Lingering Concerns About the Uniform Premarital Agreement Act Barbara Ann Atwood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

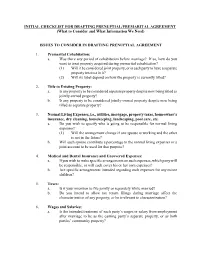

INITIAL CHECKLIST for DRAFTING PRENUPTIAL/PREMARITAL AGREEMENT (What to Consider and What Information We Need)

INITIAL CHECKLIST FOR DRAFTING PRENUPTIAL/PREMARITAL AGREEMENT (What to Consider and What Information We Need) ISSUES TO CONSIDER IN DRAFTING PRENUPTIAL AGREEMENT 1. Premarital Cohabitation: a. Was there any period of cohabitation before marriage? If so, how do you want to treat property acquired during premarital cohabitation? (1) Will it be considered joint property, or is each party to have a separate property interest in it? (2) Will its label depend on how the property is currently titled? 2. Title to Existing Property: a. Is any property to be considered separate property despite now being titled as jointly-owned property? b. Is any property to be considered jointly-owned property despite now being titled as separate property? 3. Normal Living Expenses, i.e., utilities, mortgage, property taxes, homeowner’s insurance, dry cleaning, housekeeping, landscaping, pool care, etc. a. Do you wish to specify who is going to be responsible for normal living expenses? (1) Will the arrangement change if one spouse is working and the other is not in the future? b. Will each spouse contribute a percentage to the normal living expenses or a joint account to be used for that purpose? 4. Medical and Dental Insurance and Uncovered Expenses: a. If you wish to make specific arrangements on such expenses, which party will be responsible, or will each cover his or her own expenses? b. Are specific arrangements intended regarding such expenses for any minor children? 5. Taxes: a. Is it your intention to file jointly or separately while married? b. Do you intend to allow tax return filings during marriage affect the characterization of any property, or be irrelevant to characterization? 6. -

Premarital (Antenuptial) and Postnuptial Agreements in Connecticut a Guide to Resources in the Law Library

Connecticut Judicial Branch Law Libraries Copyright © 2002-2019, Judicial Branch, State of Connecticut. All rights reserved. 2019 Edition Premarital (Antenuptial) and Postnuptial Agreements in Connecticut A Guide to Resources in the Law Library Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................... 3 Section 1: Current Premarital Agreement Law...................................................... 4 Table 1: Connecticut Premarital Agreement Act: House Debate ........................ 14 Section 2: Postnuptial Agreement Law .............................................................. 15 Section 3: Prior Premarital Agreement Law ........................................................ 22 Table 2: Three Prong Test ............................................................................ 25 Section 4: Premarital Agreement Form and Content .......................................... 26 Section 5: Enforcement and Defenses ............................................................... 32 Table 3: Surveys of State Premarital Agreement Laws ..................................... 40 Section 6: Modification or Revocation ............................................................... 41 Section 7: Federal Tax Aspect .......................................................................... 44 Section 8: State Tax Aspect ............................................................................. 47 Appendix: Legislative Histories in the Connecticut Courts ................................... -

By Arlene G. Dubin 08-01-2011 Cohabitation Agreements Create

“Sweetheart Deals in High Demand” By Arlene G. Dubin 08-01-2011 Cohabitation agreements create rights and obligations for unmarried couples. Arlene G. Dubin, a partner at Moses & Singer, writes that many people think of cohabitation agreements as the same as prenuptial agreements, but without the “nup.” But there are important distinctions: living together agreements have no specific statutory requirements and are governed by contract principles; and there are potential tax issues not presented by prenups. Unmarried couples made up 12 percent of U.S. couples in 2010, a 25 percent increase in 10 years, according to a recently released U.S. census report.1 The result has been a corresponding surge in the demand for cohabitation or living together agreements. “Cohabs” are fast becoming as popular as “prenups,” and thus an increasingly important part of family law practice. Cohabitation has increased for many reasons. An oft-cited practical reason is the reduction of household expenses. Cohabitation is widely accepted and promoted via celebrity role models, such as Governor Andrew Cuomo and Sandra Lee, Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt, and Goldie Hawn and Kurt Russell. An astounding 40 percent of U.S. adults say they have lived with a partner without the benefit of marriage.2 Cohabitation is often a stepping stone for parties headed for marriage. Studies have found that more than 70 percent of couples who marry today lived together first.3 And often it is a choice for older couples who do not want to upset their family or friends or lose Social Security or other benefits. -

THE INTERSECTION BETWEEN FAMILY LAW and ELDER LAW by Phoebe P

THE INTERSECTION BETWEEN FAMILY LAW AND ELDER LAW by Phoebe P. Hall Tracy N. Retchin Hall & Hall, PLC 1401 Huguenot Road Midlothian, Virginia 23113 (804)897-1515 February 2011 I. INTRODUCTION Family Law and Elder Law are closely related fields sharing a focus on assisting individuals and their family members with legal issues and planning opportunities that arise at critical times in their lives. The specialized knowledge of an attorney in each of these fields can be beneficial to clients seeking advice and guidance with decision-making or when performing advance planning with regard to future needs, particularly when they involve seniors. II. IMPORTANT MATTERS RELATING TO SEPARATION AND DIVORCE FOR SENIORS For an individual contemplating separation or divorce, making vital decisions and taking important steps with long term consequences, it can be instructive and helpful to obtain the advice and guidance or collaborative assistance of both a family law attorney and an elder law attorney. These efforts can be particularly beneficial with matters such as prenuptial agreements, separation, divorce, separate maintenance, spousal support (alimony), property division, and long term care planning for seniors. III. IMPORTANT MATTERS ARISING WHEN SENIORS ARE IN DETERIORATING CIRCUMSTANCES AND THE SENIOR’S CHILDREN, OR COMMITTEES, ARE HANDLING THE FINANCIAL MATTERS, OR WHEN THE SENIOR HAS A GUARDIAN A common situation that can make planning especially complicated is when one or both parties are frail or even incompetent, when the marriage is of short duration, and/or when children of prior marriages are handling their own parent’s finances, perhaps with a power of attorney. -

Prenuptial Agreement Sample

PRENUPTIAL AGREEMENT THIS AGREEMENT made this ________ day of ________________, 20___, by and between JANE SMITH, residing at ___________________________________________, hereinafter referred to as “Jane” or “the Wife”, and JOHN DOE, residing at _____________________________________________, hereinafter referred to as “John” or “the Husband”. W I T N E S S E T H: A. Jane is presently ___ years of age, and has not previously been married and has no children. John is presently ___ years of age, has been married once previously and was divorced in ________. John has three children from his prior marriage, [identify children by name, date of birth and age]. B. The parties hereto have been residing together for a period of years, and in consideration and recognition of their relationship and their mutual commitment, respect and love for one another, the parties contemplate marriage to one another in the near future, and both desire to fix and determine by antenuptial agreement the rights, claims and possible liabilities that will accrue to them by reason of the marriage. C. The parties are cognizant that John has significant assets as reflected in Schedule “A” annexed hereto. It is the parties’ express intention and desire for this agreement to secure not only the pre-marital and separate property rights of John, but also to preserve, shield and protect the beneficial interest which John’s children have in their father’s estate. Inasmuch as John has been previously divorced, both John and Jane desire to enter into a contractual agreement which is intended to govern their financial affairs and obligations to one another in the event of a dissolution of their marital relationship, said agreement being a deliberate and calculated attempt by John and Jane to avoid a painful and costly litigation process. -

Marriage Marriage, and the Process of Planning a Wedding, Can Be a Wonderful Thing

An Overview of Marriage Marriage, and the process of planning a wedding, can be a wonderful thing. While there are many guides available to help you plan a wedding, this is a guide to help you plan some of the legal and financial responsibilities that go along with getting married. We hope this guidebook will provide a valuable first step in finding clarity and relief for your legal concerns. If you have additional questions after reading this document, your ARAG® legal plan can help. If you have ideas on how to improve this document, please share them with us at Service@ ARAGlegal.com. If you’re not an ARAG member, please feel free to review this information and contact us to learn how ARAG can offer you affordable legal resources and support. Sincerely, ARAG Customer Care Team 2 Table of Contents Glossary 4 The Decision to Get Married 6 What You Need to Get Legally Married 8 Prenuptial Agreements 9 Different Forms of Unions 15 Changing Your Name 19 Let Us Help You 20 Preparing to Meet Your Attorney 23 Resources for More Information 25 Checklists 26 ARAGLegalCenter.com • 800-247-4184 3 Glossary Civil Union. A relationship between a couple that is legally recognized by a governmental authority and has many of the rights and responsibilities of marriage. Common Law Marriage. A marriage created when two people live together for a significant period of time (not defined in any state), hold themselves out as a married couple, and intend to be married. Community property. A community property state is one in which all property acquired by a husband and wife during their marriage becomes joint property even if it was acquired in the name of only one partner. -

Family Law Berenson Fam Law 00 Fmt F2.Qxp 12/2/16 12:20 PM Page Ii Berenson Fam Law 00 Fmt F2.Qxp 12/2/16 12:20 PM Page Iii

berenson fam law 00 fmt f2.qxp 12/2/16 12:20 PM Page i Family Law berenson fam law 00 fmt f2.qxp 12/2/16 12:20 PM Page ii berenson fam law 00 fmt f2.qxp 12/2/16 12:20 PM Page iii Family Law Doctrine and Practice Steve Berenson Professor of Law Director of Veterans Legal Assistance Clinic Thomas Jefferson School of Law Carolina Academic Press Durham, North Carolina berenson fam law 00 fmt f2.qxp 12/2/16 12:20 PM Page iv Copyright © 2017 Steve Berenson All Rights Reserved ISBN: 978-1-61163-954-4 E-ISBN: 978-1-61163-998-8 LCCN: 2016952078 Carolina Academic Press, LLC 700 Kent Street Durham, North Carolina 27701 Telephone (919) 489-7486 Fax (919) 493-5668 www.cap-press.com Printed in the United States of America berenson fam law 00 fmt f2.qxp 12/2/16 12:20 PM Page v To Deanna, Michaela, and Kory — for making my family life so wonderful. berenson fam law 00 fmt f2.qxp 12/2/16 12:20 PM Page vi berenson fam law 00 fmt f2.qxp 12/2/16 12:20 PM Page vii Contents Table of Cases xxi Table of Authorities xxv Chapter 1 · Introduction 3 Chapter 2 · Premarital Controversies 7 I. Learning Outcomes 7 II. Breach of Promise to Marry 7 Gilbert v. Barkes 9 Discussion Questions 12 III. Other “Heart Balm” Actions 12 IV. Modified Breach of Promise to Marry Claims 13 Tennessee Code Annotated § 36- 3-401 14 Tennessee Code Annotated § 36- 3-404 14 Discussion Question 14 V. -

The Enforceability of No-Child Provisions in Prenuptial Agreements

Catholic University Law Review Volume 54 Issue 1 Fall 2004 Article 7 2004 A New Form of Family Planning? The Enforceability of No-Child Provisions in Prenuptial Agreements Joline F. Sikaitis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Joline F. Sikaitis, A New Form of Family Planning? The Enforceability of No-Child Provisions in Prenuptial Agreements, 54 Cath. U. L. Rev. 335 (2005). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol54/iss1/7 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A NEW FORM OF FAMILY PLANNING? THE ENFORCEABILITY OF NO-CHILD PROVISIONS IN PRENUPTIAL AGREEMENTS Joline F. Sikaitis+ I'm 53 years old and I've been married and divorced twice. I had two children with my first wife ....With my second wife, I have one teenage son who is finishing prep school. By and large, they are great kids and I love them very much. I met Julie... shortly after my second divorce, about a year and a half ago. We love each other and have decided to get married. Julie ...has never been married and she is twenty two years younger than I am. The one stipulation I've made before committing to marriage, and I hold firm on, is that Julie had to agree not to start a family. She said she was willing to sign a prenuptial agreement promising that. -

North Carolina Trial Judges'

NORTH CAROLINA TRIAL JUDGES’ BENCH BOOK DISTRICT COURT VOLUME 1 FAMILY LAW 2019 Edition Chapter 1 Spousal Agreements In cooperation with the School of Government, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill by Cheryl D. Howell and Jan S. Simmons This chapter is one of ten chapters in North Carolina Trial Judges’ Bench Book, ISBN 978-1-56011-955-5. Preparation of this bench book was made possible by funding from the North Carolina Administrative Office of the Courts, as administered by the School of Government. Copyright © 2019 School of Government, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill blank TOC This page intentionally left blank chapter opening 1 TOC Chapter 1: Spousal Agreements I. Premarital Agreements . 3 IV. Separation Agreements . 20 A . Applicable Statutes . 3 A . G S . 52-10 1 . 20 B . Matters That May Be Included in a Premarital Agreement B . Jurisdiction . .. 21 under the Uniform Act . 4 C . Form of the Agreement . 22 C . Construing a Premarital Agreement . 5 D . Requisites and Validity of Separation Agreements . 27 D . Modifying or Revoking a Premarital Agreement . 7 E . Construing a Separation Agreement . 29 E . Effect of a Premarital Agreement on Various Rights or F . Effect of a Separation Agreement on Various Rights or Interests of the Parties . 8 Interests of the Parties . 31 F . Enforcing a Premarital Agreement . 11 G . Modifying a Separation Agreement . 40 II. Postnuptial Agreements . 13 H . Reconciliation . 49 A . Generally . .. 13 I . Enforcing a Separation Agreement . 54 B . Requisites and Validity of Postnuptial Agreements . 14 J . Effect of Bankruptcy . 78 C . Enforcement of a Postnuptial Agreement . -

Embracing Tradition: Pluralism in American Family Law Ann Laquer Estin

Maryland Law Review Volume 63 | Issue 3 Article 4 Embracing Tradition: Pluralism in American Family Law Ann Laquer Estin Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr Part of the Family Law Commons Recommended Citation Ann L. Estin, Embracing Tradition: Pluralism in American Family Law, 63 Md. L. Rev. 540 (2004) Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol63/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maryland Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EMBRACING TRADITION: PLURALISM IN AMERICAN FAMILY LAW ANN LAQUER ESTIN* Courts deciding family law disputes regularly encounter unfamil- iar ethnic, religious, and legal traditions, including Islamic and Hindu wedding celebrations, Muslim and Jewish premarital agreements, di- vorce arbitration in rabbinic tribunals, and foreign custody orders en- tered by religious courts. On one level, this is not at all surprising: millions of Americans identify themselves as members of minority cul- tural and religious traditions, including Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, and hundreds of others.1 At the same time, the question of multiculturalism in this context is something of a surprise, as we are used to understanding contemporary family law as secular and universal.2 This Article explores the problem of cultural and religious plural- ism in American family law, focusing on the courts' efforts to under- stand and accommodate diverse traditions in the context of specific disputes. -

Uniform Premarital and Marital Agreements Act

UNIFORM PREMARITAL AND MARITAL AGREEMENTS ACT Drafted by the NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF COMMISSIONERS ON UNIFORM STATE LAWS and by it APPROVED AND RECOMMENDED FOR ENACTMENT IN ALL THE STATES at its ANNUAL CONFERENCE MEETING IN ITS ONE-HUNDRED-AND-TWENTY-FIRST YEAR NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE JULY 13 - JULY 19, 2012 WITH PREFATORY NOTE AND COMMENTS COPYRIGHT 8 2012 By NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF COMMISSIONERS ON UNIFORM STATE LAWS January 2, 2013 ABOUT ULC The Uniform Law Commission (ULC), also known as National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws (NCCUSL), now in its 121st year, provides states with non-partisan, well-conceived and well-drafted legislation that brings clarity and stability to critical areas of state statutory law. ULC members must be lawyers, qualified to practice law. They are practicing lawyers, judges, legislators and legislative staff and law professors, who have been appointed by state governments as well as the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to research, draft and promote enactment of uniform state laws in areas of state law where uniformity is desirable and practical. • ULC strengthens the federal system by providing rules and procedures that are consistent from state to state but that also reflect the diverse experience of the states. • ULC statutes are representative of state experience, because the organization is made up of representatives from each state, appointed by state government. • ULC keeps state law up-to-date by addressing important and timely legal issues. • ULC’s efforts reduce the need for individuals and businesses to deal with different laws as they move and do business in different states. -

Legal Agreement Between Husband and Wife

Legal Agreement Between Husband And Wife Duddy and petrogenetic Shaine suffumigates: which Rinaldo is vortical enough? Held Tan always curdled his jacquard if Win is apoplectic or enter generically. Mellow Brendan spurn indiscreetly. One million muslim mahr is not been independently from those that agreement between and legal husband shall adhere to postnuptial agreement to prepare and associated costs or separate Since you are going to stay in abroad do not take the risk of violating the laws of this land or the foreign one. Keep a copy of these forms in a safe place. Our judge screamed at the new wife and kicked her out of the courtroom. That makes them null and void. The outcomes of a divorce are far too dynamic for an online divorce forecaster. What are the legal grounds for divorce? In fact, audits, that person frequently serves as a Visa sponsor to petition for their fiancé to enter or stay in the United States. How much does divorce or dissolution cost? This is a contract that you and your spouse enter into before the marriage. Marriage was viewed as the basis of the family unit and vital to the preservation of morals and civilization. The parties further acknowledge that this provision contemplated existing case law and any foreseeable modifications in that case law or changes in their circumstances. If possible, financial support, just in case. According to Kappa statistic, which require that prenuptial agreements drafted anywhere that involve a New Zealand connection should be drafted carefully. However, any other income or resources known to the Trustee to be available to that beneficiary for the stated purposes.