Supportable Retail Capacity: a Downtown Vancouver Case'study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rescheduled Public Hearing Transcript

TRANSCRIPT OF THE RESCHEDULED PUBLIC HEARING HELD IN THE COUNCIL CHAMBER, CITY HALL, 141 WEST 14th STREET, NORTH VANCOUVER, B.C., ON MONDAY, MAY 16, 2005 AT 7:00 P.M. PRESENT: COUNCIL MEMBERS STAFF MEMBERS Mayor B.A. Sharp A.K. Tollstam, City Manager Councillor R.C. Clark S.E. Dowey, City Clerk Councillor R.J. Fearnley J.M. Rowe, Assistant City Clerk Councillor R.N. Heywood G. Penway, Assistant City Planner Councillor B.W. Perrault F.A. Smith, Director, Community Development K. Russell, Development Planner ABSENT Councillor C.R. Keating Councillor D.R. Mussatto Re: Bylaw No. 7687 – 901 West 3rd Street – File: 3345-02 3W 901 The Rescheduled Public Hearing was called to order at 7:00 p.m. Mayor B.A. Sharp Ms. Dowey! Ms. S.E. Dowey, City Clerk Thank you Your Worship. Bylaw No. 7687 is to amend the text of CD-252 (Comprehensive Development 252 Zone) legally described as Lot 1, Resub 6, Block X, D.L. 265, Plan 11806, located at 901 West 3rd Street, by adding “retail building supply establishment” to the list of permitted uses in this zone. The applicant is Griffin Holding Corp./Michael Rosen & Associates and Council will consider this under item 6, Your Worship. Mayor Sharp Mr. Penway! Mr. G. Penway, Development Planner Thank you Your Worship. We are talking about a site which is the corner of 3rd Street and Hanes, so in this aerial photograph, you will see its on the corner of the property here. It would be the Southeast corner of the intersection at Hanes and 3rd Street. -

Canada-2013-Finalists.Pdf

TRADITIONAL MARKETING ADVERTISING Centres 150,000 to 400,000 sq. ft. of total retail space Identity Crisis Rescued 10 Dundas East Toronto, Ontario Management Company: Bentall Kennedy (Canada) LP Owner: 10 Dundas Street Ltd. One World in the Heart of Your Community Jane Finch Mall Toronto, Ontario Management Company: Arcturus Realty Corporation Owner: Brad-Jay Investments Limited At the Heart of the Community Les Galeries de Hull Gatineau, Quebec Management Company/Owner: Ivanhoe Cambridge Here’s to the Best Things in Life Lynden Park Mall Brantford, Ontario Management Company/Owner: Ivanhoe Cambridge Must Visit MEC Montreal Eaton Centre Montreal, Quebec Management Company/Owner: Ivanhoe Cambridge Centres 400,000 to 750,000 sq. ft. of total retail space Break Out Your Style Cornwall Centre Regina, Saskatchewan Management Company: 20 Vic Management Inc. Owner: Kingsett Capital & Ontario Pension Board The Really Runway Dufferin Mall Toronto, Ontario Management Company: Primaris Management Inc. Owner: H&R Reit Les Rivieres: Inspired by Trends Les Rivières Shopping Centre Trois-Rivières, Quebec Management Company: Ivanhoe Cambridge Owner: Ivanhoe Cambridge & Sears Canada Medicine Hat Mall Motherload Medicine Hat Mall Medicine Hat, Alberta Management Company: Primaris Management Inc. Owner: H & R Reit Crate&Barrel | OAKRIDGE · SINCE MARCH 21, 2013 Oakridge Centre Vancouver, British Columbia Management Company/Owner: Ivanhoe Cambridge Wahoo! Uptown Victoria, British Columbia Management Company: Morguard Investments Limited Owner: Greystone Centres 750,000 to 1,000,000 sq. ft. of total retail space Entrepôts de Marques - Brand Factory Marché Central Montréal, Québec Management Company: Bentall Kennedy (Canada) LP Owner: bcIMC Realty Corporation The World Of Fashion In 200 Stores Place Rosemère Rosemère, Québec Management Company: Morguard Investments Limited Owner: Rosemère Centre Properties Limited An Independent Style Southcentre Calgary, Alberta Management Company /Owner: Oxford Properties Group St. -

STARBUCKS HOLIDAY HOURS Christmas

STARBUCKS HOLIDAY HOURS Christmas Day - December 25 Store Province City Store Name Open Close Number AB Airdrie Sierra Springs - Airdrie 05.30.00 22.00.00 4808 AB Airdrie Tower Lane Mall 06.00.00 22.00.00 4937 AB Airdrie Dickson Crossing - Airdrie 06.00.00 22.00.00 4997 AB Banff Banff Avenue Mall 09.30.00 17.00.00 4457 AB Beaumont Gallerie Beaumont - Montalet & 50th 06.00.00 22.00.00 16143 AB Calgary Kensington 09.00.00 16.00.00 4242 AB Calgary 17th Avenue 08.30.00 17.00.00 4261 AB Calgary 17th Avenue 09.00.00 21.00.00 4261 AB Calgary 4th Street & 23rd 08.30.00 17.00.00 4272 AB Calgary Glenmore Landing 09.30.00 16.00.00 4273 AB Calgary Britannia 07.00.00 18.00.00 4280 AB Calgary Centre & 9th 08.00.00 16.00.00 4316 AB Calgary Gateway South / Chapters 08.00.00 19.00.00 4324 AB Calgary Crowfoot / Chapters 10.00.00 16.00.00 4325 AB Calgary Country Hills 10.00.00 16.00.00 4383 AB Calgary Sunridge Pwr Cntr/Chapters 10.00.00 16.00.00 4385 AB Calgary Panorama Hills 08.30.00 21.00.00 4399 AB Calgary Willow Park Village 09.00.00 16.00.00 4411 AB Calgary Bankers Hall 05.30.00 20.30.00 4412 AB Calgary Marda Loop 09.30.00 16.30.00 4413 AB Calgary 16th & 11th 08.30.00 17.00.00 4423 AB Calgary Chinook II 07.00.00 22.30.00 4447 AB Calgary TD Square 05.30.00 20.30.00 4513 AB Calgary Coventry Hills Ctr-Country&Harvest 09.00.00 16.30.00 4543 AB Calgary Tuscany Drive Market 10.00.00 16.00.00 4549 AB Calgary Bankers Hall II 05.30.00 20.30.00 4734 AB Calgary Hotel Arts - 12 Ave SW 10.00.00 16.00.00 4819 AB Calgary Hotel Arts - 12 Ave SW 09.00.00 16.00.00 4819 -

LVSA NEWS Mollie Nye House 940 Lynn Valley Road North Vancouver, BC V7J 1Z7 604-987-5820 Email: [email protected] Website

LVSA NEWS Mollie Nye House 940 Lynn Valley Road North Vancouver, BC V7J 1Z7 604-987-5820 Email: [email protected] Website: www.lvsa.ca November – December 2018 Issue Inside this issue: CHRISTMAS LUNCHEON for LVSA MEMBERS Page 2 - Message from the Board Page 3 – November Hearty Lunch PLACE: CARDINAL HALL, 3590 Mountain Highway and Speaker (close to Lynn Valley School) at the corner of Page 5 – Bus Trips Page 6 - Christmas Luncheon Mountain Highway and Frederick Road Page 11 – LVSS News Transportation can be arranged. DATE: WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 5, 2018 Mollie Nye House DOORS OPEN: 12:00 NOON closed on November 12, 2018 for Remembrance Day Holiday COST: $23 includes The House closes at 4 pm on Thursday, December 20 FULLY CATERED CHRISTMAS LUNCH EON MENU and re-opens at 10 am and ENTERTAINMENT by the Parkgate Singers on Wednesday, January 2, 2019 for Christmas holidays Deadline for sign -up: Thursday, November 29 Message From The Board Back Row Left to Right: Dee Walker, Joanne Peterson, Jean Deane, Lorraine Campbell, Margaret Ballantine Front Row Left to Right: Georgina Duplissie, Carol Thompson, Jackie Hay, Susan Befus Fall is upon us – and that means flu season. This is just a reminder that the best way to stop the spread of infection is through careful and frequent hand washing using soap and warm water or applying foaming Microsan. You will find two dispensers within Mollie Nye House . one in the activity room and the other in the receptionist area. In the spirit of giving, LVSA is collecting items for the North Shore Youth Shelter run by Hollyburn Family Services. -

DISPENSING FEE REPORT - All Provinces Except ON

DISPENSING FEE REPORT - All provinces except ON Dispensing Fee Report January - March 2017 * In some provinces, a tiered fee schedule is in effect and thus some of the reported data may be skewed based upon such tiers. We strongly advise that you call the specific pharmacy of interest to ensure that you get the most updated, accurate fee information for the particular prescription that you require. Pharmacy Name Address(1) Address(2) City Prov. Postal Avg. Fee LOBLAW PHARMACY #4951 1050 YANKEE VALLEY ROAD AIRDRIE AB T4A2E4 $9.75 DRUGSTORE PHARMACY #1540 300 AIRDRIE ROAD NE AIRDRIE AB T4B3P2 $10.46 WALMART PHARMACY #1050 2881 MAIN STREET SW AIRDRIE AB T4B3G5 $11.78 SAFEWAY PHARMACY #8830 SOBEYS WEST INC. 505 MAIN STREET AIRDRIE AB T4B2B8 $11.88 SOBEYS PHARMACY #5172 AIRDRIE 100, 65 MACKENZIE WAY SW AIRDRIE AB T4B0V7 $11.98 POLARIS TRAVEL CLINIC AND PHARMACY 404-191 EDWARDS WAY SW AIRDRIE AB T4B3E2 $12.07 LONDON DRUGS #84 LONDON DRUGS LIMITED 110-2781 MAIN ST SW AIRDRIE AB T4B3S6 $12.10 SAVE-ON-FOODS PHARMACY #6602 OVERWAITEA PHARMACIES LTD 1400 MARKET STREET SE AIRDRIE AB T4A0K9 $12.22 SHOPPERS DRUG MART #2429 NARAYAN INVESTMENTS INC 2-804 MAIN STREET SE AIRDRIE AB T4B3M1 $12.25 SHOPPERS DRUG MART #2360 SELINGER DRUGGISTS LTD. 836 1ST AVE NW AIRDRIE AB T4B2R3 $12.26 SHOPPERS DRUG MART #2386 SELINGER DRUGGISTS LTD 310-505 MAIN ST AIRDRIE AB T4B3K3 $12.27 SHOPPERS DRUG MART #2328 WOLF PHARMACEUTICALS LTD 1200 MARKET STREET S.E. AIRDRIE AB T4A0K9 $12.28 PHARMASAVE #338 MELROSE DRUGS LTD. -

Allcreditorlist - 2020 09 08, 3

Dynamite - AllCreditorList - 2020 09 08, 3 Creditor Address1 Address2 Address3 Address4 Address5 1 Model Management, LLC 42 Bond St, 2nd Fl New York, NY 10012 10644579 Canada Inc 5592 Ferrier St Mount Royal, QC H4P 1M2 Canada 10644579 Canada Inc 5592 Ferrier St Mount-Royal, QC H4P 1M2 Canada 10927856 Canada Inc Apt 4, 7579 Rue Edouard Lasalle, QC H8P 1S6 Canada 11429876 Canada Inc 10 Ocean Ridge Dr Brampton, ON L6R 3K6 Canada 11588524 Canada Inc 4291 Rue Messier Montreal, QC H2H 2H6 Canada 1367826 Ontario Ltd 319 Brooke Ave Toronto, ON M5M 2L4 Canada 167081 Canada Inc 1625 Chabanel St, Ste 600 Montreal, QC H4N 2S7 Canada 174541 Canada Inc Laveurs De Vitres De L'Outaouais Inc 251 Rue Laramee Gatineau, QC J8Y 2Z4 Canada 1-800-Got-Junk? 887 Great Northern Way, Suite 301 Vancouver, BC V5T 4T5 Canada 1-800-Got-Junk? 9 Dibble St Toronto, ON M4M 2E7 Canada 1-800-Got-Junk? Commercial Services (Usa) LLC Dept 3419, P.O. Box 123419 Dallas, TX 75312-3419 1Ds Collective 11935 King St No. 22 Valley Village, CA 91607 1St Mechanical Services 303 Urie Dr Alpharetta, GA 30005 2422745 Ontario Inc 66 Sanders Dr Markham, ON L6B 0M3 Canada 2521506 Ontario Inc 120 Birkdale Rd Scarborough, ON M1P 3R5 Canada 2615476 Ontario Inc 169 Westphalia Ave Kianata, ON K2V 0E3 Canada 2Dev Inc 375-4000 Rue Saint-Ambroise Montreal, QC H4C 2C7 Canada 2Kw Enterprises LLC P.O. Box 5923 Concord, CA 94524 3249026 Canada Inc-Total Events 2360, 23E Ave Lachine, QC H8T 0A3 Canada 437 Inc (Adrien Bettio) 602 Richmond St W Toronto, ON M5V 1Y9 Canada 4450329 Canada Inc 5592, Rue Ferrier Ville Mont-Royal, QC H4P 1M2 Canada 5025045 Ontario Inc (Old 105620) 5387 Pl Belfield Montreal, QC 751797473 Canada 6053726 Canada Inc O/A Fuze Reps 69 Pelham Ave Toronto, ON M6N 1A5 Canada 7000766 Canada Inc 9655 Meilleur St Montreal, QC H3L 0A1 Canada 713949 Ontario Ltd Ottawa Management Office 1200 StLaurent Blvd Box 199 Ottawa, ON K1K 3B8 Canada 7599978 Canada Inc 54 Rue St-Jaques St. -

1 L;Kasdj Fkl; Kla;Sdj Fl;Kasj Dfkl;Sja Df

A&W TRADE MARKS LIMITED PARTNERSHIP (the “Partnership”) and A & W FOOD SERVICES OF CANADA INC. (“Food Services”) NINTH AMENDING AGREEMENT TO AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENCE AND ROYALTY AGREEMENT January 5, 2018 22483|3589363_2|RVEITCH NINTH AMENDING AGREEMENT TO AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENCE AND ROYALTY AGREEMENT This Ninth Amending Agreement made as of January 5, 2018 between A&W Trade Marks Limited Partnership, a limited partnership formed under the laws of British Columbia (the “Partnership”) and A & W Food Services of Canada Inc., a Canadian corporation (“Food Services”). WHEREAS the Partnership and Food Services entered into an Amended and Restated Licence and Royalty Agreement dated December 22, 2010, as amended January 5, 2011, January 5, 2012, January 5, 2013, January 5, 2014, January 5, 2015, January 5, 2016, December 19, 2016 and January 5, 2017 (as so amended, the “Licence and Royalty Agreement”) pursuant to which Schedule A thereto would be amended on an annual basis to add Proposed Additional A&W Outlets and to remove A&W Outlets that had Permanently Closed during the immediately preceding Reporting Period; AND WHEREAS Schedule B hereto sets out the Proposed Additional A&W Outlets to be added to the Royalty Pool on January 5, 2018, being the Adjustment Date for the Reporting Period commencing November 6, 2017; AND WHEREAS Schedule C hereto sets out the A&W Outlets that Permanently Closed during the Reporting Period ended November 5, 2017; AND WHEREAS Schedule D hereto sets out the conveyances and regrants of A&W Outlets contained in the Royalty Pool during the Reporting Period ended November 5, 2017; AND WHEREAS the parties hereto are desirous of amending the Licence and Royalty Agreement pursuant to the terms thereof to add the Proposed Additional A&W Outlets listed in Schedule B hereto to the Royalty Pool, to remove the Permanently Closed A&W Outlets listed in Schedule C hereto from the Royalty Pool, and to record the conveyances and regrants set out in Schedule D hereto. -

Customer Crisis Fund Application Advocates Contact Information and Locations

Customer Crisis Fund Application Advocates contact information and locations City Organization name Primary address Website Phone number 2420 Montrose Avenue, 604 859 7681 Abbotsford Abbotsford Abbotsford, BC abbotsfordcommunityservices.com ext. 207, 307 or 315 Community Services V2S 3S9 778 808 8883 (Spanish) Social Health & 411 MacKenzie St, Bella Coola Economic Development Bella Coola, BC clicklaw.bc.ca/organization/helpmap/1063 250 799 0044 Society of Bella Coola V0T 1C0 Multiple Sclerosis #1103 4720 Kingsway, Burnaby Society, BC & Burnaby, BC mssociety.ca 604 602 3236 Yukon Division V5H 4N2 #101 300 St. Ann’s Road, Opportunities Career Campbell River Campbell River, BC ocss.ca 250 286 3436 Services Society V9W 4C6 1625 McPhee Avenue, Wachiay Courtney Courtney, BC wachiay.org 250 338 7793 Friendship Centre V9N 5N4 Community Connections 3213th Avenue, Cranbrook Society Cranbrook, BC ccscranbrook.ca 250 426 2976 of Southeast BC V1C 2V3 10110 13th Street, South Peace Community Dawson Creek Dawson Creek, BC spcrs.ca 250 782 9174 Resources Society V1G 4H7 4807 Georgia Street, Sources Community Delta Delta, BC 604 946 0401 Resources Society V4K 2T1 10051 100th Avenue, Fort St. John Women’s Fort St John Fort St. John, BC fsjwrs.ca 250 787 1121 Resource Society V1J 1Y7 Upper Skeena 4305 Field Street, Hazelton Counselling & Legal Hazelton, BC usclas.com 250 842 5218 Assistance Society V0J 1Y0 827 Seymour Street, Kamloops and District Kamloops Kamloops, BC kamloopsefry.com 250 374 2119 Elizabeth Fry Society V2C 2H6 442 Leon Avenue, Ki-Low-Na -

3595 Chambly Road

3595 Chambly Road Longueuil, QC Retail Property For Lease RETAIL SPACE FOR LEASE IN LONGUEUIL Avison Young is proud to present this unique opportunity to Available Area 2,000 to 15,000 square feet lease 2,000 to 15,000 square feet of commercial space with wide frontage on Chambly Road in Longueuil, adjacent to Floor Ground floor the Saint-Hubert borough. Availability Immediate Thanks to its location on one of the busiest arteries in the area, the property benefits from exceptional visibility as well Parking 50 exterior spaces as easy accessibility. The premises represent a unique leasing opportunity for any retailer looking to establish a new location Asking Rent Contact broker on the South Shore of Montreal. Additional Rent Included in gross rent Avison Young Québec Inc., Commercial Real Estate Agency 1200 McGill College Avenue, Suite 2000 Montréal, Québec H3B 4G7 514.940.5330 | avisonyoung.com 3595 Chambly Road Longueuil, QC SIR-WILFRID-LAURIER BOULEVARD 116 1 3 5 6 4 8 2 7 9 10 3595 Chambly Road CHAMBLY ROAD12 13 11 14 15 16 VAUQUELIN BOULEVARDResidential Area CUVILLIER STREET Fonrouge Park NEIGHBOURHOOD 1 Montréal-Saint-Hubert-Longueuil Airport 9 Victory Gym 2 Longueuil Public Market 10 Corbeil Appliances 3 Olivier Ford 11 Honda 4 Place Julien-Lord 12 Dental and Orthodontic Centres 5 Giant Tiger 13 Rosie-Joseph Residence 6 Warehouse Club 14 Chartwell Villa Rive-Sud Residence 7 A&W 15 Carrosserie et Véhicules d’occasion Dealership 8 Ben & Florentine 16 Les Fontaines Residence Avison Young | 3595 Chambly Road 30 640 19 Boucherville Greater Montreal 25 Laval 3 2 20 440 Longueuil 15 132 40 3595 Chambly Road 116 1 720 Montréal Saint-Hubert 15 5 4 Brossard 8 20 6 20 7 10 30 La Prairie LOCATION 3595 Chambly Road is strategically located in proximity to 1 Promenades Saint-Bruno Mall Route 116 in Longueuil. -

Vividata Brands by Category

Brand List 1 Table of Contents Television 3-9 Radio/Audio 9-13 Internet 13 Websites/Apps 13-15 Digital Devices/Mobile Phone 15-16 Visit to Union Station, Yonge Dundas 16 Finance 16-20 Personal Care, Health & Beauty Aids 20-28 Cosmetics, Women’s Products 29-30 Automotive 31-35 Travel, Uber, NFL 36-39 Leisure, Restaurants, lotteries 39-41 Real Estate, Home Improvements 41-43 Apparel, Shopping, Retail 43-47 Home Electronics (Video Game Systems & Batteries) 47-48 Groceries 48-54 Candy, Snacks 54-59 Beverages 60-61 Alcohol 61-67 HH Products, Pets 67-70 Children’s Products 70 Note: ($) – These brands are available for analysis at an additional cost. 2 TELEVISION – “Paid” • Extreme Sports Service Provider “$” • Figure Skating • Bell TV • CFL Football-Regular Season • Bell Fibe • CFL Football-Playoffs • Bell Satellite TV • NFL Football-Regular Season • Cogeco • NFL Football-Playoffs • Eastlink • Golf • Rogers • Minor Hockey League • Shaw Cable • NHL Hockey-Regular Season • Shaw Direct • NHL Hockey-Playoffs • TELUS • Mixed Martial Arts • Videotron • Poker • Other (e.g. Netflix, CraveTV, etc.) • Rugby Online Viewing (TV/Video) “$” • Skiing/Ski-Jumping/Snowboarding • Crave TV • Soccer-European • Illico • Soccer-Major League • iTunes/Apple TV • Tennis • Netflix • Wrestling-Professional • TV/Video on Demand Binge Watching • YouTube TV Channels - English • Vimeo • ABC Spark TELEVISION – “Unpaid” • Action Sports Type Watched In Season • Animal Planet • Auto Racing-NASCAR Races • BBC Canada • Auto Racing-Formula 1 Races • BNN Business News Network • Auto -

DE MONT-ROYAL Habitable, 4 Chambres, 3 Salles De Bains Et Une Vous Êtes Entre Bonnes Mains! Salle D'eau Et Un Garage

S T E L A VENDRE: ATTEIGNEZ LE SOMMET! E 601 Av. Kinderlsey TMR STELE • MÉDIAS, COMMUNICATIONS ET RELATIONS PUBLIQUES INC. ANDREAS MINKOFSKI COURTIER IMMOBILIER 2 395 000$ Grande maison rénovée avec près de 3000 pc DE MONT-ROYAL habitable, 4 chambres, 3 salles de bains et une VOUS ÊTES ENTRE BONNES MAINS! salle d'eau et un garage. S 4 3+1 1+4 T www.stele-medias.com E L Au service de notre communauté E Votre JournalServing de Mont-Royal our community depuis 1998 courtier Number 1* broker at immobilier (514) 994-2741 STELE Médias Inc An independant weekly serving your Town RE/MAX du Cartier Town of Mont-Royal L’immobilier [email protected] (2015-2016-2017-2018-2019) nous habite! Groupe sutton immobilia • agence immobilière 21 OCTOBRE 2020 HEBDOMADAIRE ÉDITION 23.40 514-731-7575 TMR Council Oct 2020 QUEBEC’S SUBSIDIES MAKE UP FOR TMR’S COVID LOSSES, MAYOR SAYS IN REPORT MARTIN C. BARRY In a report on TMR’s financial situation during the town council webcast last Monday, Mayor Philippe Roy said TMR has lost $5.8 million since March when the COVID-19 pandemic started, while unforeseen COVID-19 expenses have cost TMR $400,000 so far. “Since mid-March 2020, the Town of Mount Royal has been dealing with the effects of COVID-19,” said Roy, adding that “the impact on the municipality’s finances is certain,” while revenues from building permits, fines, interest and registration fees from cultural and recreational programs “are far below” what had been budgeted. -

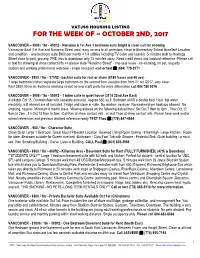

For the Week of ~ October 2Nd, 2017

VATJSS HOUSING LISTING FOR THE WEEK OF ~ OCTOBER 2ND, 2017 VANCOUVER – $900 / 1br - 450ft2 - Nanaimo & 1st Ave 1 bedroom suite bright & clean call for showing Vancouver East (1st Ave and Nanaimo Street area) easy access to all amenities. close to Elementary School Excellent Location and condition. - one bedroom suite $900 per month + 1/4 utilities including TV cable and laundry -5 minutes walk to Hastings Street close to park, grocery, PNE, bus to downtown only 15 minutes away. Need credit check and landlord reference -Please call or text for showing at show contact info >> please state "Nanaimo Street" - one year lease - no smoking, no pet, no party - student and working professional welcome - single occupant -call or text ☎ (604) 779-0171 VANCOUVER - $850 / 1br - 375ft2 - bachler suite for rent or share (6185 fraser and 46 ave) 1 large bedroom kitchen separate large bathroom on the second floor avalable from from 01 oct /2017. very clean Rent $850.00 inc bc bydro no smoking no pet no over night party for more information call 604 780 9516 VANCOUVER – $900 / 1br - 550ft2 - 1 bdrm suite in quiet house (3174 22nd Ave East) Available Oct.15. On main floor with separate entrance. Approx 550 sq.ft. Bedroom will fit a double bed. Heat, hot water, electricity, wifi internet are all included. Fridge and stove in suite. No washer, no dryer. No washer/dryer hookups allowed. No smoking, no pets. Minimum 6 month lease. Viewing allowed on the following dates/times: Sat.Oct.7 9am to 1pm , Thur.Oct.12 9am to 2pm , Fri.Oct.13 9am to 2pm -Call Kim at