1. the Scope of Life Cycles 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicago Board Options Exchange Annual Report 2001

01 Chicago Board Options Exchange Annual Report 2001 cv2 CBOE ‘01 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 CBOE is the largest and 01010101010101010most successful options 01010101010101010marketplace in the world. 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 01010101010101010ifc1 CBOE ‘01 ONE HAS OPPORTUNITIES The NUMBER ONE Options Exchange provides customers with a wide selection of products to achieve their unique investment goals. ONE HAS RESPONSIBILITIES The NUMBER ONE Options Exchange is responsible for representing the interests of its members and customers. Whether testifying before Congress, commenting on proposed legislation or working with the Securities and Exchange Commission on finalizing regulations, the CBOE weighs in on behalf of options users everywhere. As an advocate for informed investing, CBOE offers a wide array of educational vehicles, all targeted at educating investors about the use of options as an effective risk management tool. ONE HAS RESOURCES The NUMBER ONE Options Exchange offers a wide variety of resources beginning with a large community of traders who are the most experienced, highly-skilled, well-capitalized liquidity providers in the options arena. In addition, CBOE has a unique, sophisticated hybrid trading floor that facilitates efficient trading. 01 CBOE ‘01 2 CBOE ‘01 “ TO BE THE LEADING MARKETPLACE FOR FINANCIAL DERIVATIVE PRODUCTS, WITH FAIR AND EFFICIENT MARKETS CHARACTERIZED BY DEPTH, LIQUIDITY AND BEST EXECUTION OF PARTICIPANT ORDERS.” CBOE MISSION LETTER FROM THE OFFICE OF THE CHAIRMAN Unprecedented challenges and a need for strategic agility characterized a positive but demanding year in the overall options marketplace. The Chicago Board Options Exchange ® (CBOE®) enjoyed a record-breaking fiscal year, with a 2.2% growth in contracts traded when compared to Fiscal Year 2000, also a record-breaker. -

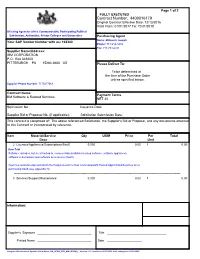

Contract Number: 4400016179

Page 1 of 2 FULLY EXECUTED Contract Number: 4400016179 Original Contract Effective Date: 12/13/2016 Valid From: 01/01/2017 To: 12/31/2018 All using Agencies of the Commonwealth, Participating Political Subdivision, Authorities, Private Colleges and Universities Purchasing Agent Name: Millovich Joseph Your SAP Vendor Number with us: 102380 Phone: 717-214-3434 Fax: 717-783-6241 Supplier Name/Address: IBM CORPORATION P.O. Box 643600 PITTSBURGH PA 15264-3600 US Please Deliver To: To be determined at the time of the Purchase Order unless specified below. Supplier Phone Number: 7175477069 Contract Name: Payment Terms IBM Software & Related Services NET 30 Solicitation No.: Issuance Date: Supplier Bid or Proposal No. (if applicable): Solicitation Submission Date: This contract is comprised of: The above referenced Solicitation, the Supplier's Bid or Proposal, and any documents attached to this Contract or incorporated by reference. Item Material/Service Qty UOM Price Per Total Desc Unit 2 Licenses/Appliances/Subscriptions/SaaS 0.000 0.00 1 0.00 Item Text Software: includes, but is not limited to, commercially available licensed software, software appliances, software subscriptions and software as a service (SaaS). Agencies must develop and attach the Requirements for Non-Commonwealth Hosted Applications/Services when purchasing SaaS (see Appendix H). -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Services/Support/Maintenance 0.000 0.00 -

Java and Z/OS (And Rdz)

® IBM Software Group Java and z/OS (and RDz) Jon Sayles – [email protected] © 2016 IBM Corporation IBM Software Group | Rational software Merrill Class . They’ll have RDz exposure . Terms & Concepts & Vocabulary Remove fear of Java Analogies – Procedural vocabulary 20 – 30 students - mix of young + old (mostly old) dudes . Call COBOL from Java Java doesn’t create an .exe Objects . z/OS Java Standard z/OS environment JCL – pointing to Unix Aware of JVM – can call COBOL http://www.s390java.com/index.htm IBM Software Group | Rational software Trademarks Trademarks The following are trademarks of the International Business Machines Corporation in the United States and/or other countries. For a complete list of IBM Trademarks, see www.ibm.com/legal/copytrade.shtml: AS/400, DBE, e-business logo, ESCO, eServer, FICON, IBM, IBM Logo, iSeries, MVS, OS/390, pSeries, RS/6000, S/30, VM/ESA, VSE/ESA, Websphere, xSeries, z/OS, zSeries, z/VM The following are trademarks or registered trademarks of other companies Lotus, Notes, and Domino are trademarks or registered trademarks of Lotus Development Corporation Java and all Java-related trademarks and logos are trademarks of Sun Microsystems, Inc., in the United States and other countries LINUX is a registered trademark of Linux Torvalds UNIX is a registered trademark of The Open Group in the United States and other countries. Microsoft, Windows and Windows NT are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. SET and Secure Electronic Transaction are trademarks owned by SET Secure Electronic Transaction LLC. Intel is a registered trademark of Intel Corporation * All other products may be trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective companies. -

Annual Report 2011

ANNUAL REPORT 2011 TO OUR STOCKHOLDERS: I am pleased to report that KLA-Tencor performed at record levels on several fronts in fi scal year 2011. We achieved company records in our most critical fi nancial metrics, including revenues, net income, earnings per share and profi t margins, and our year-over-year revenue growth signifi cantly exceeded that of our peer group and our industry. At the same time, we generated record free cash fl ow and continued to deliver meaningful returns to our stockholders in the form of dividends and stock repurchases. This performance was the result of our unwavering focus on develop- ing market-leading technology, addressing our customers’ most critical needs and driving operational effi ciency. Though our industry has seen a recent slowdown in demand, we remain very excited about KLA-Tencor’s prospects for the future. The long-term demand drivers for KLA-Tencor and our industry remain intact, and we are well positioned to grow as demand for semiconductor capital equipment recovers. Our record results in fi scal year 2011 demonstrate that our strategies are working. Looking back over our 35-year history, we have established a pattern of achievement and leadership, which has enabled us to create the strong foundation from which we now look ahead to the future. Our accomplishments during fi scal year 2011 in each of our four strategic objectives (Customer Focus, Growth, Operational Excellence and Talent Development) are highlighted below: CUSTOMER FOCUS: MARKET LEADERSHIP Our customer focus strategic objective is measured in customer satisfaction and market share. We maintained our market leadership positions among our foundry and logic customers in fi scal year 2011 and improved our market position in memory, as evidenced by achieving record new order levels across all our end markets during the year. -

IBM Rational Software IBM Rational Software

® IBM Rational Software Development Conference 2008 SDP30: Jazzing Up IT Best Practices from Internal Deployment of IBM Rational Team Concert Doug Weissman – IT Architect, Rational Software [email protected] Cathy Col – Manager, Rational Engineering Services [email protected] © 2007 IBM Corporation IBM Rational Software Development Conference 2008 Agenda Goal of presentation Why did we centralize deployment of Rational Team Concert? A Simple RTC Configuration Considerations for deploying Rational Team Concert Rational Software’s RTC Deployment Benefits, Best Practices, and Lessons Learned SDP30 – Jazzing Up IT 2 IBM Rational Software Development Conference 2008 Goal of Presentation Help you think about how to deploy Rational Team Concert Give you some suggestions as to possible architectures and configurations Discuss some benefits, best practices, pitfalls, and lessons learned SDP30 – Jazzing Up IT 3 IBM Rational Software Development Conference 2008 Agenda Goal of presentation Why did we centralize deployment of Rational Team Concert? A Simple RTC Configuration Considerations for deploying Rational Team Concert Rational Software’s RTC Deployment Benefits, Best Practices, and Lessons Learned SDP30 – Jazzing Up IT 4 s ent rem qui r re rve l se ima Min IBM Rational Software Development Conference 2008 e Grassroot movement to adopt new technology s u e d bl n si “Jazz” adoptiona was rampant ats Rational! ce d y ac e lo ly s p ee a e fr -b d ad ” o lo ne t n g y ow pa s D rt m a o a E p ch p n dly u w frien e s r o , team -

Getting Started with Rational DOORS Release 9.2 Before Using This Information, Be Sure to Read the General Information Under the "Notices" Chapter on Page 27

IBM Rational DOORS Getting Started with Rational DOORS Release 9.2 Before using this information, be sure to read the general information under the "Notices" chapter on page 27. This edition applies to IBM Rational DOORS, VERSION 9.2, and to all subsequent releases and modifications until otherwise indicated in new editions. © Copyright IBM Corporation 1993, 2010 US Government Users Restricted Rights—Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Table of contents Chapter 1: About this manual 1 Typographical Conventions. 1 Related Documentation . 1 Chapter 2: Introducing Rational DOORS 3 About Rational DOORS . 3 About requirements . 4 About modules. 4 About objects and attributes . 5 Object Heading and Object Text attributes. 6 About traceability . 6 About views . 7 About folders and projects . 7 About tracking changes . 8 About baselines . 9 About edit modes. 9 About the Change Proposal System . 10 About partitions . 11 About user types . 11 About discussions . 12 Chapter 3: Quick tour 13 About this tour. 13 Getting ready to start the tour. 13 Install and run the Example Database . 13 Editing a module . 15 Changing your view . 17 Making a link . 18 Creating an attribute. 20 Sorting and filtering the data . 21 Getting Started with Rational DOORS iii Table of contents Finishing the tour . 21 Chapter 4: Contacting support 23 Contacting IBM Rational Software Support . 23 Prerequisites . 23 Submitting problems. 24 Other information. 26 Chapter 5: Notices 27 Trademarks . 29 Index 31 iv Getting Started with Rational DOORS 1 About this manual Welcome to IBM® Rational® DOORS® 9.2, the world’s leading requirements management application. -

A Model Driven Approach for Service Based System Design Using Interaction Templates

Toni Reichelt A Model Driven Approach for Service Based System Design Using Interaction Templates Wissenschaftliche Schriftenreihe EINGEBETTETE, SELBSTORGANISIERENDE SYSTEME Band 10 Prof. Dr. Wolfram Hardt (Hrsg.) Toni Reichelt A Model Driven Approach for Service Based System Design Using Interaction Templates Chemnitz University Press 2012 Impressum Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Angaben sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Zugl.: Chemnitz, Techn. Univ., Diss., 2012 Technische Universität Chemnitz/Universitätsbibliothek Universitätsverlag Chemnitz 09107 Chemnitz http://www.bibliothek.tu-chemnitz.de/UniVerlag/ Herstellung und Auslieferung Verlagshaus Monsenstein und Vannerdat OHG Am Hawerkamp 31 48155 Münster http://www.mv-verlag.de ISBN 978-3-941003-60-6 URL: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:ch1-qucosa-85986 Preface to the scientific series “Eingebettete, selbstorganisierende Systeme” The tenth volume of the scientific series Eingebettete, selbstorganisierende Systeme (Em- bedded, self-organised systems) devotes itself to the model driven design of service-oriented systems. Fields of application for such systems, amongst others, range from large scale, distributed enterprise solutions down to modularised embedded systems. The presented work was moti- vated by the complex design process of avionics for unmanned systems, where the increased demand for enhanced system autonomy implies high levels of system collaboration and infor- mation exchange. For such system designs a clear separation between the application logic implemented by system components, the means of interaction between them and finally the realisation of such communication on target platforms is essential. In particular, this sep- aration leads to simplification of the complex design processes and increases the individual components’ re-use potential. -

Hello World: Rational Software Architect Design a Simple Phone Book Application

Hello World: Rational Software Architect Design a simple phone book application Skill Level: Introductory Tinny Ng ([email protected]) Advisory Software Developer IBM Toronto 05 May 2006 Welcome to the first tutorial in the "Hello, World! Series", which will provide high-level overviews of various IBM software products. This tutorial introduces you to IBM Rational Software Architect, and highlights some basic features of Rational Software Architect with a hands-on exercise. Learn how to design an application using UML diagrams, publish the model information into a Web page, and transform the design to Java code using Rational Software Architect. Section 1. Before you start About this series This series is for novices who want high-level overviews of various IBM software products. The modules are designed to introduce the products, and draw your interest for further exploration. The exercises only cover the basic concepts, but are enough to get you started. About this tutorial This tutorial provides a high level overview of Rational® Software Architect, and shows some basic features of Rational Software Architect with a hands-on exercise. The exercise has step-by-step instructions for designing an application using UML diagrams, publishing the model information into a Web page, and transforming the design to Java™ using Rational Software Architect. Rational Software Architect © Copyright IBM Corporation 1994, 2008. All rights reserved. Page 1 of 23 developerWorks® ibm.com/developerWorks Prerequisites This tutorial is for application designers at a beginning level, but you should have a general familiarity with using the Eclipse development environment. To run the examples in this tutorial, you need to install IBM Rational Software Architect v6.0. -

Patterns: Model-Driven Development Using IBM Rational Software Architect

Front cover Patterns: Model-Driven Development Using IBM Rational Software Architect Learn how to automate pattern-driven development Build a model-driven development framework Follow a service-oriented architecture case study Peter Swithinbank Mandy Chessell Tracy Gardner Catherine Griffin Jessica Man Helen Wylie Larry Yusuf ibm.com/redbooks International Technical Support Organization Patterns: Model-Driven Development Using IBM Rational Software Architect December 2005 SG24-7105-00 Note: Before using this information and the product it supports, read the information in “Notices” on page ix. First Edition (December 2005) This edition applies to Version 6.0.0.1 of Rational Software Architect (product number 5724-I70). © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 2005. All rights reserved. Note to U.S. Government Users Restricted Rights -- Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents Notices . ix Trademarks . x Preface . xi For solution architects . xi For project planners or project managers . xii For those working on a project that uses model-driven development . xii How this book is organized . xiii The team that wrote this redbook. xiv Become a published author . xv Comments welcome. xvi Part 1. Approach . 1 Chapter 1. Overview and concepts of model-driven development. 3 1.1 Current business environment and drivers . 4 1.2 A model-driven approach to software development . 5 1.2.1 Models as sketches and blueprints . 6 1.2.2 Precise models enable automation . 6 1.2.3 The role of patterns in model-driven development . 7 1.2.4 Not just code . 7 1.3 Benefits of model-driven development . -

9768: Using RTC's ISPF Client for Z/OS Code Development

® IBM Software Group 9768: Using RTC's ISPF Client for z/OS Code Development Rosalind Radcliffe Chief Architect for Jazz for System z and Power Systems Liam Doherty RTC and SCLM Architect Innovation for a smarter planet © 2011 IBM Corporation 1 IBM Software Group | Rational software Rational Team Concert Rational Team Concert brings together diverse teams allowing them to work Collaboration together to c build solutions Collaborate in Context Available Today Right-size Governance Clarity Rational Team Concert Day One Productivity Continuity Open and Extensible Community Architecture JAZZ TEAM SERVER Client Integrations Extensions for System z Eclipse and Eclipse- Native z/OS build support based products Integration with Rational Developer for System z Web 2.0 Integrated SCM solution for z/OS and distributed assets Visual Studio ISPF Flexible Deployment Platforms - z/OS, Linux on System z, or distributed *Statements on future direction subject to change Innovation for a smarter planet 2 IBM Software Group | Rational software What’s new in RTC 3.0.1? •Native z/OS development • ISPF ‘Green Screen’ SCM client •Enterprise Platforms enhancements • Dependency based Build (z/OS) Driving Business Differentiation • Promotion of builds (z/OS) • Deployment of Applications (all platforms except Windows) • Context aware-search Innovation for a smarter planet 3 IBM Software Group | Rational software ISPF ‘Green Screen’ Client Full Function SCM Client ISPF SCM Client • Users can check out/check in code to native z/OS file system • Providing value add -

Les Géants Du Numérique (2) : Un Frein À L’Innovation ?

Paul-Adrien HYPPOLITE Antoine MICHON LES GÉANTS DU NUMÉRIQUE (2) : UN FREIN À L’INNOVATION ? Novembre 2018 fondapol.org LES GÉANTS DU NUMÉRIQUE (2) : UN FREIN À L’INNOVATION ? Paul-Adrien HYPPOLITE Antoine MICHON La Fondation pour l’innovation politique est un think tank libéral, progressiste et européen. Président : Nicolas Bazire Vice Président : Grégoire Chertok Directeur général : Dominique Reynié Président du Conseil scientifique et d’évaluation : Christophe de Voogd 4 FONDATION POUR L’INNOVATION POLITIQUE Un think tank libéral, progressiste et européen La Fondation pour l’innovation politique offre un espace indépendant d’expertise, de réflexion et d’échange tourné vers la production et la diffusion d’idées et de propositions. Elle contribue au pluralisme de la pensée et au renouvellement du débat public dans une perspective libérale, progressiste et européenne. Dans ses travaux, la Fondation privilégie quatre enjeux : la croissance économique, l’écologie, les valeurs et le numérique. Le site fondapol.org met à disposition du public la totalité de ses travaux. La plateforme « Data.fondapol » rend accessibles et utilisables par tous les données collectées lors de ses différentes enquêtes et en plusieurs langues, lorsqu’il s’agit d’enquêtes internationales. De même, dans la ligne éditoriale de la Fondation, le média « Anthropotechnie » entend explorer les nouveaux territoires ouverts par l’amélioration humaine, le clonage reproductif, l’hybridation homme/ machine, l’ingénierie génétique et les manipulations germinales. Il contribue à la réflexion et au débat sur le transhumanisme. « Anthropotechnie » propose des articles traitant des enjeux éthiques, philosophiques et politiques que pose l’expansion des innovations technologiques dans le domaine de l’amélioration du corps et des capacités humaines. -

IBM ® Rational ® Rapid Developer Technical Overview

A Technical Discussion of Rational Rapid Developer Technical Overview July, 2003 IBM® Rational® Rapid Developer Technical Overview James R. Farrell [email protected] Executive Summary The Internet has brought a major revolution in business and technology. It provides the ubiquitous business dial tone that has the potential to automate and transform every aspect of business. Businesses are connected on a real- time basis with customers, vendors, partners and employees. Every aspect of your business is likely to change including business models, types of products and services offered, pricing models, and business relationships. A parallel change is occurring on the technology side. Your applications use n-tier deployment architectures to achieve 24 x 7 availability, and need to be highly scalable and secure. The technology to power your applications is likely to keep changing rapidly. This has an obvious impact on your application development environment. As an application developer you need to anticipate a changing environment in which business and technology become more complex. The vital business processes of today’s organizations increasingly depend on software. Organizations must be able to adapt their software assets rapidly to meet challenges and opportunities as they come along. The ability to generate reliable, scalable business applications has a direct correlation with the ability to respond to both internal and external customer demands. For many organizations, business applications are the most critical software assets, because they reflect the core competency of an organization and are essential for maintaining a competitive edge. Today’s smart organizations are connecting business applications to their customers, vendors, and other partners; they’re connecting the many departments, locations, and people within the enterprise; and they’re making the growing enterprise responsive to the needs of the business.