Formal Opinion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethics 2000 Committee Members

ETHICS 2000 COMMITTEE MEMBERS Chair Robert I. Cusick [July 2003 – March 2006] 1201 New York Avenue Suite 500 Washington, DC 202-482-9292 [email protected] Chair Dulaney L. O’Roark [March 2006 Forward] 914 Albemarle Court Louisville, KY 40222 502-429-6457 [email protected] John T. Ballantine 2000 PNC Plaza 500 West Jefferson Street, Suite 2000 Louisville, KY 40202 502-582-1601 [email protected] Professor Edward C. Brewer Northern Kentucky University NH 556 Nunn Drive Highland Heights, KY 41099 859-572-6943 [email protected] Donald H. Combs Post Office Drawer 31 Pikeville, KY 41502-0031 606-437-6226 [email protected] Jane Winkler Dyche 402 W. Fifth St. Post Office Box 5156 London, KY 40745 606-877-2991 [email protected] Linda S. Ewald University of Louisville Law School Belknap Campus Louisville, KY 40292 502-852-7362 [email protected] D. Scott Furkin Administrative Office of the Courts 100 Millcreek Park Frankfort, KY 40601 502-573-2350 [email protected] Sheldon G. Gilman Lynch, Cox, Gilman & Mahan, PSC 500 W Jefferson Street, Suite 2100 Louisville, KY 40202 502-589-4215 [email protected] Linda A. Gosnell Kentucky Bar Association 514 West Main Street Frankfort, KY 40601 502-564-3795 [email protected] Jane E. Graham 401 W. Main St., Ste 314 Lexington, KY 40507 859-266-4092 [email protected] Janet Jakubowicz 3300 National City Tower 101 South 5th Street Louisville, KY 40202 502-589-4200 [email protected] William E. Johnson 326 West Main Street Frankfort, KY 40601 502-875-6000 [email protected] Justice John D. -

KBA President J. Stephen Smith and Vicki Prichard at Home in Ft. Mitchell

JULY/AUGUST 2019 KBA President J. Stephen Smith and Vicki Prichard at home in Ft. Mitchell Individual Own Occupation Disability Coverage for Kentucky Attorneys Affordable KBA Rates from Metlife KBA Member Semiannual Rates Monthly Coverage Amount: $3,000 $5,000 $10,000 Under 30 yrs $152 $252 $502 30-39 yrs $213 $354 $705 40-49 yrs $352 $585 $1,167 ✓ No Medical Exam (Under Age 50) ✓ No Tax Returns ✓ Apply for up to $10,000/month Coverage ✓ Residual Disability Coverage ✓ Industry Standard Disability Definition ✓ Easy Online Application Visit www.NIAI.com/Attorneys for KBA quotes and application Call or Email TODAY | 800.928.6421 | [email protected] | www.NIAI.com This issue of the Kentucky Bar Association’s VOL. 83, NO. 4 B&B-Bench & Bar was published in the month of July. COMMUNICATIONS & PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Contents James P. Dady, Chair, Bellevue 2 President’s Page Paul Alley, Florence By: J. Stephen Smith Elizabeth M. Bass, Gallatin, Tenn. Rhonda J. Blackburn, Pikeville 5 Q&A with KBA President J. Stephen Smith Jenn L. Brinkley, Pensacola, Fla. 8 2019 KBA Annual Convention Wrap Up Frances E. Catron Cadle, Lexington Anne A. Chesnut, Lexington Features: Legislative Update Elizabeth A. Deener, Lexington Tamara A. Fagley, Lexington 18 Kentucky, Hemp, and the Law Cathy W. Franck, Crestwood By: Ryan Quarles, Kentucky Commissioner of Agriculture Lonita Baker Gaines, Louisville 22 Legislative Update on Abortion Access in Kentucky William R. Garmer, Lexington By: Jennifer L. Brinkley P. Franklin Heaberlin, Prestonsburg Judith B. Hoge, Louisville 26 Open Courts: Section 14 of the Kentucky Constitution Jessica R. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Nationally, approximately 40% of new attorneys work at firms consisting of more than 50 lawyers. Therefore, a large percentage of practicing attorneys work for small firms (fewer than 50 attorneys). Small firms generally do not have formalized recruiting procedures or a set “hiring season” when they recruit summer law clerks, school-year law clerks, or entry-level attorneys. Instead, these firms hire on an as-needed basis, and they hire year round. To secure employment with a small firm, students and lawyers alike need to be proactive in getting their name and interests out in the community. Applicants should not only apply directly to these firms, but they should connect via law school, community, and bar association activities. In this directory, you will find state-by-state hyperlinks to regional directories, bar associations, newspapers, and job banks that can be used to jump-start a small firm search. ALABAMA State/Regional Bar Associations Alabama Bar Association: http://www.alabar.org Birmingham Bar Association: http://www.birminghambar.org Mobile Bar Association: http://www.mobilebar.org Specialty Bar Associations Alabama Defense Lawyers Association: http://www.adla.org Alabama Trial Lawyers Association: http://www.alabamajustice.org Major Newspapers Birmingham News: http://www.al.com/birmingham Mobile Register: http://www.al.com/mobile Legal & Non-Legal Resources & Publications State Lawyers.com: http://alabama.statelawyers.com EINNEWS: http://www.einnews.com/alabama Birmingham Business Journal: http://birmingham.bizjournals.com -

US Guide to Bar Admission Requirements, 2016

Comprehensive Guide to Bar Admission Requirements 2016 NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BAR EXAMINERS AND AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION SECTION OF LEGAL EDUCATION AND ADMISSIONS TO THE BAR National Conference of Bar Examiners Comprehensive Guide to Bar Admission Requirements 2016 NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BAR EXAMINERS AND AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION SECTION OF LEGAL EDUCATION AND ADMISSIONS TO THE BAR National Conference of Bar Examiners EDITORS ERICA MOESER CLAIRE J. GUBACK This publication represents the joint work product of the National Conference of Bar Examiners and the ABA Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar. The views expressed herein have not been approved by the House of Delegates or the Board of Governors of the American Bar Association, nor has such approval been sought. Accordingly, these materials should not be construed as representing the policy of the American Bar Association. National Conference of Bar Examiners 302 South Bedford Street, Madison, WI 53703-3622 608-280-8550 • TDD 608-661-1275 • Fax 608-280-8552 www.ncbex.org Chair: Hon. Thomas J. Bice, Fort Dodge, IA President: Erica Moeser, Madison, WI Immediate Past Chair: Bryan R. Williams, New York, NY Chair-Elect: Robert A. Chong, Honolulu, HI Secretary: Hon. Rebecca White Berch, Phoenix, AZ Board of Trustees: Hulett H. Askew, Atlanta, GA Patrick R. Dixon, Newport Beach, CA Michele A. Gavagni, Tallahassee, FL Gordon J. MacDonald, Manchester, NH Hon. Cynthia L. Martin, Kansas City, MO Suzanne K. Richards, Columbus, OH Hon. Phyllis D. Thompson, Washington, DC Timothy Y. Wong, St. Paul, MN ABA House of Delegates Representative: Hulett H. Askew, Atlanta, GA American Bar Association Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar 321 North Clark Street, Chicago, IL 60654-7598 312-988-6738 • Fax 312-988-5681 www.americanbar.org/legaled Chair: Hon. -

In the District Court of the Virgin Islands Division of St

Case: 3:11-cv-00078-CVG-RM Document #: 200 Filed: 10/31/11 Page 1 of 10 IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE VIRGIN ISLANDS DIVISION OF ST. THOMAS AND ST. JOHN POLICE BENEVOLENT ASSOCIATION, LOCAL 1910, ET AL., CASE NO. 2011B78 Plaintiffs, v. GOVERNMENT OF THE VIRGIN ISLANDS, ET AL., Defendants. ST. CROIX FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, LOCAL 1826, ET AL., CASE NO. 2011B79 Plaintiffs, v. GOVERNMENT OF THE VIRGIN ISLANDS, ET AL., Defendants. UNITED STEEL, PAPER & FORESTRY, RUBBER, MANUFACTURING, ET AL., CASE NO. 2011B76 Plaintiffs, v. GOVERNMENT OF THE VIRGIN ISLANDS, ET AL., Defendants. Case: 3:11-cv-00078-CVG-RM Document #: 200 Filed: 10/31/11 Page 2 of 10 Lead Case: Police Ben. Ass=n, et al. v. GVI, et al. Civil No. 2011-78 Memorandum and Order Page 2 AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, LOCAL 1825, ET AL., CASE NO. 2011B77 Plaintiffs, v. GOVERNMENT OF THE VIRGIN ISLANDS, ET AL., Defendants. INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF FIREFIGHTERS LOCAL 2125, ET AL., CASE NO. 2011B81 Plaintiffs, v. GOVERNMENT OF THE VIRGIN ISLANDS, ET AL., Defendants. MEMORANDUM AND ORDER Before the Court is the Legislature of the Virgin Islands= motion to disqualify Nizar A. DeWood, Esq., as counsel for plaintiffs Police Benevolent Association (Local 1910, St. Croix Chapter), Law Enforcement Supervisors Union (Local 119, St. Croix Chapter), Arthur A. Joseph, Sr. and Freddy Ortiz, Jr. (collectively, the “PBA/LESU”). The Legislature contends that disqualification is appropriate because Attorney DeWood wrongfully communicated with members of the Legislature in violation of Rule 4.2 of the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct. Plaintiffs opposes the motion, arguing that any contacts that occurred were prior to the initiation of the lawsuit and therefore outside the scope of Rule 4.2, or were otherwise authorized pursuant to Rule 4.2. -

Materials Included in This Diversity and Inclusion Summit Seminar Book Are Intended to Provide Current and Accurate Information About the Subject Matter Covered

CLE Credit: 6.0 Friday, March 22, 2019 Northern Kentucky Convention Center Covington, Kentucky ©2019 by the Kentucky Bar Association Continuing Legal Education Commission Lori J. Alvey, Sonja M. Blackburn, Caroline J. Carter, Mary E. Cutter, and EmaLeigh C. Haines, Editors All rights reserved Published March 2019 Editor’s Note: The materials included in this Diversity and Inclusion Summit seminar book are intended to provide current and accurate information about the subject matter covered. The program materials were compiled for you by volunteer authors and from national legal publications. No representation or warranty is made concerning the application of the legal or other principles discussed by the instructors to any specific fact situation, nor is any prediction made concerning how any particular judge or jury will interpret or apply such principles. The proper interpretation or application of the principles discussed is a matter for the considered judgment of the individual legal practitioner. The faculty and staff of the Diversity and Inclusion Summit disclaim liability therefor. Attorneys using these materials or information otherwise conveyed during the program, in dealing with a specific legal matter, have a duty to research original and current sources of authority. The Kentucky Bar Association would like to give special thanks to the volunteer authors who contributed to this program handbook. Printed by: Kentucky Bar Association 514 West Main Street Frankfort, Kentucky 40601 TABLE OF CONTENTS Program Agenda .......................................................................................................... -

Kentucky Bar Association New Lawyer Program

Kentucky Bar Association New Lawyer Program February 6 – 7, 2020 Lexington Convention Center Lexington , Kentucky Presented by: The Kentucky Bar Association CLE Commission and Young Lawyers Division ©2020 by the Kentucky Bar Association Continuing Legal Education Commission Lori J. Alvey, Sonja M. Blackburn, Caroline J. Carter, Mary E. Cutter, EmaLeigh C. Haines, Editors All rights reserved Published January 2020 Editor’s Note: The materials included in this New Lawyer Program seminar book are intended to provide current and accurate information about the subject matter covered. The program materials were compiled for you by volunteer authors and from national legal publications. No representation or warranty is made concerning the application of the legal or other principles discussed by the instructors to any specific fact situation, nor is any prediction made concerning how any particular judge or jury will interpret or apply such principles. The proper interpretation or application of the principles discussed is a matter for the considered judgment of the individual legal practitioner. The faculty and staff of the New Lawyer Program disclaim liability therefor. Attorneys using these materials or information otherwise conveyed during the program, in dealing with a specific legal matter, have a duty to research original and current sources of authority. The Kentucky Bar Association would like to give special thanks to the volunteer authors who contributed to this program handbook. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS PROGRAM AGENDA .................................................................................................... v DAY ONE – GENERAL SESSIONS Program Introduction and Welcome Program Introduction: Why Am I Here, Anyway? .......................................... 1 Kentucky Bar Association: What We Do for You ...................................... ….3 Kentucky Bar Association: Your Partner in the Profession ............................ -

Kentucky Bar Association’S VOL

MAY/JUNE 2017 KBA Individual Own Occupation Disability Plan from Metlife: Protect your income, your lifestyle and your practice from a disabling illness or injury. Available only through the KBA: • Discounted Unisex rates • Simplified non-medical application • No tax returns or W-2s required • Up to $10,000/mo coverage under age 50 • Liberal issue and participation limits Rates, Custom Quote & Online Application: NIAI.com Or contact Woody Long at [email protected] Call or Email TODAY | 800.928.6421 | [email protected] | www.NIAI.com Underwritten by: Metropolitan Life Insurance, 200 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10166 This issue of the Kentucky Bar Association’s VOL. 81, NO. 3 B&B-Bench & Bar was published in the month of May. COMMUNICATIONS & Contents PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE 2 President’s Page James P. Dady, Chair, Bellevue By: Mike Sullivan Paul Alley, Florence 4 A Brief History of the KBA Hotline Elizabeth M. Bass, Lexington By: Professor William H. Fortune James Paul Bradford, Paducah Frances E. Catron Cadle, Lexington 2017 KBA ANNUAL 6 Anne A. Chesnut, Lexington CONVENTION OVERVIEW Elizabeth A. Deener, Lexington Rachel Dickey, Louisville Features: Appellate Advocacy Tamara A. Fagley, Lexington 12 Supreme Court in Review: Reengineering the Mark Flores, Fort Worth, Texas Cathy W. Franck, Crestwood Work of the Appellate Courts By: Susan Stokley Clary Lonita Baker Gaines, Louisville William R. Garmer, Lexington 16 Will Common Law Stagnate in an Era of Declining Trials? Laurel A. Hajek, Louisville Another Test of Time P. Franklin Heaberlin, Prestonsburg By: Justice Daniel J. Venters Judith B. Hoge, Louisville 20 Appellate Advocacy in Federal Court Jessica R. -

Model Guideline for the Utilization of Legal Assistant

Model Guidelines For The Utilization Of Legal Assistant Services The following advisory guidelines were adopted by the Idaho State Bar membership during the 1992 resolution process. These guidelines are an attempt to identify the proper role of a legal assistant, and to define the lawyer’s supervisory role. Because the Model Guidelines are advisory only, they do not conflict with the Idaho Rules of Professional Conduct. There are 10 guidelines, covering a lawyer’s supervisory and training responsibilities, the permissible scope of delegation, how legal assistants are held out to clients, the courts and the public, and guidelines for the billing of a legal assistant’s time. Preamble assistant’s education, training, and experience, and for ensuring that the legal assistant is familiar with the responsibilities of attorneys and legal assistants under the State courts, bar associations, or bar committees in at least 4 seventeen states have prepared recommendations1 for the applicable rules governing professional conduct. utilization of legal assistant services.2 While their content Under principles of agency law and rules governing the varies, their purpose appears uniform: to provide lawyers conduct of attorneys, lawyers are responsible for the actions and the work product of the non-lawyers they employ. Rule with a reliable basis for delegating responsibility for 5 performing a portion of the lawyer’s tasks to legal assistants. 5.3 of the Model Rules requires that partners and supervising The purpose of preparing model guidelines is not to contradict attorneys ensure that the conduct of non-lawyer assistants is the guidelines already adopted or to suggest that other compatible with the lawyer’s professional obligations. -

The Ethical Oregon Lawyer 2006 Revision

Completely revised! The Ethical Oregon Lawyer 2006 Revision Your #1 go-to desk reference for ethics questions and answers . now includes discussions about Oregon’s new Rules of Professional Conduct and the RPCs of Washington, Idaho, and Utah. No matter what your practice area, you need to follow the disciplinary rules—for yourself and for your clients. But you often have questions about how to do that. And with the recent change from the old DRs to the new Oregon RPCs, you may wonder if the answers you knew have changed. The Ethical Oregon Lawyer is the best source for answers to these ethics questions, and more: How are attorney fees governed? What constitutes competent representation? What sanctions are available in appellate court? Who is the client for an insurance defense lawyer? What constitutes an ex parte contact in a pending case? Who holds the lawyer-client privilege in the corporate context? What limitations do lawyers face when advertising their services? What rights does an accused lawyer have in a disciplinary hearing? When does a lawyer’s self-interest conflict with the client’s interests? How do the new Oregon RPCs affect a lawyer’s duty of confidentiality? Under what circumstances may a lawyer ethically withdraw from a case? What ethical limits are placed on a lawyer in negotiating on a client’s behalf? How do you avoid ethical conflicts when managing, organizing, or selling a law firm? What ethical issues arise when you hire a mental health professional to assess your client’s mental capacity? May a lawyer represent a current client whose interests conflict with those of a former client? Plus, each chapter highlights the major differences between Oregon’s Rules of Professional Conduct and the RPCs of Washington, Utah, and Idaho. -

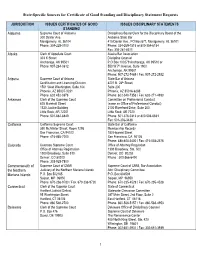

State-Specific Sources for Certificate of Good Standing and Disciplinary Statement Requests

State-Specific Sources for Certificate of Good Standing and Disciplinary Statement Requests JURISDICTION ISSUES CERTIFICATES OF GOOD ISSUES DISCIPLINARY STATEMENTS STANDING Alabama Supreme Court of Alabama Disciplinary Board Clerk for the Disciplinary Board of the 300 Dexter Ave. Alabama State Bar Montgomery, AL 36104 415 Dexter Ave., PO Box 671, Montgomery, AL 36101 Phone: 334-229-0700 Phone: 334-269-1515 or 800-354-6154 Fax: 334-261-6311 Alaska Clerk of Appellate Court Alaska Bar Association 303 K Street Discipline Counsel Anchorage, AK 99501 P.O Box 100279 Anchorage, AK 99510 or Phone: 907-264-0612 550 W 7th Avenue, Suite 1900 Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: 907-272-7469 / Fax: 907-272-2932 Arizona Supreme Court of Arizona State Bar of Arizona Certification and Licensing Division 4201 N. 24th Street, 1501 West Washington, Suite 104 Suite 200 Phoenix, AZ 85007-3231 Phoenix, AZ 85016-6288 Phone: 602 452-3378 Phone: 602-340-7353 / Fax: 602-271-4930 Arkansas Clerk of the Supreme Court Committee on Professional Conduct 625 Marshall Street (same as Office of Professional Conduct) 1320 Justice Building 2100 Riverfront Drive, Suite 200 Little Rock, AR 72201 Little Rock, AR 7220 Phone: 501-682-6849 Phone: 501-376-0313 or 800-506-6631 Fax: 501-376-3438 California California Supreme Court State Bar of California 350 McAllister Street, Room 1295 Membership Records San Francisco, CA 94102 180 Howard Street Phone: 415-865-7000 San Francisco, CA 94105 Phone: 888-800-3400 / Fax: 415-538-2576 Colorado Colorado Supreme Court Office of Attorney Regulation Office of Attorney Registration 1300 Broadway, Ste. -

1 No. 19-35463 United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

(1 of 41) Case: 19-35463, 11/13/2019, ID: 11498160, DktEntry: 30-1, Page 1 of 2 No. 19-35463 United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ________________ DANIEL Z. CROWE, OREGON CIVIL LIBERTIES ATTORNEYS; AND LAWRENCE K. PETERSON, Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. STATE BAR OF OREGON, Defendant-Appellee, _______________________________________________ On Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Oregon, Portland Division Case No. 3:18-cv-02139-JR Honorable Michael H. Simon MOTION OF STATE BAR OF ARIZONA FOR LEAVE TO FILE AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF SUPPORTING APPELLEE Mary R. O’Grady Kimberly Friday OSBORN MALEDON, P.A. 2929 North Central Avenue, Suite 2100 Phoenix, Arizona 85012 (602) 640-9000 [email protected] Attorneys for State Bar of Arizona 1 (2 of 41) Case: 19-35463, 11/13/2019, ID: 11498160, DktEntry: 30-1, Page 2 of 2 The State Bar of Arizona (“Arizona”) moves for leave to file an amicus brief supporting the State Bar of Oregon in this case. The proposed brief is filed with this motion. The State Bar of Oregon consents to Arizona filing this brief. Appellants oppose the filing of this brief. Arizona has an interest in the court’s decision in this case because Arizona, like Oregon, has an integrated bar in which membership is required. The amicus brief will provide information on state bars in jurisdictions other than Oregon to provide the Court with a broader perspective on the varied systems for regulating the practice of law. Because of the potentially broad impact of the court’s decision, information on other state bars should be useful to the court.