Cooper's Hill to Windsor-Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Full Book

Respectable Folly Garrett, Clarke Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Garrett, Clarke. Respectable Folly: Millenarians and the French Revolution in France and England. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.67841. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/67841 [ Access provided at 2 Oct 2021 03:07 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. HOPKINS OPEN PUBLISHING ENCORE EDITIONS Clarke Garrett Respectable Folly Millenarians and the French Revolution in France and England Open access edition supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. © 2019 Johns Hopkins University Press Published 2019 Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. CC BY-NC-ND ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3177-2 (open access) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3177-7 (open access) ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3175-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3175-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3176-5 (electronic) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3176-9 (electronic) This page supersedes the copyright page included in the original publication of this work. Respectable Folly RESPECTABLE FOLLY M illenarians and the French Revolution in France and England 4- Clarke Garrett The Johns Hopkins University Press BALTIMORE & LONDON This book has been brought to publication with the generous assistance of the Andrew W. -

The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D.," Appeared in 1791

•Y»] Y Y T 'Y Y Y Qtis>\% Wn^. ECLECTIC ENGLISH CLASSICS THE LIFE OF SAMUEL JOHNSON BY LORD MACAULAY . * - NEW YORK •:• CINCINNATI •:• CHICAGO AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY Copvrigh' ',5, by American Book Company LIFE OF JOHNSOK. W. P. 2 n INTRODUCTION. Thomas Babington Macaulay, the most popular essayist of his time, was born at Leicestershire, Eng., in 1800. His father, of was a Zachary Macaulay, a friend and coworker Wilberforc^e, man "> f austere character, who was greatly shocked at his son's fondness ">r worldly literature. Macaulay's mother, however, ( encouraged his reading, and did much to foster m*? -erary tastes. " From the time that he was three," says Trevelyan in his stand- " read for the most r_ ard biography, Macaulay incessantly, part CO and a £2 lying on the rug before the fire, with his book on the ground piece of bread and butter in his hand." He early showed marks ^ of uncommon genius. When he was only seven, he took it into " —i his head to write a Compendium of Universal History." He could remember almost the exact phraseology of the books he " " rea'd, and had Scott's Marmion almost entirely by heart. His omnivorous reading and extraordinary memory bore ample fruit in the richness of allusion and brilliancy of illustration that marked " the literary style of his mature years. He could have written Sir " Charles Grandison from memory, and in 1849 he could repeat " more than half of Paradise Lost." In 1 81 8 Macaulay entered Trinity College, Cambridge. Here he in classics and but he had an invincible won prizes English ; distaste for mathematics. -

Tennyson's Poems

Tennyson’s Poems New Textual Parallels R. H. WINNICK To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. TENNYSON’S POEMS: NEW TEXTUAL PARALLELS Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels R. H. Winnick https://www.openbookpublishers.com Copyright © 2019 by R. H. Winnick This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work provided that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way which suggests that the author endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: R. H. Winnick, Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2019. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0161 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944#resources Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. -

Milton, Anna Letitia Barbauld, and Anne Grant in the Eighteen Hundreds Justin Stevenson

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Summer 2015 Sin, History, and Liberty: Milton, Anna Letitia Barbauld, and Anne Grant in the Eighteen Hundreds Justin Stevenson Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Stevenson, J. (2015). Sin, History, and Liberty: Milton, Anna Letitia Barbauld, and Anne Grant in the Eighteen Hundreds (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1238 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SIN, HISTORY, AND LIBERTY: MILTON, ANNA LETITIA BARBAULD, AND ANNE GRANT IN THE EIGHTEEN HUNDREDS A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Justin J. Stevenson August 2015 Copyright by Justin J. Stevenson 2015 ii SIN, HISTORY, AND LIBERTY: MILTON, ANNA LETITIA BARBAULD, AND ANNE GRANT IN THE EIGHTEEN HUNDREDS By Justin J. Stevenson Approved July 14, 2015 ________________________________________ Susan K. Howard, Ph.D. Associate Professor of English (Committee Chair) ________________________________________ Laura Engel, Ph.D. Associate Professor of English (Committee Member) ________________________________________ Danielle A. St. Hilaire, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of English (Committee Member) ________________________________________ Greg Barnhisel, Ph.D. Associate Professor of English Chair, English Department ________________________________________ James P. Swindal, Ph.D. Dean, McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts iii ABSTRACT SIN, HISTORY, AND LIBERTY: MILTON, ANNA LETITIA BARBAULD, AND ANNE GRANT IN THE EIGHTEEN HUNDREDS By Justin J. -

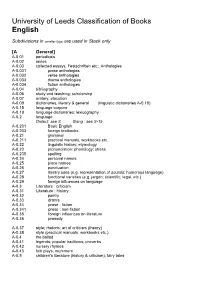

University of Leeds Classification of Books English

University of Leeds Classification of Books English Subdivisions in smaller type are used in Stack only [A General] A-0.01 periodicals A-0.02 series A-0.03 collected essays, Festschriften etc.; Anthologies A-0.031 prose anthologies A-0.032 verse anthologies A-0.033 drama anthologies A-0.034 fiction anthologies A-0.04 bibliography A-0.06 study and teaching; scholarship A-0.07 oratory; elocution A-0.09 dictionaries, literary & general (linguistic dictionaries A-0.19) A-0.15 language corpora A-0.19 language dictionaries; lexicography A-0.2 language Dialect: see S Slang : see S-15 A-0.201 Basic English A-0.203 foreign textbooks A-0.21 grammar A-0.211 practical manuals, workbooks etc. A-0.22 linguistic history; etymology A-0.23 pronunciation; phonology; stress A-0.235 spelling A-0.24 personal names A-0.25 place names A-0.26 punctuation A-0.27 literary uses (e.g. representation of sounds; humorous language) A-0.28 functional varieties (e.g. jargon; scientific, legal, etc.) A-0.29 foreign influences on language A-0.3 Literature : criticism A-0.31 Literature : history A-0.32 poetry A-0.33 drama A-0.34 prose : fiction A-0.341 prose : non-fiction A-0.35 foreign influences on literature A-0.36 prosody A-0.37 style; rhetoric; art of criticism (theory) A-0.38 style (practical manuals, workbooks etc.) A-0.4 the ballad A-0.41 legends; popular traditions; proverbs A-0.42 nursery rhymes A-0.43 folk plays; mummers A-0.5 children’s literature (history & criticism); fairy tales [B Old English] B-0.02 series B-0.03 anthologies of prose and verse Prose anthologies -

The Creative Role of Parody in Eighteenth-Century English Literature

University of Warsaw Institute of English Studies The Creative Role of Parody in Eighteenth-Century English Literature (Alexander Pope, John Gay, Henry Fielding, Laurence Sterne) Przemysław Uściński Doctoral dissertation written under the supervision of Professor Grażyna Bystydzieńska at the Institute of English Studies, University of Warsaw Warszawa 2015 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The present study has been prepared under the supervision and with an invaluable support and encouragement from Professor Grażyna Bystydzieńska from the Institute of English Studies, University of Warsaw. I would like to thank Professor Bystydzieńska in particular for her detailed comments and useful suggestions during the writing of the present study. I am also very grateful for being able to participate in numerous inspiring seminars and conferences organized by Professor Bystydzieńska. I would also like to express my gratitude to different literary scholars and experts in the field of Eighteenth-Century Studies for their helpful comments, suggestions, encouragement and inspiration, in particular to Professor John Barrell from the Queen Mary University of London; Professor Stephen Tapscott from Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Dr. Agnieszka Pantuchowicz from the University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Warsaw; Professor David Malcolm form the University of Gdańsk; Dr. Maria Błaszkiewicz from the University of Warsaw, Professor Adam Potkay from the William and Mary College, Virginia. I wish to warmly thank Professor Emma Harris for encouragement and valuable advice throughout my M.A. and Ph.D. studies at the Institute of English Studies, University of Warsaw. I also want to appreciate the friendly support and insightful remarks I received from all my colleagues at the Ph.D. -

Jonathan Swift and Alexander Pope

Bibliography: 18th Century Satire file:///Macintosh%20HD/Users/kellerw/Documents/Academics/12... Early 18th-Century Satire: Jonathan Swift and Alexander Pope A Bibliography compiled by Wolfram R. Keller Note: Only one editor is named in cases of essay collections with more than two editors. Articles from Dissertation Abstracts International are only listed in case they are especially relevant. Essays from Explicator are not listed. Likewise, Notes and Queries-articles are neglected unless they seem particularly relevant. To save space, I did not mention the series book-length studies have been published in. Finally, in case of special journal issues dealing with seminar-relevant material, articles have been listed separately to allow for a better overview in terms of inter-library loans. Also, a comprehensive bibliography can be found on the following website "Theorizing Satire: A Bibilography". Please send comments and additions to <[email protected]>. Editions and Bibliographies General Theoretical Works Alexander Pope Jonathan Swift Comparative Studies 1. Editions and Bibliographies Bloom, Harold. Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels. New York: Chelsea, 1986. Cassetta, Richard. "The Rape of the Lock in the 1980s: An Annotated Bibliography." New Orleans Review 15.4 (1988): 78-9. Cowler, Rosemary. The Prose Works of AlexanderPope, Vol. 2: The Major Works, 1725-1744. Hamden, CT: Archon, 1986. Fox, Christopher and Ross C. Murfin, eds. Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels: Complete, Authoritative Text with Biographical and Historical Contexts, Critical History, and Essays from Five Contemporary Critical Perspectives. Boston: Bedford, 1995. Greenberg, Robert and William Piper, eds. Writings of Jonathan Swift. New York: Norton, 1973. -

Swift's Opinions of Contemporary English Literary Figures

Cl SWIFT’S OPINIONS OF CONTEMPORARY ENGLISH LITERARY FIGUHBS Carl Ray Woodring l A Thesis 4 Presented to the Faculty of the Rice Institute, Houston, Texas, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts & V Houston, Texas 1942 V CONTENTS Foreword i Introduction ii I. Moor park 1 II. London 29 III. Londons The Scrlblerus Club 72 IV. Ireland 100 Conclusion 131 Bibliography The present belated trend toward recognizing the validity of Swift’s ideas as well as the power of his art influenced ny choice of Swift as a concentrating point* The immediate subjeot of this thosis was suggested by Professor Alan D* KcKillop, whose general and specific criticisms of the manuscript through all its stages have been of inestimable and elsewhere unacknowledged value* Although it will be evident presently that the debts are greater than the accomplishment, I should like to name here, besides Professor MoKillop, MM* George G* Williams, Joseph D* Thomas, Carroll Camden, Joseph V/* Hendren, and George W* Whiting, of the Faculty of English, and Floyd S* Lear, of the Faoulty of History, not so much for lectures, which provided general background and methods of approaoh, as for their courtesy in answering sporadic questions concerning details of the present paper* Acknowledgments of debt to printed sources have been rendered, except for general information, in the foot¬ notes* The Bibliography printed at the end of the text is not a complete bibliography of Swiftian and related volumes, or even of books examined, but a finding-list -

“Monuments of Unageing Intellect”

“Monuments of Unageing Intellect” by Melvyn New Which one of us would not dream that it might be said of his work of a lifetime: “He wrote a few good footnotes”? Simon Leys, The Hall of Uselessness. Several years ago Janine Barchas wrote an review essay of the first three volumes of the Cambridge Edition of the Works of Samuel Richardson (Eighteenth-Century Life, 38.3 [2014], 118-24), entitled “First and Last,” a title reflecting the fact that the Cambridge Works will be “the first-ever annotated edition of this author’s complete output” (my italics) and her opinion that it will be the last such print edition. Perhaps this caught my attention because in the same year I had just published the ninth and final volume of my thirty-five-year project of a scholarly edition of Laurence Sterne’s works, and had opined in its introduction that “what a scholarly editor learns, and I believe my coeditors will agree with this, is that after the final volume of the Florida Sterne, nothing remains but to start over again. A new scholarly edition of Sterne’s works will perhaps not be undertaken for another decade or two, but if Sterne is to continue to be read, his work must be edited and annotated anew for different times and new readers.” Or, just as likely, her review caught my eye because I am a coeditor of four volumes in the Richardson project, a scholarly edition of Sir Charles Grandison. Whatever the reason, I found her essay-review captivating, if also disturbing, and was even temporarily persuaded by many of her cogent arguments against the seemingly endless proliferation of very costly scholarly editions in the electronic era. -

Alexander Pope 1 Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope 1 Alexander Pope Alexander Pope Alexander Pope (c. 1727), an English poet best known for his Essay on Criticism, The Rape of the Lock and The Dunciad Born 21 May 1688 London Died 30 May 1744 (aged 56) Twickenham (today an incorporated area of London) Occupation Poet Signature Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 – 30 May 1744) was an 18th-century English poet, best known for his satirical verse and for his translation of Homer. Famous for his use of the heroic couplet, he is the third-most frequently quoted writer in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, after Shakespeare and Tennyson.[1] Alexander Pope 2 Life Early life Pope was born to Alexander Pope (1646–1717), a linen merchant of Plough Court, Lombard Street, London, and his wife Edith (née Turner) (1643–1733), who were both Catholics.[3] Edith's sister Christiana was the wife of the famous miniature painter Samuel Cooper. Pope's education was affected by the recently enacted Test Acts, which upheld the status of the established Church of England and banned Catholics from teaching, attending a university, voting, or holding public office on pain of perpetual imprisonment. Pope was taught to read by his aunt, and went to Twyford School in about 1698/99.[3] He then went to two Catholic schools in London.[3] Such schools, while illegal, were tolerated in some areas.[4] A likeness of Pope derived from a portrait by [2] In 1700, his family moved to a small estate at Popeswood in Binfield, William Hoare Berkshire, close to the royal Windsor Forest.[3] This was due to strong anti-Catholic sentiment and a statute preventing Catholics from living within 10 miles (16 km) of either London or Westminster.[5] Pope would later describe the countryside around the house in his poem Windsor Forest. -

American Dissertations on Foreign Education: a Bibliography with Abstracts

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 351 277 SO 022 710 AUTHOR Parker, Franklin, Ed.; Parker, Betty June, Ed. TTTLE American Dissertations on Foreign Education: A Bibliography with Abstracts. Volume XX. Britain: Biographies of Educators; Scholars' Educational Ideas. REPORT NO ISBN-0-87875-341-9 PUB DATE 90 NOTE 461p.; For prior volumes, see ED 308 111. AVAILABLE FROMWhitston Publishing Company, Post Office Box 958, Troy, NY 12181 ($55.00). PUB TYPE Books (010) Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC19 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Biographies; *Doctoral Dissertations; *Educational Research; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *International Education IDENTIFIERS *Great Britain ABSTRACT This book contains 236 abstracts of dissertations that concern the ideas and/or lives of educators and scholars who were born and taught in Great Britain, or who, if not born in Great Britain, did important teaching, writing, and other work there. The dissertations featured were completed at colleges and universities and other educational institutions in the United States, Canada, and some European countries. The abstracts of the dissertations are compiled in alphabetical order by the author's name. An index is included. (DB) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** I r U DEPARTMENT Of EDUCATION °Pc* of Educational Research and Improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER -

Finzi Book Room

THE FINZI BOOK ROOM READING UNIVERSITY LIBRARY PUBLICATIONS 4 THE FINZI BOOK ROOM AT THE UNIVERSITY OF READING THE FINZI BOOK ROOM AT THE UNIVERSITY OF READING A CATALOGUE by Pauline Dingley Introduction by Adrian Caesar THE LIBRARY UN IVERSITY OF READING 198 1 The library University of Reading Whiteknlghts Reading © 1981 The Library, University of Reading ISBN 0 7049 0492 6 Designed by the Libanus Press. Marlborough, Willshire Printed in Great Britain by Sherwood Printers (Mansfield) Limited, Ncttingharnshirc CONTENTS INTRODUCTION BY ADRIAN CAESAR, vii THE A R RAN GEM E NT 0 F THE CAT A LOG U E, xxi ACK NOWLEDGE ME NTS, xxi CATALOGUE GENERAL HISTORIES AND STUDIES, I GENERAL ANTHOLOGIES, 7 (to 1500) THE ANGLO-SAXON AND MIDDLE ENGLISH PERIOD Histories and studies, 15 Anthologies, 15 Individual authors, 17 THE RENAISSANCE TO THE RESTORATION (1500 - 1660) Histories and studies, 19 Anthologies, 20 Individual authors, 22 (1660 - 1800) THE RESTORATION TO THE ROMANTICS Histories and studies, 37 Anthologies, 38 Individual authors, 39 (1800 - 1900) THE NINETEENTH CENTURY Histories and studies, 51 Anthologies, 51 Individual authors, 52 THE TWENTIETH CENTURY (1900 - ) Histories and studies, 77 Anthologies, 77 Individual authors, 79 TRANSLATrONS, 113 IN DEX 0F POE TS,J25 INTRODUCTION GERALDFINZIwas born on the 14th July 1901 the fifth and last born child of a city business- man. By all accounts his arrival into an already crowded nursery was not greeted with enthusiasm. Those who could have been his first companions and friends, his sister and brothers, were strangers to him from the first. Feeling increasingly isolated he turned to a private world of books and music.