Settler Colonialism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colony and Empire, Colonialism and Imperialism: a Meaningful Distinction?

Comparative Studies in Society and History 2021;63(2):280–309. 0010-4175/21 © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Society for the Comparative Study of Society and History doi:10.1017/S0010417521000050 Colony and Empire, Colonialism and Imperialism: A Meaningful Distinction? KRISHAN KUMAR University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA It is a mistaken notion that planting of colonies and extending of Empire are necessarily one and the same thing. ———Major John Cartwright, Ten Letters to the Public Advertiser, 20 March–14 April 1774 (in Koebner 1961: 200). There are two ways to conquer a country; the first is to subordinate the inhabitants and govern them directly or indirectly.… The second is to replace the former inhabitants with the conquering race. ———Alexis de Tocqueville (2001[1841]: 61). One can instinctively think of neo-colonialism but there is no such thing as neo-settler colonialism. ———Lorenzo Veracini (2010: 100). WHAT’ S IN A NAME? It is rare in popular usage to distinguish between imperialism and colonialism. They are treated for most intents and purposes as synonyms. The same is true of many scholarly accounts, which move freely between imperialism and colonialism without apparently feeling any discomfort or need to explain themselves. So, for instance, Dane Kennedy defines colonialism as “the imposition by foreign power of direct rule over another people” (2016: 1), which for most people would do very well as a definition of empire, or imperialism. Moreover, he comments that “decolonization did not necessarily Acknowledgments: This paper is a much-revised version of a presentation given many years ago at a seminar on empires organized by Patricia Crone, at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton. -

Domestic Colonies and Colonialism Vs Imperialism in Western Political Thought and Practise

Domestic Colonies and Colonialism vs Imperialism in Western Political Thought and Practise Over the last thirty years, there has been a rapidly expanding literature on colonialism and imperialism in the canon of modern western political thought including research done by James Tully, Glen Coulthard, David Armitage, Karuna Mantena, Duncan Bell, Jennifer Pitts, Inder Marwah, Uday Mehta and myself. In various ways, it has been argued the defense of colonization and/or imperialism is embedded within and instrumental to key modern western, particularly liberal, political theories. In this paper, I provide a new way to approach this question based on a largely overlooked historical reality - ‘domestic’ colonies. Using a domestic lens to re-examine colonialism, I demonstrate it is not only possible but necessary to distinguish colonialism from imperialism. While it is popular to see them as indistinguishable in most post-colonial scholarship, I will argue the existence of domestic colonies and their justifications require us to rethink not only the scope and meaning of colonies and colonialism but how they differ from empires and imperialism. Domestic colonies (proposed and/or created from the middle of the 19th century to the start of the 20th century) were rural entities inside the borders of one’s own state (as opposed to overseas) within which certain kinds of fellow citizens (as opposed to foreigners) were segregated and engaged in agrarian labour to ‘improve’ them and the ‘uncultivated’ land upon which they laboured. Three kinds of domestic colonies were proposed based upon the population within them: labour or home colonies for the ‘idle poor’ (vagrants, unemployed, beggars), farm 1 colonies for the ‘irrational’ (mentally ill, disabled, epileptic) and utopian colonies for political, religious and/or racial minorities. -

Ali a Mazrui on the Invention of Africa and Postcolonial Predicaments1

‘My life is One Long Debate’: Ali A Mazrui on the Invention of Africa and Postcolonial Predicaments1 Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni2 Archie Mafeje Research Institute University of South Africa Introduction It is a great honour to have been invited by the Vice-Chancellor and Rector Professor Jonathan Jansen and the Centre for African Studies at the University of the Free State (UFS) to deliver this lecture in memory of Professor Ali A. Mazrui. I have chosen to speak on Ali A. Mazrui on the Invention of Africa and Postcolonial Predicaments because it is a theme closely connected to Mazrui’s academic and intellectual work and constitute an important part of my own research on power, knowledge and identity in Africa. Remembering Ali A Mazrui It is said that when the journalist and reporter for the Christian Science Monitor Arthur Unger challenged and questioned Mazrui on some of the issues raised in his televised series entitled The Africans: A Triple Heritage (1986), he smiled and responded this way: ‘Good, [...]. Many people disagree with me. My life is one long debate’ (Family Obituary of Ali Mazrui 2014). The logical question is how do we remember Professor Ali A Mazrui who died on Sunday 12 October 2014 and who understood his life to be ‘one long debate’? More importantly how do we reflect fairly on Mazrui’s academic and intellectual life without falling into the traps of what the South Sudanese scholar Dustan M. Wai (1984) coined as Mazruiphilia (hagiographical pro-Mazruism) and Mazruiphobia (aggressive anti-Mazruism)? How do we pay tribute -

The Dynamics of Inclusion and Exclusion of Settler Colonialism: the Case of Palestine

NEAR EAST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS PROGRAM WHO IS ELIGIBLE TO EXIST? THE DYNAMICS OF INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION OF SETTLER COLONIALISM: THE CASE OF PALESTINE WALEED SALEM PhD THESIS NICOSIA 2019 WHO IS ELIGIBLE TO EXIST? THE DYNAMICS OF INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION OF SETTLER COLONIALISM: THE CASE OF PALESTINE WALEED SALEM NEAREAST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS PROGRAM PhD THESIS THESIS SUPERVISOR ASSOC. PROF. DR. UMUT KOLDAŞ NICOSIA 2019 ACCEPTANCE/APPROVAL We as the jury members certify that the PhD Thesis ‘Who is Eligible to Exist? The Dynamics of Inclusion and Exclusion of Settler Colonialism: The Case of Palestine’prepared by PhD Student Waleed Hasan Salem, defended on 26/4/2019 4 has been found satisfactory for the award of degree of Phd JURY MEMBERS ......................................................... Assoc. Prof. Dr. Umut Koldaş (Supervisor) Near East University Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Department of International Relations ......................................................... Assoc. Prof.Dr.Sait Ak şit(Head of Jury) Near East University Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Department of International Relations ......................................................... Assoc. Prof.Dr.Nur Köprülü Near East University Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Department of Political Science ......................................................... Assoc. Prof.Dr.Ali Dayıoğlu European University of Lefke -

Confronting Settler Colonialism in Food Movements

Running head: CONFRONTING SETTLER COLONIALISM IN FOOD MOVEMENTS Confronting Settler Colonialism in Food Movements By Michaela Bohunicky A thesis presented to Lakehead University in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Health Sciences With specialization in Social-Ecological Systems, Sustainability, and Health Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada, 2020 © Michaela Bohunicky 2020 CONFRONTING SETTLER COLONIALISM IN FOOD SYSTEMS Approval 2 CONFRONTING SETTLER COLONIALISM IN FOOD SYSTEMS Declaration of originality I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. 3 CONFRONTING SETTLER COLONIALISM IN FOOD SYSTEMS Abstract The dominant global capitalist food system is contributing significantly to social, political, ecological, and economic crises around the world. In response, food movements have emerged to challenge the legitimacy of corporate power, neoliberal trade policies, and the exploitation of people and natural resources. Despite important accomplishments, food movements have been criticized for reinforcing aspects of the dominant food system. This includes settler colonialism, a fundamental issue uniquely and intimately tied to food systems that has not received the attention it deserves in food movement scholarship or practice. While there is a small but growing body of literature that speaks to settler colonialism in contemporary -

Decolonization, Development, and Denial Natsu Taylor Saito

Florida A & M University Law Review Volume 6 Number 1 Social Justice, Development & Equality: Article 1 Comparative Perspectives on Modern Praxis Fall 2010 Decolonization, Development, and Denial Natsu Taylor Saito Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.law.famu.edu/famulawreview Recommended Citation Natsu T. Saito, Decolonization, Development, and Denial, 6 Fla. A&M U. L. Rev. (2010). Available at: http://commons.law.famu.edu/famulawreview/vol6/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ FAMU Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida A & M University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ FAMU Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DECOLONIZATION, DEVELOPMENT, AND DENIAL Natsu Taylor Saito* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................. 1 R 11. THE TRANSITION FROM DECOLONIZATION TO DEVELOPMENT ............................................. 6 R A. Inherently Contradictory:Decolonizing Under Colonial Rules ............................................ 8 R B. The Influence of InternationalFinancial Institutions . 12 R C. "Good Governance" and "FailedStates" ............... 17 R III. DEVELOPMENT AS A COLONIAL CONSTRUCT ................ 21 R A. "Guardianship"as a Justificationfor Colonial Appropriation.................................... 22 R B. Self-Determination and the League of Nation's Mandate System ................................. 25 R C. The Persistence of the Development Model ........... -

Land of Abundance: a History of Settler Colonialism in Southern California

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 6-2020 LAND OF ABUNDANCE: A HISTORY OF SETTLER COLONIALISM IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Benjamin Shultz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, Latin American History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Shultz, Benjamin, "LAND OF ABUNDANCE: A HISTORY OF SETTLER COLONIALISM IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA" (2020). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 985. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/985 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LAND OF ABUNDANCE: A HISTORY OF SETTLER COLONIALISM IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Social Sciences and Globalization by Benjamin O Shultz June 2020 LAND OF ABUNDANCE: A HISTORY OF SETTLER COLONIALISM IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Benjamin O Shultz June 2020 Approved by: Thomas Long, Committee Chair, History Teresa Velasquez, Committee Member, Anthropology Michal Kohout, Committee Member, Geography © 2020 Benjamin O Shultz ABSTRACT The historical narrative produced by settler colonialism has significantly impacted relationships among individuals, groups, and institutions. This thesis focuses on the enduring narrative of settler colonialism and its connection to American Civilization. -

Remapping the World: Vine Deloria, Jr. and the Ends of Settler Sovereignty

Remapping the World: Vine Deloria, Jr. and the Ends of Settler Sovereignty A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY David Myer Temin IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Joan Tronto October 2016 © David Temin 2016 i Acknowledgements Perhaps the strangest part of acknowledging others for their part in your dissertation is the knowledge that no thanks could possibly be enough. At Minnesota, I count myself lucky to have worked with professors and fellow graduate students alike who encouraged me to explore ideas, take intellectual risks, and keep an eye on the political stakes of any project I might pursue. That is why I could do a project like this one and still feel emboldened that I had something important and worthwhile to say. To begin, my advisor, Joan Tronto, deserves special thanks. Joan was supportive and generous at every turn, always assuring me that the project was coming together even when I barely could see ahead through the thicket to a clearing. Joan went above and beyond in reading countless drafts, always cheerfully commenting or commiserating and getting me to focus on power and responsibility in whatever debate I had found myself wading into. Joan is a model of intellectual charity and rigor, and I will be attempting to emulate her uncanny ability to cut through the morass of complicated debates for the rest of my academic life. Other committee members also provided crucial support: Nancy Luxon, too, read an endless supply of drafts and memos. She has taught me more about writing and crafting arguments than anyone in my academic career, which has benefited the shape of the dissertation in so many ways. -

The Novel Cassard Le Berbère, Published in 1921 by Robert Randau

History, Literature, and Settler Colonialism in North Africa Mohamed-Salah Omri he novel Cassard le Berbère, published in 1921 by Robert Randau T(1873–1950), a key fi gure in the Francophone culture of Algeria, tells the story of a settler named Cassard-colon who traces his ancestry to a pirate, Cassard-corsaire. The family of Cassard-corsaire settled in the mountains of Provence during the Islamic invasion of the region. Cassard-colon returns to North Africa and barricades himself in Borj Rais, formerly a Byzantine castle built on the remains of a Roman villa, which in turn stood atop a Punic necropolis. The invention and staging of a historical memory for the homecoming of Cassard-colon may be spectacular, but there is nothing fantastic about their implications. In fact, neither Cassard-colon’s ancestry nor his fortress, given Mediterra- nean cultural and historical contexts, is totally implausible.1 Randau’s An earlier version of this essay was presented at the Fourth Mediterranean Social and Political Research Meeting, Florence and Montecatini Terme, Italy, March 19–23, 2003; the meeting was organized by the Mediterranean Programme of the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute. I would like to thank the participants in the workshop “The Mediterranean: A Sea That Unites/A Sea That Divides” for their remarks, Florence Martin for commenting on earlier versions of the essay, and Nisrine Omri for her thoughtful editing. The essay is dedicated to Fatin from the occupied Palestinian West Bank, for her story and the story of her people run beneath and through this one. -

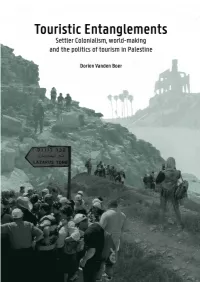

Touristic Entanglements

TOURISTIC ENTANGLEMENTS ii TOURISTIC ENTANGLEMENTS Settler colonialism, world-making and the politics of tourism in Palestine Dorien Vanden Boer Dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirement of the degree of Doctor in the Political and Social Sciences, option Political Sciences Ghent University July 2020 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Christopher Parker iv CONTENTS Summary .......................................................................................................... v List of figures.................................................................................................. vii List of Acronyms ............................................................................................... ix Acknowledgements........................................................................................... xi Preface ........................................................................................................... xv Part I: Routes into settler colonial fantasies ............................................. 1 Introduction: Making sense of tourism in Palestine ................................. 3 1.1. Setting the scene: a cable car for Jerusalem ................................... 3 1.2. Questions, concepts and approach ................................................ 10 1.2.1. Entanglements of tourism ..................................................... 10 1.2.2. Situating Critical Tourism Studies and tourism as a colonial practice ................................................................................. 13 1.2.3. -

THE EXPLOITATION of AFRICA and AFRICANS by the WESTERN WORLD SINCE 1500: a BIRD’S EYE VIEW 1 Sampie Terreblanche

THE EXPLOITATION OF AFRICA AND AFRICANS BY THE WESTERN WORLD SINCE 1500: A BIRD’S EYE VIEW 1 Sampie TerreblanChe STATEMENT The exploitation of Africa and Africans by the Western world since 1500, made an invaluable – and even an indispensable – contribution to the building of the economies of three continents (South America, North America and Europe), while products that embodied large quantities of cheap African slave labour, were used by Europe to seriously harm the economy of another continent (Asia). AFRICA AS A “BROKEN” CONTINENT The 500 years of European slavery and colonialism seriously harmed the African economy, damaged the African societal structures and undermined the psychological self-assurance of Africans. • Africa’s per capita income as a percentage of the per capita income of the West declined from 55% in 1500, to 22% in 1913 to 6% today. • Scale of Poverty: o 61% live on < $2 a day o 21% live on between $2 and $4 a day o 14% live on between $4 and $20 a day o 4% live on > $20 a day (Africa Progress Panel of the United Nations) 1 Paper read at the uBuntu Conference at the Law Faculty of the University of Pretoria, 2 – 4 August 2011. 1 AFRICAN SLAVERY • Muslim slave traders “exported” ± 8 million African slaves to southern Europe and to Asia Minor between 700 – 1400. Little is known about their contribution to the economy of the Mediterranean world. • Portugal got permission from the Pope to practice slavery in 1445 on condition that it should try to convert the slaves to Christianity. -

The Settler-Colonial Mythology Of

“GO UP (AGAIN) TO JERUSALEM IN JUDAH”: THE SETTLER-COLONIAL MYTHOLOGY OF “RETURN” AND “RESTORATION” IN EZRA 1–6 by Dustin Michael Naegle Bachelor of Science, 2004 Utah State University Logan, UT Master of Theological Studies, 2007 Brite Divinity School Fort Worth, TX Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Brite Divinity School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Theology in Biblical Interpretation Fort Worth, TX April 2017 “GO UP (AGAIN) TO JERUSALEM IN JUDAH”: THE SETTLER-COLONIAL MYTHOLOGY OF “RETURN” AND “RESTORATION” IN EZRA 1–6 APPROVED BY THESIS COMMITTEE Claudia V. Camp Thesis Director David M. Gunn Reader Jeffrey Williams Associate Dean for Academic Affairs Joretta Marshall Dean For Dad (1958–1985) iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The list of people to whom I am indebted for the completion of this project exceeds far beyond what space allows. I am particularly thankful to my director and mentor Claudia V. Camp, who taught me what good scholarship is by challenging me intellectually and fostering my research interests. I am particularly thankful for the countless hours she devoted to reviewing and commenting on my work. Her guidance and support has profoundly influenced me as a scholar and as a human being. I am honored to have been her student. I am also thankful to David M. Gunn for his willingness to serve as a reader for this project. His insight and support proved to be invaluable. I also wish to thank Lorenzo Veracini, Patricia Lorcin, and Tamara Eskenazi who all provided helpful feedback. I would also like to thank the many teachers who helped shape my understanding of the world, particularly Warren Carter, Toni Craven, Steve Sprinkle, and Elaine Robinson.