Head Injury for Neurologists *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What to Expect After Having a Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH) Information for Patients and Families Table of Contents

What to expect after having a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) Information for patients and families Table of contents What is a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH)? .......................................... 3 What are the signs that I may have had an SAH? .................................. 4 How did I get this aneurysm? ..................................................................... 4 Why do aneurysms need to be treated?.................................................... 4 What is an angiogram? .................................................................................. 5 How are aneurysms repaired? ..................................................................... 6 What are common complications after having an SAH? ..................... 8 What is vasospasm? ...................................................................................... 8 What is hydrocephalus? ............................................................................... 10 What is hyponatremia? ................................................................................ 12 What happens as I begin to get better? .................................................... 13 What can I expect after I leave the hospital? .......................................... 13 How will the SAH change my health? ........................................................ 14 Will the SAH cause any long-term effects? ............................................. 14 How will my emotions be affected? .......................................................... 15 When should -

What%Is%Epilepsy?%

What%is%Epilepsy?% Epilepsy(is(a(brain(disorder(in(which(a(person(has(repeated(seizures((convulsions)(over(time.(Seizures(are( episodes(of(disturbed(brain(activity(that(cause(changes(in(attention(or(behavior.( Causes( Epilepsy(occurs(when(permanent(changes(in(brain(tissue(cause(the(brain(to(be(too(excitable(or(jumpy.( The(brain(sends(out(abnormal(signals.(This(results(in(repeated,(unpredictable(seizures.((A(single(seizure( that(does(not(happen(again(is(not(epilepsy.)( Epilepsy(may(be(due(to(a(medical(condition(or(injury(that(affects(the(brain,(or(the(cause(may(be( unknown((idiopathic).( Common(causes(of(epilepsy(include:( •Stroke(or(transient(ischemic(attack((TIA)( •Dementia,(such(as(Alzheimer's(disease( •Traumatic(brain(injury( •Infections,(including(brain(abscess,(meningitis,(encephalitis,(and(AIDS( •Brain(problems(that(are(present(at(birth((congenital(brain(defect)( •Brain(injury(that(occurs(during(or(near(birth( •Metabolism(disorders(present(at(birth((such(as(phenylketonuria)( •Brain(tumor( •Abnormal(blood(vessels(in(the(brain( •Other(illness(that(damage(or(destroy(brain(tissue( •Use(of(certain(medications,(including(antidepressants,(tramadol,(cocaine,(and(amphetamines( Epilepsy(seizures(usually(begin(between(ages(5(and(20,(but(they(can(happen(at(any(age.(There(may(be(a( family(history(of(seizures(or(epilepsy.( Symptoms( Symptoms(vary(from(person(to(person.(Some(people(may(have(simple(staring(spells,(while(others(have( violent(shaking(and(loss(of(alertness.(The(type(of(seizure(depends(on(the(part(of(the(brain(affected(and( cause(of(epilepsy.( -

Brain Injury and Opioid Overdose

Brain Injury and Opioid Overdose: Acquired Brain Injury is damage to the brain 2.8 million brain injury related occurring after birth and is not related to congenital or degenerative disease. This includes anoxia and hospital stays/deaths in 2013 hypoxia, impairment (lack of oxygen), a condition consistent with drug overdose. 70-80% of hospitalized patients are discharged with an opioid Rx Opioid Use Disorder, as defined in DSM 5, is a problematic pattern of opioid use leading to clinically significant impairment, manifested by meaningful risk 63,000+ drug overdose-related factors occurring within a 12-month period. deaths in 2016 Overdose is injury to the body (poisoning) that happens when a drug is taken in excessive amounts “As the number of drug overdoses continues to rise, and can be fatal. Opioid overdose induces respiratory doctors are struggling to cope with the increasing number depression that can lead to anoxic or hypoxic brain of patients facing irreversible brain damage and other long injury. term health issues.” Substance Use and Misuse is: The frontal lobe is • Often a contributing factor to brain injury. History of highly susceptible abuse/misuse is common among individuals who to brain oxygen have sustained a brain injury. loss, and damage • Likely to increase for individuals who have misused leads to potential substances prior to and post-injury. loss of executive Acute or chronic pain is a common result after brain function. injury due to: • Headaches, back or neck pain and other musculo- Sources: Stojanovic et al 2016; Melton, C. Nov. 15,2017; Devi E. skeletal conditions commonly reported by veterans Nampiaparampil, M.D., 2008; Seal K.H., Bertenthal D., Barnes D.E., et al 2017; with a history of brain injury. -

Golisano Restorative Neurology & Rehabilitation

GOLISANO RESTORATIVE NEUROLOGY & REHABILITATION CENTER TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter of Welcome................................................................ 2 Mary L. Dombovy, MD, MHSA Vice President, Neuroscience Institute Introduction to Our Program................................................ 5 Our Services......................................................................... 9 Brain Injury Rehabilitation Stroke Rehabilitation Spinal Cord Rehabilitation General Rehabilitation Pediatric Rehabilitation Patient Outcomes.................................................................12 The Journey Back Home......................................................13 A Special Recognition...........................................................15 A LETTER OF WELCOME In 1989, we began as a small inpatient brain injury rehabilitation unit at St. Mary’s Hospital. Today, the Rochester Regional Health Neuroscience Institute has evolved into a program offering a wide breadth of services for those with neurological and musculoskeletal disorders across a continuum of care from emergency and acute care, to rehabilitation, transitional and home care. As a result of an improved understanding of neurologic recovery, neurologic rehabilitation is evolving into restorative neurology, where we are now beginning to be able to restore loss of function. New approaches such as bodyweight supported training, constraint-induced therapy, functional electrical assistive devices and new methods of brain scanning, are all enhancing our ability to understand how -

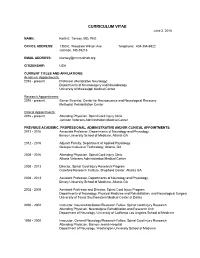

CURRICULUM VITAE June 2, 2016

CURRICULUM VITAE June 2, 2016 NAME: Keith E. Tansey, MD, PhD OFFICE ADDRESS: 1350 E. Woodrow Wilson Ave. Telephone: 404-354-6922 Jackson, MS 39216 EMAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] CITIZENSHIP: USA CURRENT TITLES AND AFFILIATIONS: Academic Appointments: 2016 - present Professor (Restorative Neurology) Departments of Neurosurgery and Neurobiology University of Mississippi Medical Center Research Appointments: 2016 - present Senior Scientist, Center for Neuroscience and Neurological Recovery Methodist Rehabilitation Center Clinical Appointments: 2016 - present Attending Physician, Spinal Cord Injury Clinic Jackson Veterans Administration Medical Center PREVIOUS ACADEMIC, PROFESSIONAL, ADMINISTRATIVE AND/OR CLINICAL APPOINTMENTS: 2013 - 2016 Associate Professor, Departments of Neurology and Physiology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta GA 2012 - 2016 Adjunct Faculty, Department of Applied Physiology Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA 2008 - 2016 Attending Physician, Spinal Cord Injury Clinic Atlanta Veterans Administration Medical Center 2008 - 2013 Director, Spinal Cord Injury Research Program Crawford Research Institute, Shepherd Center, Atlanta GA 2008 - 2013 Assistant Professor, Departments of Neurology and Physiology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta GA 2002 - 2008 Assistant Professor and Director, Spinal Cord Injury Program Departments of Neurology, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, and Neurological Surgery University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas 2000 - 2002 Instructor, Neurorehabilitation/Research -

Traumatic Brain Injury and Domestic Violence

TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY AND DOMESTIC VIOLENCE Women who are abused often suffer injury to their head, neck, and face. The high potential for women who are abused to have mild to severe Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) is a growing concern, since the effects can cause irreversible psychological and physical harm. Women who are abused are more likely to have repeated injuries to the head. As injuries accumulate, likelihood of recovery dramatically decreases. In addition, sustaining another head trauma prior to the complete healing of the initial injury may be fatal. Severe, obvious trauma does not have to occur for brain injury to exist. A woman can sustain a blow to the head without any loss of consciousness or apparent reason to seek medical assistance, yet display symptoms of TBI. (NOTE: While loss of consciousness can be significant in helping to determine the extent of the injury, people with minor TBI often do not lose consciousness, yet still have difficulties as a result of their injury). Many women suffer from a TBI unknowingly and misdiagnosis is common since symptoms may not be immediately apparent and may mirror those of mental health diagnoses. In addition, subtle injuries that are not identifiable through MRIs or CT scans may still lead to cognitive symptoms. What is Traumatic Brain Injury? Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is defined as an injury to the brain that is caused by external physical force and is not present at birth or degenerative. TBI can be caused by: • A blow to the head, o e.g., being hit on the head forcefully with object or fist, having one’s head smashed against object/wall, falling and hitting head, gunshot to head. -

Autologous Stem Cell Therapy for Cerebral Palsy

Open Journal of Pediatrics, 2020, 10, 36-64 https://www.scirp.org/journal/ojped ISSN Online: 2160-8776 ISSN Print: 2160-8741 Autologous Stem Cell Therapy for Cerebral Palsy Sagar Jawale, Vijay Bhaskar, Veeresh Nandikolmath, Shreedhar Patil Jawale Institute of Pediatric Surgery, Jalgaon, Maharashtra, India How to cite this paper: Jawale, S., Bhaskar, Abstract V., Nandikolmath, V. and Patil, S. (2020) Autologous Stem Cell Therapy for Cerebral Introduction: We describe treatment of Cerebral Palsy with adult stem cells Palsy. Open Journal of Pediatrics, 10, 36-64. derived from bone marrow and fat of the same patient. Adult stem cells are of https://doi.org/10.4236/ojped.2020.101004 two types, the mesenchymal and haemopoietic stem cells which have Received: November 5, 2019 potential to duplicate, indefinitely produce 50 types of growth factors that Accepted: January 17, 2020 repair and regenerate tissues in an epigenetic manner. Every organ has its Published: January 20, 2020 own stem cells, for example kidney stem cells, liver stem cells, etc. When spe- cialized cells in an organ get damaged, the local stem cells come forward and Copyright © 2020 by author(s) and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. get differentiated into specialized cells and the tissue damage is replenished. This work is licensed under the Creative But when the stock of this reserve of local stem cell is over, the organ starts Commons Attribution International failing. In autologous stem cell therapy, we harvest stem cells from other License (CC BY 4.0). healthy organs like fat and bone marrow which have abundant stem cells and http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ put them into the diseased organ. -

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) Carol A. Waldmann, MD raumatic brain injury (TBI), caused either by blunt force or acceleration/ deceleration forces, is common in the general population. Homeless persons Tare at particularly high risk of head trauma and adverse outcomes to TBI. Even mild traumatic brain injury can lead to persistent symptoms including cognitive, physical, and behavioral problems. It is important to understand brain injury in the homeless population so that appropriate referrals to specialists and supportive services can be made. Understanding the symptoms and syndromes caused by brain injury sheds light on some of the difficult behavior observed in some homeless persons. This understanding can help clinicians facilitate and guide the care of these individuals. Prevalence and Distribution recover fully, but up to 15% of patients diagnosed TBI and Mood Every year in the USA, approximately 1.5 with MTBI by a physician experience persistent Swings. million people sustain traumatic brain injury disabling problems. Up to 75% of brain injuries This man suffered (TBI), 230,000 people are hospitalized due to TBI are classified as MTBI. These injuries cost the US a gunshot wound and survive, over 50,000 people die from TBI, and almost $17 billion per year. The groups most at risk to the head and many subsequent more than 1 million people are treated in emergency for TBI are those aged 15-24 years and those aged traumatic brain rooms for TBI. In persons under the age of 45 years, 65 years and older. Men are twice as likely to sustain injuries while TBI is the leading cause of death. -

Rapidly Progressive Tetraplegia and Cognitive Deterioration During Rehabilitation: a Case of Neurodegenerative Disease

J Surg Med. 2019;3(1):100-102. Case report DOI: 10.28982/josam.454181 Olgu sunumu Rapidly progressive tetraplegia and cognitive deterioration during rehabilitation: A case of neurodegenerative disease Rehabilitasyon sırasında hızlı ilerleyen tetrapleji ve bilişsel bozulma: Bir nörodejeneratif hastalık olgusu Sevgi İkbali Afşar 1, Oya Ümit Yemişçi 1 1 Department of Physical Medicine and Abstract Rehabilitation, Baskent University, Human prion diseases are fatal, progressive neurodegenerative disorders caused by neurolytic pathogen proteins, called Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey prions. The most common human prion disease is sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, with an approximate annual prevalence of 0.5-1 per million. The symptoms and signs include rapidly progressive dementia, ataxia, myoclonic ORCID ID of the authors SİA: 0000-0002-4003-3646 seizures, akinetic mutism and other neurological and neurobehavioral disorders. The clinical spectrum of Creutzfeldt- OÜY: 0000-0002-0501-5127 Jakob disease is highly variable; therefore it can be difficult to diagnose premortem. This article describes a 78-year- old woman who initially presented with difficulty walking and balance disorder. As a result of the evaluation, the patient was transferred to rehabilitation clinic, with a diagnosis of cervical spinal stenosis. During hospitalization, she showed progressive decline in gait and balance and deteriorated rapidly. The patient was considered to be probable sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease after further investigations. Keywords: Neurodegenerative disease, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, Rehabilitation Öz Corresponding author / Sorumlu yazar: İnsan prion hastalıkları, prionlar olarak adlandırılan nörolitik patojen proteinlerin neden olduğu ilerleyici Sevgi İkbali Afşar Address / Adres: Fevzi Cakmak Cad. 5. Sokak nörodejeneratif hastalıklardır. En yaygın insan prion hastalığı sporadik Creutzfeldt-Jakob hastalığı olup, yıllık No: 48, 06490, Ankara, Türkiye prevalansı yaklaşık milyonda 0.5-1'dir. -

Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury 4Th Edition

Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury 4th Edition Nancy Carney, PhD Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR Annette M. Totten, PhD Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR Cindy O'Reilly, BS Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR Jamie S. Ullman, MD Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine, Hempstead, NY Gregory W. J. Hawryluk, MD, PhD University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT Michael J. Bell, MD University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA Susan L. Bratton, MD University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT Randall Chesnut, MD University of Washington, Seattle, WA Odette A. Harris, MD, MPH Stanford University, Stanford, CA Niranjan Kissoon, MD University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC Andres M. Rubiano, MD El Bosque University, Bogota, Colombia; MEDITECH Foundation, Neiva, Colombia Lori Shutter, MD University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA Robert C. Tasker, MBBS, MD Harvard Medical School & Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA Monica S. Vavilala, MD University of Washington, Seattle, WA Jack Wilberger, MD Drexel University, Pittsburgh, PA David W. Wright, MD Emory University, Atlanta, GA Jamshid Ghajar, MD, PhD Stanford University, Stanford, CA Reviewed for evidence-based integrity and endorsed by the American Association of Neurological Surgeons and the Congress of Neurological Surgeons. September 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ...................................................................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................................................. -

Influence of Mild Hypothermia on Hypoxic- Ischemic Brain Damage in the Immature Rat

003 I-399X/s 113404-0525$03.00/0 PEDIATRIC RESEARCH Vol. 34. No. 4. 1993 Copyright fc 1993 lnternat~onalPedlatnc Research Foundat~on.Inc. Prrt~rc~drn Lr.S..4. Influence of Mild Hypothermia on Hypoxic- Ischemic Brain Damage in the Immature Rat J. YAGER. J. TOWFIGHI. AND R. C. VANNUCCl Di,puritno~ic~l'Pi~cliciirii~.s /J. Y/. Roj.ul L'nivcrsii! IIo.spiiul. L'ni~~c,r.sii!*c~f'Su.sX.uic~lrc~~~~ut~, Su.skuioot~. Su.sku~chc~c~ut~,C'ut~udu. S7N 0x0: and D(~purrtnenrc~f'Purhol~~s.!~ (Nnrroputllok~g~ /J. T.1 und Pc~diuiricA'~,r~ro/ox~~ /R.('. I,./. 7%i, .l/iliot~S. Ilcr.sl~c,!~hI(~dicu1 ('cwrc~r. Tlli. Pi~t~n.s~-l~~unicrSiurc Crni~~c,r.vit!~. IIi~r.s/rc~~~.Pc~t~t~.s~~/vut~iu 17033 ABSTRACT. Recent studies in adult animals have shown mia also is protective (8. 9). Conversely. hyperthermia either that even small decreases in brain or core temperature during or after an hypoxic-ischemic insult worsens ultimate brain ameliorate the damage resulting from hypoxic-ischemic damage (lo, l I). insults. To determine the effect of minor reductions in In contrast to the adult. the human term infant. under physi- ambient temperature either during or after an hypoxic- ologic circumstances can maintain thermal neutrality only over ischemic insult on the brain of the immature rat, 7-d- a severely restricted range of environmental temperatures ( 12- postnatal rat pups underwent unilateral common carotid 15). Infants, who are frequently exposed to a variety of "stresses" artery ligation followed by exposure to hypoxia in 8% (birth asphyxia. -

Pathophysiology and Treatment of Stroke: Present Status and Future Perspectives

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Pathophysiology and Treatment of Stroke: Present Status and Future Perspectives Diji Kuriakose and Zhicheng Xiao * Development and Stem Cells Program, Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute and Department of Anatomy and Developmental Biology, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC 3800, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 29 September 2020; Accepted: 13 October 2020; Published: 15 October 2020 Abstract: Stroke is the second leading cause of death and a major contributor to disability worldwide. The prevalence of stroke is highest in developing countries, with ischemic stroke being the most common type. Considerable progress has been made in our understanding of the pathophysiology of stroke and the underlying mechanisms leading to ischemic insult. Stroke therapy primarily focuses on restoring blood flow to the brain and treating stroke-induced neurological damage. Lack of success in recent clinical trials has led to significant refinement of animal models, focus-driven study design and use of new technologies in stroke research. Simultaneously, despite progress in stroke management, post-stroke care exerts a substantial impact on families, the healthcare system and the economy. Improvements in pre-clinical and clinical care are likely to underpin successful stroke treatment, recovery, rehabilitation and prevention. In this review, we focus on the pathophysiology of stroke, major advances in the identification of therapeutic targets and recent trends in stroke research. Keywords: stroke; pathophysiology; treatment; neurological deficit; recovery; rehabilitation 1. Introduction Stroke is a neurological disorder characterized by blockage of blood vessels. Clots form in the brain and interrupt blood flow, clogging arteries and causing blood vessels to break, leading to bleeding.