Materials Included in This Diversity and Inclusion Summit Seminar Book Are Intended to Provide Current and Accurate Information About the Subject Matter Covered

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethics 2000 Committee Members

ETHICS 2000 COMMITTEE MEMBERS Chair Robert I. Cusick [July 2003 – March 2006] 1201 New York Avenue Suite 500 Washington, DC 202-482-9292 [email protected] Chair Dulaney L. O’Roark [March 2006 Forward] 914 Albemarle Court Louisville, KY 40222 502-429-6457 [email protected] John T. Ballantine 2000 PNC Plaza 500 West Jefferson Street, Suite 2000 Louisville, KY 40202 502-582-1601 [email protected] Professor Edward C. Brewer Northern Kentucky University NH 556 Nunn Drive Highland Heights, KY 41099 859-572-6943 [email protected] Donald H. Combs Post Office Drawer 31 Pikeville, KY 41502-0031 606-437-6226 [email protected] Jane Winkler Dyche 402 W. Fifth St. Post Office Box 5156 London, KY 40745 606-877-2991 [email protected] Linda S. Ewald University of Louisville Law School Belknap Campus Louisville, KY 40292 502-852-7362 [email protected] D. Scott Furkin Administrative Office of the Courts 100 Millcreek Park Frankfort, KY 40601 502-573-2350 [email protected] Sheldon G. Gilman Lynch, Cox, Gilman & Mahan, PSC 500 W Jefferson Street, Suite 2100 Louisville, KY 40202 502-589-4215 [email protected] Linda A. Gosnell Kentucky Bar Association 514 West Main Street Frankfort, KY 40601 502-564-3795 [email protected] Jane E. Graham 401 W. Main St., Ste 314 Lexington, KY 40507 859-266-4092 [email protected] Janet Jakubowicz 3300 National City Tower 101 South 5th Street Louisville, KY 40202 502-589-4200 [email protected] William E. Johnson 326 West Main Street Frankfort, KY 40601 502-875-6000 [email protected] Justice John D. -

KBA President J. Stephen Smith and Vicki Prichard at Home in Ft. Mitchell

JULY/AUGUST 2019 KBA President J. Stephen Smith and Vicki Prichard at home in Ft. Mitchell Individual Own Occupation Disability Coverage for Kentucky Attorneys Affordable KBA Rates from Metlife KBA Member Semiannual Rates Monthly Coverage Amount: $3,000 $5,000 $10,000 Under 30 yrs $152 $252 $502 30-39 yrs $213 $354 $705 40-49 yrs $352 $585 $1,167 ✓ No Medical Exam (Under Age 50) ✓ No Tax Returns ✓ Apply for up to $10,000/month Coverage ✓ Residual Disability Coverage ✓ Industry Standard Disability Definition ✓ Easy Online Application Visit www.NIAI.com/Attorneys for KBA quotes and application Call or Email TODAY | 800.928.6421 | [email protected] | www.NIAI.com This issue of the Kentucky Bar Association’s VOL. 83, NO. 4 B&B-Bench & Bar was published in the month of July. COMMUNICATIONS & PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Contents James P. Dady, Chair, Bellevue 2 President’s Page Paul Alley, Florence By: J. Stephen Smith Elizabeth M. Bass, Gallatin, Tenn. Rhonda J. Blackburn, Pikeville 5 Q&A with KBA President J. Stephen Smith Jenn L. Brinkley, Pensacola, Fla. 8 2019 KBA Annual Convention Wrap Up Frances E. Catron Cadle, Lexington Anne A. Chesnut, Lexington Features: Legislative Update Elizabeth A. Deener, Lexington Tamara A. Fagley, Lexington 18 Kentucky, Hemp, and the Law Cathy W. Franck, Crestwood By: Ryan Quarles, Kentucky Commissioner of Agriculture Lonita Baker Gaines, Louisville 22 Legislative Update on Abortion Access in Kentucky William R. Garmer, Lexington By: Jennifer L. Brinkley P. Franklin Heaberlin, Prestonsburg Judith B. Hoge, Louisville 26 Open Courts: Section 14 of the Kentucky Constitution Jessica R. -

Formal Opinion

· :. - FORMAL ETHICS OPINION NO. 127 The Idaho State Bar Committee on Ethics and Professional Responsibility has been requested to render an opinion concerning the propriety of a J.a1Al'yer placing telephone calls to residents of the lawyer's area of practice, selected at random, as a follow up to an advertisement distributed to the public at large. The advertisement says in part: H$25.00 cash if we call your number and you can answer two questions about this page. We will make random callsH. The specific question is whether placing the random calls would violate the Idaho Rules of Professional Conduct. Rule 7.3 of the Idaho Rules of Professional Conduct is controlling: Direct contact with Prospective Clients A lawyer may not solicit professional employment from a prospective client with whom the lawyer has no family or prior professional relationship, by mail, in-person or otherwise, when a significant motive for the lawyer's doing so is the lawyer's pecuniary gain. The term HsolicitH includes contact in person, by telephone or telegraph, by letter or other writing, or by other communication directed to a specific recipient, but does not include letters addressed or advertising circulars distributed generally to persons not known to need legal services of the kind provided by the lawyer in a particular matter, but who are so situated that they might in general find such services useful. ETHICS OPINION - 1 The Supreme Court of the united States held, in Ohralik vs. Ohio State Bar Association, 436 U.S. 447 (1978), that a State may categorically ban in-person solicitation by lawyers for pecuniary gain. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Nationally, approximately 40% of new attorneys work at firms consisting of more than 50 lawyers. Therefore, a large percentage of practicing attorneys work for small firms (fewer than 50 attorneys). Small firms generally do not have formalized recruiting procedures or a set “hiring season” when they recruit summer law clerks, school-year law clerks, or entry-level attorneys. Instead, these firms hire on an as-needed basis, and they hire year round. To secure employment with a small firm, students and lawyers alike need to be proactive in getting their name and interests out in the community. Applicants should not only apply directly to these firms, but they should connect via law school, community, and bar association activities. In this directory, you will find state-by-state hyperlinks to regional directories, bar associations, newspapers, and job banks that can be used to jump-start a small firm search. ALABAMA State/Regional Bar Associations Alabama Bar Association: http://www.alabar.org Birmingham Bar Association: http://www.birminghambar.org Mobile Bar Association: http://www.mobilebar.org Specialty Bar Associations Alabama Defense Lawyers Association: http://www.adla.org Alabama Trial Lawyers Association: http://www.alabamajustice.org Major Newspapers Birmingham News: http://www.al.com/birmingham Mobile Register: http://www.al.com/mobile Legal & Non-Legal Resources & Publications State Lawyers.com: http://alabama.statelawyers.com EINNEWS: http://www.einnews.com/alabama Birmingham Business Journal: http://birmingham.bizjournals.com -

In the District Court of the Virgin Islands Division of St

Case: 3:11-cv-00078-CVG-RM Document #: 200 Filed: 10/31/11 Page 1 of 10 IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE VIRGIN ISLANDS DIVISION OF ST. THOMAS AND ST. JOHN POLICE BENEVOLENT ASSOCIATION, LOCAL 1910, ET AL., CASE NO. 2011B78 Plaintiffs, v. GOVERNMENT OF THE VIRGIN ISLANDS, ET AL., Defendants. ST. CROIX FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, LOCAL 1826, ET AL., CASE NO. 2011B79 Plaintiffs, v. GOVERNMENT OF THE VIRGIN ISLANDS, ET AL., Defendants. UNITED STEEL, PAPER & FORESTRY, RUBBER, MANUFACTURING, ET AL., CASE NO. 2011B76 Plaintiffs, v. GOVERNMENT OF THE VIRGIN ISLANDS, ET AL., Defendants. Case: 3:11-cv-00078-CVG-RM Document #: 200 Filed: 10/31/11 Page 2 of 10 Lead Case: Police Ben. Ass=n, et al. v. GVI, et al. Civil No. 2011-78 Memorandum and Order Page 2 AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, LOCAL 1825, ET AL., CASE NO. 2011B77 Plaintiffs, v. GOVERNMENT OF THE VIRGIN ISLANDS, ET AL., Defendants. INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF FIREFIGHTERS LOCAL 2125, ET AL., CASE NO. 2011B81 Plaintiffs, v. GOVERNMENT OF THE VIRGIN ISLANDS, ET AL., Defendants. MEMORANDUM AND ORDER Before the Court is the Legislature of the Virgin Islands= motion to disqualify Nizar A. DeWood, Esq., as counsel for plaintiffs Police Benevolent Association (Local 1910, St. Croix Chapter), Law Enforcement Supervisors Union (Local 119, St. Croix Chapter), Arthur A. Joseph, Sr. and Freddy Ortiz, Jr. (collectively, the “PBA/LESU”). The Legislature contends that disqualification is appropriate because Attorney DeWood wrongfully communicated with members of the Legislature in violation of Rule 4.2 of the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct. Plaintiffs opposes the motion, arguing that any contacts that occurred were prior to the initiation of the lawsuit and therefore outside the scope of Rule 4.2, or were otherwise authorized pursuant to Rule 4.2. -

Kentucky Bar Association New Lawyer Program

Kentucky Bar Association New Lawyer Program February 6 – 7, 2020 Lexington Convention Center Lexington , Kentucky Presented by: The Kentucky Bar Association CLE Commission and Young Lawyers Division ©2020 by the Kentucky Bar Association Continuing Legal Education Commission Lori J. Alvey, Sonja M. Blackburn, Caroline J. Carter, Mary E. Cutter, EmaLeigh C. Haines, Editors All rights reserved Published January 2020 Editor’s Note: The materials included in this New Lawyer Program seminar book are intended to provide current and accurate information about the subject matter covered. The program materials were compiled for you by volunteer authors and from national legal publications. No representation or warranty is made concerning the application of the legal or other principles discussed by the instructors to any specific fact situation, nor is any prediction made concerning how any particular judge or jury will interpret or apply such principles. The proper interpretation or application of the principles discussed is a matter for the considered judgment of the individual legal practitioner. The faculty and staff of the New Lawyer Program disclaim liability therefor. Attorneys using these materials or information otherwise conveyed during the program, in dealing with a specific legal matter, have a duty to research original and current sources of authority. The Kentucky Bar Association would like to give special thanks to the volunteer authors who contributed to this program handbook. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS PROGRAM AGENDA .................................................................................................... v DAY ONE – GENERAL SESSIONS Program Introduction and Welcome Program Introduction: Why Am I Here, Anyway? .......................................... 1 Kentucky Bar Association: What We Do for You ...................................... ….3 Kentucky Bar Association: Your Partner in the Profession ............................ -

Kentucky Bar Association’S VOL

MAY/JUNE 2017 KBA Individual Own Occupation Disability Plan from Metlife: Protect your income, your lifestyle and your practice from a disabling illness or injury. Available only through the KBA: • Discounted Unisex rates • Simplified non-medical application • No tax returns or W-2s required • Up to $10,000/mo coverage under age 50 • Liberal issue and participation limits Rates, Custom Quote & Online Application: NIAI.com Or contact Woody Long at [email protected] Call or Email TODAY | 800.928.6421 | [email protected] | www.NIAI.com Underwritten by: Metropolitan Life Insurance, 200 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10166 This issue of the Kentucky Bar Association’s VOL. 81, NO. 3 B&B-Bench & Bar was published in the month of May. COMMUNICATIONS & Contents PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE 2 President’s Page James P. Dady, Chair, Bellevue By: Mike Sullivan Paul Alley, Florence 4 A Brief History of the KBA Hotline Elizabeth M. Bass, Lexington By: Professor William H. Fortune James Paul Bradford, Paducah Frances E. Catron Cadle, Lexington 2017 KBA ANNUAL 6 Anne A. Chesnut, Lexington CONVENTION OVERVIEW Elizabeth A. Deener, Lexington Rachel Dickey, Louisville Features: Appellate Advocacy Tamara A. Fagley, Lexington 12 Supreme Court in Review: Reengineering the Mark Flores, Fort Worth, Texas Cathy W. Franck, Crestwood Work of the Appellate Courts By: Susan Stokley Clary Lonita Baker Gaines, Louisville William R. Garmer, Lexington 16 Will Common Law Stagnate in an Era of Declining Trials? Laurel A. Hajek, Louisville Another Test of Time P. Franklin Heaberlin, Prestonsburg By: Justice Daniel J. Venters Judith B. Hoge, Louisville 20 Appellate Advocacy in Federal Court Jessica R. -

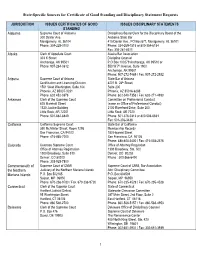

State-Specific Sources for Certificate of Good Standing and Disciplinary Statement Requests

State-Specific Sources for Certificate of Good Standing and Disciplinary Statement Requests JURISDICTION ISSUES CERTIFICATES OF GOOD ISSUES DISCIPLINARY STATEMENTS STANDING Alabama Supreme Court of Alabama Disciplinary Board Clerk for the Disciplinary Board of the 300 Dexter Ave. Alabama State Bar Montgomery, AL 36104 415 Dexter Ave., PO Box 671, Montgomery, AL 36101 Phone: 334-229-0700 Phone: 334-269-1515 or 800-354-6154 Fax: 334-261-6311 Alaska Clerk of Appellate Court Alaska Bar Association 303 K Street Discipline Counsel Anchorage, AK 99501 P.O Box 100279 Anchorage, AK 99510 or Phone: 907-264-0612 550 W 7th Avenue, Suite 1900 Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: 907-272-7469 / Fax: 907-272-2932 Arizona Supreme Court of Arizona State Bar of Arizona Certification and Licensing Division 4201 N. 24th Street, 1501 West Washington, Suite 104 Suite 200 Phoenix, AZ 85007-3231 Phoenix, AZ 85016-6288 Phone: 602 452-3378 Phone: 602-340-7353 / Fax: 602-271-4930 Arkansas Clerk of the Supreme Court Committee on Professional Conduct 625 Marshall Street (same as Office of Professional Conduct) 1320 Justice Building 2100 Riverfront Drive, Suite 200 Little Rock, AR 72201 Little Rock, AR 7220 Phone: 501-682-6849 Phone: 501-376-0313 or 800-506-6631 Fax: 501-376-3438 California California Supreme Court State Bar of California 350 McAllister Street, Room 1295 Membership Records San Francisco, CA 94102 180 Howard Street Phone: 415-865-7000 San Francisco, CA 94105 Phone: 888-800-3400 / Fax: 415-538-2576 Colorado Colorado Supreme Court Office of Attorney Regulation Office of Attorney Registration 1300 Broadway, Ste. -

Lawyer Wellness

IN THIS ISSUE Lawyer Wellness POWERING PAYMENTS FOR THE Trust Payment IOLTA Deposit Amount LEGAL $ 1,500.00 INDUSTRY Reference The easiest way to accept credit, NEW CASE debit, and eCheck payments Card Number **** **** **** 4242 The ability to accept payments online has become vital for all firms. When you need to get it right, trust LawPay's proven solution. As the industry standard in legal payments, LawPay is the only payment solution vetted and approved by all 50 state bar associa- tions, 60+ local and specialty bars, the ABA, and the ALA. Developed specifically for the legal industry to ensure trust account compliance and deliver the most secure, PCI-compliant technology, LawPay is proud to be the preferred, long-term payment partner for more than 50,000 law firms. Proud Member Benefit Provider ACCEPT MORE PAYMENTS WITH LAWPAY 877-958-8153 | lawpay.com/kybar This issue of the Kentucky Bar Association’s VOL. 85, NO. 3 B&B-Bench & Bar was published in the month of May. COMMUNICATIONS & PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE James P. Dady, Chair, Bellevue Contents Paul Alley, Florence 2 President’s Page Elizabeth M. Bass, Gallatin, Tenn. By Tom Kerrick Rhonda J. Blackburn, Pikeville Jenn L. Brinkley, Pensacola, Fla. 6 Justice Donald C. Wintersheimer: A Memorial Rachelle C. Bolton, Lexington By James P. Dady Frances E. Catron Cadle, Lexington 10 2021 KBA AC Wrap Up Elizabeth A. Deener, Lexington Cathy W. Franck, Crestwood Features: Lawyer Wellness Lonita Baker Gaines, Louisville 12 Kentucky Bar Comes to Grips with Lawyer Suicide William R. Garmer, Lexington By James P. Dady P. Franklin Heaberlin, Prestonsburg Judith B. -

Bench & Bar Magazine

Volume 75 Number 3 May 2011 In this Issue: • Health Care Issues in the Legal Forefront • Proposed Amendments to the Supreme Court Rules • Annual Convention Special Events oodford R. Long, President NIA Does your ordinary level term life insurance look like this? *20 year level term policy on W Year 1-20: $940 Year 21: $28,280 * Like me, most of our clients will either need or want to keep their life insurance longer than planned. Many will not be able to requalify or renew their ordinary term insurance policies. The KBA term life plan is guaranteed renewable to age 75. Available in 10, 20, and yearly renewable plans, the KBA plan is built to protect your future, not terminate at the level period end, or lapse with prohibitive renewal premiums. Plan for the future with the KBA Life Plan. www.niai.com - Woody Long, CLU NATIONAL INSURANCE NIA AGENCYInc. Professional Association & Affinity Insurance Services www.niai.com • Phone: 502 425-3232 • [email protected] This issue of the Kentucky Bar Association’s Bench & Bar was CONTENTS published in the month of May. Communications & Publications Committee Health Care Frances E. Catron, Chair, Frankfort Paul Alley, Florence Elizabeth M. Bass, Lexington 10 Ensuring the Health Care Worker Can Perform the Sandra A. Bolin, Berea Essential Functions of Their Position in the Michael A. Breen, Bowling Green Christopher S. Burnside, Louisville Increasingly Restricted Legal Environment David C. Condon, Owensboro Governing Hiring and Disability Accommodation Ashlee D. Coomer, Petersburg James P. Dady, Bellevue By Ronald L. Lester Alexander F. Edmondson, Covington Judith D. -

Social Media and Legal Ethics: the Ethical Way to Use Those Tweets, Likes and Links to Your Advantage

SOCIAL MEDIA AND LEGAL ETHICS: THE ETHICAL WAY TO USE THOSE TWEETS, LIKES AND LINKS TO YOUR ADVANTAGE Sponsor: Young Lawyers Division CLE Credit: 1.0 ethics Thursday, June 14, 2018 10:50 - 11:50 a.m. Bluegrass Ballroom II Lexington Convention Center Lexington, Kentucky A NOTE CONCERNING THE PROGRAM MATERIALS The materials included in this Kentucky Bar Association Continuing Legal Education handbook are intended to provide current and accurate information about the subject matter covered. No representation or warranty is made concerning the application of the legal or other principles discussed by the instructors to any specific fact situation, nor is any prediction made concerning how any particular judge or jury will interpret or apply such principles. The proper interpretation or application of the principles discussed is a matter for the considered judgment of the individual legal practitioner. The faculty and staff of this Kentucky Bar Association CLE program disclaim liability therefore. Attorneys using these materials, or information otherwise conveyed during the program, in dealing with a specific legal matter have a duty to research original and current sources of authority. Printed by: Evolution Creative Solutions 7107 Shona Drive Cincinnati, Ohio 45237 Kentucky Bar Association TABLE OF CONTENTS The Presenters ................................................................................................................. i Why Use Social Media at All? Because you will be a better advocate. Also, some day you might have to ..................... 1 Don't Get Ensnared in Authentication Issues …Unless you want to be a witness in your own case ...................................................... 4 Like a Friend: Contact with Represented Parties and Unrepresented Individuals ............ 5 Remember: Jurors Have Linkedin, Twitter, and Facebook, Just Like the Rest of Us ................................................................................................. -

Benchbar Index 1936-1982.Pdf

KENTUCKY BENCH AND BAR KENTUCKY BAR JOURNAL KENTUCKY STATE BAR JOURNAL CUMULATIVE INDEX Volume One through Volume Forty-six 1936 - 1982 Compiled By Evelyn M. Lock-vmod Catalog and Research Librarian State Law Library Frankfort, Kentucky • 1984 COMMONWEALTH OF KENTUCKY ST AfE LAW LIBRARY KENTUCKY BENCH AND BAR KENTUCKY BAR JOURNAL KENTUCKY STATE BAR JOURNAL Cumulative Index Volume One through Volume Forty-six 1936 - 1982 INTRODUCTION How To Use This Index This index to articles includes subjects, authors, and cases in one alphabetical arrangement. All signed articles, plus selected additional ones, are included. Kentucky Bench and Bar was known as Kentucky State Bar Journal from volume 1, 1936, through volume 35, July, 1971, and as the Kentucky Bar Journal from volume 35, October, 1971, throu;_sh ·volume 38, 1974. Alphabetical listings, by title, of articles dealing with particular subjects, followed by the authors' last names, the volumes, page numbers on which articles begin, and month and year of journals may be found by subject heading, as in the sample entry below: LEGAL EDUCATION, CONTINUING Continuing legal education in Louisville and Jefferson county, by Marshall 23:109 Mar '59 • The article above, "Continuing legal education in Louisville and Jefferson county," may be found in volume 23, page 109 of the Harch, 1959 issue of Kentucky State Bar_ Journal. The same article may also be found under the author, e.g., HARSHALL, DANIEL T., JR. Continuing legal education in Louisville and Jefferson county 23:109 Mar '59 Subject headings are frequently subdivided, e.g., COURTHOUSES -- PRESERVATION or, COURTS -- REVISION Subjects are cross referenced to related topics, or to topics used in the index from one which is not, e.g., INTERNATIONAL LAW See also TREATIES; WAR CRil1ES; WORLD LAW or, GARNISHMENT See ATTACHHENT AND GAill~ISHHENT j ii Court cases are listed only if an article is written concerning them.