Nature in the Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim and the “Frostfall” Ecomod

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development and Validation of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (Guess)

THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) A Dissertation by Mikki Hoang Phan Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2012 Bachelor of Arts, Wichita State University, 2008 Submitted to the Department of Psychology and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Mikki Phan All Rights Reserved THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a major in Psychology. _____________________________________ Barbara S. Chaparro, Committee Chair _____________________________________ Joseph Keebler, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jibo He, Committee Member _____________________________________ Darwin Dorr, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Member Accepted for the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences _____________________________________ Ronald Matson, Dean Accepted for the Graduate School _____________________________________ Abu S. Masud, Interim Dean iii DEDICATION To my parents for their love and support, and all that they have sacrificed so that my siblings and I can have a better future iv Video games open worlds. — Jon-Paul Dyson v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Althea Gibson once said, “No matter what accomplishments you make, somebody helped you.” Thus, completing this long and winding Ph.D. journey would not have been possible without a village of support and help. While words could not adequately sum up how thankful I am, I would like to start off by thanking my dissertation chair and advisor, Dr. -

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11, 2014 8:00 AM ET The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim and BioShock® Infinite; Borderlands® 2 and Dishonored™ bundles deliver supreme quality at an unprecedented price NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Feb. 11, 2014-- 2K and Bethesda Softworks® today announced that four of the most critically-acclaimed video games of their generation – The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim, BioShock® Infinite, Borderlands® 2, and Dishonored™ – are now available in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation®3 computer entertainment system, and Windows PC. ● The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim & BioShock Infinite Bundle combines two blockbusters from world-renowned developers Bethesda Game Studios and Irrational Games. ● The Borderlands 2 & Dishonored Bundle combines Gearbox Software’s fan favorite shooter-looter with Arkane Studio’s first- person action breakout hit. Critics agree that Skyrim, BioShock Infinite, Borderlands 2, and Dishonored are four of the most celebrated and influential games of all time. 2K and Bethesda Softworks(R) today announced that four of the most critically- ● Skyrim garnered more than 50 perfect review acclaimed video games of their generation - The Elder Scrolls(R) V: Skyrim, scores and more than 200 awards on its way BioShock(R) Infinite, Borderlands(R) 2, and Dishonored(TM) - are now available to a 94 overall rating**, earning praise from in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 some of the industry’s most influential and games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation(R)3 computer respected critics. -

Pdf (Accessed 2.10.14)

Notes 1 Introduction: Video Games and Storytelling 1. It must be noted that the term ‘Narratological’ is a rather loose application by the Ludologists and the implications of this are pointed out later in this chapter. 2. Roland Barthes states that the ‘infinity of the signifier refers not to some idea of the ineffable (the unnameable signified) but to that of a playing [ ...] theText is plural’. Source: Barthes, R., 1977. Image, Music, Text, in: Heath,S.(Tran.), Fontana Communications Series. Fontana, London. pp. 158–159. 3.In Gaming Globally: Production, Play, and Place (Huntemann and Aslinger, 2012),theeditors acknowledgethat ‘while gaming maybe global, gaming cultures and practices vary widely depending on the power and voice of var- ious stakeholders’ (p. 27). The paucity of games studies scholarship coming from some of the largest consumers of video games, such as South Korea, China and India, to name a few, is markedly noticeable. The lack of represen- tation of non-Western conceptions of play culture and storytelling traditions is similarly problematic. 4. Chapter 8 will engage with this issue in more detail. 5. ‘(W)reading’ is preferred over the more commonly used neologism ‘wread- ing’toemphasise the supplementarity of the reading and writingprocesses and also to differentiate it from earlier usage that might claim that the two processes are the same thing. 3 (W)Reading the Machinic Game-Narrative 6. For whichhe is criticisedby Hayles (see Chapter 2). 7. Landow respondstothis by rightly stating that Aarseth misreads his original comment where heclaims that ‘the reader whochooses among linksortakes advantage of Storyspace’s hypertext capabilities shares some of the power of theauthor’(Landow, p. -

Drafts April

ACTION ADVENTURE FIRST PERSON SHOOTER THIRD PERSON SHOOTER Star Wars: Jedi Fallen Dragon Quest Wolfenstein: Ace Combat 7: SU 81 Sea of Solitude Metro: Exodus 83 Anthem 61 The Darwin Project Order Builders II Youngblood Ancestors; The Shenmue 3 Devil May Cry 5 88 The Dark Pictures Halo: Infinite Far Cry New Dawn 74 Control The Division 2 83 Human Kind Odyssey Earth Defense Force: Skull and Bones Nioh 2 Skull and Bones The Sinking City Rage 2 Doom Eternal Left Alive 37 Iron Rain Mechwarrior 5: Mechwarrior 5: Remnant Rise From Dying Light 2 The Blackout Club Deep Rock Galactic Generation Zero 49 Gears 5 Mercenaries Mercenaries The Ashes FIGHTING SPORTS RACING STRATEGY Jump Force 58 Mortal Kombat 11 NBA 2K ‘20 NBA Live ‘20 Sonic Team Racing Trials Rising 80 Age of Empires 4 Wargroove 83 Total War Dead or Alive 6 75 Dirt Rally 2.0 83 GTR 3 Conan Unconquered Samurai Shodown NHL ‘20 Madden ‘20 Three Kingdoms Granblue Fantasy Shovel Knight: MLB The Show 19 85 PES 2020 Dangerous Driving Xenon Racer 57 Tropico 6 78 Re-Legion 52 Versus Showdown Them’s Fighting Pro Fishing Monster Energy The Grand Tour KILL la KILL - IF FIFA ‘20 - 73 48 Imperator Rome Phoenix Point Herds Simulator Supercross 2 Game RPG ACTION RPG INDIE & ARCADE GAMES (PICK 2) Indivisible Digimon Survive God Eater 3 73 Kingdom Hearts 3 85 UFO50 Streets of Rage 4 Jenny LeClue Tunche Away: Journey To Town Greedfall Biomutant Code Vein 61 Hyper Jam 74 Toe Jame & Earl:BitG 72 Sayonara Wild Hearts The Unexpected Wasteland 3 Torchlight: Frontiers The Outer Worlds The Surge 2 Moving Out Untitled -

Ubisoft to Co-Publish Oblivion™ on Playstation®3 and Playstation® Portable Systems in Europe and Australia

UBISOFT TO CO-PUBLISH OBLIVION™ ON PLAYSTATION®3 AND PLAYSTATION® PORTABLE SYSTEMS IN EUROPE AND AUSTRALIA Paris, FRANCE – September 28, 2006 – Today Ubisoft, one of the world’s largest video game publishers, announced that it has reached an agreement with Bethesda Softworks® to co-publish the blockbuster role-playing game The Elder Scrolls® IV: Oblivion™ on PLAYSTATION®3 and The Elder Scrolls® Travels: Oblivion™ for PlayStation®Portable (PSP™) systems in Europe and Australia. Developed by Bethesda Games Studios, Oblivion is the latest chapter in the epic and highly successful Elder Scrolls series and utilizes next- generation video game hardware to fully immerse the players into an experience unlike any other. Oblivion is scheduled to ship for the PLAYSTATION®3 European launch in March 2007 and Spring 2007 on PSP®. “We are pleased to partner with Besthesda Softworks to bring this landmark role-playing game to all PlayStation fans,” said Alain Corre EMEA Executive Director. “No doubt that this brand new version will continue the great Oblivion success story” The Elder Scrolls® IV: Oblivion has an average review score of 93.6%1 and has sold over 1.7 million units world-wide since its launch in March 2006. It has become a standard on Windows and the Xbox 360 TM entertainment system thanks to its graphics, outstanding freeform role- playing, and its hundreds of hours worth of gameplay. 1 Source : gamerankings.com About Ubisoft Ubisoft is a leading producer, publisher and distributor of interactive entertainment products worldwide and has grown considerably through its strong and diversified lineup of products and partnerships. -

Inside the Video Game Industry

Inside the Video Game Industry GameDevelopersTalkAbout theBusinessofPlay Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman Downloaded by [Pennsylvania State University] at 11:09 14 September 2017 First published by Routledge Th ird Avenue, New York, NY and by Routledge Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business © Taylor & Francis Th e right of Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman to be identifi ed as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections and of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act . All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice : Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identifi cation and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Names: Ruggill, Judd Ethan, editor. | McAllister, Ken S., – editor. | Nichols, Randall K., editor. | Kaufman, Ryan, editor. Title: Inside the video game industry : game developers talk about the business of play / edited by Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman. Description: New York : Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa Business, [] | Includes index. Identifi ers: LCCN | ISBN (hardback) | ISBN (pbk.) | ISBN (ebk) Subjects: LCSH: Video games industry. -

Loot Crate and Bethesda Softworks Announce Fallout® 4 Limited Edition Crate Exclusive Game-Related Collectibles Will Be Available November 2015

Loot Crate and Bethesda Softworks Announce Fallout® 4 Limited Edition Crate Exclusive Game-Related Collectibles Will Be Available November 2015 LOS ANGELES, CA -- (July 28th, 2015) -- Loot Crate, the monthly geek and gamer subscription service, today announced their partnership today with Bethesda Softworks® to create an exclusive, limited edition Fallout® 4 crate to be released in conjunction with the game’s worldwide launch on November 10, 2015 for the Xbox One, PlayStation® 4 computer entertainment system and PC. Bethesda Softworks exploded hearts everywhere when they officially announced Fallout 4 - the next generation of open-world gaming from the team at Bethesda Game Studios®. Following the game’s official announcement and its world premiere during Bethesda’s E3 Showcase, Bethesda Softworks and Loot Crate are teaming up to curate an official specialty crate full of Fallout goods. “We’re having a lot of fun working with Loot Crate on items for this limited edition crate,” said Pete Hines, VP of Marketing and PR at Bethesda Softworks. “The Fallout universe allows for so many possibilities – and we’re sure fans will be excited about what’s in store.” "We're honored to partner with the much-respected Bethesda and, together, determine what crate items would do justice to both Fallout and its fans," says Matthew Arevalo, co-founder and CXO of Loot Crate. "I'm excited that I can FINALLY tell people about this project, and I can't wait to see how the community reacts!" As is typical for a Loot Crate offering, the contents of the Fallout 4 limited edition crate will remain a mystery until they are delivered in November. -

Download Game Age Empires 2 Full Version Gratis Age of Empires 2 Free Download

download game age empires 2 full version gratis Age Of Empires 2 Free Download. Age Of Empires 2 Free Download Preview. Age Of Empires 2 Free Download: is a commended constant system computer game created by Ensemble Studios and distributed by Microsoft for home PCs in 1999. Created on the updated adaptation of the Genie Engine that controlled the first form of the Age of Empires in 1997, this continuation figured out how to develop pretty much every viewpoint and gain the standing of a standout amongst other RTS games, time. Click Below to Start Age Of Empires 2 Free Download. Set in the Middle Ages and with a capacity to move to more up to date verifiable periods like Dark Age, Feudal Age, Castle Age, and Imperial Age, the game offers players a mind boggling assortment of difficulties in the single-player crusade missions and an unfathomable assortment of strategic conflicts in smoothed out online modes. This included five verifiable single-player crusades, three extra single-player modes, and a completely highlighted multiplayer. Period of Empires II game had underlying help for thirteen playable human advancements, all including their extraordinary units (two for each development), visual style, and favored strategies for setting up fortresses and beating rivals. The center interactivity circle of the game followed the proven equation of overseeing developments of towns, gathering assets, preparing armed forces, and taking sound strategic actions to outmaneuver either PC controlled AI players or genuine adversaries situated at close by PCs by means of Ethernet associations or overall players through the Internet. -

Stubbs the Zombie: Rebel Without 21 Starship Troopers PC Continues to Set the Standard for Both Technology and Advancements in Gameplay

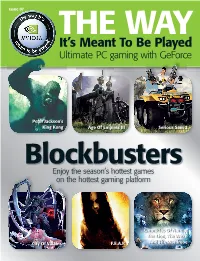

Issue 07 THE WAY It’s Meant To Be Played Peter Jackson’s King Kong Age Of Empires III Serious Sam 2 Blockbusters Enjoy the season’s hottest games on the hottest gaming platform Chronicles Of Narnia: The Lion, The Witch City Of Villains F.E.A.R And The Wardrobe NNVM07.p01usVM07.p01us 1 119/9/059/9/05 33:57:57:57:57 ppmm The way it’s meant to be played 3 6 7 8 Welcome Welcome to Issue 7 of The Way It’s Meant 12 13 to be Played, the magazine that showcases the very best of the latest PC games. All the 30 titles featured in this issue are participants in NVIDIA’s The Way It’s Meant To Be Played program, a campaign designed to deliver the best interactive entertainment experience. Development teams taking part in 14 19 the program are given access to NVIDIA’s hardware, with NVIDIA’s developer technology engineers on hand to help them get the very best graphics and effects into their new games. The games are then rigorously tested by NVIDIA for compatibility, stability and reliability to ensure that customers can buy any game with the TWIMTBP logo on the box and feel confident that the game will deliver the ultimate install- and-play experience when played with an Contents NVIDIA GeForce-based graphics card. Game developers today like to use 3 NVIDIA news 14 Chronicles Of Narnia: The Lion, Shader Model 3.0 technology for stunning, The Witch And The Wardrobe complex cinematic effects – a technology TWIMTBP games 15 Peter Jackson’s King Kong fully supported by all the latest NVIDIA 4 Vietcong 2 16 F.E.A.R. -

Age of Empires: Expandable Card Game the Age of Empires

Age Rules.qxd 10/13/00 9:42 AM Page 1 Age of Empires: Expandable Card Game A Journeyman Press Product Game design: Marcus D’Amelio and Ted Triebull Original Concept & Additional Design: David May Art Direction: David Aikins, Lynette Castator & Jonathan Queen Editing: Todd Breitenstein Game distributed and produced by: Journeyman Press 4590 Beech Street Cincinnati, Ohio, 45212 Artists: David Aikens, Andy Bennett, Brent Bowman, Matt Busch, Joe Corroney, Dave Groff, Joe Kovach, Lissanne Lake, Ron Miller, Tom Miller, Lee Moyer, Aric Nicholson, Steve Prescott, Jonathan Queen, Chris Seaman, R. Ward Shipman, Anthony Weiler. Special Thanks To: Brian Woodward, Adrienne Youngblood, Kathleen Thill, James Perry, Rachel Triebull, James McDaniel, Nancy Figatnur, Jordan Weisman, Mike ‘Tass’ Chapman, Beej Chapman, Rob Lowry, Rich Gain, James Bernard, Mike Webb, Stan Sord, Neale J. Carter, Jarred Saxman, Steven Curran , Joseph Rodriguez, Angela Chapman, all the folks at Ensemble Studios (for making an incredible game in the first place), and the folks over at Microsoft (for making the card game possible). The Age of Empires: Expandable card game is a game of conquest, enlightenment, and civilization advancement. Just as in the computer game, you are the leader of a civilization that has begun to rise after the fall of Rome. Only you can lead your people out of the Dark Ages and into their place in history. This highly strategic game has the feel of a historical game combined with the fast-paced and continuously changing atmosphere of an expandable card game. Do you have what it takes to crush your foes? Contents 1 Age Rules.qxd 10/13/00 9:42 AM Page 2 Each starter box has a 96-card deck, four Age The Ages Cards, which are used to keep track of what Age you The overall concept of the game involves advance- are in; a Civilization Card, which shows the bonuses ment through four ages, the Dark Age, the Feudal that your civilization has; one Booster Pack, which Age, the Castle Age, and the Imperial Age. -

10Th IAA FINALISTS ANNOUNCED

10th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards Finalists GAME TITLE PUBLISHER DEVELOPER CREDITS Outstanding Achievement in Animation ANIMATION DIRECTOR LEAD ANIMATOR Gears of War Microsoft Game Studios Epic Games Aaron Herzog & Jay Hosfelt Jerry O'Flaherty Daxter Sony Computer Entertainment ReadyatDawn Art Director: Ru Weerasuriya Jerome de Menou Lego Star Wars II: The Original Trilogy LucasArts Traveller's Tales Jeremy Pardon Jeremy Pardon Rayman Raving Rabbids Ubisoft Ubisoft Montpellier Patrick Bodard Patrick Bodard Fight Night Round 3 Electronic Arts EA Sports Alan Cruz Andy Konieczny Outstanding Achievement in Art Direction VISUAL ART DIRECTOR TECHNICAL ART DIRECTOR Gears of War Microsoft Game Studios Epic Games Jerry O'Flaherty Chris Perna Final Fantasy XII Square Enix Square Enix Akihiko Yoshida Hideo Minaba Call of Duty 3 Activison Treyarch Treyarch Treyarch Tom Clancy's Rainbow Six: Vegas Ubisoft Ubisoft Montreal Olivier Leonardi Jeffrey Giles Viva Piñata Microsoft Game Studios Rare Outstanding Achievement in Soundtrack MUSIC SUPERVISOR Guitar Hero 2 Activision/Red Octane Harmonix Eric Brosius SingStar Rocks! Sony Computer Entertainment SCE London Studio Alex Hackford & Sergio Pimentel FIFA 07 Electronic Arts Electronic Arts Canada Joe Nickolls Marc Ecko's Getting Up Atari The Collective Marc Ecko, Sean "Diddy" Combs Scarface Sierra Entertainment Radical Entertainment Sound Director: Rob Bridgett Outstanding Achievement in Original Music Composition COMPOSER Call of Duty 3 Activison Treyarch Joel Goldsmith LocoRoco Sony Computer -

Winning in Games

Sector: Technology Dave Novosel September 29 , 20 20 [email protected] Winning In Games ♦ Microsoft (MSFT), although apparently a much better match than Oracle, lost out on the bidding for TikTok. But it may have saved itself some headaches, given the political interference in that situation. After losing that opportunity, the company turned immediately and announced the acquisition of ZeniMax Media, the parent company of Bethesda Softworks. Bethesda develops and publishes video games, including The Elder Scrolls, Doom, and Fallout. The deal expands Microsoft’s game studios from 15 to 23, strengthening its position in the rapidly expanding gaming market. The timing is good as Microsoft is about to launch its eagerly awaited Xbox Series X and Series S in time for the holiday season. In addition, Microsoft bolsters its line-up to attract more users to its Xbox Game Pass. Microsoft is paying $7.5 billion in cash to acquire ZeniMax Media. ZeniMax is privately held, but speculation is that annual revenue was less than $1 billion, implying that EBITDA was less than $300 million. Therefore the deal could be viewed as quite expensive. But Microsoft has such tremendous financial flexibility that it really won’t have much of an impact on the credit profile. The company has close to $14 billion in cash and another $123 billion in short-term investments. In addition, the company generated more than $30 billion of free cash flow in the fiscal year that just ended June 30 th . ♦ Microsoft posted revenue of $143 billion last year, so the acquisition’s financial impact on operations is minimal.