Speaking Frankly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Writing Life Twelve New Zealand Authors DEBORAH SHEPARD

Intelligent, relevant books for intelligent, inquiring readers The Writing Life Twelve New Zealand Authors DEBORAH SHEPARD CANDID CONVERSATIONS WITH 12 WRITERS WHO HELPED SHAPE NEW ZEALAND LITERATURE A unique, candid and intimate survey of the life and work of 12 of our most acclaimed writers: Patricia Grace, Tessa Duder, Owen Marshall, Philip Temple, David Hill, Joy Cowley, Vincent O’Sullivan, Albert Wendt, Marilyn Duckworth, Chris Else, Fiona Kidman and Witi Ihimaera. Constructed as Q&As with experienced oral historian Deborah Shepard, they offer a marvellous insight into their careers. As a group they are now the ‘elders’ of New Zealand literature; they forged the path for the current generation. Together the authors trace their publishing and literary history from 1959 to 2018, through what might now be viewed as a golden era of publishing into the more unsettled climate of today. They address universal themes: the death of parents and loved ones, the good things that come with ageing, the components of a satisfying life, and much more. And they give advice on writing. The book has an historical continuity, showing fruitful and fascinating links $49.99 between individuals who have negotiated the same literary terrain for more than sixty years. To further honour them are magnificent photo portraits by CATEGORY: New Zealand Non Fiction distinguished photographer John McDermott, commissioned by the publisher ISBN: 978-0-9951095-3-7 for this project. eISBN: n/a ABOUT THE AUTHOR BIC: BGL, DSK, 1MBN BISAC: LCO020000, BIO007000 Deborah Shepard is an author, teacher of memoir, oral historian and film PUBLISHER: Massey University Press and art historian. -

The One Story and the Four Ways of Telling

The One Story and the Four Ways of Telling: The relationship between New Zealand literary autobiography and spiritual autobiography. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts in English in the University of Canterbury DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH UN!VEf,SITY OF c,wrrnmnw By CHRISTCHURCH, N.Z. Emily Jane Faith University of Canterbury 2001 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank everyone who has given various forms of support during this two year production. Thanks especially to my Mum and Dad and my brother Nick, Dylan, my friends, and my office-mates in Room 320. Somewhere between lunch, afternoon tea, and the gym, it finally got done! A special mention is due to my supervisor Patrick Evans for his faith in me throughout. The first part of my title is based on Lawrence Jones' a1iicle 'The One Story, the Two Ways of Telling, and the Three Perspectives', in Ariel 16:4 (October 1985): 127-50. CONTENTS Abst1·act ................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 2 I. A brief history of a brief history: New Zealand literary autobiography (and biography) ................................................................................ 2 II. The aims and procedures of this thesis ................................................... 9 III. Spiritual autobiography: the epiphany ................................................. -

The Robert Burns Fellowship 2020

THE ROBERT BURNS FELLOWSHIP 2020 The Fellowship was established in 1958 by a group of citizens, who wished to remain anonymous, to commemorate the bicentenary of the birth of Robert Burns and to perpetuate appreciation of the valuable services rendered to the early settlement of Otago by the Burns family. The general purpose of the Fellowship is to encourage and promote imaginative New Zealand literature and to associate writers thereof with the University. It is attached to the Department of English and Linguistics of the University. CONDITIONS OF AWARD 1. The Fellowship shall be open to writers of imaginative literature, including poetry, drama, fiction, autobiography, biography, essays or literary criticism, who are normally resident in New Zealand or who, for the time being, are residing overseas and who in the opinion of the Selection Committee have established by published work or otherwise that they are a serious writer likely to continue writing and to benefit from the Fellowship. 2. Applicants for the Fellowship need not possess a university degree or diploma or any other educational or professional qualification nor belong to any association or organisation of writers. As between candidates of comparable merit, preference shall be given to applicants under forty years of age at the time of selection. The Fellowship shall not normally be awarded to a person who is a full time teacher at any University. 3. Normally one Fellowship shall be awarded annually and normally for a term of one year, but may be awarded for a shorter period. The Fellowship may be extended for a further term of up to one year, provided that no Fellow shall hold the Fellowship for more than two years continuously. -

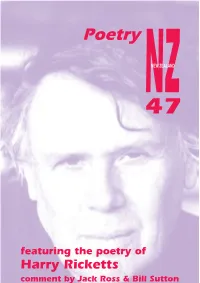

PNZ 47 Digital Version

Poetry NZNEW ZEALAND 47 featuring the poetry of 1 Harry Ricketts comment by Jack Ross & Bill Sutton Poetry NZ Number 47, 2013 Two issues per year Editor: Alistair Paterson ONZM Submissions: Submit at any time with a stamped, self-addressed envelope (and an email address if available) to: Poetry NZ, 34B Methuen Road, Avondale, Auckland 0600, New Zealand or 1040 E. Paseo El Mirador, Palm Springs, CA 92262-4837, USA Please note that overseas submissions cannot be returned, and should include an email address for reply. Postal subscriptions: Poetry NZ, 37 Margot Street, Epsom, Auckland 1051, New Zealand or 1040 E. Paseo el Mirador, Palm Springs, CA 92262-4837, USA Postal subscription Rates: US Subscribers (by air) One year (2 issues) $30.00 $US24.00 Two years (4 issues) $55.00 $US45.00 Libraries: 1 year $32.00 $US25.00 Libraries: 2 years $60.00 $US46.00 Other countries One year (2 issues) $NZ36.00 Two years (4 issues) $NZ67.00 Online subscriptions: To take out a subscription go to www.poetrynz.net and click on ‘subscribe’. The online rates are listed on this site. When your subscription application is received it will be confi rmed by email, and your fi rst copy of the magazine will then be promptly posted out to you. 2 Poetry NZ 47 Alistair Paterson Editor Puriri Press & Brick Row Auckland, New Zealand Palm Springs, California, USA September 2013 3 ISSN 0114-5770 Copyright © 2013 Poetry NZ 37 Margot Street, Epsom, Auckland 1051, New Zealand All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo copying, recording or otherwise without the written permission of the publisher. -

Dissertation

DISSERTATION Titel der Dissertation „‘Kiwi’ Masculinities in New Zealand Short Stories“ Verfasserin MMag. phil. Maria Hinterkörner angestrebter akademischer Grad Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt : A 092 343 Dissertationsgebiet lt. Studienblatt: Anglistik und Amerikanistik Betreuerin: Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Astrid Fellner [i] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS “‘[New Zealand] is not quite the moon, but after the moon it is the farthest place in the world,’” said Sir Karl Popper (as quoted in KING 2003: 415), Austrian-New Zea- land-British philosopher; and ‘off the edge of the world’ in unlikely Kawakawa is where Friedensreich Hundertwasser built a colourful public toilet after having abandoned Austria for the sheep-crowded archipelago in the South Pacific. Little did I know about New Zealand as a country, as a people, as a nation and – above all – about how to pen a doctoral dissertation when I set out on this scien- tific journey a little while ago. At a very early stage of my doctoral endeavours, I knew my inquisitiveness could not be satisfied with the holdings at the University of Vienna, Austria, a country on the opposite side of the earth of the country’s lit- erature that I had chosen as subject of investigation. I was lucky enough to call Aotearoa/New Zealand my home for six months in 2009 – a sojourn that proved most fecund to my work, provided me with an abundance of motivation, and left me awe-inspired by the country’s inhabitants – scholars, fishermen, tattooists – its natural beauty and its rich and colourful culture. I was able to spend most of my time in the immense libraries of New Zealand’s universities and in conversation with scholars and authors who so very openly supported my work and provided answers where clarity had yet been missing. -

THE INKLINGS – Christmas 20, Issue No. 14

THE INKLINGS – Christmas 20, Issue No. 14 Amazing Navigating the State Highway Down South Hiakai: Modern Ko Aotearoa Aroha: Māori Birds of Aotearoa Aotearoa Stars: Māori One BRUCE ANSLEY Māori Cuisine Tātou I We Are wisdom for a New Zealand: Activity Book Creation Myths SAM COLEY (HARPERCOLLINS) MONIQUE FISO New Zealand contented life Collective Nouns GAVIN BISHOP WITI IHIMAERA (HACHETTE LIVRE) HB NZ TITLE (GODWIT) MICHELLE ELVY, lived in harmony MELISSA (PENGUIN BOOKS) (VINTAGE NZ) PB NZ TITLE $49.99 HB NZ TITLE PAULA MORRIS, with our planet BOARDMAN PB NZ TITLE HB NZ TITLE $34.99 From Curio Bay to $65.00 JAMES NORCLIFFE HINEMOANA (HARPERCOLLINS) $25.00 $45.00 It's been years since Golden Bay, writer After years overseas in (OTAGO ELDER (PENGUIN HB NZ TITLE UNIVERSITY PRESS) There are 60+ awe- From master storyteller Alex was in New Bruce Ansley sets Michelin-star restau- BOOKS) $29.99 NZ TITLE some games, puz- Witi Ihimaera, a spell- Zealand, and years off on a vast expe- rants, Monique Fiso PB HB NZ TITLE A whistling of whio? zles and activities in binding and provocative since he spent any one- dition across the returned to Aotearoa to $39.95 $30.00 A loot of weka? A tus- this fun, creative and retelling of traditional on-one time with his South Island, Te begin Hiakai, an inno- Ko Aotearoa Tātou | Discover traditional sock of takahē? This We Are New Zealand is high-quality activity Māori myths for the twin sister, Amy. When Waipounamu, visiting vative pop-up venture Māori philosophy is a book for children, book based on Gavin twenty-first century. -

A Critical Evaluation of New Zealand's Antactic Art Programmes

A critical evaluation of New Zealand’s Antarctic art programmes, 1957-2011 ANTA 604 Tim Jones February 2011 1 Table of Conents Table of Conents................................................................................................................... 2 Abstract ................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 4 Part one – the artists ............................................................................................................ 5 Part two – the programmes................................................................................................ 51 Part three – the art .............................................................................................................. 58 Conclusions ........................................................................................................................ 66 Acknowledgments .............................................................................................................. 67 2 Abstract The author considers the programmes that have enabled artists to travel to Antarctica as part of the New Zealand Antarctic programme between 1957 and 2011. Details of artists and their visits are given, followed by a descriptive history of the artist programme itself, outlining its origins, development and current status. Finally the artists’ opinions -

Tina Makereti, the Novel Sleeps Standing About the Battle of Orakau and Native Son, the Second Volume of His Memoir

2017 AUTHOR Showcase AcademyAcademy ofof NewNew Zealand Zealand Literature Literature ANZLANZLTe WhareTe Whare Mātātuhi Mātātuhi o Aotearoa o Aotearoa Please visit the Academy of New Zealand Literature web site for in-depth features, interviews and conversations. www.anzliterature.com Academy of New Zealand Literature ANZL Te Whare Mātātuhi o Aotearoa Academy of New Zealand Literature ANZL Te Whare Mātātuhi o Aotearoa Kia ora festival directors, This is the first Author Showcase produced by the Academy of New Zealand Literature (ANZL). We are writers from Aotearoa New Zealand, mid-career and senior practitioners who write fiction, poetry and creative nonfiction. Our list of Fellows and Members includes New Zealand’s most acclaimed contemporary writers, including Maurice Gee, Keri Hulme, Lloyd Jones, Eleanor Catton, Witi Ihimaera, C.K. Stead and Albert Wendt. This showcase presents 15 writers who are available to appear at literary festivals around the world in 2017. In this e-book you’ll find pages for each writer with a bio, a short blurb about their latest books, information on their interests and availability, and links to online interviews and performances. Each writer’s page lists an email address so you can contact them directly, but please feel free to contact me directly if you have questions. These writers are well-known to New Zealand’s festival directors, including Anne O’Brien of the Auckland Writers Festival and Rachael King of Word Christchurch. Please note that New Zealand writers can apply for local funding for travel to festivals and other related events. We plan to publish an updated Author Showcase later this year. -

A Discussion on the New Zealand Short Story (3)

A Discussion on the New Zealand Short Story (3) 江 澤 恭 子* A Discussion on the New Zealand Short Story (3) Kyoko EZAWA The second short story is another of Sargeson’s narratives, entitled Cow-Pats. This too is a very short story, one page and a half, written in an easy, simple style. In spite of its shortness, as far as I know, it characterises New Zealand. In the cold morning of winter, one of“my” brothers working on the dairy farm‘found out a good way of warming his feet up. He stuck them -gum-boots- into a cow-pat that had just been dropped,1 ) and he said it made his feet feel bosker and warm .... So we’d watch out, and whenever a cow dropped a nice big pat we’d race for it, and the one who got there first wouldn’t let the others put their feet in.’ One early cold morning, at the hotel,“I” -the youngest boy- saw:‘Just as the porter was finishing -cleaning- the steps an old man came along the street and asked if he could warm his hands up in the bucket of water ... so he kept them there until they were warm.’‘Well, that was something I understood without having to ask any questions.’ Thus the boy realised, through strange and rare experiences, what living is. The next-to-last work in this series of essays is Vincent O’Sullivan’s Grove. Grove is a plotless story. It begins in a very simple manner with an external explanation of Grove’s face without any preliminary knowledge of him. -

Download Download

Figures from the Past: Sargeson‟s Wandering Men and the Limits of Nationalism1 PHILIP STEER It is time to forget about his being a ‘national’ writer, certainly time to cease thinking of him as a ‘realist’. Think instead of affinities with another ‘colonial’ writer[.] Frank Sargeson, „Henry Lawson: Some Notes after Re-Reading‟ Frank Sargeson‟s repositioning of Henry Lawson as a „colonial‟ writer, away from the more familiar categories of nationalism and realism, offers a provocation for re-considering his own short fiction. In taking up that challenge, this essay diverges from recent attempts to trouble the periodization of writing from the 1930s and 40s: rather than arguing that the concerns of cultural nationalism were anticipated in the nineteenth-century, it will make the case that colonial literary forms and cultural formations persist in some of the most familiar works of that later period. Focusing on Sargeson‟s frequent recourse to solitary male characters in his short stories, I will begin by suggesting that their geographic mobility and nostalgic tendencies mark them as anachronistic „figures from the past‟, lacking any social or economic place within contemporary society. The formal contours of the short story are silently troubled by such figures, for as the story „Last Adventure‟ makes especially clear, their realist aesthetic is underpinned by an episodic and anecdotal structure that refract the nineteenth-century adventure romance. Sargeson‟s critical writings on Australian subjects help bring these vestigial traces of the romance productively into focus as formal reflections of broader trans-Tasman linkages of labour, politics and culture that were by the 1930s beginning to seem untenable and unimaginable. -

MODERN LETTERS Te P¯U Tahi Tuhi Auaha O Te Ao

INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF MODERN LETTERS Te P¯u tahi Tuhi Auaha o te Ao Newsletter – 28 March 2008 This is the 121 st in a series of occasional newsletters from the Victoria University centre of the International Institute of Modern Letters. For more information about any of the items, please email [email protected] 1. We have a winner!.............................................................................................. 1 2. Life across the Tasman........................................................................................ 2 3. Muldooniana....................................................................................................... 2 4. A Spanish story.................................................................................................... 2 5. And still on the subject of writers’ festivals . .................................................. 3 6. Newsflash ............................................................................................................ 3 7. Best New Zealand Poems.................................................................................... 3 8. From the whiteboard.......................................................................................... 3 9. Writing on the run.............................................................................................. 3 10. Online pioneers ................................................................................................. 3 11. The expanding bookshelf................................................................................. -

ENGL 234 New Zealand Literature

English Programme School of English, Film, Theatre, & Media Studies Te Kura Tānga Kōrero Ingarihi, Kiriata, Whakaari, Pāpāho ENGL 234 New Zealand Literature Trimester 1 2010 1 March to 4 July 2010 20 Points TRIMESTER DATES Teaching dates: 1 March 2010 to 4 June 2010 Mid‐trimester break: 5 April to 18 April 2010 Study week: 7 June to 11 June 2010 Examination/Assessment period: 11 June to 4 July 2010 Note: Students who enrol in courses with examinations are expected to be able to attend an examination at the University at any time during the formal examination period. WITHDRAWAL DATES Information on withdrawals and refunds may be found at http://www.victoria.ac.nz/home/admisenrol/payments/withdrawlsrefunds.aspx NAMES AND CONTACT DETAILS Staff Email Phone Room Mark Williams (MW) [email protected] 463 681 VZ 911 Peter Whiteford (PW) [email protected] 463 6820 VZ 801 Kathryn Walls (KW) [email protected] 463 6898 VZ 905 Jane Stafford (JS) [email protected] 463 6816 VZ 901 Lydia Wevers (LW) [email protected] 463 6334 Stout Centre CLASS TIMES AND LOCATIONS Lectures Mon, Tues, Thurs 1510‐1600 Hunter Lecture Theatre 323 COURSE DELIVERY There will be three lectures and one tutorial per week. Tutorial times to be advised. The tutorials are a very important part of your development in the subject, and you should prepare fully for them. Times and rooms are arranged during the first week and posted on the English Section notice‐board 1 School of English, Film, Theatre, & Media Studies ENGLISH PROGRAMME COURSE OUTLINE ENGL 234 and on Blackboard by Friday 5 March.