Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE POLISH POLICE Collaboration in the Holocaust

THE POLISH POLICE Collaboration in the Holocaust Jan Grabowski The Polish Police Collaboration in the Holocaust Jan Grabowski INA LEVINE ANNUAL LECTURE NOVEMBER 17, 2016 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. First printing, April 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Jan Grabowski THE INA LEVINE ANNUAL LECTURE, endowed by the William S. and Ina Levine Foundation of Phoenix, Arizona, enables the Center to bring a distinguished scholar to the Museum each year to conduct innovative research on the Holocaust and to disseminate this work to the American public. Wrong Memory Codes? The Polish “Blue” Police and Collaboration in the Holocaust In 2016, seventy-one years after the end of World War II, the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs disseminated a long list of “wrong memory codes” (błędne kody pamięci), or expressions that “falsify the role of Poland during World War II” and that are to be reported to the nearest Polish diplomat for further action. Sadly—and not by chance—the list elaborated by the enterprising humanists at the Polish Foreign Ministry includes for the most part expressions linked to the Holocaust. On the long list of these “wrong memory codes,” which they aspire to expunge from historical narrative, one finds, among others: “Polish genocide,” “Polish war crimes,” “Polish mass murders,” “Polish internment camps,” “Polish work camps,” and—most important for the purposes of this text—“Polish participation in the Holocaust.” The issue of “wrong memory codes” will from time to time reappear in this study. -

From "Russian" to "Polish": Vilna-Wilno 1900-1925

FROM “RUSSIAN” TO “POLISH”: Vilna-Wilno 1900-1925 Theodore R. Weeks Southern Illinois University at Carbondale The National Council for Eurasian and East European Research 910 17th Street, N.W. Suite 300 Washington, D.C. 20006 TITLE VIII PROGRAM Project Information* Principal Investigator: Theodore R. Weeks Council Contract Number: 819-06g Date: June 4, 2004 Copyright Information Scholars retain the copyright on works they submit to NCEEER. However, NCEEER possesses the right to duplicate and disseminate such products, in written and electronic form, as follows: (a) for its internal use; (b) to the U.S. Government for its internal use or for dissemination to officials of foreign governments; and (c) for dissemination in accordance with the Freedom of Information Act or other law or policy of the U.S. government that grants the public access to documents held by the U.S. government. Additionally, NCEEER has a royalty-free license to distribute and disseminate papers submitted under the terms of its agreements to the general public, in furtherance of academic research, scholarship, and the advancement of general knowledge, on a non-profit basis. All papers distributed or disseminated shall bear notice of copyright. Neither NCEEER, nor the U.S. Government, nor any recipient of a Contract product may use it for commercial sale. * The work leading to this report was supported in part by contract or grant funds provided by the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research, funds which were made available by the U.S. Department of State under Title VIII (The Soviet-East European Research and Training Act of 1983, as amended). -

Collectiones Museorum Manuscripta Castreniana Realia II, Ethnographica 1 Travaux Ethnographiques De La Société Finno-Ougrienne XXII

Matthias Alexander Castrén Matthias Alexander Matt hias Alexander Castrén (1813–1852) was by far the most signifi cant Finn- ish linguist of the 19th century. In addition to being a linguist he was also a multidisciplinary scholar, equally versatile in the fi elds of ethnography, folklore, mythology, archaeology, history, and human geography. He left behind a huge corpus of fi eld data, collected by himself during prolonged expeditions to Kare- lia, Lapland, Arctic Russia, and Siberia between 1838 and 1849. In the short peri- ods of time Castrén spent in an academic environment, he had litt le opportunity to synthesize his collections, a situation aggravated by his rapidly progressing and ultimately fatal illness. Th erefore, a major part of his scholarly heritage re- mained unpublished when he died. Castrén was appointed Docent of Finnish and Ancient Nordic Languages and Tribes at the Imperial Alexander University in Helsinki in 1841, and ten years later he became the fi rst Professor of the Finnish Language. M.A. Castrén considered ethnology as a historical science and an instru- ment for describing the early periods of Finnish history. On his expeditions, he carried out ethnographic observations and took notes of the dwellings, cos- tumes, way of life, and customs of indigenous Siberian peoples. According to the programme draft ed by the Imperial Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences, Collectiones museorum Castrén collected ethnological artifacts for the Ethnographic Museum in Saint Petersburg, and some items for the Ethnographic Museum of the University of Helsinki. Th e present work concentrates on the collections which describe Castrén’s merits in ethnological studies and museology. -

1. Charakteristika Kraje a Jeho Postavení V Rámci České Republiky

1. Charakteristika kraje a jeho postavení v rámci České republiky Pardubický kraj leží ve východní části Čech, na severu hraničí s Královéhradeckým krajem, na jihu s krajem Vysočina a s Jihomoravským krajem, na východě s Olomouckým a na západě se Středočeským krajem. Severovýchodní výběžek kraje sousedí také s Polskem. Východní částí kraje, Svitavskem a Moravskotřebovskem, prochází zemská hranice mezi Čechami a Moravou. Území Pardubického kraje se vyznačuje jedním z nejvyšších rozpětí nadmořské výšky mezi všemi kraji v České republice. Střední a západní část kraje je tvořena úrodnou Polabskou nížinou; nejnižší bod (201 m n. m.) přitom leží při západní hranici kraje na hladině Labe u Kojic. Severovýchod území ohraničuje jižní část Orlických hor a nejzápadnější svahy Hrubého Jeseníku. Na jihu a jihovýchodě je území kraje lemováno vrchovinnými oblastmi Žďárských vrchů a Železných hor. Orlické hory, Žďárské vrchy i Železné hory přitom patří mezi chráněné krajinné oblasti. Nejvyšším bodem kraje a jedním z nejvyšších míst České republiky je Králický Sněžník (1 424 m n. m.) ležící v severovýchodním výběžku kraje. Celá oblast Králického Sněžníku byla vyhlášena národní přírodní rezervací. Rozdíly v klimatických podmínkách uvnitř kraje souvisí s výraznými rozdíly nadmořských výšek. V severozápadní nížinné oblasti převažuje teplejší a sušší klima, směrem na východ a k jihu se podnebí mění v chladnější a vlhčí. Na základě údajů Českého hydrometeorologického ústavu dosáhla v letech 2000 – 2005 průměrná roční teplota vzduchu měřená v Pardubicích (stanice letiště; 225 m n. m.) 9,6 ºC; průměrný roční úhrn srážek činil 534,5 mm. V okolí Svratouchu (737 m n. m.) byla ve stejném období průměrná roční teplota vzduchu 6,7 ºC a roční úhrn srážek 804,9 mm. -

The Crime of Genocide Committed Against the Poles by the USSR Before and During World War II: an International Legal Study, 45 Case W

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 45 | Issue 3 2012 The rC ime of Genocide Committed against the Poles by the USSR before and during World War II: An International Legal Study Karol Karski Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Karol Karski, The Crime of Genocide Committed against the Poles by the USSR before and during World War II: An International Legal Study, 45 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 703 (2013) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol45/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 45 Spring 2013 Issue 3 The Crime of Genocide Committed Against the Poles by the USSR Before and During WWII: An International Legal Study Karol Karski Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law·Vol. 45·2013 The Crime of Genocide Committed Against the Poles The Crime of Genocide Committed Against the Poles by the USSR Before and During World War II: An International Legal Study Karol Karski* The USSR’s genocidal activity against the Polish nation started before World War II. For instance, during the NKVD’s “Polish operation” of 1937 and 1938, the Communist regime exterminated about 85,000 Poles living at that time on the pre- war territory of the USSR. -

OECD Territorial Grids

BETTER POLICIES FOR BETTER LIVES DES POLITIQUES MEILLEURES POUR UNE VIE MEILLEURE OECD Territorial grids August 2021 OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities Contact: [email protected] 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Territorial level classification ...................................................................................................................... 3 Map sources ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Map symbols ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Disclaimers .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Australia / Australie ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Austria / Autriche ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Belgium / Belgique ...................................................................................................................................... 9 Canada ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Part II – Existing National Indicators Of

Part IV – Case Study Reports 1. Introduction In this section, we complement the quantitative findings from Part III of this report by selecting ten regions for more in-depth qualitative research. Two primary criteria were employed in the selection of the regions. First, both ‘high QoG’ and ‘low QoG’ regions were intentionally selected. In several cases, such as Bolzano (IT), Västra Götaland (SE) and Pais Vasco (EP), Campania (IT), Norte (PT) and Severozapadan (BG), the regions were ranked on the relatively high or low end of the entire sample of 172 EU regions. In other cases, the regions demonstrated high or low QoG relative to their geographic position in the EU, such as Wallonie (BE), Nord Vest (RO), Estonia and Jihozapad (CZ). The general hope in this more qualitative part of the report was to corroborate the results of the survey data in Part III and to produce findings from both high and low QoG regions from which general advice for other regions can be deduced along with possible specific policy recommendations. Second, a fairly even distribution of EU-15 and New Member States (NMS) was selected. EU-15 regions come from Sweden, Italy, Belgium, Spain and Portugal, while the NMS regions come from Bulgaria, Romania, the Czech Republic and Estonia. This was done to acknowledge the diverse challenges that face regions in different parts of the EU and the relatively different levels of economic and political development observed among the cases. 2. Methodology of the Case Studies The ten case studies in this report follow the same methodology. First, each researcher was assigned a region and gathered background information on demographics, indicators of economic and social development, the EU’s recent impact, and the history and significance of the region. -

Country Compendium

Country Compendium A companion to the English Style Guide July 2021 Translation © European Union, 2011, 2021. The reproduction and reuse of this document is authorised, provided the sources and authors are acknowledged and the original meaning or message of the texts are not distorted. The right holders and authors shall not be liable for any consequences stemming from the reuse. CONTENTS Introduction ...............................................................................1 Austria ......................................................................................3 Geography ................................................................................................................... 3 Judicial bodies ............................................................................................................ 4 Legal instruments ........................................................................................................ 5 Government bodies and administrative divisions ....................................................... 6 Law gazettes, official gazettes and official journals ................................................... 6 Belgium .....................................................................................9 Geography ................................................................................................................... 9 Judicial bodies .......................................................................................................... 10 Legal instruments ..................................................................................................... -

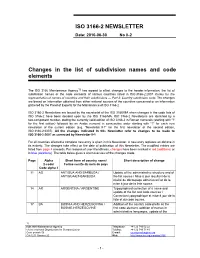

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Changes in the List of Subdivision Names And

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Date: 2010-06-30 No II-2 Changes in the list of subdivision names and code elements The ISO 3166 Maintenance Agency1) has agreed to effect changes to the header information, the list of subdivision names or the code elements of various countries listed in ISO 3166-2:2007 Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions — Part 2: Country subdivision code. The changes are based on information obtained from either national sources of the countries concerned or on information gathered by the Panel of Experts for the Maintenance of ISO 3166-2. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are issued by the secretariat of the ISO 3166/MA when changes in the code lists of ISO 3166-2 have been decided upon by the ISO 3166/MA. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are identified by a two-component number, stating the currently valid edition of ISO 3166-2 in Roman numerals (starting with "I" for the first edition) followed by an Arabic numeral in consecutive order starting with "1" for each new newsletter of the current edition (e.g. "Newsletter II-1" for the first newsletter of the second edition, ISO 3166-2:2007). All the changes indicated in this Newsletter refer to changes to be made to ISO 3166-2:2007 as corrected by Newsletter II-1. For all countries affected a complete new entry is given in this Newsletter. A new entry replaces an old one in its entirety. The changes take effect on the date of publication of this Newsletter. The modified entries are listed from page 4 onwards. -

The Empire, the Nation

“The relationship between empire and nation was among the thorniest of questions in the late Russian Em- pire, and the complications proved most acute in the country’s western regions. This volume assembles a The truly international team of scholars to explore these matters in a range of different contexts, from education Edited by and religion to censorship, tourism, and right-wing political mobilization. The chapters reveal an exception- al set of challenges that statesmen, reformers, and imperial subjects of diverse nationalities and confessions Tsar Darius The faced in conceptualizing and actualizing their projects in the context of new forms of association and al- Staliūnas tered political frameworks. As the authors reveal, the greatest casualty for imperial policy was consistency. Full of new research and compelling insights, The Tsar, the Empire, and the Nation represents the latest , The and word on this important problem in Russian and East European history.” Tsar, —Paul W. Werth, Professor of History, University of Nevada, Las Vegas Yoko “By investigating western borderlands from the Baltic provinces in the north to Ukraine in the south, this Empire Aoshima The Empire, volume creates a meso-level between the macro-perspective on the Russian empire as a whole and the mi- cro-perspective on a single region, paving the ground for comparative insights into the empire’s responses and to national questions. What I admire the most about this book is its very balanced discussion of national questions which still bear the potential to become politicized.” , The Nation —Martin Aust, Professor of History, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn, Germany and Dilemmas of Nationalization his book addresses the challenge of modern nationalism to the tsarist Russian Empire that first ap- Russia’s Western The in Tpeared on the empire’s western periphery. -

Bratislava Region - Tomás Srnka

Bratislava Region - Tomás Srnka Bratislava Region Regions—which are sometimes difficult to depict accurately on maps—may be based on economic activity, climate and topography, cultural history, or location relative to other regions. One region may be defined in terms of the vast desert that dominates its landscape, whilst another may exist because its residents follow a common religion and speak one language, or be dependent on a single agricultural crop. Many regions cross national borders, but others exist entirely within a single state. Despite the difficulties in defining regions precisely, they are extremely useful to geographers because they are based on the meaningful social, cultural, and economic factors that produce a distinctive geographic identity (referaty.sk). Since 1949, Slovakia has been divided into “kraje” (singular "kraj";translated as "Regions"). Their number, borders and functions have been changed several times. Every Regions has been devided in okresy (districts). There are currently 79 districts of Slovakia. Now, Slovakia has 8 Regions: 1. Bratislava Region (Bratislavský kraj) 2. Trnava Region (Trnavský kraj) 3. Trenčín Region (Trenčiansky kraj) 4. Nitra Region (Nitriansky kraj) 5. Žilina Region (Žilinský kraj) 6. Banská Bystrica Region (Banskobystrický kraj) 7. Prešov Region (Prešovský kraj) 8. Košice Region (Košický kraj) Bratislava Region - Tomás Srnka Before 1949, Slovakia was not devided into Regions, but into comitatuses (It was administrative unit in Hungary Kingdom from the 10th century to 1918) (wikipedia.org). Bratislava region is devided into 8 districts: 1. Bratislava I 2. Bratislava II 3. Bratislava III 4. Bratislava IV 5. Bratislava V 6. Malacky District 7. Pezinok District 8. -

Vybrané Údaje O Objektoch SR Podľa Kraj/Okres K 1.1.2020

Odbor cestnej databanky - 2100 VYBRANÉ ÚDAJE O OBJEKTOCH NA SIETI CESTNÝCH KOMUNIKÁCIÍ SR ÚZEMNÉ ČLENENIE: SR - KRAJE Stav siete cestných komunikácií k 1.1.2020 BRATISLAVA, 2020 SPRACOVATEĽ: SLOVENSKÁ SPRÁVA CIEST Odbor cestnej databanky - 2100 Miletičova 19 telefón: 02/50 255 290 826 19 Bratislava fax: 02/55 56 82 68 Zodpovední za spracovanie Ing. Mariannna Králiková kl. 432 [email protected] Anna Šimonová [email protected] Údaje, ktoré sú obsahom tejto publikácie je možné použiť len s uvedením zdroja. Rozmnožovanie obsahu tejto publikácie, ako aj jej jednotlivých častí, v pôvodnej alebo upravenej podobe je možné len s písomným súhlasom Slovenskej správy ciest. Údaje o cestných komunikáciách – Centrálna technická evidencia cestných komunikácií, Cestná databanka, Slovenská správa ciest, stav dát k 01.01.2020. 1/38 OBSAH Strana Obsah ...................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Vysvetlivky (zoznam správcov) ............................................................................................................................... 2 ZÁKLADNÉ ÚDAJE O OBJEKTOCH NA CESTNÝCH KOMUNIKÁCIÁCH ÚZEMNÉ ČLENENIE: SR - KRAJE Počet, dĺžka a plocha objektov podľa druhu objektu, materiálu konštrukcie a dopravného významu CK: SR – dopravný význam CK ........................................................................................................................ 5 Základné údaje o objektoch, graf ..............................................................................................................