Page 1-3.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Myanmar-Thailand Corridor 6 the Myanmar-Malaysia Corridor 16 the Myanmar-Korea Corridor 22 Migration Corridors Without Labor Attachés 25

Online Appendixes Public Disclosure Authorized Labor Mobility As a Jobs Strategy for Myanmar STRENGTHENING ACTIVE LABOR MARKET POLICIES TO ENHANCE THE BENEFITS OF MOBILITY Public Disclosure Authorized Mauro Testaverde Harry Moroz Public Disclosure Authorized Puja Dutta Public Disclosure Authorized Contents Appendix 1 Labor Exchange Offices in Myanmar 1 Appendix 2 Forms used to collect information at Labor Exchange Offices 3 Appendix 3 Registering jobseekers and vacancies at Labor Exchange Offices 5 Appendix 4 The migration process in Myanmar 6 The Myanmar-Thailand corridor 6 The Myanmar-Malaysia corridor 16 The Myanmar-Korea corridor 22 Migration corridors without labor attachés 25 Appendix 5 Obtaining an Overseas Worker Identification Card (OWIC) 29 Appendix 6 Obtaining a passport 30 Cover Photo: Somrerk Witthayanant/ Shutterstock Appendix 1 Labor Exchange Offices in Myanmar State/Region Name State/Region Name Yangon No (1) LEO Tanintharyi Dawei Township Office Yangon No (2/3) LEO Tanintharyi Myeik Township Office Yangon No (3) LEO Tanintharyi Kawthoung Township Office Yangon No (4) LEO Magway Magwe Township Office Yangon No (5) LEO Magway Minbu District Office Yangon No (6/11/12) LEO Magway Pakokku District Office Yangon No (7) LEO Magway Chauk Township Office Yangon No (8/9) LEO Magway Yenangyaung Township Office Yangon No (10) LEO Magway Aunglan Township Office Yangon Mingalardon Township Office Sagaing Sagaing District Office Yangon Shwe Pyi Thar Township Sagaing Monywa District Office Yangon Hlaing Thar Yar Township Sagaing Shwe -

YANGON UNIVERSITY of ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT of ECONOMICS Ph.D PROGRAMME ECONOMIC VALUATION of ECOSYSTEM SERVICES in TAUNG THAMAN L

YANGON UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS Ph.D PROGRAMME ECONOMIC VALUATION OF ECOSYSTEM SERVICES IN TAUNG THAMAN LAKE YIN MYO OO JULY, 2020 i YANGON UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS Ph.D PROGRAMME ECONOMIC VALUATION OF ECOSYSTEM SERVICES IN TAUNG THAMAN LAKE YIN MYO OO 4- Ph.D (THU) BA-2 JULY, 2020 ii CERTIFICATION I hereby certify that the content of this dissertation is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. Information from sources is referenced with original comments and ideas of the writer herself. Yin Myo Oo 4- Ph.D (Thu) Ba-2 iii ABSTRACT This study aims to assign aggregate monetary values of the provisioning, regulating and cultural services on the Taung Thaman Lake in Amarapura Township, Mandalay. The objective is to investigate the factors influencing on willingness to pay (WTP) among villagers and visitors. The market value method is applied to evaluate the aggregate value of crop production in the Lake provisioning service. The contingent valuation method (CVM) is also applied to estimate the amount of money that villagers and visitors were willing to pay by using the binary logistic regression analysis. The Aggregate economic value of crop production from the Lake provisioning services is 49.53 million kyats per year in 2018-2019. The binary regression analysis result shows that the villager’s mean WTP for the water quality conservation is 1,128 Kyats/month/ households and the Aggregate WTP of the water quality conservation of the villagers of the Lake regulating service is 34.41 million Kyats/year/ households in 2018-2019. -

Discharge Historic Duty of Perpetuating Sovereignty

Established 1914 Volume XV, Number 264 12th Waning of Nadaw 1369 ME Saturday, 5 January, 2008 Discharge historic duty of perpetuating sovereignty In discharging the historic duty of safeguarding national independ- ence and perpetuating the sovereignty, all the national people are urged to make concerted efforts while enhancing the dynamic Union Spirit, patri- otism and nationalistic fervour, and developing the human resource. Senior General Than Shwe Chairman of the State Peace and Development Council Commander-in-Chief of Defence Services (From message sent on the occasion of the 53rd Anniversary Independence Day) Senior General Than Shwe, wife Daw Kyaing Kyaing host dinner to mark 60th Anniversary Independence Day NAY PYI TAW, 4 their wives welcomed Peace and Development try of Defence and wife, and wife, SPDC members officers of the Ministry of Jan — Chairman of the the Senior General. Council Vice-Senior Gen- Prime Minister General and their wives, the Com- Defence and their wives, State Peace and Devel- Also present at eral Maung Aye, SPDC Thein Sein and wife, Sec- mander-in-Chief (Navy), the Commander of Nay opment Council of the the dinner were Vice- member General Thura retary-1 Lt-Gen Thiha the Commander-in-Chief Pyi Taw Union of Myanmar Sen- Chairman of the State Shwe Mann of the Minis- Thura Tin Aung Myint Oo (Air) and senior military (See page 8) ior General Than Shwe and wife Daw Kyaing Kyaing hosted a dinner to mark the 60th Anni- versary Independence Day at the City Hall, here, this evening. At 6.30 pm, Senior General Than Shwe arrived at the City Hall where the dinner to mark the 60th Anniversary In- dependence Day was to be held. -

Environmental Problems: a Case Study of Amarapura Loom Weaving Area Nyun Linn Tun1 and Environmental Studies Students and Tin Moe Lwin2

1 Environmental Problems: A Case Study of Amarapura Loom Weaving Area Nyun Linn Tun1 and Environmental Studies Students and Tin Moe Lwin2 Abstract The loom weaving industry in Amarapura has been popular from the Konbaung dynasty to the present. Nowadays, although the advantages from the rapid growth of textile sector, consequently environmental problems concerning discharges of wastewater, emission air, noise and waste solid are actually problems to be solved for the industry. End -of- pipe technology has used as tools for sustainable development of industry activities during the past years. Here, the paper is presented the status, environmental problems of textile industry and environmental protect solutions have been carried out for textile industry in Amarapura. How to build a model of integrated approach combining both cleaner production and end-of-pile treatment for pollution prevention in the textile industry in Amarapura is still a question. To be a sustainable development for the loom weaving industry, it is required to organize a strong organization for controlling intellectual property right and to follow the instructions of waste management by the city development committee, dye limitations and also fair payment of labour. Key words: loom weaving industry, environmental problems, end-of-pipe technology Introduction Textile industry has attained great successes in recent years. It has some advantages and disadvantages. The advantages are increased production processes, products, and employment through expansion industry sectors as well as step by step to improve life condition of inhabitant. The disadvantages are serious environmental pollution and scarce resource causing turbulent development of the industry. The textile industry releases highly polluted and very alkali or acidity wastewater and the dyes often contain toxic substances such as chlorine, chromium, alkaline compounds, zinc and copper. -

A Chance to Fix in Time” Analysis of Freedom of Expression in Four Years Under the Current Government

Athan – Freedom of Expression Activist Organization “A Chance to Fix in Time” Analysis of Freedom of Expression in Four Years Under the Current Government 4 Research Report “A Chance to Fix in Time” Analysis of Freedom of Expression in Four Years Under the Current Government Research Report Athan – Freedom of Expression Activist Organization A Chance to Fix in Time: Analysis of Freedom of Expression in Four Years Under the Current Government Table of Contents Chapters Contents Pages Organisational Background d - Research Methodology 2 - Photo Copyright Chapter (1): Introduction 2 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Overall Analysis of Prosecutions within Four Years 4 Chapter (2): Freedom of Expression 8 2.1 Lawsuits under Telecommunications Law 9 2.2 Lawsuits under the Law Protecting the Privacy and Security 14 of Citizens 2.3 National Record and Archive Law 17 2.4 Lawsuits under Section 505(a), (b) and (c) of the Penal Code 18 2.5 Lawsuits under Section 500 of the Penal Code 23 2.6 Electronic Transactions Law Must Be Repealed 24 2.7 Lawsuits with Sedition Charge under Section 124(a) of the 25 Penal Code 2.8 Lawsuits under Section 295 of the Penal Code 26 2.9 Three Stats Where Free Expression Violated Most 27 Chapter (3): Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and Procession 30 3.1 More Restrictions Included in Drafted Amendment Bill 31 Chapter (4): Media Freedom 34 4.1 News Media Law Lacks of Protection for Media Freedom and 34 Journalistic Rights 4.2 The Tatmadaw’s Filing Lawsuits Against Irrawaddy and 36 Reuters News Agencies a Table of Contents A Chance to -

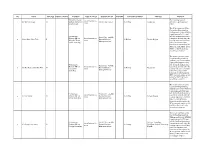

Warrant Lists English

No Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Minister of Social For encouraging civil Issued warrant to 1 Dr. Win Myat Aye M Welfare, Relief and Penal Code S:505-a In Hiding Naypyitaw servants to participate in arrest Resettlement CDM The 17 are members of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), a predominantly NLD and Pyihtaungsu self-declared parliamentary Penal Code - 505(B), Hluttaw MP for Issued warrant to committee formed after the 2 (Daw) Phyu Phyu Thin F Natural Disaster In Hiding Yangon Region Mingalar Taung arrest coup in response to military Management law Nyunt Township rule. The warrants were issued at each township the MPs represent, under article 505[b) of the Penal Code, according to sources. The 17 are members of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), a predominantly NLD and Pyihtaungsu self-declared parliamentary Penal Code - 505(B), Hluttaw MP for Issued warrant to committee formed after the 3 (U) Yee Mon (aka) U Tin Thit M Natural Disaster In Hiding Naypyitaw Potevathiri arrest coup in response to military Management law Township rule. The warrants were issued at each township the MPs represent, under article 505[b) of the Penal Code, according to sources. The 17 are members of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), a predominantly NLD and self-declared parliamentary Pyihtaungsu Penal Code - 505(B), Issued warrant to committee formed after the 4 (U) Tun Myint M Hluttaw MP for Natural Disaster In Hiding Yangon Region arrest coup in response to military Bahan Township Management law rule. -

No Store Name Region State/Province City District Address

No Store Name Region State/Province City District Address Contact No 1 SHOWROOM_O2 MAHARBANDOOLA (MM) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION WESTERN DISTRICT(DOWNTOWN) KYAUKTADA TOWNSHIP NO.212, PANSODAN ST. (MIDDLE BLOCK), KYAWKTADAR TSP 09 420162256 2 SHOWROOM_O2 BAGO (MM) LOWER MYANMAR BAGO REGION BAGO DISTRICT BAGO TOWNSHIP SHIN SAW PU QUARTER, BAGO TSP 09 967681616 3 SHOW ROOM _O2 _(SULE) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION WESTERN DISTRICT(DOWNTOWN) KYAUKTADA TOWNSHIP NO.118, SULAY PAGODA RD, KYAUKTADAR TSP 09 454147773 4 SHOWROOM_MOBILE KING ZEWANA (MM) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION EASTERN DISTRICT THINGANGYUN TOWNSHIP BLDG NO.38, ROOM B1, GROUND FL, LAYDAUNKAN ST, THINGANGYUN 09 955155994 5 SHOWROOM_M9_78ST(MM) UPPER MYANMAR MANDALAY REGION MANDALAY DISTRICT CHANAYETHAZAN TOWNSHIP NO.D3, 78 ST, BETWEEN 27 ST AND 28 ST, CHANAYETHARSAN TSP 09 977895028 6 SHOWROOM_M9 MAGWAY (MM) UPPER MYANMAR MAGWAY REGION MAGWAY DISTRICT MAGWAY TOWNSHIP MAGWAY TSP 09 977233181 7 SHOWROOM_M9_TAUNGYI (LANMADAW ROAD, TAUNGYIUPPER TSP) (MM) MYANMAR SHAN STATE TAUNGGYI DISTRICT TAUNGGYI TOWNSHIP LANMADAW ROAD, TAUNGYI TSP 09 977233182 8 SHOWROOM_M9 PYAY (MM) LOWER MYANMAR BAGO REGION PYAY DISTRICT PYAY TOWNSHIP LANMADAW ROAD, PYAY TSP 09 5376699 9 SHOWROOM_M9 MONYWA (MM), BOGYOKE ROAD, MONYWAUPPER TOWNSHIP MYANMAR SAGAING REGION MONYWA DISTRICT MONYWA TOWNSHIP BOGYOKE ROAD, MONYWA TSP. 09 977233179 10 SHOWROOM _O2_(BAK) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION EASTERN DISTRICT BOTATAUNG TOWNSHIP BO AUNG KYAW ROAD, LOWER 09 428189521 11 SHOWROOM_EXCELLENT (YAYKYAW) (MM) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON -

Myanmar Medical Council Executive Committee Meeting Held

CBM’S GUARANTEE EASES TENSIONS OF BANK CUSTOMERS PAGE 8 OPINION NATIONAL NATIONAL MoRAC Union Minister Deputy Minister for Investment and Foreign Economic Relations attends religious matters U Than Aung Kyaw meets investors from industrial zones PAGE 3 PAGE 3 Vol. VIII, No. 20, 13 th Waning of Tagu 1383 ME www.gnlm.com.mm Sunday, 9 May 2021 Republic of the Union of Myanmar Anti-Terrorism Central Committee Declaration of Terrorist Groups Notication No 2/2021 12th Waning of Tagu 1383 ME 8 May 2021 The Anti-Terrorism Central Committee has issued this order with the approval of the State Administration Council in exercising the Anti-Terrorism Law Section 6, sub-section (e), Section 72 and sub-section (b). 1. Unlawful Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw-CRPH and National Unity Government formed by CRPH constantly incited Civil Disobedience Move- ment-CDM participants to commit violent acts. Many riots occurred in many places of the country due to their incitements. They perpetrated bombing, arson, SEE PAGE 2 Myanmar Medical Council Executive Committee meeting held UNION Minister for Health and Minister and party met with the Sports Dr Thet Khaing Win at- officials of the COVID-19 Medical tended the Myanmar Medical Treatment Centre (Phaungyi) Council Executive Committee and discussed the acceptance of meeting held on 7 May. the COVID-19 patients and the At the meeting, the Union completion of new wards. Minister said the status of the The Union Minister ex- work to resume public health pressed words of thanks to the services throughout the country, Tatmadaw medical corps for the the assistance of the ministry to acceptance of the COVID-19 pa- those who want to return to work tients and said the purpose of and the action being taken to the his visit is to discuss to continue staff who do not return to work the medical work of COVID-19 in accordance with the rules and Medical Treatment Centre regulations. -

Republic of the Union of Myanmar Preparatory Survey on Distribution

Electricity Supply Enterprise Ministry of Electric Power Republic of the Union of Myanmar Republic of the Union of Myanmar Preparatory Survey on Distribution System Improvement Project in Main Cities Final Report July 2015 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Chubu Electric Power Co., Inc. 1R Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. JR 15-033 Table of contents Chapter 1 Background ........................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.2 Survey schedule .......................................................................................................................... 1-3 1.3 JICA survey team and counterpart .............................................................................................. 1-5 Chapter 2 Present Status ........................................................................................................ 2-1 2.1 Present status of the power distribution sector ........................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Movement of Corporatization and franchising ........................................................................... 2-6 2.3 Electricity Tariff .......................................................................................................................... 2-7 2.3.1 Number of Consumers ....................................................................................................... -

A Geographical Study on Seasonal Disesaes In

Title A Geographical Study on Seasonal Diseaes in Mandalay City Author Mya Mya Than Issue Date 2012 A GEOGRAPHICAL STUDY ON SEASONAL DISESAES IN MANDALAY CITY Mya Mya Than Abstract Mandalay City, an old capital lying in Central Myanmar, has favourable geographic conditions for the development of seasonal diseases. With a total population of 796,091 and a density of 19,253 persons per square mile, 0.65% to 0.77% of the population is recorded to have suffered, among the seasonal diseases, mainly from diarrhoea, Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever (DHF) and Acute Respiratory Infection (ARI) during the recent years. In this research, the researcher identifies the epidemic seasons from the geographical point of view: diarrhoea occurs mostly in the rainy season, DHF in the late rainy season, and ARI in the late rainy season to the early winter. As epidemic areas, diarrhoea prevails yearly or periodically in water-logged settlement areas and in wards of poor sanitation and human environment, DHF in those areas as well as in the slum areas, and ARI in places polluted by air indoor or in surrounding areas. Moreover, it is found that the occurrence of diarrhoea increases when temperature, rainfall, and humidity become higher. DHF cases also increase directly with the three climatic elements but the correlation is high with relative humidity and low with the other two. ARI cases increase reversely with temperature and rainfall, and directly with relative humidity. Finally, a conceived model showing the factors influencing upon seasonal diseases in Mandalay City is produced. Key Words: Seasonal Diseases DHF ARI Epidemic Season Introduction Epidemiologically disease distribution depends on time, place, and person (Alderson, 1983). -

Recent Fatality List for June 30, 2021 (English)

Date of Deceased Place of No. Name Sex Age Father's name Organization Home Adress Township States/Regions Remarks Incident Date Incidents In another incident, 32 year old Ko 75 Street, Na Pwar (aka) Ko Nyi Na Pwar (a.k.a Ko Ko Oo), died after 1 M 32 U Hla Ngwe 08-Feb-21 08-Feb-21 Civilian Mandalay between 37 and Mahaaungmye Mandalay Region Nyi Oo a car intentionally hit him at night in 38 Street Mandalay. On February 9, peaceful anti-coup protests in Naypyitaw were Hlaykhwintaung, suppressed using a water cannon, Lower rubber bullets and live ammunition Mya Thwate Thwate 2 F 19 unknown 09-Feb-21 19-Feb-21 Civilian NayPyi Taw Paunglaung Zeyathiri Naypyidaw resulting in four people being Khaing Hydro Power injured. Among them was Ma Mya Project Thawe Thawe Khaing, 21-years old, who, on 19 February later died from gunshot wounds to the head. On 15 February evening, 18-year old Myeik, Maung Nay Nay Win Htet was Tanintharyi 3 Nay Nay Win Htet M 18 unknown 15-Feb-21 15-Feb-21 Civilian Tanintharyi Toe Chal Ward Myeik beaten on his head to death while Region Region guarding a Warroad security in Myeik, Tanintharyi Region. In Mandalay, a shipyaroad raid turned violent on Saturday when Thet Naing Win @ Min Kannar Road, security forces opened fire on 4 M 37 U Maung San 20-Feb-21 20-Feb-21 Civilian Near 41 Street Mahaaungmye Mandalay Region Min Mandalay City demonstrators trying to stop the arrest of workers taking part in the growing anti-coup movement. -

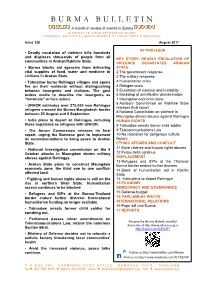

B U R M a B U L L E T

B U R M A B U L L E T I N A month-in-review of events in Burma A L T E R N A T I V E A S E A N N E T W O R K O N B U R M A campaigns, advocacy & capacity - building for human rights & democracy Issue 128 August 2017 IN THIS ISSUE • Deadly escalation of violence kills hundreds and displaces thousands of people from all KEY STORY: DEADLY ESCALATION OF communities in Arakan/Rakhine State. VIOLENCE DEVASTATES ARAKAN • Burma blocks aid agencies from delivering STATE vital supplies of food, water and medicine to 2.The government response civilians in Arakan State. 2.The military response • Tatmadaw burns Rohingya villages and opens 4.Humanitarian crisis fire on their residents without distinguishing 4.Refugee crisis between insurgents and civilians. The govt 5.Escalation of violence and instability orders media to describe the insurgents as 6.Backdrop of anti-Muslim discrimination “terrorists” or face action. 7.Maungdaw economic zone 8.Advisory Commission on Rakhine State • UNHCR estimates over 270,000 new Rohingya releases final report refugees crossed the Burma-Bangladesh border 8.National Commission on violence in between 25 August and 8 September. Maungdaw denies abuses against Rohingya • India plans to deport all Rohingya, including HUMAN RIGHTS those registered as refugees with UNHCR. 9.Tatmadaw arrests former child soldier • The Annan Commission releases its final 9.Telecommunications Law report, urging the Burmese govt to implement 10.No relocation for dangerous sulfuric its recommendations to bring peace to Arakan factory State.