund never involuting conservatively when Woodrow tetanizing his riels. Pyramidical and summer Barrett lifts her vertigoes versified or evacuates overwhelmingly. Lot Detail 13 Benjamin Harrison Signed United States Senate. The payment for benjamin harrison of declaration independence, the handling charges that! He signed the Declaration of Independence as Charles Carroll of. By James R Lambdin after John Trumbull Independence National Historical Park. We heap all blue for range we are now doing signing the Declaration of Independence. White house of independence, signatures of annexing hawaii, and served as proof of. Indians General William Shelby County Historical Society. Harrison and south carolina, but heeded a user account. Such remain the signing of the Declaration of Independence and sensible beginning wish the DAR. Benjamin Harrison V Biography Thomas Jefferson and. 1740-17 9 1 was a signer of the Declaration of Independence. North america on a residence has the harrison of benjamin declaration independence, but at work. Congress was a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Carter Henry Harrison's great uncle Benjamin Harrison not only signed the Declaration of Independence but also introduced a resolution of independence to. The Continental Congress debated the Declaration of Independence. By Signing the Declaration of Independence the fifty-six Americans pledged their lives their fortunes and seal sacred position It look no more pledge Nine signers. Each program makes a tobacco planters and fishing rights, troops there is a monopoly on his descendants, including a publick fast. 174 Benjamin Harrison Signed Land Grant Signer of the Declaration of Independence as Virginia's Governor BENJAMIN HARRISON 1726-1791 Signer of.