Ramleela in Trinidad, 2006–2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Hinduism: a Unit for Junior High and Middle School Social Studies Classes

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 322 075 SO 030 122 AUTHOR Galloway, Louis J. TITLE Hinduism: A Unit for Junior High and Middle School Social Studies Classes. SPONS AGENCY Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC.; United States Educational Fouldation in India. PUB DATE 89 NOTE 12p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE mFol/rcol Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Asian History; Class Activities; Curriculum Design; Epics; Foreign Countries; Foreign Culture; Global Approach; *History Instruction; Instructional Materials; Junior High Schools; *Non Western Civilization; Social Studies; Visual Aids IDENTIFIERS *Hinduism; *India ABSTRACT As an introduction and explanation of the historical development, major concepts, beliefs, practices, and traditions of Hinduism, this teaching unit provides a course outline for class discussion and activities for reading the classic epic, "The Ramayana." The unit requires 10 class sE,sions and utilizes slides, historical readings, class discussions, and filmstrips. Worksheets accompany the reading of this epic which serves as an introduction to Hinduism and some of its major concepts including: (1) karma; (2) dharma; and (3) reincarnation. (NL) ************************************************************t********** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can Le made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** rso Hinduism: A Unit For Junior High and Middle School Social Studies Classes t prepared by Louis J. Galloway CYZ Ladue Junior High School C=1 9701 Conway. Road St. Louis, Mo. 63124 as member of Summer Fulbright Seminar To India, 1988 sponsored by The United States Department of Education and The United States Educational Foundation in India U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and Improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) his document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization originating it. -

How the Designation of the Steelpan As the National Instrument Heightened Identity Relations in Trinidad and Tobago Daina Nathaniel

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Finding an "Equal" Place: How the Designation of the Steelpan as the National Instrument Heightened Identity Relations in Trinidad and Tobago Daina Nathaniel Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION FINDING AN “EQUAL” PLACE: HOW THE DESIGNATION OF THE STEELPAN AS THE NATIONAL INSTRUMENT HEIGHTENED IDENTITY RELATIONS IN TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO By DAINA NATHANIEL A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2006 Copyright © 2006 Daina Nathaniel All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Daina Nathaniel defended on July 20th, 2006. _____________________________ Steve McDowell Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________ Phil Steinberg Outside Committee Member _____________________________ John Mayo Committee Member _____________________________ Danielle Wiese Committee Member Approved: _____________________________________ Steve McDowell, Chair, Department of Communication _____________________________________ John Mayo, Dean, College of Communication The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This project is dedicated to the memory of my late father, Danrod Nathaniel, without whose wisdom, love and support in my formative years, this level of achievement would not have been possible. I know that where you are now you can still rejoice in my accomplishments. R.I.P. 01/11/04 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS “Stand in the space that God has created for you …” It is said that if you do not stand for something, you will fall for anything. -

HINDU GODS and GODDESSES 1. BRAHMA the First Deity of The

HINDU GODS AND GODDESSES 1. BRAHMA The first deity of the Hindu trinity, Lord Brahma is considered to be the god of Creation, including the cosmos and all of its beings. Brahma also symbolizes the mind and intellect since he is the source of all knowledge necessary for the universe. Typically you’ll find Brahma depicted with four faces, which symbolize the completeness of his knowledge, as well as four hands that each represent an aspect of the human personality (mind, intellect, ego and consciousness). 2. VISHNU The second deity of the Hindu trinity, Vishnu is the Preserver (of life). He is believed to sustain life through his adherence to principle, order, righteousness and truth. He also encourages his devotees to show kindness and compassion to all creatures. Vishnu is typically depicted with four arms to represent his omnipotence and omnipresence. It is also common to see Vishnu seated upon a coiled snake, symbolizing the ability to remain at peace in the face of fear or worry. 3. SHIVA The final deity of the Hindu trinity is Shiva, also known as the Destroyer. He is said to protect his followers from greed, lust and anger, as well as the illusion and ignorance that stand in the way of divine enlightenment. However, he is also considered to be responsible for death, destroying in order to bring rebirth and new life. Shiva is often depicted with a serpent around his neck, which represents Kundalini, or life energy. 4. GANESHA One of the most prevalent and best-known deities is Ganesha, easily recognized by his elephant head. -

Agastya Nadi Samhita

CHAPTER NO. 1 Sri. Agastya Naadi Samhita A mind - boggling Miracle In today’s world of science, if just from the impression of your thumb somebody accurately tells you, your name, the names of your mother, father, husband/wife, your birth-date, month, age etc. what would you call such prediction? Would you regard it as an amazing divination or as black magic? No, it is neither black magic nor a hand trick. Such prediction, which defies all logic and boggles one’s mind, forms the subject-matter of the Agastya Naadi. Those predictions were visualised at different places by various ancient Sages, with their divine insight and factually noted by their chosen disciples, thousands of years ago, to be handed down from generation to generation. This great work makes us realize the limitations of human sciences. That great compilation predicting the future of all human beings born or yet to be born, eclipses the achievements of all other sciences put together! Naadi is a collective name given to palm-leaf manuscripts dictated by ancient sages predicting the characteristics, family history, as well as the careers of innumerable individuals. The sages (rishis), who dictated those Naadis, were gifted with such a remarkable foresight – that they accurately foretold the entire future of all mankind. Many scholars in different parts of India have in their safekeepings several granthas (volumes) of those ancient palm-leaf manuscripts dictated by the great visualizing souls, alias sages such as Bhrugu, Vasistha, Agastya, Shukra, and other venerable saints. I had the good-fortune to consult Sri. Agastya Naadi predictions. -

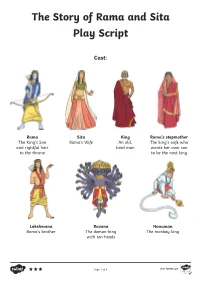

The Story of Rama and Sita Play Script

The Story of Rama and Sita Play Script Cast: Rama Sita King Rama’s stepmother The King’s Son Rama’s Wife An old, The king’s wife who and rightful heir tired man wants her own son to the throne to be the next king Lakshmana Ravana Hanuman Rama’s brother The demon-king The monkey king with ten heads Cast continued: Fawn Monkey Army Narrator 1 Monkey 1 Narrator 2 Monkey 2 Narrator 3 Monkey 3 Narrator 4 Monkey 4 Monkey 5 Prop Ideas: Character Masks Throne Cloak Gold Bracelets Walking Stick Bow and Arrow Diva Lamps (Health and Safety Note-candles should not be used) Audio Ideas: Bird Song Forest Animal Noises Lights up. The palace gardens. Rama and Sita enter the stage. They walk around, talking and laughing as the narrator speaks. Birds can be heard in the background. Once upon a time, there was a great warrior, Prince Rama, who had a beautiful Narrator 1: wife named Sita. Rama and Sita stop walking and stand in the middle of the stage. Sita: (looking up to the sky) What a beautiful day. Rama: (looking at Sita) Nothing compares to your beauty. Sita: (smiling) Come, let’s continue. Rama and Sita continue to walk around the stage, talking and laughing as the narrator continues. Rama was the eldest son of the king. He was a good man and popular with Narrator 1: the people of the land. He would become king one day, however his stepmother wanted her son to inherit the throne instead. Rama’s stepmother enters the stage. -

Kaveri – 2019 Annual Day Script Bala Kanda: Rama

Kaveri – 2019 Annual Day Script Bala Kanda: Rama marries Sita by breaking the bow of Shiva Janaka: I welcome you all to Mithila! As you see in front of you, is the bow of Shiva. Whoever is able to break this bow of Shiva shall wed my daughter Sita. Prince 1: Bows to the crowd and tries to lift the bow and is unsuccessful Prince 2: Bows to the crowd and tries to lift the bow and is unsuccessful Rama 1: Bows, prays to the bow, lifts it, strings it and pulls the string back and bends and breaks it Janaka: By breaking Shiva’s bow, Rama has won the challenge and Sita will be married to Rama the prince of Ayodhya. Ayodhya Kanda: Narrator: Rama, Sita, Lakshmana, Shatrugna, Bharata are all married in Mithila and return to Ayodhya and lived happily for a number of years. Ayodhya rejoiced and flourished under King Dasaratha and the good natured sons of the King. King Dasaratha felt it was time to crown Rama as the future King of Ayodhya. Dasaratha: Rama my dear son, I have decided that you will now become the Yuvaraja of Ayodhya and I would like to advice you on how to rule the kingdom. Rama 2: I will do what you wish O father! Let me get your blessings and mother Kausalya’s blessings. (Rama bows to Dasaratha and goes to Kausalya) Kausalya: Rama, I bless you to rule this kingdom just like your father. Narrator: In the mean time, Manthara, Kaikeyi’s maid hatches out an evil plan. -

Trinidad and Tobago 2017 International Religious Freedom Report

TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO 2017 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution provides for freedom of conscience and religious belief and practice, including worship. It prohibits discrimination based on religion. Laws prohibit actions that incite religious hatred and violence. In June the parliament unanimously passed legislation outlawing childhood marriage, which changed the legal marriage age for all regardless of religious affiliation to 18. The president proclaimed the legislation in September. Religious organizations had mixed reactions to the new law. The Hindu Women’s Organization of Trinidad and Tobago, the National Muslim Women’s Organization of Trinidad and Tobago, and other nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) supported the legislation, while some religious organizations, including the leader of an orthodox Hindu organization (Sanatan Dharma Maha Saba) said it would infringe on religious rights. Religious groups said the government continued its financial support for religious ceremonies and for the Inter-Religious Organization (IRO), an interfaith coordinating committee. The government’s national security policy continued to limit the number of long-term foreign missionaries to 35 per registered religious group at any given time. The government-funded IRO, representing diverse denominations within Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and the Bahai Faith, continued to advocate for matters of religious concern and the importance of religious tolerance. With a mandate “to speak to the nation on matters of social, moral, and spiritual concern,” the IRO focused its efforts on marches, press conferences, and statements regarding tolerance for religious diversity and related issues. U.S. embassy representatives met with senior government officials from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to discuss the importance of government protection of religious equality. -

Religion and the Alter-Nationalist Politics of Diaspora in an Era of Postcolonial Multiculturalism

RELIGION AND THE ALTER-NATIONALIST POLITICS OF DIASPORA IN AN ERA OF POSTCOLONIAL MULTICULTURALISM (chapter six) “There can be no Mother India … no Mother Africa … no Mother England … no Mother China … and no Mother Syria or Mother Lebanon. A nation, like an individual, can have only one Mother. The only Mother we recognize is Mother Trinidad and Tobago, and Mother cannot discriminate between her children. All must be equal in her eyes. And no possible interference can be tolerated by any country outside in our family relations and domestic quarrels, no matter what it has contributed and when to the population that is today the people of Trinidad and Tobago.” - Dr. Eric Williams (1962), in his Conclusion to The History of the People of Trinidad and Tobago, published in conjunction with National Independence in 1962 “Many in the society, fearful of taking the logical step of seeking to create a culture out of the best of our ancestral cultures, have advocated rather that we forget that ancestral root and create something entirely new. But that is impossible since we all came here firmly rooted in the cultures from which we derive. And to simply say that there must be no Mother India or no Mother Africa is to show a sad lack of understanding of what cultural evolution is all about.” - Dr. Brinsley Samaroo (Express Newspaper, 18 October 1987), in the wake of victory of the National Alliance for Reconstruction in December 1986, after thirty years of governance by the People’s National Movement of Eric Williams Having documented and analyzed the maritime colonial transfer and “glocal” transculturation of subaltern African and Hindu spiritisms in the southern Caribbean (see Robertson 1995 on “glocalization”), this chapter now turns to the question of why each tradition has undergone an inverse political trajectory in the postcolonial era. -

Sita Ram Baba

सीता राम बाबा Sītā Rāma Bābā סִיטָ ה רְ אַמָ ה בָבָ ה Bābā بَابَا He had a crippled leg and was on crutches. He tried to speak to us in broken English. His name was Sita Ram Baba. He sat there with his begging bowl in hand. Unlike most Sadhus, he had very high self- esteem. His eyes lit up when we bought him some ice-cream, he really enjoyed it. He stayed with us most of that evening. I videotaped the whole scene. Churchill, Pola (2007-11-14). Eternal Breath : A Biography of Leonard Orr Founder of Rebirthing Breathwork (Kindle Locations 4961-4964). Trafford. Kindle Edition. … immortal Sita Ram Baba. Churchill, Pola (2007-11-14). Eternal Breath : A Biography of Leonard Orr Founder of Rebirthing Breathwork (Kindle Location 5039). Trafford. Kindle Edition. Breaking the Death Habit: The Science of Everlasting Life by Leonard Orr (page 56) ראמה راما Ράμα ראמה راما Ράμα Rama has its origins in the Sanskrit language. It is used largely in Hebrew and Indian. It is derived literally from the word rama which is of the meaning 'pleasing'. http://www.babynamespedia.com/meaning/Rama/f Rama For other uses, see Rama (disambiguation). “Râm” redirects here. It is not to be confused with Ram (disambiguation). Rama (/ˈrɑːmə/;[1] Sanskrit: राम Rāma) is the seventh avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu,[2] and a king of Ayodhya in Hindu scriptures. Rama is also the protagonist of the Hindu epic Ramayana, which narrates his supremacy. Rama is one of the many popular figures and deities in Hinduism, specifically Vaishnavism and Vaishnava reli- gious scriptures in South and Southeast Asia.[3] Along with Krishna, Rama is considered to be one of the most important avatars of Vishnu. -

Sagar Shiv Mandir

Sagar Shiv Mandir Sagar Shiv Mandir, Mauritius. Take a look at this place in Mauritius through the eyes of tourists. View View View View View View View View. Share your visit experience about Sagar Shiv Mandir, Mauritius and rate it: Details. coordinates Sagar Shiv Mandir is on the eastern part of Mauritius. It is a place of worship for Hindus settled in Mauritius and it is also visited by tourists. The temple was constructed in 2007 and it hosts a 108 feet height bronze coloured statue of Shiva. On every maha shivratri day at least 3 lakh people throng this place to pay their respect to the temple of Lord shiva . also next to it another statue of Ma Durga is being constructed. The temple is on bank of Ganga talao, which was supposed to be the creation of Lord shiva. Sagar Shiv Mandir is a hindu temple sitting on the island of Goyave de Chine, Mauritius territory. It is a place of worship for many hindus around the world and. vics12.wix.com. album. Album Sept 2012. Sagar Shiv Mandir Mauritius added 19 new photos to the album Sept 2012. · 3 September 2012 ·. Sept 2012 - after abhishek. Sept 2012. 19 photos. Sagar Shiv Mandir Mauritius. · 24 July 2012 ·. http://youtu.be/Y9Jstt8iXFs. Sagar Shiv Mandir - 3.1. Hindu Temple on sea, Poste de Flacq, Mauritius. youtube.com. Sagar Shiv Mandir is a Hindu temple sitting on the island of Goyave de Chine, Poste de Flacq, Mauritius. Sagar Shiv Mandir is on the eastern part of Mauritius. -

9 Ever Remember the Name of Rama

103 9 Ever Remember The Name Of Rama HOUSANDS of years have passed since the Tadvent of Treta Yuga, yet even now everyone, right from children to elderly people, remember the name of Rama. The glory of Rama’s name is such that it has not diminished even a bit with the passage of time. This truth should be recognised by all. Rama is the name given to a form, but the name of Rama is not limited to a form. Atma is Rama, and its true name is Atmarama. Therefore, wherever and whenever you remember the name of Rama, Rama is there with you, in you, around you. The Name Of Rama Is Eternal Embodiments of Love! Rama is one, whether you identify him with the 104 SATHYA SAI SPEAKS, Volume 40 atma or with the form installed in your heart. Every year comes the festival of Sri Rama Navami. But we have not so far understood its true significance. You identify Rama with a form. But Rama is not limited to any particular form. It is the name that is latent in your heart. Many changes and variations keep occurring in the world, but the name of Rama is immutable, eternal, unsullied and everlasting. Rama was not an ordinary individual. He was verily God who incarnated on earth for the welfare of mankind. People call God by many names like Rama, Krishna, Easwara and Mahadeva. They are all the names of one God. You should recognise the glory of this name. Sage Vasishta said, “Ramo vigrahavan Dharma” (Rama is the personification of Dharma).