A Discussion on the New Zealand Short Story (3)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The One Story and the Four Ways of Telling

The One Story and the Four Ways of Telling: The relationship between New Zealand literary autobiography and spiritual autobiography. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts in English in the University of Canterbury DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH UN!VEf,SITY OF c,wrrnmnw By CHRISTCHURCH, N.Z. Emily Jane Faith University of Canterbury 2001 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank everyone who has given various forms of support during this two year production. Thanks especially to my Mum and Dad and my brother Nick, Dylan, my friends, and my office-mates in Room 320. Somewhere between lunch, afternoon tea, and the gym, it finally got done! A special mention is due to my supervisor Patrick Evans for his faith in me throughout. The first part of my title is based on Lawrence Jones' a1iicle 'The One Story, the Two Ways of Telling, and the Three Perspectives', in Ariel 16:4 (October 1985): 127-50. CONTENTS Abst1·act ................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 2 I. A brief history of a brief history: New Zealand literary autobiography (and biography) ................................................................................ 2 II. The aims and procedures of this thesis ................................................... 9 III. Spiritual autobiography: the epiphany ................................................. -

Download Download

Figures from the Past: Sargeson‟s Wandering Men and the Limits of Nationalism1 PHILIP STEER It is time to forget about his being a ‘national’ writer, certainly time to cease thinking of him as a ‘realist’. Think instead of affinities with another ‘colonial’ writer[.] Frank Sargeson, „Henry Lawson: Some Notes after Re-Reading‟ Frank Sargeson‟s repositioning of Henry Lawson as a „colonial‟ writer, away from the more familiar categories of nationalism and realism, offers a provocation for re-considering his own short fiction. In taking up that challenge, this essay diverges from recent attempts to trouble the periodization of writing from the 1930s and 40s: rather than arguing that the concerns of cultural nationalism were anticipated in the nineteenth-century, it will make the case that colonial literary forms and cultural formations persist in some of the most familiar works of that later period. Focusing on Sargeson‟s frequent recourse to solitary male characters in his short stories, I will begin by suggesting that their geographic mobility and nostalgic tendencies mark them as anachronistic „figures from the past‟, lacking any social or economic place within contemporary society. The formal contours of the short story are silently troubled by such figures, for as the story „Last Adventure‟ makes especially clear, their realist aesthetic is underpinned by an episodic and anecdotal structure that refract the nineteenth-century adventure romance. Sargeson‟s critical writings on Australian subjects help bring these vestigial traces of the romance productively into focus as formal reflections of broader trans-Tasman linkages of labour, politics and culture that were by the 1930s beginning to seem untenable and unimaginable. -

ENGL 234 New Zealand Literature

English Programme School of English, Film, Theatre, & Media Studies Te Kura Tānga Kōrero Ingarihi, Kiriata, Whakaari, Pāpāho ENGL 234 New Zealand Literature Trimester 1 2010 1 March to 4 July 2010 20 Points TRIMESTER DATES Teaching dates: 1 March 2010 to 4 June 2010 Mid‐trimester break: 5 April to 18 April 2010 Study week: 7 June to 11 June 2010 Examination/Assessment period: 11 June to 4 July 2010 Note: Students who enrol in courses with examinations are expected to be able to attend an examination at the University at any time during the formal examination period. WITHDRAWAL DATES Information on withdrawals and refunds may be found at http://www.victoria.ac.nz/home/admisenrol/payments/withdrawlsrefunds.aspx NAMES AND CONTACT DETAILS Staff Email Phone Room Mark Williams (MW) [email protected] 463 681 VZ 911 Peter Whiteford (PW) [email protected] 463 6820 VZ 801 Kathryn Walls (KW) [email protected] 463 6898 VZ 905 Jane Stafford (JS) [email protected] 463 6816 VZ 901 Lydia Wevers (LW) [email protected] 463 6334 Stout Centre CLASS TIMES AND LOCATIONS Lectures Mon, Tues, Thurs 1510‐1600 Hunter Lecture Theatre 323 COURSE DELIVERY There will be three lectures and one tutorial per week. Tutorial times to be advised. The tutorials are a very important part of your development in the subject, and you should prepare fully for them. Times and rooms are arranged during the first week and posted on the English Section notice‐board 1 School of English, Film, Theatre, & Media Studies ENGLISH PROGRAMME COURSE OUTLINE ENGL 234 and on Blackboard by Friday 5 March. -

![Frank Sargeson [Norris Frank Davey], 1903 – 1982](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9917/frank-sargeson-norris-frank-davey-1903-1982-2919917.webp)

Frank Sargeson [Norris Frank Davey], 1903 – 1982

157 Frank Sargeson [Norris Frank Davey], 1903 – 1982 Lawrence Jones ‘It is not often a writer can be said to have become a symbol in his own lifetime. It is this quality of your achievement that has prompted us to remember this present occasion’. So Frank Sargeson’s fellow New Zealand fiction-writers ended ‘A Letter to Frank Sargeson’, published in Landfall in March 1953 to mark his fiftieth birthday. They were affirming his status as the most significant writer of prose fiction to emerge from that generation that began in the 1930s to create a modern New Zealand Literature. They were celebrating him first as the creator of the New Zealand critical realist short story and short novel, the writer who provided the literary model with which most of those signing the letter had started. But they were also celebrating him as a symbol and a model not only for what he wrote but for where and how he wrote it. In the editorial ‘Notes’ to that same issue of Landfall Charles Brasch stated of Sargeson that ‘by his courage and his gifts he showed that it was possible to be a writer and contrive to live, somehow, in New Zealand, and all later writers are in his debt’. Not only did he show by his example that it was possible to be a serious New Zealand writer without becoming an expatriate, but as mentor and encourager he fostered the careers of a whole generation of fiction writers. At least two of those who signed the letter (Janet Frame and Maurice Duggan) had even lived or were to live in the army hut behind his cottage for a time when they needed the place of refuge and the encouragement, Duggan in 1950 and again in 1958, Frame in 1955-1956. -

HISTORY OR GOSSIP? C.K. STEAD the University of Auckland Free

HISTORY OR GOSSIP? C.K. STEAD The University of Auckland Free Public Lecture Auckland Writers Festival 2019 How do literary history and literary gossip differ? On p. 386 of his biography of Frank Sargeson, Michael King reports that in 1972 Frank ‘had another spirited exchange of letters with Karl Stead when Stead reported that [Charles] Brasch had visited him in Menton.’ I had more or less accused Brasch of being an old fake and asked why everyone was so pious about him. In terms of what it was acceptable to say about Brasch at the time, when he was well known as almost the only wealthy benefactor the Arts in New Zealand had, this was outrageous – and no doubt unfair and unjust. Brasch was a good man who did his best for literature and the visual Arts. But he was irritatingly precious, and snobbish – not the snobbishness of wealth and social status, but of ‘good taste’. He suffered from an overload of discriminations and dismissals – and these had no doubt provoked my ‘spirited’ (to use Michael King’s word) outburst in the letter to Frank. Frank wrote back to me, ‘Look you simply can’t write things like that.’ He reminded me that his correspondence was being bought by the Turnbull Library – in other words his papers were becoming literary history, and if he had not rescued me by sending my letter back, I would have gone on record as having said Bad things about Brasch! King records that my reply was, ‘I wrote to you, Frank, not to the Turnbull Library, or to The Future.’ 1 But this was a reminder that when you put pen to paper or fingers to keyboard, if you are an aspirant to literature, you may be committing literary history. -

„And So He Died As He Had Lived, in Exile and Alone‟: Friendship, Narrative and the Politics of Remembering

„And So He Died as He Had Lived, in Exile and Alone‟: Friendship, Narrative and the Politics of Remembering CHRISTOPHER BURKE Friends were quick to mark the passing of New Zealand novelist James Courage when he died in London in 1963. Courage (1903-63) had found popular and critical acclaim in Britain and elsewhere. This was an accomplishment that few others of his generation had matched. Still fewer, perhaps only Takapuna-based writer Frank Sargeson, could claim to have the attained even a modicum of his success internationally. All of Courage‟s novels had been published in England. A good many had also been printed in the United States and Europe. Courage‟s friends implied, however, that this success – eight novels in three decades – not to mention numerous short stories, poems and a London-based play – had been bought at great personal cost. Courage had died just two years after his homosexual novel, A Way of Love, was withdrawn from circulation in New Zealand. Courage‟s friends suggested he had died in exile: without friends, without even a place in the world. As friend and fellow writer, Phillip Wilson stated, Courage had „died as he had lived, in exile and alone‟.1 The narrative of „Courage as exile‟ had little bearing on the reality of his lived experience. Courage was not an „expatriate‟ in these reminiscences, a term which implies at least some semblance of personal agency. Rather, Courage‟s status as a homosexual combined with – and also reinforced – assertions about New Zealand‟s purported puritanism. Wilson wrote, for example, how Courage‟s „roots‟ were in New Zealand, and that the Antipodes continued to be the source of the writer‟s creativity and imagination. -

Janet Frame's

The City and the Growth of New Zealand Fiction: Janet Frame’s ‘Miss Gibson and the Lumber Room’ Ian Richards 大阪市立大学大学院文学研究科英米言語文化教室 One of the most remarkable cultural developments in the twentieth century was the growth of a large number of new literatures in newly developing independent nations, now referred to as group as Post-colonial literature. Arguably, the most successful case is that of the United States of America, which was the first country to become colonised and gain independence. America now has a body of literature so well established that few, if any, academics consider it when using terms such as Post-colonialism. But this emergence from self-consciousness is relatively new—as recently as the publication of Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March in 1953 critics were still inclined to talk about the establishment of the American novel and of an American voice. America has successfully managed the task of taking literary genres from the European metropolises and putting into those genres its own characters, plots and themes, and in the process it has made any changes to the adopted form that might be necessary. New Zealand is the youngest and among the smallest of the 56 former British colonies, and its literature is largely a twentieth-century phenomenon. It may be no surprise, then, that in New Zealand fiction the short story has developed first and become the most advanced fictional form. Critics have noticed New Zealand’s ‘longstanding preference for the short story’ and have ascribed this to difficulties with -

C. K. Stead – Introduction for the Poetry Archive

This work has been submitted to NECTAR, the Northampton Electronic Collection of Theses and Research. Article Title: C.K. Stead Creators: Kimber, G. Example citation: Kimber, G. (2012) C.K. Stead. Poetry Archive. R[Online] Version: Accepted version A Official URL: http://www.poetryarchive.org/poetryarchive/singlePoet.do? poetId=16152 T http://nectarC.northampton.ac.uk/4943/ NE C. K. Stead – Introduction for The Poetry Archive ‘I think of writing a poem as putting oneself in the moment, at the moment – an action more comprehensive, intuitive and mysterious than mere thinking . .’ C(hristian) K(arlson) Stead, b. Auckland, New Zealand, 1932, Emeritus Professor at Auckland University, is perhaps New Zealand’s most internationally celebrated writer, with a literary life spanning more than fifty years as a poet, novelist, academic and critic. He is the author of eleven novels, fourteen volumes of poetry, two volumes of stories and several works of criticism. He has been the recipient of many prestigious awards honouring his services to literature, including a CBE in 1985, and in 2007 New Zealand’s highest honour, the Order of New Zealand. His work has been translated into many languages, and his output continues to win international accolades: his story ‘Last Season’s Man’ won the first Sunday Times EFG Private Bank Short Story Award in 2010 and a prize of £25,000 – the largest prize in the world to date for a short story. Also in 2010, in somewhat of an annus mirabilis for Stead, and proving that age has not diminished his creative talents, his poem ‘Ischemia’ won the inaugural 2010 International Hippocrates Prize for Poetry and Medicine, a prize of £5,000. -

Takapuna Beach

5 day boarding at King’s. The best of both worlds. Takapuna, Milford, Castor Bay, Forrest Hill and Sunnynook kingscollege.school.nz DELIVERED FORTNIGHTLY Issue 1 – 15 March 2019 AN INDEPENDENT VOICE DELIVEREDDELIVERED FORTNIGHTLDELIVERED FORTNIGHTLY FORTNIGHTLY IssueY 1 – 15 MarIssuechIssue 122019 – Aug1 – 15Issue 16, Mar 2019 1ch – 152019 MarchAN 2019 INDEPENDENTAN V INDEPENDENTOICEAN INDEPENDENT VOICE VOICE Forrest Hill and North Shore Tales told of Takapuna’s Westlake orchestra wins football merger fails... p3 Frank Sargeson... p4 Australasian contest... p21 Takapuna Beach ‘one of city’s worst’ Takapuna Beach is one of the worst more often than the summer before, but only north end was swimmable for about 83 per beaches in Auckland for faecal pollution, because there was low rainfall, Safeswim cent of last summer, while the south end according to the council. manager Nick Vigar told a community was safe for 90 to 95 per cent of the time. Estimates for the most recent summer workshop. The beach behaves differently In the 2017/18 summer, the beach was show the beach was safe for swimming at the north and south ends, Vigar said. The To page 2 Westlakes wig out in Les Miserables Best seat in the house... Mini Clements-Levi (Madame Thenardier) sits on Colby Wilson (Monsieur Thenardier) in Westlake schools’ Les Miserables. Story and more pictures, page 22. THE RANGITOTO OBSERVER PAGE 2 AUGUST 16, 2019 From page 1 Takapuna Beach ‘often unsafe’ due to contamination unsafe for swimming, due to faecal contam- the SafeSwim programme, because it is one being relined. ination, for 30 per cent of the time. -

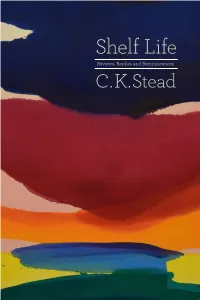

Shelf Life Reviews, Replies and Reminiscences C.K.Stead What Ghost Was Being Appeased? What Wrong Was Being Righted Or Sin Atoned For? I Didn’T Know

Shelf Life Reviews, Replies and Reminiscences C.K.Stead What ghost was being appeased? What wrong was being righted or sin atoned for? I didn’t know. It was all, this writing business – and had been since it first began when I was still at school – mysterious, possibly even neurotic. I knew only that for a moment the world which ‘out there’ seemed so imperfect, so ‘fallen’, so much less than the heart desired, ‘in here’ had been called to order. Every morning for the last thirty years, C. K. Stead has written fiction and poetry. Shelf Life collects the best of his afternoon work: reviews and essays, letters and diaries, lectures and opinion pieces. In this latest collection, a sequel to the successful Answering to the Language, The Writer at Work, and Book Self, Stead takes the reader through nine essays in ‘the Mansfield file’, collects works of criticism and review in ‘book talk’, writes in the ‘first person’ about everything from David Bain to Parnell, and finally offers some recent reflections on poetic laurels from his time as New Zealand poet laureate. Throughout, Stead is vintage Stead: clear, direct, intelligent, decisive, personal. C. K. Stead was born in Auckland in 1932. From the late 1950s, he began to earn an international reputation as a poet and literary critic and, later, as a novelist. He has published more than 40 books and received numerous prizes and honours recognising his contri- bution to literature, including in 2009 the Prime Minister’s Award for Fiction and the Montana New Zealand Book Award (Reference and Anthology) for his Collected Poems and in 2010 the Sunday Times EFG Private Bank Short Story Award and the Hippocrates Prize for Poetry and Medicine. -

Greville Texidor, Frank Sargeson and New Zealand Literary Culture in the 1940S

All the juicy pastures: Greville Texidor, Frank Sargeson and New Zealand literary culture in the 1940s by Margot Schwass A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Victoria University of Wellington 2017 ABSTRACT The cultural nationalist narrative, and the myths of origin and invention associated with it, cast a long shadow over the mid-twentieth century literary landscape. But since at least the 1980s, scholars have turned their attention to what was happening at the margins of that dominant narrative, revealing untold stories and evidence of unexpected literary meeting points, disruptions and contradictions. The nationalist frame has thus lost purchase as the only way to understand the era’s literature. The 1940s in particular have emerged as a time of cultural recalibration in which subtle shifts were being nourished by various sources, not least the émigré and exilic artists who came to New Zealand from war-torn Europe. They included not only refugees but also a group of less classifiable wanderers and nomads. Among them was Greville Texidor, the peripatetic Englishwoman who transformed herself into a writer and produced a small body of fiction here, including what Frank Sargeson would call “one of the most beautiful prose works ever achieved in this country” (“Greville Texidor” 135). The Sargeson-Texidor encounter, and the larger exilic-nationalist meeting it signifies, is the focus of this thesis. By the early 1940s, Sargeson was the acknowledged master of the New Zealand short story, feted for his ‘authentic’ vision of local reality and for the vernacular idiom and economical form he had developed to render it. -

Speaking Frankly

Speaking Frankly Fiona Martin Speaking Frank!J: The Frank Sargeson Memorial Lectures 2003-2010, ed. by Sarah Shieff (Devonport: Cape Catley Ltd., 2011). Speaking Frank!J represents the collected texts for The Frank Sargeson Memorial Lectures, convened by Sarah Shieff, each of which was delivered at The University of Waikato in Hamilton between 2003 and 2010. The lectures included in this volume cover a range of perspectives on Sargeson as a writer, a mentor and a friend; as Shieff observes, these talks 'allow us to celebrate New Zealand writing', of which Sargeson's contribution is a 'signal, laconic, glorious example' (p. 8). In the first lecture, 'A Conversation with my Uncle: Frank Sargeson and Hamilton' (2003), Michael King explores the influence of the city of Hamilton on Sargeson. He notes the 'suffocating Puritanism' (p. 18) of Sargeson's upbringing; his change of name in 1931 from Norris Davey and his subsequent emergence as a 'would-be writer' (p. 16); he considers Sargeson's conscious rejection of Hamilton, but also his use of his early experiences in the city as the imaginative basis of a number of his short stories (p. 18). The importance of place is also acknowledged in Kevin Ireland's lecture, 'Mr Sargeson at Home: A Glimpse at the Domestic Arrangements and Literary Carry-on at 14 Esmonde Road, Takapuna' (2005), as well as in that of Peter Wells, 'The Hole in the Hedge: Landscape and the Fragility of Memory' (2006). Ireland evokes the 'literary oasis' that was Sargeson's residence at Takapuna, and also recalls 'several very different Sargesons', including childhood memories of when Sargeson was 181 Journal of New Zealand Literature a neighbour (pp.