Edited by Stig Hjarvard and Mia Lövheim NORDIC PERSPECTIVES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

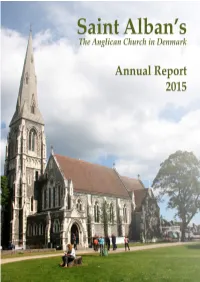

St Albans Annual Report 2015.Pdf

1" ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Contents:((1)(From(the(Chaplain,((1)(The(Chaplaincy(Council,((3)(Ministry(and(Mission(in(Jutland,((4)(Electoral(Roll,((4)(Chaplaincy( Council(Meetings(in(2015,((7)(Churchwardens’(Report,((8)(Registrar’s(Report,((8)(Altar(Guild,((8)(Mothers’(Union,((8)(Music(and( Choir,((9)(Coffee(Team,((10)(Ecumenical(Activities,((12)(Summer(Fête,((12)(The(Guardians’(Team,((12)(The(Sunday(School,((12)( Communications,((14)(Deanery(Synod,((15)(Diocesan(Synod.( ( ( FROM!THE!CHAPLAIN! ( Canon!Barbara!Moss,!who!served!as!Chaplain!in!the!Anglican!Church!in! Gothenburg!until!her!retirement!at!the!end!of!last!year,!used!to!say!that! one!of!the!questions!she!was!most!commonly!asked!by!members!of!the! local!Swedish!Church!was,!“How!many!people!work!at!your!Church?”! To!which!the!redoubtable!Barbara!would!reply,!“Most!of!them!”! ! What!is!true!for!Gothenburg!is!also!true!for!Copenhagen.!Our! extraordinary!Chaplaincy!covers!an!entire!country!(albeit!a!relatively! small!one!)!and!holds!regular!services!in!four!different!locations!(a!couple! of!hundred!miles!apart!).!And!yet,!it!thrives!with!just!one!fullNtime! employee!and!a!veritable!angelic!host!of!volunteers!who!give!of!their!time! and!their!talents!to!sustain!and!grow!Anglican!witness!in!Denmark.! ! ! As!this!Report!shows,!these!wonderful!people!were!especially!busy!in! 2015.!With!large!increases!in!numbers!attending!services,!an!expanding! electoral!roll!and!many!new!initiatives!being!undertaken,!we!have!more! -

Martin Yael Santana Director

Programa de Doctorado de Psicodidáctica: Psicología de la educación y didáctica específicas. Departamento de Psicología Evolutiva y de la Educación LA PERCEPCIÓN DE PREJUICIOS EN LA INMIGRACIÓN DE LOS ESTUDIANTES UNIVERSITARIOS EN SUS SERIES DE FICCIÓN FAVORITAS Autor: Martin Yael Santana Director: Juan Ignacio Martínez de Morentin 2019 (cc)2019 MARTIN YAEL SANTANA MEJIA (cc by-nc 4.0) 1 2 Somos una especie en viaje No tenemos pertenencias sino equipaje Vamos con el polen en el viento Estamos vivos porque estamos en movimiento Nunca estamos quietos, somos trashumantes Somos padres, hijos, nietos y bisnietos de inmigrantes Es más mío lo que sueño que lo que toco… Yo no soy de aquí Pero tú tampoco. JORGE DREXLER (CANTAUTOR). MOVIMIENTO. 3 4 Agradecimientos Al terminar o estar terminando una investigación de estas características sientes un sin número de emociones positivas por ese hecho, el de terminar. Sin embargo, en mi caso creo que una parte de mí no quisiera terminar este trabajo, aunque suene raro. Mucho esfuerzo y dedicación que de no estar presentes muchas personas en mi vida quizás no hubiese ni siquiera comenzado. Estoy y estaré eternamente agradecido con mi director y tutor, acompañándome siempre, con una gran disposición, Juan Ignacio Martínez de Morentin. Mejor tutor no podría existir en todo este cuadrante del universo. Lo que mejor he podido aprender son sus formas de enseñar y espero algún día, siquiera ser un poco como tú. A Conchi Medrano por apoyarme e impulsarme y motivarme desde el master a seguir el camino de la tesis doctoral. A mi familia, especialmente a mi madre y hermana por el apoyo brindado todo este tiempo que me he embarcado a realizar esta investigación. -

School of Mission and Theology Stavanger

SCHOOL OF MISSION AND THEOLOGY STAVANGER Global studies. Intercultural communication. 30-MATH What factors influence the achievements of Muslim Men and Women in tertiary education? Muhammed Mataar Baaba Sillah 2014 1 I This thesis is the apogee of a two year programme of intensive study and research at the School of Mission and Theology in Stavanger, Norway. It is, inter-alia, an embodiment of work and an engagement of the thought of Scholars in and around Norway and the World. It is the assemblage of what young Muslim men and women students who are currently living in Stavanger and are studying, finishing or have just completed their studies at Universities in Norway say about their current situation as students, as descendants of refugees, as immigrants and as practicing adherents of Islam. It is about the challenges they face, their achievements, what they think about each other in relation to a future in matrimonial life, their religion and the future of Islam in Norway. It is a synthesis of all the above and beyond and of course my own insights, perceptions, experience as an older immigrant in Norway who, has traversed many a country and indeed a few continents. I trust that everything that is presented in the pages below will be a true reflection of the views of my respondents. I hasten to add that the sample I have selected might not be a representative sample of views of all Muslim men and women throughout Norway. With this in mind though, I believe that the results of the study will at the very least be instructive in more ways than one and can perhaps be the basis for further studies? It is anticipated that the analysis of the status of the discourse in ‘Men and women in tertiary education will take on board and examine the literature, the facts and figures of the allied nodal issues that have some bearing on policy and the making of a truly multi-cultural Norway. -

Covid-19 and the Islamic Council of Norway: the Social Role of Religious Organizations

Bjørn Hallstein Holte (Oslo) Covid-19 and The Islamic Council of Norway: The Social Role of Religious Organizations Abstract: The new coronavirus came to Norway along with vacationers returning from Italy and Austria in February 2020. In less than a month, the demographic profile of the individuals infected by the virus changed from the privileged to the less privileged and from people born in Norway to immigrants from certain mostly Muslim- majority countries. This article presents how The Islamic Council of Norway (ICN) produced and distributed information material about the coronavirus in the early phase of the pandemic in Norway. Further, it examines how the ICN’s informational material reflects particular ideas about the social role of religious organizations. The empirical material analyzed in the article stems from media reports, government press releases, and information material published online; the analysis is inspired by Niklas Luhmann’s theory of society. The results show dedifferentiation occurring as the ICN linked religion to politics and health as well as how the ICN links the Norwegian national public with a transnational Muslim public. Thus, this article shows how different ideas of the religious and the secular as well as of the national and the transnational coexist in Norway. The discussion relates this to theories about the social role of religion and religious organizations, focusing particularly on the concept of religious organizations as public spaces. The article contributes to a metatheoretical reflection on religious social practice. It also employs and tests alternative theoretical understandings of integration and social cohesion. The results are relevant for practitioners and analysts of religious social practice in modern, secular, and diverse social contexts. -

Dogmer for Tv-Drama

2002: DR vinder Emmy i kategorien ‘Bedste udenlandske dramaserie’ for Rejseholdet (2000-04). Fra venstre: Sven Clausen, Mads Mikkelsen, Charlotte Fich og Peter Thorsboe. Foto: Bax Lindhardt. Dogmer for tv-drama Om brugen af one vision, den dobbelte historie og crossover i DR’s søndagsdramatik A f Eva N ovrup R edvall Danmarks Radio har siden årtusindskiftet plads blandt serier som M ad Men (2007-), haft markant succes med sine lange drama The Walking D ead (2010-) og Breaking serier. Derom vidner både høje seertal Bad (2008-) på kabelkanalen AMC. Tv- søndag efter søndag i kl. 20-slottet og fire serierne er blevet et stærkt brand for DR, Emmyer for bedste internationale drama og herhjemme er man begyndt at tage for serie siden 2002.1 Senest har Forbrydelsen I givet, at alle serier er succeser, som samler (2007) taget både de britiske tv-anmeldere omkring halvanden million danskere foran og seere med storm, mens den amerikan skærmen og får internationale priser med 180 ske remake, The Killing (2011 -), har fundet på vejen. af Eva Novrup Redvall Succesen er på ingen måde en selvfølge den kreative proces, der opstår i samarbej for en public service-kanal. Det kan man det mellem instruktører og manuskript bl.a. se af de diskussioner om tv-drama, forfattere (Redvall 2010a). Blandt mine man har i Norge og Sverige, hvor de dan konklusioner var, at selv om manuskript- ske serier ofte fremhæves, og hvor DRs skrivning som fag og profession i dag ny produktionsmodeller karakteriseres som der stor anerkendelse, er det generelt in ‘best practice (Bondebjerg og Redvall struktørerne, man ser som initiativtagerne 2011: 99-104). -

Introduction to the 2018 Convocation for Restoration

Introduction to the 2018 Convocation for Restoration and Renewal of the Undivided Church: Through a renewed Catholicity – Dublin, Ireland – March 2018 The Polish National Catholic Church and the Declaration and Union of Scranton by the Very Rev. Robert M. Nemkovich Jr. The Polish National Catholic Church promulgated the Declaration of Scranton in 2008 to preserve true and genuine Old Catholicism and allow for a Union of Churches that would be a beacon for and home to people of all nations who aspire to union with the pristine faith of the undivided Church. The Declaration of Scranton “is modeled heavily on the 1889 Declaration of Utrecht of the Old Catholic Churches. This is true not only in its content, but also in the reason for its coming to fruition.”1 The Polish National Catholic Church to this day holds the Declaration of Utrecht as a normative document of faith. To understand the origins of the Declaration of Utrecht we must look back not only to the origin of the Old Catholic Movement as a response to the First Vatican Council but to the very see of Utrecht itself. “The bishopric of Utrecht, which until the sixteenth century had been the only bishopric in what is now Dutch territory, was founded by St. Willibrord, an English missionary bishop from Yorkshire.”2 Willibrord was consecrated in Rome by Pope Sergius I in 696, given the pallium of an archbishop and given the see of Utrecht by Pepin, the Mayor of the Palace of the Merovingian dynasty. Utrecht became under Willibrord the ecclesiastical capital of the Northern Netherlands. -

Jul19nn:Layout 1.Qxd

Niftynotes news & information from the Diocese www.southwell.anglican.org JULY 2019 Compiled by Nicola Mellors email: [email protected] Eighteen were ordained this summer former anaesthetist and a when they served together in the long-serving lay minister Lee Abbey Community in Devon. Aworking with children They then lived and worked in and families were among the ten Bristol and Richard trained for deacon candidates for this year’s Ordination at Trinity College, ordinations. Bristol. He is serving his title with The Revd Dave Gough in The Bishop of Southwell & the Worksop St Anne Benefice & Nottingham, the Rt Revd Paul Norton Cuckney Benefice. Williams ordained nine deacons on Sunday 30th June at 11am and SIMON JONES. Simon spent seven priests on Saturday 29th almost 30 years working in the June in Southwell Minster. technology sector for Photo: Jack Bull organisations such as HSBC, Deacon candidate Jamie Franklin Matt Roberts in the Woodthorpe Cable & Wireless, Microsoft. and priest candidate Michael Benefice. Simon trained for ministry part- Vyse were ordained by the The time at the Queen’s Foundation, Right Reverend Glyn Webster at MIKE FORSYTH. Mike Birmingham. He is married to St George’s Church in The trained as a chef before joining Helen who works as the Meadows, Nottingham, on the RAF as a Logistics Officer, Continued on page 2 Sunday 30th June. serving in the UK, Falkland In this month’s issue: Islands and Afghanistan. Mike is Priest Candidates 2019 married to Rachel and they have two daughters, Evie (3) and 2 New in brief JACK BULL. -

The Two Folk Churches in Finland

The Two Folk Churches in Finland The 12th Finnish Lutheran-Orthodox Theological Discussions 2014 Publications of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland 29 The Church and Action The Two Folk Churches in Finland The 12th Finnish Lutheran-Orthodox Theological Discussions 2014 Publications of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland 29 The Church and Action National Church Council Department for International Relations Helsinki 2015 The Two Folk Churches in Finland The 12th Finnish Lutheran-Orthodox Theological Discussions 2014 © National Church Council Department for International Relations Publications of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland 29 The Church and Action Documents exchanged between the churches (consultations and reports) Tasknumber: 2015-00362 Editor: Tomi Karttunen Translator: Rupert Moreton Book design: Unigrafia/ Hanna Sario Layout: Emma Martikainen Photos: Kirkon kuvapankki/Arto Takala, Heikki Jääskeläinen, Emma Martikainen ISBN 978-951-789-506-4 (paperback) ISBN 978-951-789-507-1 (PDF) ISSN 2341-9393 (Print) ISSN 2341-9407 (Online) Unigrafia Helsinki 2015 CONTENTS Foreword ..................................................................................................... 5 THE TWELFTH THEOLOGICAL DISCUSSIONS BETWEEN THE EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN CHURCH OF FINLAND AND THE ORTHODOX CHURCH OF FINLAND, 2014 Communiqué. ............................................................................................. 9 A Theological and Practical Overview of the Folk Church, opening speech Bishop Arseni ............................................................................................ -

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2021

PORVOO PRAYER DIARY 2021 The Porvoo Declaration commits the churches which have signed it ‘to share a common life’ and ‘to pray for and with one another’. An important way of doing this is to pray through the year for the Porvoo churches and their Dioceses. The Prayer Diary is a list of Porvoo Communion Dioceses or churches covering each Sunday of the year, mindful of the many calls upon compilers of intercessions, and the environmental and production costs of printing a more elaborate list. Those using the calendar are invited to choose one day each week on which they will pray for the Porvoo churches. It is hoped that individuals and parishes, cathedrals and religious orders will make use of the Calendar in their own cycle of prayer week by week. In addition to the churches which have approved the Porvoo Declaration, we continue to pray for churches with observer status. Observers attend all the meetings held under the Agreement. The Calendar may be freely copied or emailed for wider circulation. The Prayer Diary is updated once a year. For corrections and updates, please contact Ecumenical Officer, Maria Bergstrand, Ms., Stockholm Diocese, Church of Sweden, E-mail: [email protected] JANUARY 3/1 Church of England: Diocese of London, Bishop Sarah Mullally, Bishop Graham Tomlin, Bishop Pete Broadbent, Bishop Rob Wickham, Bishop Jonathan Baker, Bishop Ric Thorpe, Bishop Joanne Grenfell. Church of Norway: Diocese of Nidaros/ New see and Trondheim, Presiding Bishop Olav Fykse Tveit, Bishop Herborg Oline Finnset 10/1 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Oulu, Bishop Jukka Keskitalo Church of Norway: Diocese of Sør-Hålogaland (Bodø), Bishop Ann-Helen Fjeldstad Jusnes Church of England: Diocese of Coventry, Bishop Christopher Cocksworth, Bishop John Stroyan. -

Christ- Katholischer Kirche" in Deutschland

Erstmals Bischofsweihe bei "Christ- Katholischer Kirche" in Deutschland Sie haben sich von den Altkatholiken abgespalten, weil sie gegen die Ordination von Frauen und die Segnung gleichgeschlechtlicher Partnerschaften sind: Jetzt bekommt die "Christ-Katholische Kirche" ihre ersten Bischöfe. Die 2012 in München gegründete "Christ-Katholische Kirche" (CKK) in Deutschland erhält erstmals einen Bischof und einen Weihbischof. Die Weihe, die durch Bischöfe "befreundeter Kirchen" vorgenommen wird, findet am 19. Mai in der Schlossparkhalle im unterfränkischen Urspringen statt. Das teilte die Kirche im oberbayerischen Einsbach mit. Mit diesem Schritt werde die seit sieben Jahren laufende Aufbauphase abgeschlossen. Zum Bischof geweiht wird der bisherige Generalvikar Klaus Mass. Er wurde 1970 in Verden an der Aller geboren und trat nach dem Abitur in den Karmeliterorden ein. Es folgte ein Studium der katholischen Theologie in Würzburg und Rom sowie später auch der altkatholischen Theologie in Bonn. Nach seiner Priesterweihe 2000 war er für die Priesterausbildung der unbeschuhten Karmeliten in Deutschland zuständig. Aufgrund seiner Eheschließung wechselte Mass in die altkatholische Kirche. 2012 wurde der Vater zweier Kinder Generalvikar der neuen CKK. Als Weihbischof ist Thomas Doell vorgesehen. Der Sohn eines Landwirts aus Unterfranken studierte ebenfalls Theologie in Würzburg und trat dann die altkatholische Kirche ein. Er ist verheiratet und Vater zweier erwachsener Kinder. Starke Impulse für Mission und Gemeindeaufbau habe er durch den US- Amerikaner Robert H. Schuller (Hour of Power) erhalten, heißt es. Mass und Doell seien von ersten Synode der Kirche, die im November 2018 in München tagte, in die jeweiligen Ämter gewählt worden. Die CKK lehnt die 1996 bei den Altkatholiken eingeführte Ordination von Frauen zum Priesteramt sowie die seit einigen Jahren praktizierte Segnung von gleichgeschlechtlichen Partnerschaften ab. -

Creating Holy People and Places on the Periphery

Creating Holy People and People Places Holy on theCreating Periphery Creating Holy People and Places on the Periphery A Study of the Emergence of Cults of Native Saints in the Ecclesiastical Provinces of Lund and Uppsala from the Eleventh to the Thirteenth Centuries During the medieval period, the introduction of a new belief system brought profound societal change to Scandinavia. One of the elements of this new religion was the cult of saints. This thesis examines the emergence of new cults of saints native to the region that became the ecclesiastical provinces of Lund and Uppsala in the twelfth century. The study examines theearliest, extant evidence for these cults, in particular that found in liturgical fragments. By analyzing and then comparing the relationship that each native saint’s cult had to the Christianization, the study reveals a mutually beneficial bond between these cults and a newly emerging Christian society. Sara E. EllisSara Nilsson Sara E. Ellis Nilsson Dissertation from the Department of Historical Studies ISBN 978-91-628-9274-6 Creating Holy People and Places on the Periphery Dissertation from the Department of Historical Studies Creating Holy People and Places on the Periphery A Study of the Emergence of Cults of Native Saints in the Ecclesiastical Provinces of Lund and Uppsala from the Eleventh to the Th irteenth Centuries Sara E. Ellis Nilsson med en svensk sammanfattning Avhandling för fi losofi e doktorsexamen i historia Göteborgs universitet, den 20 februari 2015 Institutionen för historiska studier (Department of Historical Studies) ISBN: 978-91-628-9274-6 ISBN: 978-91-628-9275-3 (e-publikation) Distribution: Sara Ellis Nilsson, [email protected] © Sara E. -

2016-04-15 Synod Address

Diocese of the Holy Cross SYNOD ADDRESS by the Rt. Rev. Paul C. Hewett, SSC Friday, April 15, 2016 at the Cathedral Church of the Epiphany, Columbia, SC May we take this time to thank the ladies at Epiphany, our ACW, for all their help in setting up this holy Synod, and to thank everyone who has taken the time to come. Today we welcome Carolyn Eigel from Holy Trinity Anglican Catholic Church in Greenville, South Carolina. She is here to commend Church School curricula she has been working on, displayed downstairs. It is also a pleasure to welcome St. Francis of Assisi, Spartanburg and their Rector, Fr. Nicholas Voyadgis, and the Nazareth House Apostolate in Taylorsville, Kentucky, with a warm welcome to Fr. Seraphim and Vicki, and to the new Rector of St. Mary the Virgin, Liverpool, New York. Fr. Richard Cumming. Bishop Timothy Farmer and Patsi send their warmest greetings and wish they could be with us. He is higher on the list for a kidney transplant, and we keep him in our prayers for recovery. On Sunday, May 8, we are planning an Evensong at Christ Church, Southern Pines, to install Father John Sharpe as a Canon of the Diocese. On Saturday, May 28, Deacon Geordy Geddings will be ordained to the Priesthood to serve at St. Bede’s, Birmingham. Grace be unto you and peace, from God our Father, and from the Lord, Jesus Christ. Next year, in September of 2017, we celebrate the 40th anniversary of the 1977 Affirmation of St. Louis. The Denver Consecrations came in January of 1978.