Rodenticide Use in Rodent Management in the United States: an Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rattus Norvegicus Polymorphic For. Warfarin Resistance

Heredity (1979), 43(2), 239-246 RELATIVE FITNESS OF GENOTYPES IN A POPULATION OF RATTUS NORVEGICUS POLYMORPHIC FOR. WARFARIN RESISTANCE G. G. PARTRIDGE Department of Genetics, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 38X* Received11 .iii.79 SUMMARY Resistance to warfarin and an increased vitamin K requirement appear to be pleiotropic effects of the same allele (Rw 2).Ina natural population containing resistant individuals where the use of warfarin is discouraged the change in the frequency of resistance should reflect the relative fitnesses of the three possible genotypes. A large polymorphic population of rats was extensively poisoned with warfarin and the level of resistance monitored regularly for a period of 18 months after withdrawal of the poison. During this period the proportion of resistant animals in live-capture samples decreased significantly from approxi-. mately 80 per cent to 33 per cent. This decline is consistent with a hypothesis of reduced fitness of both RwZRw2andRw'Rw2 genotypes relative to Rw'Rw' under natural conditions. The relative fitnesses of these genotypes were calculated using an optimisation method based on least squares analysis. These estimates were: Rw2Rw2 (0.46), Rw'Rw2 (077) and Rw1Rw' (100). Homozygous resistant individuals were found in some of the samples, confirm- log that the Rw2 allele does not act as a recessive lethal, although it must be extremely disadvantageous. Some heterogeneity was observed in the proportion of resistant animals in samples taken from different areas of the farm building complex. This could reflect stochastic processes influencing the Rw2 allele frequency in small peripheral populations. 1. INTRODUCTION THE anticoagulant rodenticide warfarin was introduced into Britain in 1953 (Greaves, 1971). -

Pharmacokinetics of Anticoagulant Rodenticides in Target and Non-Target Organisms Katherine Horak U.S

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Plant Publications Health Inspection Service 2018 Pharmacokinetics of Anticoagulant Rodenticides in Target and Non-target Organisms Katherine Horak U.S. Department of Agriculture, [email protected] Penny M. Fisher Landcare Research Brian M. Hopkins Landcare Research Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc Part of the Life Sciences Commons Horak, Katherine; Fisher, Penny M.; and Hopkins, Brian M., "Pharmacokinetics of Anticoagulant Rodenticides in Target and Non- target Organisms" (2018). USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications. 2091. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc/2091 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Chapter 4 Pharmacokinetics of Anticoagulant Rodenticides in Target and Non-target Organisms Katherine E. Horak, Penny M. Fisher, and Brian Hopkins 1 Introduction The concentration of a compound at the site of action is a determinant of its toxicity. This principle is affected by a variety of factors including the chemical properties of the compound (pKa, lipophilicity, molecular size), receptor binding affinity, route of exposure, and physiological properties of the organism. Many compounds have to undergo chemical changes, biotransformation, into more toxic or less toxic forms. Because of all of these variables, predicting toxic effects and performing risk assess- ments of compounds based solely on dose are less accurate than those that include data on absorption, distribution, metabolism (biotransformation), and excretion of the compound. -

A California Without Rodenticides: Challenges for Commensal Rodent Management in the Future

Human–Wildlife Interactions 13(2):212–225, Fall 2019 • digitalcommons.usu.edu/hwi A California without rodenticides: challenges for commensal rodent management in the future Niamh Quinn, University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources, South Coast Research and Extension Center, Irvine, CA 92618, USA [email protected] Sylvia Kenmuir, BASF, 26 Davis Drive, Research Triangle Park, NC 27709, USA Laura Krueger, Orange County Mosquito and Vector Control District, Garden Grove, CA 92843, USA Abstract: Rodenticides are an essential tool in the integrated pest management of infestations of commensal rodents (Rattus norvegicus, R. rattus, and Mus musculus). With the introduction of Assembly Bill 1788, the California Ecosystems Protection Act of 2019, California is potentially facing a future with new restrictions on the use of anticoagulant rodenticides to manage commensal rodents in urban areas. Assembly Bill 1788 has been proposed specifically to protect predators from anticoagulant rodenticide poisoning and seeks to restrict the application of second-generation anticoagulant rodenticides (SGARs) for use in many urban and non-urban areas of California, USA. Exclusion and cultural practices, such as landscape management and sanitation (i.e., cleaning of property including but not limited to trash containment and removal, and drain sanitation), remain important and successful tools for managing rodent populations. However, increased exposure of wildlife to anticoagulant rodenticides has been detected California. Several animal species have been documented as having succumbed to rodenticide toxicosis. When rodents are killed by SGARs and consumed by predators, SGAR residues have been detected in the livers of predatory species. However, the effects of chronic, sublethal exposure to predators are not well understood. -

RRAC Guidelines on Anticoagulant Rodenticide Resistance Management Editor: Rodenticide Resistance Action Committee (RRAC) of Croplife International Aim

RRAC guidelines on Anticoagulant Rodenticide Resistance Management Editor: Rodenticide Resistance Action Committee (RRAC) of CropLife International Aim This document provides guidance to advisors, national authorities, professionals, practitioners and others on the nature of anticoagulant resistance in rodents, the identification of anticoagulant resistance, strategies for rodenticide application that will avoid the development of resistance and the management of resistance where it occurs. The Rodenticide Resistance Action Committee (RRAC) is a working group within the framework of CropLife International. Participating companies include: Bayer CropScience, BASF, LiphaTech S. A., PelGar, Rentokil Initial, Syngenta and Zapi. Senior technical specialists, with specific expertise in rodenticides, represent their companies on this committee. The RRAC is grateful to the following co-authors: Stefan Endepols, Alan Buckle, Charlie Eason, Hans-Joachim Pelz, Adrian Meyer, Philippe Berny, Kristof Baert and Colin Prescott. Photos provided by Stefan Endepols. Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 2. Classification and history of rodenticide compounds ..............................................................................................3 3. Mode of action of anticoagulant rodenticides, resistance mechanisms, and resistance mutations ......................................................................................................6 -

Appendix B. Brodifacoum Papers That Were Accepted for ECOTOX

Appendix B. Brodifacoum Papers that Were Accepted for ECOTOX Acceptable for ECOTOX and OPP 1. Abou El-Khear, R. K. (2005). Evaluation and Records of Rome Anticoagulant Rodenticides Against Wild Rats Under the Reclaimed Lands Conditions. Alexandria Sci. Exch. 26: 142-147. EcoReference No.: 153588 Chemical of Concern: BDF,CPC,DFM,PPCP,WFN; Habitat: T; Effect Codes: POP; Code: LITE EVAL CODED (BDF,CPC), NO SURVEY (PPCP,WFN). 2. Ahmad, M. S. and Munir, S. (1990). Comparative Evaluation of Three Anticoagulants Brodifacoum, Bromadialone and Flucoumafen Against Indian Gerbil, Tatera indica. Pak.J.Zool. 22: 421-426. EcoReference No.: 75417 Chemical of Concern: BDF,BDL; Habitat: T; Effect Codes: MOR,BEH; Rejection Code: LITE EVAL CODED(BDF,BDL). 3. Ahmad, N. and Parshad, V. R. (1991). Evaluation of Rodenticidal Baits in Fields of Sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum). Indian J.Agric.Sci. 61: 281-284. EcoReference No.: 75653 Chemical of Concern: ZnP,BDF,BDL; Habitat: T; Effect Codes: POP; Rejection Code: LITE EVAL CODED(ZnP,BDF,BDL). 4. Ahmad, N., SHEIKHER, C., and Guraya, S. S. (1989). Rodenticidal Baitings in Wheat Fields of the Garhwal Himalayas. Trop.Pest Manag. 35: 282-285. EcoReference No.: 75606 Chemical of Concern: ZnP,BDF,BDL; Habitat: T; Effect Codes: POP; Rejection Code: LITE EVAL CODED(ZnP,BDF,BDL). 5. Alterio, N., Brown, K., and Moller, H. (1997). Secondary Poisoning of Mustelids in a New Zealand Nothofagus Forest. J.Zool.(London) 243: 863-869. EcoReference No.: 75652 Chemical of Concern: BDF; Habitat: T; Effect Codes: POP,MOR; Rejection Code: LITE EVAL CODED(BDF). 6. Alterio, N. and Moller, H. -

Persistent Organic Pollutants

PERSISTENT ORGANIC POLLUTANTS An Assessment Report on: DDT-Aldrin-Dieldrin-Endrin-Chlordane Heptachlor-Hexachlorobenzene Mirex-Toxaphene Polychlorinated Biphenyls Dioxins and Furans Prepared by: L. Ritter, K.R. Solomon, J. Forget Canadian Network of Toxicology Centres 620 Gordon Street Guelph ON Canada and M. Stemeroff and C.O'Leary Deloitte and Touche Consulting Group 98 Macdonell St., Guelph ON Canada For: The International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS) within the framework of the Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals (IOMC) This report is produced for the International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS). The work is carried out within the framework of the Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals (IOMC). The report does not necessarily represent the decisions or the stated policy of the United Nations Environment Programme, the International Labour Organisation, or the World Health Organization. The International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS) is a joint venture of the United Nations Environment Programme, the International Labour Organisation, and the World Health Organization. The main objective of the IPCS is to carry out and disseminate evaluations of the effects of chemicals on human health and the quality of the environment. Supporting activities include the development of epidemiological, experimental laboratory, and risk-assessment methods that could produce internationally comparable results, and the development of human resources in the field of chemical safety. Other activities carried out by the IPCS include the development of know-how for coping with chemical accidents, strengthening capabilities for prevention of an response to chemical accidents and their follow-up, coordination of laboratory testing and epidemiological studies, and promotion of research on the mechanisms of the biological action of chemicals. -

Additional Mitigation Measures for Rodenticides

Questions and Answers – Additional Mitigation Measures for Rodenticides About the Evaluation of Rodenticides 1. What are rodenticides? Rodenticides are pest control products registered for controlling mice, rats and other rodents that pose threats to public health, critical habitats, native plants and animals, crops, and food supplies. 2. Why did Health Canada re-evaluate rodenticides? As required under the Pest Control Product Act, Health Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA) conducts re-evaluations of older pesticides to ensure they meet modern health and safety standards. As scientific knowledge evolves and new information becomes available, the PMRA requires that registered pesticides be re-evaluated according to modern risk assessment approaches. The PMRA re-evaluated six rodenticides (brodifacoum, bromadiolone, chlorophacinone, diphacinone, warfarin and zinc phosphide) and published Re-evaluation Decision Documents (RRD2006-11 and RVD2007-01) in 2006 and 2007, respectively. The public was consulted prior to finalizing these decision documents (PACR2004-27 and PACR2006-08). 3. Why are additional mitigation measures required following re-evaluation? In 2010, the PMRA required additional protective measures for several rodenticides containing the following active ingredients: brodifacoum, bromadiolone, bromethalin, chlorophacinone, diphacinone, difethialone, warfarin and zinc phosphide, as part of an overall risk-reduction strategy for rodenticides in Canada. The name of the active ingredient contained in a rodenticide product is listed on the product label under “guarantee”. Rodenticides are highly acutely toxic compounds, and can be used in residential and agricultural settings. Additional protective measures are warranted in order to prevent exposure of children, pets and non-target wildlife to these chemicals. Manufacturers have until December 31, 2012 to have new labelling in place. -

Defending Nature Against Rodenticides

Defending Nature Against Rodenticides LAW 391D Topics in Environmental Law Green Rights & Warrior Lawyers Marie Turcott December 18, 2019 Page 12 I. INTRODUCTION: RATS, RODENTICIDES, AND RIGHTS OF NATURE .................... 2 II. THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR PESTICIDE REGULATION IN CANADA ............ 5 A. Federal Regulations ............................................................................................................................ 6 1. Developments in Federal Regulation of Rodenticides ...................................................................... 8 B. Provincial Regulation ....................................................................................................................... 10 C. Municipal Role .................................................................................................................................. 13 III. THE USE OF SECOND-GENERATION ANTICOAGULANT RODENTICIDES IS INCONSISTENT WITH THE CURRENT REGULATORY FRAMEWORK .................... 14 A. There is Reasonable Certainty that Harm Results from SGAR Use ........................................... 16 1. Risks to Nature: Wildlife and the Environment .............................................................................. 16 i. Direct poisoning of non-target primary consumers .................................................................................... 16 ii. Indirect poisoning of secondary consumer predator and scavenger species .............................................. 18 iii. Poisoning of the environment -

The Use of Sodium Cyanide in Wildlife Damage Management

Human Health and Ecological Risk Assessment for the Use of Wildlife Damage Management Methods by USDA-APHIS-Wildlife Services Chapter VII THE USE OF SODIUM CYANIDE IN WILDLIFE DAMAGE MANAGEMENT May 2017 Peer Reviewed Final October 2019 THE USE OF SODIUM CYANIDE IN WILDLIFE DAMAGE MANAGEMENT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY USDA-APHIS Wildlife Services (WS) uses sodium cyanide (NaCN) to manage coyotes, red foxes, gray foxes, arctic foxes, and wild dogs that prey upon livestock, poultry, and federally designated threatened and endangered species or animals that are vectors of disease. This human health and ecological risk assessment is an evaluation of the risks to human health, nontarget animals, and the environment from NaCN use by WS. WS uses the M-44, the name for the ejector device that delivers a single dose NaCN from a capsule, to target canids. The M-44 is spring-activated and is actuated when an animal pulls up on the capsule holder; a plunger propelled by the spring breaks through a capsule with dry NaCN to deliver the contents into the mouth of an animal. The WS applicator baits the M-44 capsule holder sides to attract target canids. Sodium cyanide reacts rapidly with moisture in the mouth or mucus membranes of the nose and eyes to form hydrogen cyanide (HCN), a toxicant. One NaCN capsule contains enough cyanide to be lethal to animals through oral contact, inhalation contact, and moist dermal pathway contact. WS annually averaged the known take of 13,959 target canids and 362 nontarget species with NaCN between FY11 and FY15, recording 1,548,000 Method Nights with M-44s in 17 States. -

Reference Guide to Non-Combustion Technologies for Remediation of Persistent Organic Pollutants in Soil, Second Edition – 2010

Reference Guide to Non-combustion TechnologiesTechnologies for Remediation of Persistent Organic PollutantsPollutants in Soil, SecondS Edition - 2010 ts B an ii ta oa llu ac ll cc o u P m iic u n lla a t g tii rr o O n O tt g a yc llii n n ll c y attii on n e na orra d tt sso ap a ev ss e d B ii ss nd ee a ss udd nn ii r iitt u tiioo oo r tt siit HighHiHig latitudes e ll a a os m e -- po iidd ep DepositionDDe > evaporation PP e a M dd a ff ff o gg o oo nn t r t ii ss r High mobility oo High mobility ff ii ee pp ss cc cc ee nn aa gg aa rr Relatively high mobility rr Long-range Relatively high mobility n t Long-range n t t t aa uu i r cc i r i oceanic i oceanic o - - o rr o o gg ee transport Low mobility n transport n n n h h S o S o p p L L s s o o m m m m m m m m t t t t t t t t t a a a a a a Low latitudes t t Deposition > evaporation c Deposition > evaporation c ee ff ff ee ”” gg iinn p pp op sh as Grr ll ““G a iic T m h e e h n e C iio rm ll-C tt a a a ll iic ad ys ra h eg P De B iiore ogy med hnoll diiatiion Phytotech RR eemme giieess eddiiaattiioonn TTeecchhnnoolloog Solid Waste EPA 542-R-09-007 and Emergency Response September 2010 (5203P) www.clu-in.org/POPs Reference Guide to Non-combustion Technologies for Remediation of Persistent Organic Pollutants in Soil, Second Edition – 2010 Internet Address (URL) http://www.epa.gov Recycled/Recyclable. -

Managing Pesticide Poisoning Risk and Understanding the Signs and Symptoms Clyde L

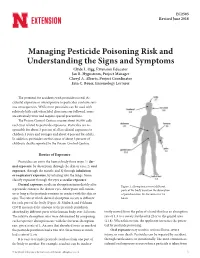

EC2505 Revised June 2018 Managing Pesticide Poisoning Risk and Understanding the Signs and Symptoms Clyde L. Ogg, Extension Educator Jan R. Hygnstrom, Project Manager Cheryl A. Alberts, Project Coordinator Erin C. Bauer, Entomology Lecturer The potential for accidents with pesticides is real. Ac- cidental exposure or overexposure to pesticides can have seri- ous consequences. While most pesticides can be used with relatively little risk when label directions are followed, some are extremely toxic and require special precautions. The Poison Control Centers receive about 90,000 calls each year related to pesticide exposures. Pesticides are re- sponsible for about 3 percent of all accidental exposures to children 5 years and younger and about 4 percent for adults. In addition, pesticides are the cause of about 3 percent of children’s deaths reported to the Poison Control Centers. Routes of Exposure Pesticides can enter the human body three ways: 1) der- mal exposure, by absorption through the skin or eyes; 2) oral exposure, through the mouth; and 3) through inhalation or respiratory exposure, by inhaling into the lungs. Some classify exposure through the eyes as ocular exposure. Dermal exposure results in absorption immediately after Figure 1. Absorption rates of different a pesticide contacts the skin or eyes. Absorption will contin- parts of the body based on the absorption ue as long as the pesticide remains in contact with the skin or of parathion into the forearm over 24 eyes. The rate at which dermal absorption occurs is different hours. for each part of the body (Figure 1). Maiback and Feldman (1974) measured the amount of the pesticide parathion absorbed by different parts of the human body over 24 hours. -

Rodenticides Labeled for Use to Control Meadow Voles and Pocket Gophers Updated June 13, 2016 MEADOW VOLE PRODUCTS

Rodenticides Labeled for Use to Control Meadow Voles and Pocket Gophers Updated June 13, 2016 ALWAYS read and follow the instructions printed on the pesticide label. The pesticides listed in these tables are currently registered with Idaho State Department of Agriculture. Pesticide labels change frequently and may have changed since this was written, therefore, check the current label to be sure it is registered for use. Products that are labeled as “Restricted Use” require an Idaho Pesticide Applicators License to purchase and apply. “General Use” products can be purchased and used by the general public 18 years and older. “General Use” products can be found in a variety of retail businesses, such as home improvement stores, farm stores, retail greenhouse businesses, and grocery stores. ATTENTION: If the product label lists any “commensal rodents” (Norway rat, roof rat, or house mouse), labels will have specific directions for use and location of bait stations, and product quantity allowed. Some, not all, of the products listed on these tables have commensal rodents listed on the labels. Be sure to thoroughly read and follow all label directions. MEADOW VOLE PRODUCTS GENERAL USE PESTICIDES—MEADOW VOLES THESE PRODUCTS ARE FOR HOMEOWNER/CONSUMER USE. Rodenticide Common Trade Restricted Rodenticide Consumer Labeled Uses/Comments Active Ingredient Names Use Pesticide Type Use Scoot Squirrel, Miller Hot Sauce Animal Biopesticide Spray on ornamentals, hay bales, vegetable crops. Do not use Capsaicin NO YES Repellent, Repellex spray, tablets indoors. Place tablet type formulations in water and apply to soil. Systemic tablets Mole Go Granules, Natural Use as a repellent around structures and plants.