The Novel Cassard Le Berbère, Published in 1921 by Robert Randau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colony and Empire, Colonialism and Imperialism: a Meaningful Distinction?

Comparative Studies in Society and History 2021;63(2):280–309. 0010-4175/21 © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Society for the Comparative Study of Society and History doi:10.1017/S0010417521000050 Colony and Empire, Colonialism and Imperialism: A Meaningful Distinction? KRISHAN KUMAR University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA It is a mistaken notion that planting of colonies and extending of Empire are necessarily one and the same thing. ———Major John Cartwright, Ten Letters to the Public Advertiser, 20 March–14 April 1774 (in Koebner 1961: 200). There are two ways to conquer a country; the first is to subordinate the inhabitants and govern them directly or indirectly.… The second is to replace the former inhabitants with the conquering race. ———Alexis de Tocqueville (2001[1841]: 61). One can instinctively think of neo-colonialism but there is no such thing as neo-settler colonialism. ———Lorenzo Veracini (2010: 100). WHAT’ S IN A NAME? It is rare in popular usage to distinguish between imperialism and colonialism. They are treated for most intents and purposes as synonyms. The same is true of many scholarly accounts, which move freely between imperialism and colonialism without apparently feeling any discomfort or need to explain themselves. So, for instance, Dane Kennedy defines colonialism as “the imposition by foreign power of direct rule over another people” (2016: 1), which for most people would do very well as a definition of empire, or imperialism. Moreover, he comments that “decolonization did not necessarily Acknowledgments: This paper is a much-revised version of a presentation given many years ago at a seminar on empires organized by Patricia Crone, at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton. -

Is There Tunisian Literature? Emergent Writing and Fractal Proliferation of Minor Voices

COLLOQUIA HUMANISTICA Faculty of “Artes Liberales” UniversityEwa Łukaszyk of Warsaw Is There Tunisian Literature? Emergent Writing and Fractal Proliferation of Minor Voices 1. or the last thirty years or so, “minor” has been one of the key terms Fin the literary studies. Its special meaning is due, in first instance, to Gilles Deleuze (1975), who put the quality of being minor as a condition of questioning, innovation and thus creativity. Also Harold Bloom (1973), with his complex vision of the literary process seen as an eternal fight of a minor poet against his great predecessors, contributed to this consideration for minority, regarded as the golden gate leading to true originality in literature. In this double limelight, being minor is fundamentally nothing else than becoming major. Nonetheless, it remains current in the literary studies to use the term “minor” without explicit reference to these creative and innovative dynamics. Such terms as “minor poet” or “minor literature” may also refer to a marginal reality, of secondary importance and lesser value. The usage of this term presupposes a comparison and explicit or implicit reference to such terms as “centre”, “dominant symbolic system” and finally, a great or “major” literature and its language. The minor may or may not struggle to displace that centre and to invert that hierarchy in order to become a new major. It may also happen that minor literatures and minor writers accept pacifically their peripheral position, contenting themselves with filling the space on the margin without engaging in the Bloomian agon or wrestling for influence and greatness. The usage of the term “minor literature” presupposes a comparative, globalizing vision. -

Domestic Colonies and Colonialism Vs Imperialism in Western Political Thought and Practise

Domestic Colonies and Colonialism vs Imperialism in Western Political Thought and Practise Over the last thirty years, there has been a rapidly expanding literature on colonialism and imperialism in the canon of modern western political thought including research done by James Tully, Glen Coulthard, David Armitage, Karuna Mantena, Duncan Bell, Jennifer Pitts, Inder Marwah, Uday Mehta and myself. In various ways, it has been argued the defense of colonization and/or imperialism is embedded within and instrumental to key modern western, particularly liberal, political theories. In this paper, I provide a new way to approach this question based on a largely overlooked historical reality - ‘domestic’ colonies. Using a domestic lens to re-examine colonialism, I demonstrate it is not only possible but necessary to distinguish colonialism from imperialism. While it is popular to see them as indistinguishable in most post-colonial scholarship, I will argue the existence of domestic colonies and their justifications require us to rethink not only the scope and meaning of colonies and colonialism but how they differ from empires and imperialism. Domestic colonies (proposed and/or created from the middle of the 19th century to the start of the 20th century) were rural entities inside the borders of one’s own state (as opposed to overseas) within which certain kinds of fellow citizens (as opposed to foreigners) were segregated and engaged in agrarian labour to ‘improve’ them and the ‘uncultivated’ land upon which they laboured. Three kinds of domestic colonies were proposed based upon the population within them: labour or home colonies for the ‘idle poor’ (vagrants, unemployed, beggars), farm 1 colonies for the ‘irrational’ (mentally ill, disabled, epileptic) and utopian colonies for political, religious and/or racial minorities. -

The Translation of an Exchange Between Taha Husayn and Mahmud Al-Mas`Adi Regarding the Latter's Play Al-Sudd (The Dam)

The Translation of an Exchange Between Taha Husayn and Mahmud al-Mas`adi Regarding the Latter's Play al-Sudd (The Dam) Mohamed-Salah Omri (Comparative Literature) May 1995 (Paper presented in fulfillment of the 3rd Comprehensive Examination) Reading Committee: Dr. Peter Heath, Chair Dr. William Matheson Dr. Randolph Pope A. Introduction 1.The Writers Taha Husayn (1889-1973) was at the peak of a prolific career in writing and public service in Egypt when he reviewed al-Sudd (The Dam) by the Tunisian writer Mahmud al- Mas`adi (1911-) in 1957.1 At the time, Husayn was perhaps the most influential Arab intellectual with world fame that brought him a nomination for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1949.2 His voluminous work includes novels and short stories, critical studies and translations from ancient Greek and modern French literatures, and numerous contributions to journals and newspapers. His three-volume autobiography, al-Ayyam, has enjoyed both wide popular appeal and intensive critical attention. Husayn played a critical role in the secularization of Egypt and the establishment of a new type of scholarship. His daring views on Egyptian culture voiced in his book Mustaqbal al-Thaqafa fi Masr (The Future of Culture in Egypt) had raised considerable debate. His study Fi al-shi`r al-Jahili (On Pre-Islamic Poetry) in which he casts doubt on the authenticity of pre-Islamic poetry and claims that some Koranic stories are myths is a landmark in scholarship on the subject. During this century, the author had moved from being a "bitterly controversial figure" to "virtual secular sainthood" to the position of "an Egyptian classic" (Malti-Douglas, 9-10). -

The Dynamics of Inclusion and Exclusion of Settler Colonialism: the Case of Palestine

NEAR EAST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS PROGRAM WHO IS ELIGIBLE TO EXIST? THE DYNAMICS OF INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION OF SETTLER COLONIALISM: THE CASE OF PALESTINE WALEED SALEM PhD THESIS NICOSIA 2019 WHO IS ELIGIBLE TO EXIST? THE DYNAMICS OF INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION OF SETTLER COLONIALISM: THE CASE OF PALESTINE WALEED SALEM NEAREAST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS PROGRAM PhD THESIS THESIS SUPERVISOR ASSOC. PROF. DR. UMUT KOLDAŞ NICOSIA 2019 ACCEPTANCE/APPROVAL We as the jury members certify that the PhD Thesis ‘Who is Eligible to Exist? The Dynamics of Inclusion and Exclusion of Settler Colonialism: The Case of Palestine’prepared by PhD Student Waleed Hasan Salem, defended on 26/4/2019 4 has been found satisfactory for the award of degree of Phd JURY MEMBERS ......................................................... Assoc. Prof. Dr. Umut Koldaş (Supervisor) Near East University Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Department of International Relations ......................................................... Assoc. Prof.Dr.Sait Ak şit(Head of Jury) Near East University Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Department of International Relations ......................................................... Assoc. Prof.Dr.Nur Köprülü Near East University Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Department of Political Science ......................................................... Assoc. Prof.Dr.Ali Dayıoğlu European University of Lefke -

Cover Pages and Abstract May 2014

The Contentious Classroom: Education in Postcolonial Literature from Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia Erin Twohig Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Erin Twohig All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Contentious Classroom: Education in Postcolonial Literature from Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia Erin Twohig ! My dissertation examines literary portraits of education in French- and Arabic-language literature from the Maghreb. The texts that I study recount their protagonists’ experience, as students or teachers, in the school system following independence in Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia. I focus, in particular, on debates relating to the “Arabization” of education. Arabizing education in the Maghreb was considered a fundamental act of decolonization, yet its promotion of a single national language provoked much criticism. I examine how authors use literary depictions of the classroom to treat critical topics surrounding language policy, national identity projects, the legacy of the colonial past, and the future of the education system. The chapters of this work explore four critical issues in discussions of education: the relationship between “colonial” and “postcolonial” education systems, the place of Amazigh (Berber) minorities in an Arabized education system, the effect of education on gender dynamics, and the “economics of education” which exclude many students from social mobility. This work examines thirteen literary texts, seven written in French and six in Arabic: ‘Abd al-Ghani Abu al-‘Azm’s Al ḍarīḥ and Al ḍarīḥ al akhar, Leila Abouzeid’s Rujūʻ ilā al-ṭufūlah and Al-Faṣl al-akhīr, Wahmed Ben Younes’s Yemma, Karima Berger’s L’enfant des deux mondes, Maissa Bey’s Bleu blanc vert, Wahiba Khiari’s Nos silences, Fouad Laroui’s “L’Etrange affaire du cahier bounni,” Mohamed Nedali’s Grâce à Jean de la Fontaine!, Brick Oussaïd’s Les coquelicots de l’oriental, Habib Selmi’s Jabal al-‘anz, and Zohr Wanissi’s Min Yawmīyāt Mudarrisah Ḥurrah. -

Land of Abundance: a History of Settler Colonialism in Southern California

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 6-2020 LAND OF ABUNDANCE: A HISTORY OF SETTLER COLONIALISM IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Benjamin Shultz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, Latin American History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Shultz, Benjamin, "LAND OF ABUNDANCE: A HISTORY OF SETTLER COLONIALISM IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA" (2020). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 985. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/985 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LAND OF ABUNDANCE: A HISTORY OF SETTLER COLONIALISM IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Social Sciences and Globalization by Benjamin O Shultz June 2020 LAND OF ABUNDANCE: A HISTORY OF SETTLER COLONIALISM IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Benjamin O Shultz June 2020 Approved by: Thomas Long, Committee Chair, History Teresa Velasquez, Committee Member, Anthropology Michal Kohout, Committee Member, Geography © 2020 Benjamin O Shultz ABSTRACT The historical narrative produced by settler colonialism has significantly impacted relationships among individuals, groups, and institutions. This thesis focuses on the enduring narrative of settler colonialism and its connection to American Civilization. -

Guide Publications De Beït Al-Hikma

Guide publications de Beït al-Hikma Tunisian Academy of Sciences, Letters and Arts, Beït al-Hikma 1 Guide to Publications of Beit al-Hikma / Tunisian Academy of Sciences, Letters and Arts Beit al-Hikma: 2010 (Tunis: SOTEP graphic printing) 268 p. 21 cm - Hardcover. ISBN: 978-9973-49-113-8 Books available at the Academy, may also be purchased online and in several bookstores. It was drawn from 2000 copies of this book in its first edition © All rights reserved the Tunisian Academy of Sciences, Literature and Art - Beit al-Hikma 2 Tunisian Academy of Sciences, Letters and Arts, Beït al-Hikma Established in 1983, the Beit Al-Hikma Foundation became in 1992 in conformity with the 116-92 act issued on 20 November 1992- “a public enterprise with industrial and commercial attributes, granted with civilian status and financially independent” and called« Tunisian Academy of Sciences, Letters and Arts, Beït Al-Hikma ». Historical background The present-day seat of the Tunisian Academy is symbolic on more than one account. During the Husseinite era, it was called “Zarrouk Palace” because it was founded by the General Ahmed Zarrouk whose name was closely associated with the ruthless crushing of the Ali Ben Ghedhahem revolt in 1864, in the Sahel and Aradh regions. From 1943 to 1957, this Palace was the official residence of Mohammed Lamine, the last Bey of Tunisia. It was in that prestigious architectural building that a reception was given for Jules Ferry, who was to impose the French protectorate on the Regency of Tunis. It was also in that same building that a major event in the history of modern Tunisia took place : the solemn proclamation, by the French President Pierre Mendès France, of Tunisia‟s home rule After independence, the Palace became the property of the state. -

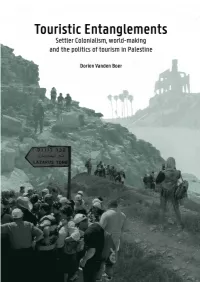

Touristic Entanglements

TOURISTIC ENTANGLEMENTS ii TOURISTIC ENTANGLEMENTS Settler colonialism, world-making and the politics of tourism in Palestine Dorien Vanden Boer Dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirement of the degree of Doctor in the Political and Social Sciences, option Political Sciences Ghent University July 2020 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Christopher Parker iv CONTENTS Summary .......................................................................................................... v List of figures.................................................................................................. vii List of Acronyms ............................................................................................... ix Acknowledgements........................................................................................... xi Preface ........................................................................................................... xv Part I: Routes into settler colonial fantasies ............................................. 1 Introduction: Making sense of tourism in Palestine ................................. 3 1.1. Setting the scene: a cable car for Jerusalem ................................... 3 1.2. Questions, concepts and approach ................................................ 10 1.2.1. Entanglements of tourism ..................................................... 10 1.2.2. Situating Critical Tourism Studies and tourism as a colonial practice ................................................................................. 13 1.2.3. -

Understanding the Poem of the Burdah in Sufi Commentaries

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Archived Theses and Dissertations 6-1-2008 Understanding the poem of the Burdah in Sufi commentaries Rose Aslan Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/retro_etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Aslan, R. (2008).Understanding the poem of the Burdah in Sufi commentaries [Thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/retro_etds/2383 MLA Citation Aslan, Rose. Understanding the poem of the Burdah in Sufi commentaries. 2008. American University in Cairo, Thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/retro_etds/2383 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Archived Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American University in Cairo UNDERSTANDING THE POEM OF THE BURDAH IN SUFI COMMENTARIES A Thesis Submitted to The Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts by Rose Aslan (under the supervision of Dr. Abdel Rahman Salem) June 2008 The American University in Cairo UNDERSTANDING THE POEM OF THE BURDAH IN SUFI COMMENTARIES A Thesis Submitted by Rose Aslan To the Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations June 2008 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for The degree of Masters of Arts Has been approved by Dr. Abdel Rahman Salem Thesis -

The Settler-Colonial Mythology Of

“GO UP (AGAIN) TO JERUSALEM IN JUDAH”: THE SETTLER-COLONIAL MYTHOLOGY OF “RETURN” AND “RESTORATION” IN EZRA 1–6 by Dustin Michael Naegle Bachelor of Science, 2004 Utah State University Logan, UT Master of Theological Studies, 2007 Brite Divinity School Fort Worth, TX Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Brite Divinity School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Theology in Biblical Interpretation Fort Worth, TX April 2017 “GO UP (AGAIN) TO JERUSALEM IN JUDAH”: THE SETTLER-COLONIAL MYTHOLOGY OF “RETURN” AND “RESTORATION” IN EZRA 1–6 APPROVED BY THESIS COMMITTEE Claudia V. Camp Thesis Director David M. Gunn Reader Jeffrey Williams Associate Dean for Academic Affairs Joretta Marshall Dean For Dad (1958–1985) iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The list of people to whom I am indebted for the completion of this project exceeds far beyond what space allows. I am particularly thankful to my director and mentor Claudia V. Camp, who taught me what good scholarship is by challenging me intellectually and fostering my research interests. I am particularly thankful for the countless hours she devoted to reviewing and commenting on my work. Her guidance and support has profoundly influenced me as a scholar and as a human being. I am honored to have been her student. I am also thankful to David M. Gunn for his willingness to serve as a reader for this project. His insight and support proved to be invaluable. I also wish to thank Lorenzo Veracini, Patricia Lorcin, and Tamara Eskenazi who all provided helpful feedback. I would also like to thank the many teachers who helped shape my understanding of the world, particularly Warren Carter, Toni Craven, Steve Sprinkle, and Elaine Robinson. -

Settler Colonialism As Structure

SREXXX10.1177/2332649214560440Sociology of Race and EthnicityGlenn 560440research-article2014 Current (and Future) Theoretical Debates in Sociology of Race and Ethnicity Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 2015, Vol. 1(1) 54 –74 Settler Colonialism as © American Sociological Association 2014 DOI: 10.1177/2332649214560440 Structure: A Framework for sre.sagepub.com Comparative Studies of U.S. Race and Gender Formation Evelyn Nakano Glenn1 Abstract Understanding settler colonialism as an ongoing structure rather than a past historical event serves as the basis for an historically grounded and inclusive analysis of U.S. race and gender formation. The settler goal of seizing and establishing property rights over land and resources required the removal of indigenes, which was accomplished by various forms of direct and indirect violence, including militarized genocide. Settlers sought to control space, resources, and people not only by occupying land but also by establishing an exclusionary private property regime and coercive labor systems, including chattel slavery to work the land, extract resources, and build infrastructure. I examine the various ways in which the development of a white settler U.S. state and political economy shaped the race and gender formation of whites, Native Americans, African Americans, Mexican Americans, and Chinese Americans. Keywords settler colonialism, decolonization, race, gender, genocide, white supremacy In this article I argue for the necessity of a settler to fight racial injustice. Equally, I wish to avoid colonialism framework for an historically grounded seeing racisms affecting various groups as com- and inclusive analysis of U.S. race and gender for- pletely separate and unrelated. Rather, I endeavor mation. A settler colonialism framework can to uncover some of the articulations among differ- encompass the specificities of racisms and sexisms ent racisms that would suggest more effective affecting different racialized groups—especially bases for cross-group alliances.